J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Aug;39(33):e233. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e233.

Psychological Distress Trends and Effect of Media Exposure Among Community Residents After the Seoul Halloween Crowd Crush

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Psychiatry, CHA University Ilsan Medical Center, Goyang, Korea

- 3Division of Biostatistics, Department of Academic Research, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Workplace Mental Health Institute, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Media Real Research Korea Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2559225

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e233

Abstract

- Background

It is unclear how exposure to and perception of community trauma creates a mental health burden. This study aimed to examine the psychological distress trends among community residents in acute stress reaction, acute stress disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder phases following the Seoul Halloween crowd crush.

Methods

A three-wave repeated cross-sectional survey was conducted with participants after the incident. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with post hoc Bonferroni test was adopted to examine temporal changes in psychological distress and psychological outcomes resulting from media impacts. A two-way ANCOVA was adopted to examine the interaction effects of time and relevance to victims on psychological distress.

Results

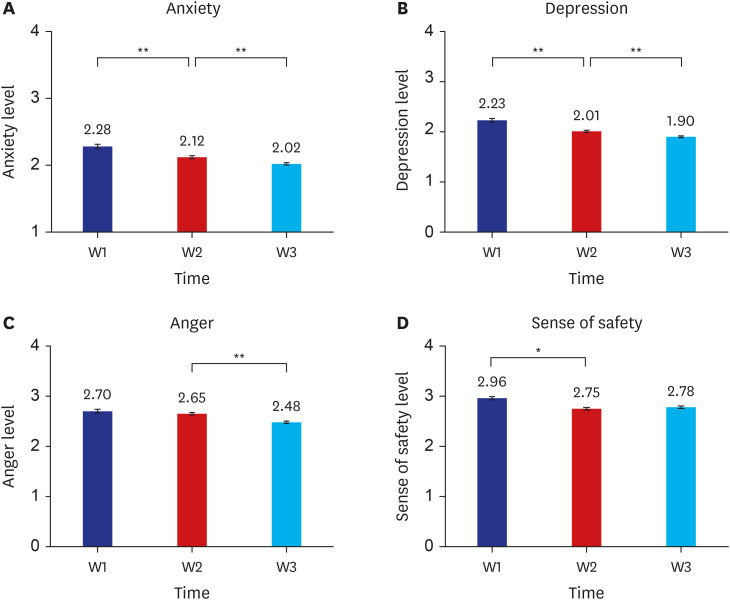

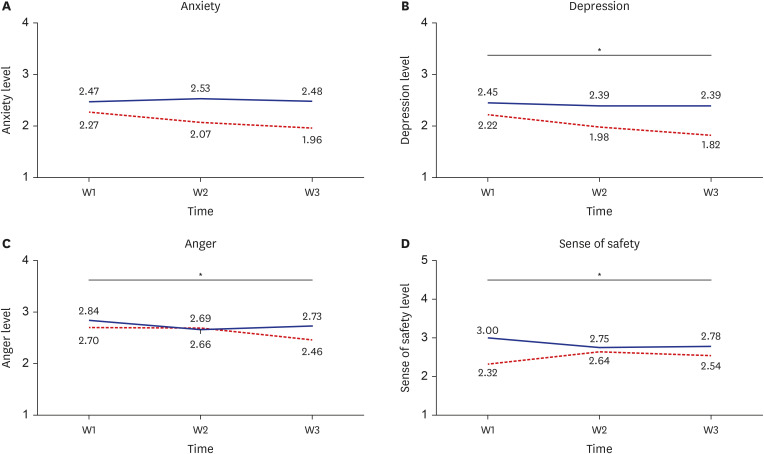

A total of 807, 1,703, and 2,220 individuals participated in the three waves. Anxiety (estimated mean [standard error of the mean]: 2.28 [0.03] vs. 2.12 [0.02] vs. 2.03 [0.02]; P < 0.001), depression (2.22 [0.03] vs. 2.01 [0.02] vs. 1.90 [0.02]; P < 0.001), and anger (2.70 [0.03] vs. 2.66 [0.02] vs. 2.49 [0.02]; P < 0.001) gradually improved. However, sense of safety initially worsened and did not recover well (2.96 [0.03] vs. 2.75 [0.02] vs. 2.77 [0.02]; P < 0.001). The interaction effect of time and relevance to the victim were significant in depression (P for interaction = 0.049), anger (P for interaction = 0.016), and sense of safety (P for interaction = 0.004). Among participants unrelated to the victim, those exposed to graphics exhibited higher levels of anxiety (2.09 [0.02] vs. 1.87 [0.07]; P = 0.002), depression (1.99 [0.02] vs. 1.83 [0.07]; P = 0.020), and anger (2.71 [0.03] vs. 2.47 [0.08]; P = 0.003) at W2 and higher anger (2.49 [0.02] vs. 2.31 [0.06]; P = 0.005) at W3.

