J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Sep;39(35):e242. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e242.

Public and Clinician Perspectives on Ventilator Withdrawal in Vegetative State Following Severe Acute Brain Injury: A Vignette Survey

- Affiliations

-

- 1Center for Palliative Care and Clinical Ethics, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Center for Integrative Care Hub, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Yonsei University Severance Children’s Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Chungnam National University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea

- 6Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2559195

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e242

Abstract

- Background

The vegetative state (VS) after severe acute brain injury (SABI) is associated with significant prognostic uncertainty and poor long-term functional outcomes. However, it is generally distinguished from imminent death and is exempt from the Life-Sustaining Treatment (LST) Decisions Act in Korea. Here, we aimed to examine the perspectives of the general population (GP) and clinicians regarding decisions on mechanical ventilator withdrawal in patients in a VS after SABI.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was undertaken, utilizing a self-reported online questionnaire based on a case vignette. Nationally selected by quota sampling, the GP comprised 500 individuals aged 20 to 69 years. There were 200 doctors from a tertiary university hospital in the clinician sample. Participants were asked what they thought about mechanical ventilator withdrawal in patients in VS 2 months and 3 years after SABI.

Results

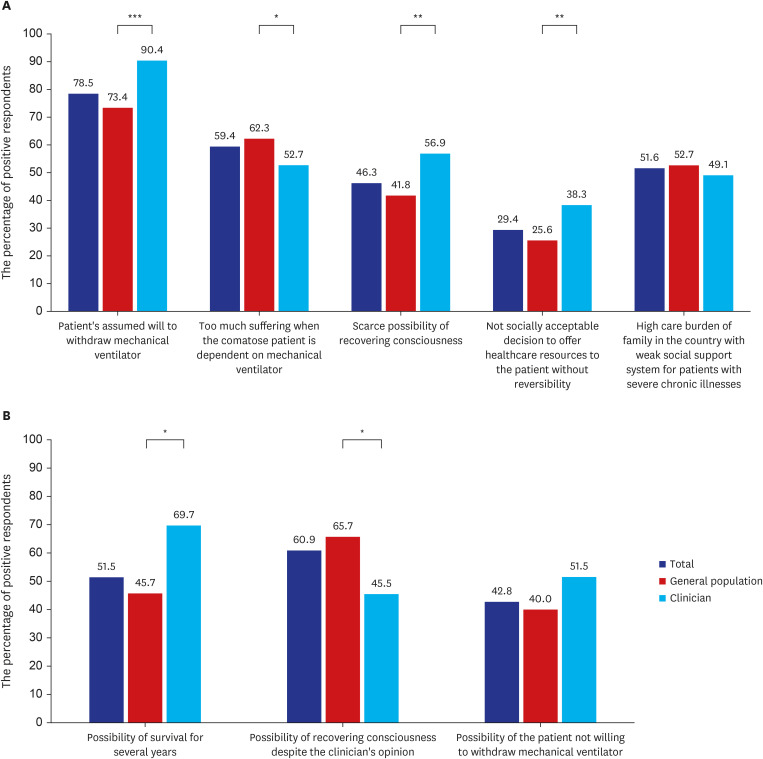

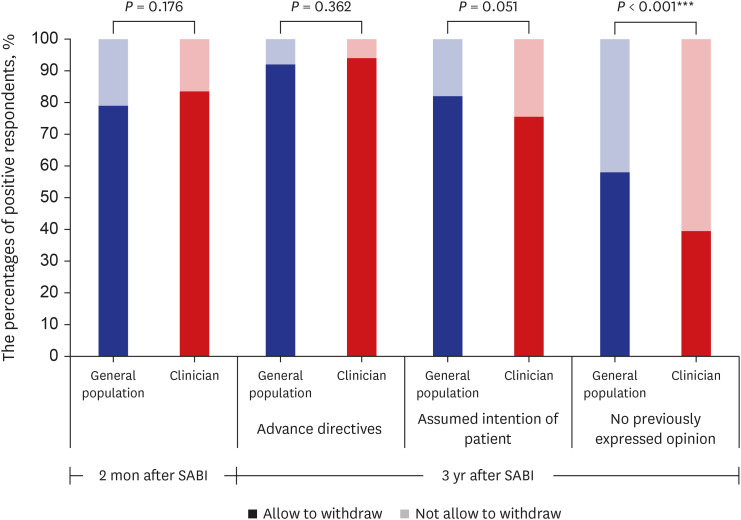

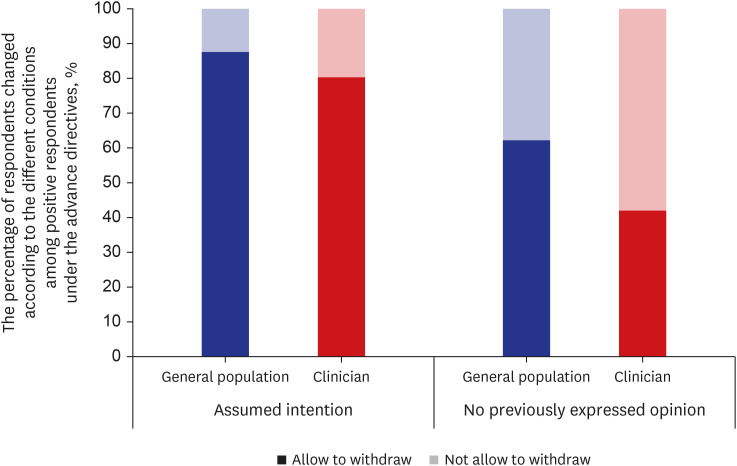

Two months after SABI in the case, 79% of the GP and 83.5% of clinicians had positive attitudes toward mechanical ventilator withdrawal. In the GP, attitudes were associated with spirituality, household income, religion, the number of household members. On the other hand, clinicians’ attitudes were related to their experience of completing advance directives (AD) and making decisions about LST. In this case, 3 years after SABI, 92% of the GP and 94% of clinicians were more accepting of ventilator withdrawal compared to previous responses, based on the assumption that the patient had written AD. However, it appeared that the proportion of positive responses to ventilator withdrawal decreased when the patients had only verbal expressions (82% of the GP; 75.5% of clinicians) or had not previously expressed an opinion regarding LST (58% of the GP; 39.5% of clinicians).

