Anat Cell Biol.

2024 Sep;57(3):431-445. 10.5115/acb.24.034.

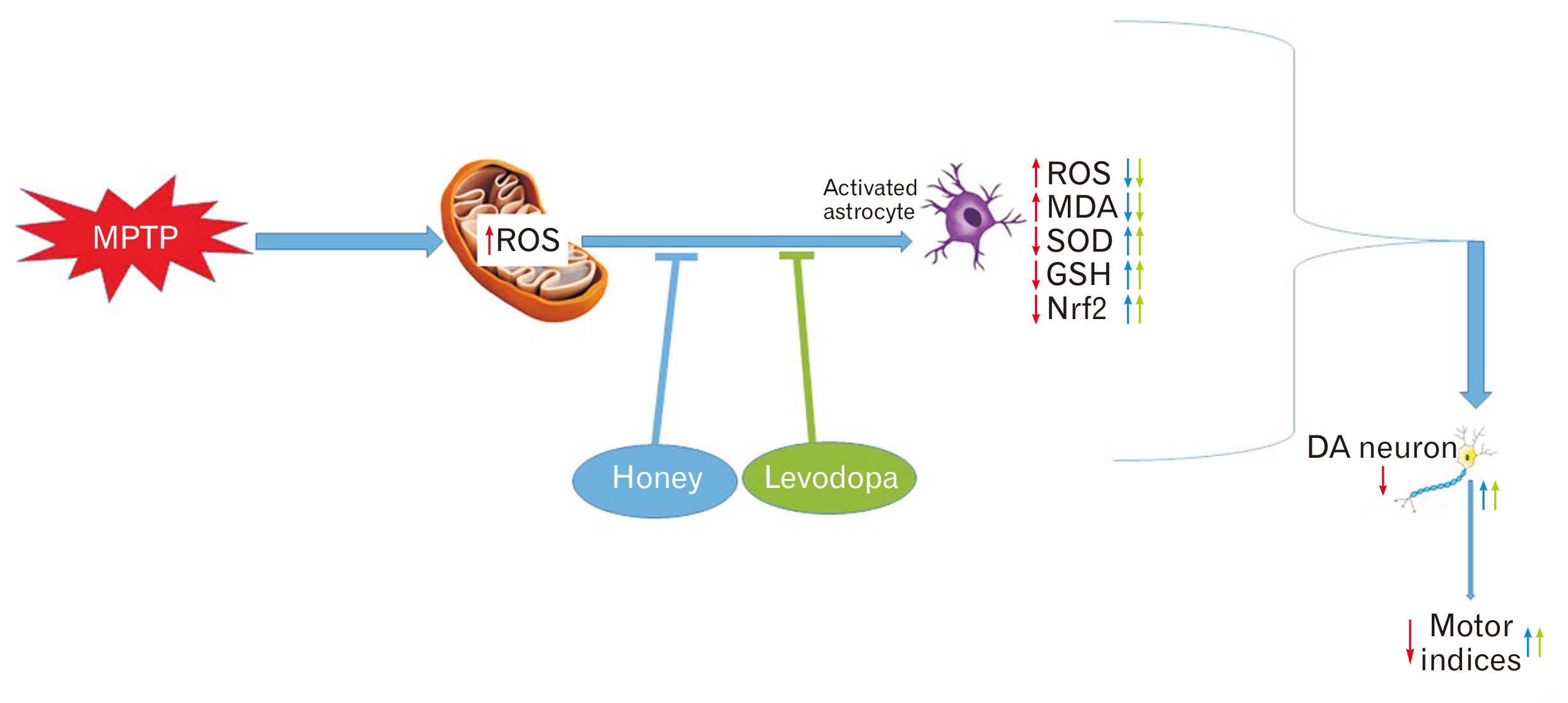

Honey and levodopa comparably preserved substantia nigra pars compacta neurons through the modulation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 signaling pathway in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridineinduced Parkinson’s disease model

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

- 2Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria

- 3Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

- 4Department of Chemical Pathology, Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