Conclusion

Community residents indirectly exposed to trauma also experienced psychological distress in the early stages after the incident. A significant impact of media which might have served as a conduit for unfiltered graphics and rumors was also indicated.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Sharma A, McCloskey B, Hui DS, Rambia A, Zumla A, Traore T, et al. Global mass gathering events and deaths due to crowd surge, stampedes, crush and physical injuries - lessons from the Seoul Halloween and other disasters. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023; 52:102524. PMID: 36516965.2. Matt GE, Vázquez C. Anxiety, depressed mood, self-esteem, and traumatic stress symptoms among distant witnesses of the 9/11 terrorist attacks: transitory responses and psychological resilience. Span J Psychol. 2008; 11(2):503–515. PMID: 18988435.3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C., USA: American Psychiatric Association;2013.4. Holman EA, Garfin DR, Lubens P, Silver RC. Media exposure to collective trauma, mental health, and functioning: does it matter what you see? Clin Psychol Sci. 2019; 8(1):111–124.5. Goodwin R, Palgi Y, Hamama-Raz Y, Ben-Ezra M. In the eye of the storm or the bullseye of the media: social media use during Hurricane Sandy as a predictor of post-traumatic stress. J Psychiatr Res. 2013; 47(8):1099–1100. PMID: 23673141.6. Holman EA, Garfin DR, Silver RC. Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111(1):93–98. PMID: 24324161.7. Ni MY, Yao XI, Leung KS, Yau C, Leung CM, Lun P, et al. Depression and post-traumatic stress during major social unrest in Hong Kong: a 10-year prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020; 395(10220):273–284. PMID: 31928765.8. Neria Y, Sullivan GM. Understanding the mental health effects of indirect exposure to mass trauma through the media. JAMA. 2011; 306(12):1374–1375. PMID: 21903818.9. Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, Ahern J, Susser E, Gold J, et al. Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2003; 158(6):514–524. PMID: 12965877.10. Dick AS, Silva K, Gonzalez R, Sutherland MT, Laird AR, Thompson WK, et al. Neural vulnerability and hurricane-related media are associated with post-traumatic stress in youth. Nat Hum Behav. 2021; 5(11):1578–1589. PMID: 34795422.11. Somasundaram D. Collective trauma in the Vanni-a qualitative inquiry into the mental health of the internally displaced due to the civil war in Sri Lanka. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010; 4(1):22. PMID: 20667090.12. Neria Y, Besser A, Kiper D, Westphal M. A longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and generalized anxiety disorder in Israeli civilians exposed to war trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2010; 23(3):322–330. PMID: 20564364.13. Kim SY, Yang K, Oh IH, Park S, Cheong HK, Hwang JW. Incidence and direct medical cost of acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in Korea: based on National Health Insurance Service Claims Data from 2011 to 2017. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(18):e125. PMID: 33975398.14. Wong A, Lee HS, Lee HP, Choi YK, Lee JH. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and posttraumatic growth following indirect trauma from the Sewol Ferry disaster, 2014. Psychiatry Investig. 2018; 15(6):613–619.15. Lee JY, Kim SW, Kang HJ, Kim SY, Bae KY, Kim JM, et al. Relationship between problematic internet use and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among students following the Sewol Ferry disaster in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig. 2017; 14(6):871–875.16. Oh JK, Lee MS, Bae SM, Kim E, Hwang JW, Chang HY, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and clinical diagnosis in high school students exposed to the Sewol Ferry disaster. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(5):e38. PMID: 30718991.17. Lee JY, Kim SW, Kim JM. The impact of community disaster trauma: a focus on emerging research of PTSD and other mental health outcomes. Chonnam Med J. 2020; 56(2):99–107. PMID: 32509556.18. Spielberger CD, Reheiser EC. Assessment of emotions: anxiety, anger, depression, and curiosity. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2009; 1(3):271–302.19. Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 Disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry. 2002; 65(3):207–239. PMID: 12405079.20. Shalev AY, Freedman S. PTSD following terrorist attacks: a prospective evaluation. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162(6):1188–1191. PMID: 15930068.21. Pfefferbaum B, Palka JM, North CS. Associations between news media coverage of the 11 September attacks and depression in employees of New York City area businesses. Behav Sci (Basel). 