Conclusion

More than three quarters of both the GP and clinicians had positive opinions regarding ventilator withdrawal in patients in a VS after SABI, which was reinforced with time and the presence of AD. Legislative adjustments are needed to ensure that previous wishes for those patients are more respected and reflected in treatment decisions.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Giacino JT, Katz DI, Schiff ND, Whyte J, Ashman EJ, Ashwal S, et al. Practice guideline update recommendations summary: Disorders of consciousness: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Neurology. 2018; 91(10):450–460. PMID: 30089618.2. Jennett B. The vegetative state. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73(4):355–357. PMID: 12235296.3. Lee YS, Lee HY, Leigh JH, Choi Y, Kim HK, Oh BM. The socioeconomic burden of acquired brain injury among the Korean patients over 20 years of age in 2015–2017: a prevalence-based approach. Brain Neurorehabil. 2021; 14(3):e24. PMID: 36741222.4. Kim HK, Leigh JH, Kim TW, Oh BM. Epidemiological trends and rehabilitation utilization of traumatic brain injury in Korea (2008–2018). Brain Neurorehabil. 2021; 14(3):e25. PMID: 36741218.5. Bae SW, Lee MY. Incidence of traumatic brain injury by severity among work-related injured workers from 2010 to 2019: an analysis of workers’ compensation insurance data in Korea. J Occup Environ Med. 2022; 64(9):731–736. PMID: 35673265.6. Yang SN, Park SW, Jung HY, Rah UW, Kim YH, Chun MH, et al. Korean brain rehabilitation registry for rehabilitation of persons with brain disorders: annual report in 2009. J Korean Med Sci. 2012; 27(6):691–696. PMID: 22690103.7. Septien S, Rubin MA. Disorders of consciousness: ethical issues of diagnosis, treatment, and prognostication. Semin Neurol. 2018; 38(5):548–554. PMID: 30321893.8. Picozzi M, Panzeri L, Torri D, Sattin D. Analyzing the paradigmatic cases of two persons with a disorder of consciousness: reflections on the legal and ethical perspectives. BMC Med Ethics. 2021; 22(1):88. PMID: 34238274.9. Jennett B. Thirty years of the vegetative state: clinical, ethical and legal problems. Prog Brain Res. 2005; 150:537–543. PMID: 16186047.10. Lee I. South Korea’s end-of-life care decisions act: law for better end-of-life care. Cheung D, Dunn M, editors. Advance Directives Across Asia: a Comparative Socio-Legal Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;2023. p. 57–74.11. Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy. White Papers on the Law on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment. Seoul, Korea: Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy;2018.12. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Act on hospice and palliative care and decisions on life-sustaining treatment for patients at the end of life. Accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=hospice&x=26&y=25#liBgcolor0 .13. Yoo SH, Kim Y, Choi W, Shin J, Kim MS, Park HY, et al. Ethical issues referred to clinical ethics support at a university hospital in Korea: three-year experience after enforcement of life-sustaining treatment decisions act. J Korean Med Sci. 2023; 38(24):e182. PMID: 37337807.14. Yoo SH, Choi K, Nam S, Yoon EK, Sohn JW, Oh BM, et al. Development of Korea Neuroethics guidelines. J Korean Med Sci. 2023; 38(25):e193. PMID: 37365727.15. Puchalski CM. Spirituality and the care of patients at the end-of-life: an essential component of care. Omega (Westport). 