- KMID: 2559762

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5115/acb.24.034

Abstract

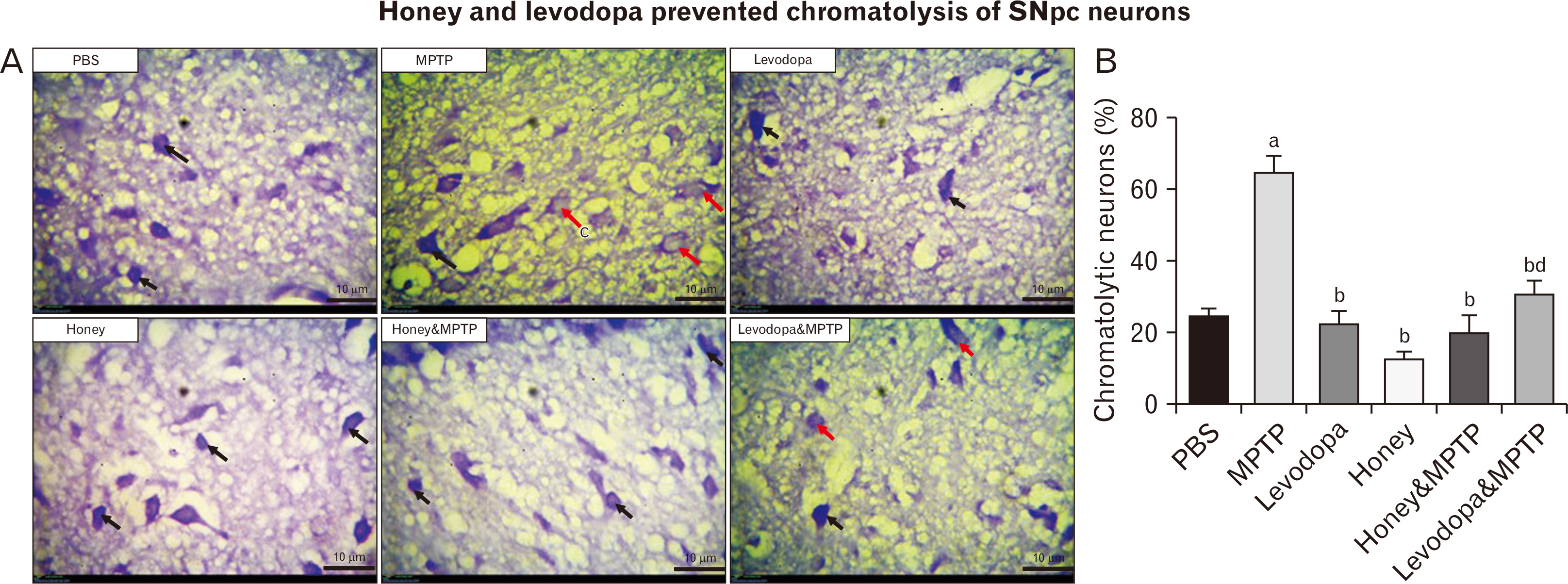

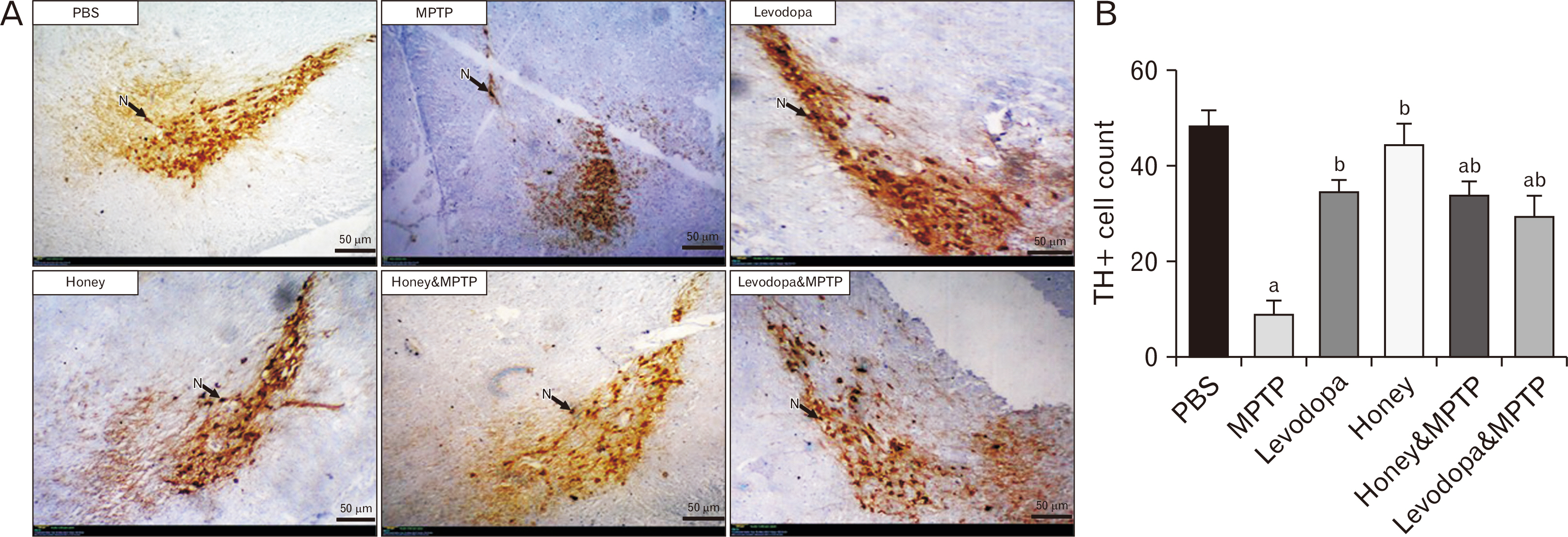

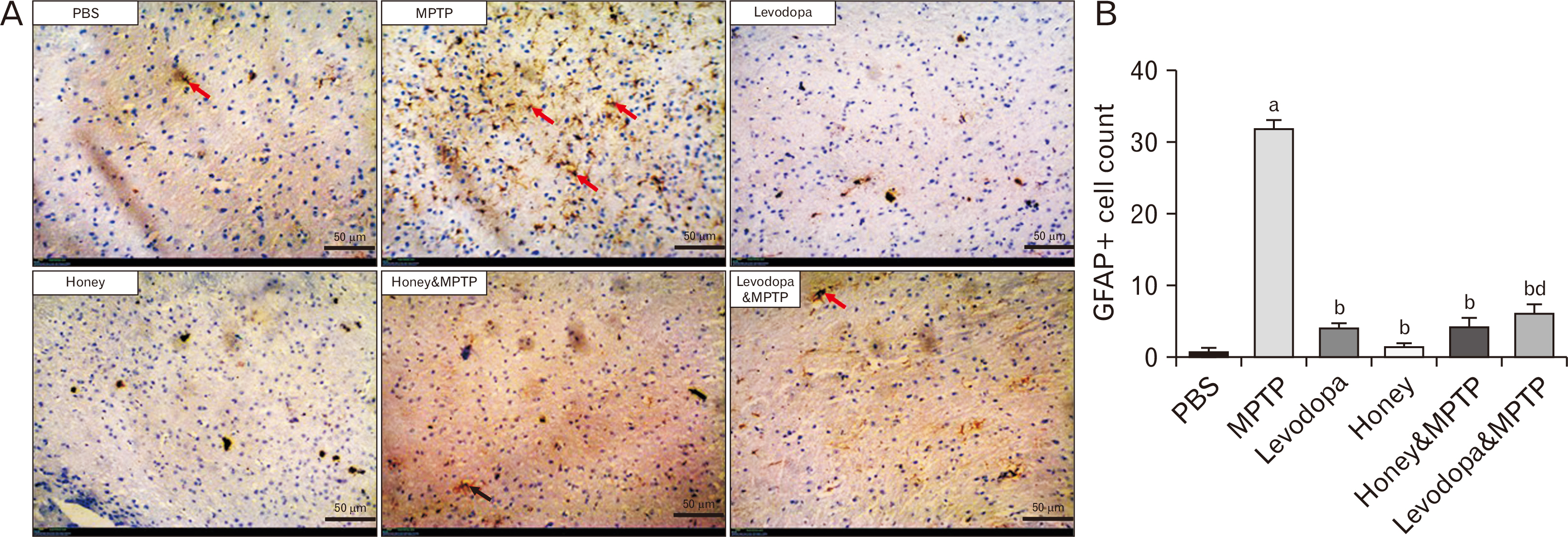

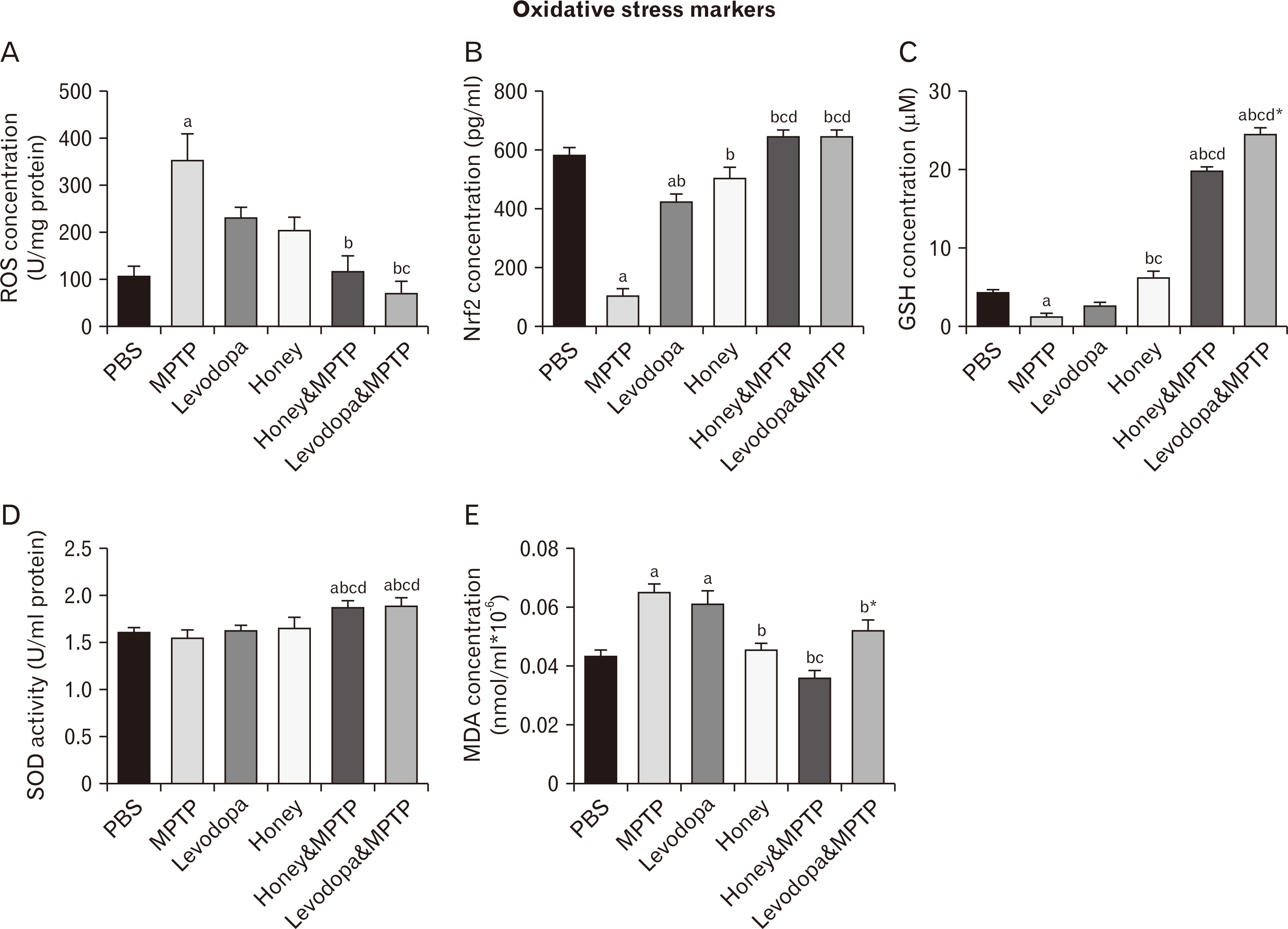

- Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects about 8.5 million individuals worldwide. Oxidative and inflammatory cascades are implicated in the neurological sequels, that are mostly unresolved in PD treatments. However, proper nutrition offers one of the most effective and least costly ways to decrease the burden of many diseases and their associated risk factors. Moreover, prevention may be the best response to the progressive nature of PD, thus, the therapeutic novelty of honey and levodopa may be prospective. This study aimed to investigate the neuroprotective role of honey and levodopa against 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced oxidative stress. Fifty-four adult male Swiss mice were divided into control and PD model groups of 27 mice. Each third of the control mice either received phosphate buffered saline, honey, or levodopa for 21 days. However, each third of the PD models was either pretreated with honey and levodopa or not pretreated. Behavioral studies and euthanasia were conducted 2 and 8 days after MPTP administration respectively. The result showed that there were significantly (P<0.05) higher motor activities in the PD models pretreated with the honey as well as levodopa. furthermore, the pretreatments protected the midbrain against the chromatolysis and astrogliosis induced by MPTP. The expression of antioxidant markers (glutathione [GSH] and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 [Nrf2]) was also significantly upregulated in the pretreated PD models. It is thus concluded that honey and levodopa comparably protected the substantia nigra pars compacta neurons against oxidative stress by modulating the Nrf2 signaling molecule thereby increasing GSH level to prevent MPTP-induced oxidative stress.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. Oct. 1. Ageing and health [Internet]. WHO;Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. cited 2023 Dec 29.2. Yang W, Hamilton JL, Kopil C, Beck JC, Tanner CM, Albin RL, Ray Dorsey E, Dahodwala N, Cintina I, Hogan P, Thompson T. 2020; Current and projected future economic burden of Parkinson's disease in the U.S. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 6:15. DOI: 10.1038/s41531-020-0117-1. PMID: 32665974. PMCID: PMC7347582.3. Tysnes OB, Storstein A. 2017; Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 124:901–5. DOI: 10.1007/s00702-017-1686-y.4. Simon DK, Tanner CM, Brundin P. 2020; Parkinson disease epidemiology, pathology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med. 36:1–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.08.002. PMID: 31733690. PMCID: PMC6905381.5. Bove C, Travagli RA. 2019; Neurophysiology of the brain stem in Parkinson's disease. J Neurophysiol. 121:1856–64. DOI: 10.1152/jn.00056.2019. PMID: 30917059. PMCID: PMC6589717.6. Kouli A, Torsney KM, Kuan WL. Stoker TB, Greenland JC, editors. Parkinson's disease: etiology, neuropathology, and pathogenesis. Parkinson's disease: pathogenesis and clinical aspects. Codon Publications;2018.7. Jenner P, Olanow CW. 1996; Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 47(6 Suppl 3):S161–70. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.47.6_Suppl_3.161S.8. Magrinelli F, Picelli A, Tocco P, Federico A, Roncari L, Smania N, Zanette G, Tamburin S. 2016; Pathophysiology of motor dysfunction in Parkinson's disease as the rationale for drug treatment and rehabilitation. Parkinsons Dis. 2016:9832839. DOI: 10.1155/2016/9832839. PMID: 27366343. PMCID: PMC4913065.9. Ball N, Teo WP, Chandra S, Chapman J. 2019; Parkinson's disease and the environment. Front Neurol. 10:218. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00218.10. Nag N, Jelinek GA. 2019; A narrative review of lifestyle factors associated with Parkinson's disease risk and progression. Neurodegener Dis. 19:51–9. DOI: 10.1159/000502292. PMID: 31487721.11. Teodoro AJ. 2019; Bioactive compounds of food: their role in the prevention and treatment of diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019:3765986. DOI: 10.1155/2019/3765986. PMID: 30984334. PMCID: PMC6432691.12. ParkinsonsDisease.net. Dietary supplements for Parkinson's disease [Internet]. ParkinsonsDisease.net.;2017. Mar. 17. cited 2023 Dec 29. Available from: https://parkinsonsdisease.net/treatment/complementary-alternative-supplements.13. Iranshahy M, Javadi B, Sahebkar A. 2022; Protective effects of functional foods against Parkinson's disease: a narrative review on pharmacology, phytochemistry, and molecular mechanisms. Phytother Res. 36:1952–89. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.7425. PMID: 35244296.14. Ali AM, Kunugi H. 2019; Bee honey protects astrocytes against oxidative stress: a preliminary in vitro investigation. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 39:312–4. DOI: 10.1002/npr2.12079. PMID: 31529692. PMCID: PMC7292328.15. Kesavan P, Banerjee A, Banerjee A, Murugesan R, Marotta F, Pathak S. Watson RR, Preedy VR, Zibadi S, editors. An overview of dietary polyphenols and their therapeutic effects. Polyphenols: mechanisms of action in human health and disease. Elsevier;2018. p. 221–35. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-813006-3.00017-9.16. Glick D. Methods of biochemical analysis. Wiley;1954. DOI: 10.1002/9780470110171.17. Percário S, da Silva Barbosa A, Varela ELP, Gomes ARQ, Ferreira MES, de Nazaré Araújo Moreira T, Dolabela MF. 2020; Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease: potential benefits of antioxidant supplementation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020:2360872. DOI: 10.1155/2020/2360872. PMID: 33101584. PMCID: PMC7576349.18. Aznavour N, Cendres-Bozzi C, Lemoine L, Buda C, Sastre JP, Mincheva Z, Zimmer L, Lin JS. 2012; MPTP animal model of Parkinsonism: dopamine cell death or only tyrosine hydroxylase impairment? A study using PET imaging, autoradiography, and immunohistochemistry in the cat. CNS Neurosci Ther. 18:934–41. DOI: 10.1111/cns.12009. PMID: 23106974. PMCID: PMC6493344.19. Zhou JS, Zhu Z, Wu F, Zhou Y, Sheng R, Wu JC, Qin ZH. 2019; NADPH ameliorates MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration through inhibiting p38MAPK activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 40:180–91. DOI: 10.1038/s41401-018-0003-0. PMID: 29769744. PMCID: PMC6329815.20. Abdulmajeed WI, Sulieman HB, Zubayr MO, Imam A, Amin A, Biliaminu SA, Oyewole LA, Owoyele BV. 2016; Honey prevents neurobehavioural deficit and oxidative stress induced by lead acetate exposure in male Wistar rats- a preliminary study. Metab Brain Dis. 31:37–44. DOI: 10.1007/s11011-015-9733-6. PMID: 26435406.21. Angelopoulou E, Pyrgelis ES, Piperi C. 2020; Neuroprotective potential of chrysin in Parkinson's disease: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Neurochem Int. 132:104612. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2019.104612. PMID: 31785348.22. Lin MW, Lin CC, Chen YH, Yang HB, Hung SY. 2019; Celastrol inhibits dopaminergic neuronal death of Parkinson's disease through activating mitophagy. Antioxidants (Basel). 9:37. DOI: 10.3390/antiox9010037. PMID: 31906147. PMCID: PMC7022523.23. Adeniyi IA, Babalola KT, Adekoya VA, Oyebanjo O, Ajayi AM, Onasanwo SA. 2023; Neuropharmacological effects of honey in lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment, anxiety and motor impairment. Nutr Neurosci. 26:511–24. DOI: 10.1080/1028415X.2022.2063578. PMID: 35470773.24. Zhang ZN, Hui Z, Chen C, Liang Y, Tang LL, Wang SL, Xu CC, Yang H, Zhang JS, Zhao Y. 2021; Neuroprotective effects and related mechanisms of echinacoside in MPTP-induced PD mice. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 17:1779–92. DOI: 10.2147/NDT.S299685. PMID: 34113108. PMCID: PMC8184243.25. Zhao Q, Cai D, Bai Y. 2013; Selegiline rescues gait deficits and the loss of dopaminergic neurons in a subacute MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Int J Mol Med. 32:883–91. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1450.26. Geldenhuys WJ, Guseman TL, Pienaar IS, Dluzen DE, Young JW. 2015; A novel biomechanical analysis of gait changes in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. PeerJ. 3:e1175. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.1175. PMID: 26339553. PMCID: PMC4558067.27. Li S, Pu XP. 2011; Neuroprotective effect of kaempferol against a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Biol Pharm Bull. 34:1291–6. DOI: 10.1248/bpb.34.1291. PMID: 21804220.28. Mijanur Rahman M, Gan SH, Khalil MI. 2014; Neurological effects of honey: current and future prospects. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014:958721. DOI: 10.1155/2014/958721. PMID: 24876885. PMCID: PMC4020454.29. Kotian SR, Bhat KMR, Padma D, Pai KSR. 2019; Influence of traditional medicines on the activity of keratinocytes in wound healing: an in-vitro study. Anat Cell Biol. 52:324–32. DOI: 10.5115/acb.19.009. PMID: 31598362. PMCID: PMC6773891.30. Hornykiewicz O. Riederer P, Reichmann H, Youdim MBH, Gerlach M, editors. The discovery of dopamine deficiency in the parkinsonian brain. Parkinson's disease and related disorders. Springer Vienna;2006. p. 9–15. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_3.31. Gao JX, Li Y, Wang SN, Chen XC, Lin LL, Zhang H. 2019; Overexpression of microRNA-183 promotes apoptosis of substantia nigra neurons via the inhibition of OSMR in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Int J Mol Med. 43:209–20. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3982.32. Castelli V, Grassi D, Bocale R, d'Angelo M, Antonosante A, Cimini A, Ferri C, Desideri G. 2018; Diet and brain health: which role for polyphenols? Curr Pharm Des. 24:227–38. DOI: 10.2174/1381612824666171213100449. PMID: 29237377.33. Yasuda Y, Shimoda T, Uno K, Tateishi N, Furuya S, Yagi K, Suzuki K, Fujita S. 2008; The effects of MPTP on the activation of microglia/astrocytes and cytokine/chemokine levels in different mice strains. J Neuroimmunol. 204:43–51. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.08.003. PMID: 18817984.34. O'Callaghan JP, Seidler FJ. 1992; 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced astrogliosis does not require activation of ornithine decarboxylase. Neurosci Lett. 148:105–8. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90815-O.35. Serra PA, Sciola L, Delogu MR, Spano A, Monaco G, Miele E, Rocchitta G, Miele M, Migheli R, Desole MS. 2002; The neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine induces apoptosis in mouse nigrostriatal glia. Relevance to nigral neuronal death and striatal neurochemical changes. J Biol Chem. 277:34451–61. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M202099200. PMID: 12084711.36. MacMahon Copas AN, McComish SF, Fletcher JM, Caldwell MA. 2021; The pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease: a complex interplay between astrocytes, microglia, and T lymphocytes? Front Neurol. 12:666737. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2021.666737. PMID: 34122308. PMCID: PMC8189423.37. Minden-Birkenmaier BA, Cherukuri K, Smith RA, Radic MZ, Bowlin GL. 2019; Manuka honey modulates the inflammatory behavior of a dHL-60 neutrophil model under the cytotoxic limit. Int J Biomater. 2019:6132581. DOI: 10.1155/2019/6132581. PMID: 30936919. PMCID: PMC6415307.38. Middeldorp J, Hol EM. 2011; GFAP in health and disease. Prog Neurobiol. 93:421–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.005. PMID: 21219963.39. Manoharan S, Guillemin GJ, Abiramasundari RS, Essa MM, Akbar M, Akbar MD. 2016; The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and Huntington's disease: a mini review. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016:8590578. DOI: 10.1155/2016/8590578. PMID: 28116038. PMCID: PMC5223034.40. Gluck MR, Krueger MJ, Ramsay RR, Sablin SO, Singer TP, Nicklas WJ. 1994; Characterization of the inhibitory mechanism of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium and 4-phenylpyridine analogs in inner membrane preparations. J Biol Chem. 269:3167–74. DOI: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)41844-8. PMID: 8106350.41. Ahmad A, Khan RA, Mesaik MA. 2009; Anti inflammatory effect of natural honey on bovine thrombin-induced oxidative burst in phagocytes. Phytother Res. 23:801–8. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.2648. PMID: 19142984.42. Hunter M, Kellett J, D'Cunha NM, Toohey K, McKune A, Naumovski N. 2020; The effect of honey as a treatment for oral ulcerative lesions: a systematic review. Explor Res Hypothesis Med. 5:27–37. DOI: 10.14218/ERHM.2019.00029.43. Ayala A, Muñoz MF, Argüelles S. 2014; Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014:360438. DOI: 10.1155/2014/360438. PMID: 24999379. PMCID: PMC4066722.44. Liu C, Kershberg L, Wang J, Schneeberger S, Kaeser PS. 2018; Dopamine secretion is mediated by sparse active zone-like release sites. Cell. 172:706–18.e15. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.008. PMID: 29398114. PMCID: PMC5807134.45. Agil A, Durán R, Barrero F, Morales B, Araúzo M, Alba F, Miranda MT, Prieto I, Ramírez M, Vives F. 2006; Plasma lipid peroxidation in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Role of the L-dopa. J Neurol Sci. 240:31–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.016. PMID: 16219327.46. Adekeye AO, Irawo GJ, Fafure AA. 2020; Ficus exasperata Vahl leaves extract attenuates motor deficit in vanadium-induced parkinsonism mice. Anat Cell Biol. 53:183–93. DOI: 10.5115/acb.19.205. PMID: 32647086. PMCID: PMC7343565.47. Erejuwa OO, Sulaiman SA, Ab Wahab MS, Sirajudeen KN, Salleh S, Gurtu S. 2012; Honey supplementation in spontaneously hypertensive rats elicits antihypertensive effect via amelioration of renal oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012:374037. DOI: 10.1155/2012/374037. PMID: 22315654. PMCID: PMC3270456.48. Awasthi YC, Chaudhary P, Vatsyayan R, Sharma A, Awasthi S, Sharma R. 2009; Physiological and pharmacological significance of glutathione-conjugate transport. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 12:540–51. DOI: 10.1080/10937400903358975. PMID: 20183533.49. Aoyama K, Matsumura N, Watabe M, Nakaki T. 2008; Oxidative stress on EAAC1 is involved in MPTP-induced glutathione depletion and motor dysfunction. Eur J Neurosci. 27:20–30. DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05979.x. PMID: 18093171.50. Wang Y, Li D, Cheng N, Gao H, Xue X, Cao W, Sun L. 2015; Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity of vitex honey against paracetamol induced liver damage in mice. Food Funct. 6:2339–49. DOI: 10.1039/C5FO00345H. PMID: 26084988.51. Younes-Mhenni S, Frih-Ayed M, Kerkeni A, Bost M, Chazot G. 2007; Peripheral blood markers of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Eur Neurol. 58:78–83. DOI: 10.1159/000103641. PMID: 17565220.52. Brandes MS, Zweig JA, Tang A, Gray NE. 2021; NRF2 activation ameliorates oxidative stress and improves mitochondrial function and synaptic plasticity, and in A53T α-synuclein hippocampal neurons. Antioxidants (Basel). 11:26. DOI: 10.3390/antiox11010026. PMID: 35052530. PMCID: PMC8772776.53. Almasaudi SB, Abbas AT, Al-Hindi RR, El-Shitany NA, Abdel-Dayem UA, Ali SS, Saleh RM, Al Jaouni SK, Kamal MA, Harakeh SM. 2017; Manuka honey exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities that promote healing of acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017:5413917. DOI: 10.1155/2017/5413917. PMID: 28250794. PMCID: PMC5307292.54. Esteras N, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY. 2016; Nrf2 activation in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: a focus on its role in mitochondrial bioenergetics and function. Biol Chem. 397:383–400. DOI: 10.1515/hsz-2015-0295. PMID: 26812787.55. von Otter M, Landgren S, Nilsson S, Celojevic D, Bergström P, Håkansson A, Nissbrandt H, Drozdzik M, Bialecka M, Kurzawski M, Blennow K, Nilsson M, Hammarsten O, Zetterberg H. 2010; Association of Nrf2-encoding NFE2L2 haplotypes with Parkinson's disease. BMC Med Genet. 11:36. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-36. PMID: 20196834. PMCID: PMC2843602.56. Anandhan A, Nguyen N, Syal A, Dreher LA, Dodson M, Zhang DD, Madhavan L. 2021; NRF2 loss accentuates Parkinsonian pathology and behavioral dysfunction in human α-synuclein overexpressing mice. Aging Dis. 12:964–82. DOI: 10.14336/AD.2021.0511. PMID: 34221542. PMCID: PMC8219498.57. Chen PC, Vargas MR, Pani AK, Smeyne RJ, Johnson DA, Kan YW, Johnson JA. 2009; Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease: critical role for the astrocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106:2933–8. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0813361106. PMID: 19196989. PMCID: PMC2650368.58. Alvarez-Suarez JM, Giampieri F, Cordero M, Gasparrini M, Forbes-Hernández TY, Mazzoni L, Afrin S, Beltrán-Ayala P, González-Paramás AM, Santos-Buelga C, Varela-Lopez A, Quiles JL, Battino M. 2016; Activation of AMPK/Nrf2 signalling by Manuka honey protects human dermal fibroblasts against oxidative damage by improving antioxidant response and mitochondrial function promoting wound healing. J Funct Foods. 25:38–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.05.008.59. Ranneh Y, Akim AM, Hamid HA, Khazaai H, Fadel A, Mahmoud AM. 2019; Stingless bee honey protects against lipopolysaccharide induced-chronic subclinical systemic inflammation and oxidative stress by modulating Nrf2, NF-κB and p38 MAPK. Nutr Metab (Lond). 16:15. DOI: 10.1186/s12986-019-0341-z. PMID: 30858869. PMCID: PMC6391794.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Neuroprotective Effect of β-Lapachone in MPTP-Induced Parkinson's Disease Mouse Model: Involvement of Astroglial p-AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathways

- Effects of Nicotine on MPTP-induced Parkinson's Disease Animal Model

- Genetic Basis of Parkinson Disease

- 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in Rodent Models of Parkinson's Disease through Inhibition of Microglial Activation

- The Effect of Ginseng Saponin on the Dopaminergic Neurons in the Parkinson's Disease Model in Mice