2021; 11(3):29. PMID: 33673572.22. Han H, Noh JW, Huh HJ, Huh S, Joo JY, Hong JH, et al. Effects of mental health support on the grief of bereaved people caused by Sewol Ferry accident. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(7):1173–1180. PMID: 28581276.23. Forbes D, Alkemade N, Waters E, Gibbs L, Gallagher C, Pattison P, et al. The role of anger and ongoing stressors in mental health following a natural disaster. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015; 49(8):706–713. PMID: 25586750.24. Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA. 2002; 288(10):1235–1244. PMID: 12215130.25. Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003; 129(1):52–73. PMID: 12555794.26. Hobfoll SE, Watson P, Bell CC, Bryant RA, Brymer MJ, Friedman MJ, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: empirical evidence. Psychiatry. 2021; 84(4):311–346. PMID: 35061969.27. Beiser M, Wiwa O, Adebajo S. Human-initiated disaster, social disorganization and post-traumatic stress disorder above Nigeria’s oil basins. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 71(2):221–227. PMID: 20471148.28. Bryant RA. Cognitive behavior therapy: implications from advances in neuroscience. Kato N, Kawata M, Pitman RK, editors. PTSD: Brain Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Tokyo, Japan: Springer Japan;2006. p. 255–269.29. Pfefferbaum B, Newman E, Nelson SD, Nitiéma P, Pfefferbaum RL, Rahman A. Disaster media coverage and psychological outcomes: descriptive findings in the extant research. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014; 16(9):464. PMID: 25064691.30. Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol use, and perceived safety after the terrorist attack on the pentagon. Psychiatr Serv. 2003; 54(10):1380–1382. PMID: 14557524.31. Gaffney DA. The aftermath of disaster: children in crisis. J Clin Psychol. 2006; 62(8):1001–1016. PMID: 16700019.32. Gibbs L, Block K, Harms L, MacDougall C, Baker E, Ireton G, et al. Children and young people’s wellbeing post-disaster: safety and stability are critical. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015; 14:195–201.33. North CS, McCutcheon V, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM. Three-year follow-up of survivors of a mass shooting episode. J Urban Health. 2002; 79(3):383–391. PMID: 12200507.34. Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC, Gleser GC, Leonard AC, Korol M, et al. Buffalo Creek survivors in the second decade: stability of stress symptoms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1990; 60(1):43–54. PMID: 2305844.35. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox L, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliott MN, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345(20):1507–1512. PMID: 11794216.36. Smith EM, North CS, McCool RE, Shea JM. Acute postdisaster psychiatric disorders: identification of persons at risk. Am J Psychiatry. 1990; 147(2):202–206. PMID: 2301660.37. Amstadter AB, Vernon LL. Emotional reactions during and after trauma: a comparison of trauma types. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2008; 16(4):391–408. PMID: 20046534.38. Small DA, Lerner JS, Fischhoff B. Emotion priming and attributions for terrorism: Americans’ reactions in a national field experiment. Polit Psychol. 2006; 27(2):289–298.39. Palgi Y, Dicker-Oren SD, Greene T. Evaluating a community fire as human-made vs. natural disaster moderates the relationship between peritraumatic distress and both PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020; 33(5):569–580. PMID: 32319328.40. Yates S. Attributions about the causes and consequences of cataclysmic events. J Pers Interpers Loss. 1998; 3(1):7–24.41. Iyengar S. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL, USA: University of Chicago Press;1991.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Injury to the Left Sciatic and Right Common Peroneal Nerves Combined With Multifocal Rhabdomyolysis in a Survivor of the Itaewon Crowd Crush: A Case Report

- The Moderating Effect of Resilience on the Relationship Between the Relevance to Victims With Post-Trauma Psychiatric Symptoms of Community Residents After Seoul Halloween Crowd Crush

- Letter to the Editor: Nerve Entrapment From a Crush Injury During the Halloween Mass Casualty Accident in Itaewon

- Forbearance Coping, Community Resilience, Family Resilience and Mental Health During the Post-Pandemic in China: A Moderated Mediation Model

- A Structural Equation Model of the Relationship Between Symptom Burden, Psychological Resilience, Coping Styles, Social Support, and Psychological Distress in Elderly Patients With Acute Exacerbation Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in China