2007-2008; 56(1):33–46.16. Wikstøl D, Horn MA, Pedersen R, Magelssen M. Citizen attitudes to non-treatment decision making: a Norwegian survey. BMC Med Ethics. 2023; 24(1):20. PMID: 36890542.17. Kondziella D, Cheung MC, Dutta A. Public perception of the vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a crowdsourced study. PeerJ. 2019; 7:e6575. PMID: 30863687.18. Gipson J, Kahane G, Savulescu J. Attitudes of lay people to withdrawal of treatment in brain damaged patients. Neuroethics. 2014; 7(1):1–9. PMID: 24600485.19. Demertzi A, Ledoux D, Bruno MA, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Gosseries O, Soddu A, et al. Attitudes towards end-of-life issues in disorders of consciousness: a European survey. J Neurol. 2011; 258(6):1058–1065. PMID: 21221625.20. Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Myatra SN, Chan YH, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(3):363–371. PMID: 25581712.21. van Veen E, van der Jagt M, Citerio G, Stocchetti N, Epker JL, Gommers D, et al. End-of-life practices in traumatic brain injury patients: report of a questionnaire from the CENTER-TBI study. J Crit Care. 2020; 58:78–88. PMID: 32387842.22. Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell DW, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001; 56(6):766–772. PMID: 11274312.23. Geocadin RG, Buitrago MM, Torbey MT, Chandra-Strobos N, Williams MA, Kaplan PW. Neurologic prognosis and withdrawal of life support after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2006; 67(1):105–108. PMID: 16832087.24. Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, Simard JF, Scales DC, Burns KE, Moore L, et al. Mortality associated with withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a Canadian multicentre cohort study. CMAJ. 2011; 183(14):1581–1588. PMID: 21876014.25. Geurts M, Macleod MR, van Thiel GJ, van Gijn J, Kappelle LJ, van der Worp HB. End-of-life decisions in patients with severe acute brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2014; 13(5):515–524. PMID: 24675048.26. Kitzinger J, Kitzinger C. Deaths after feeding-tube withdrawal from patients in vegetative and minimally conscious states: a qualitative study of family experience. Palliat Med. 2018; 32(7):1180–1188. PMID: 29569993.27. Turner-Stokes L, Thakur V, Dungca C, Clare C, Alfonso E. End-of-life care for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness following withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment: experience and lessons from an 8-year cohort. Clin Med (Lond). 2022; 22(6):559–565. PMID: 36427896.28. Tsai DFC. The law and practice of advance directives in Taiwan. Cheung D, Dunn M, editors. Advance Directives Across Asia: a Comparative Socio-Legal Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press;2023. p. 75–89.29. Wakatake H, Hayashi K, Kitano Y, Hsu HC, Yoshida T, Masui Y, et al. Eleven-year retrospective study characterizing patients with severe brain damage and poor neurological prognosis -role of physicians’ attitude toward life-sustaining treatment. BMC Palliat Care. 2022; 21(1):79. PMID: 35581603.30. Chang DW, Neville TH, Parrish J, Ewing L, Rico C, Jara L, et al. Evaluation of time-limited trials among critically ill patients with advanced medical illnesses and reduction of nonbeneficial ICU treatments. JAMA Intern Med. 2021; 181(6):786–794. PMID: 33843946.31. Sprung CL, Maia P, Bulow HH, Ricou B, Armaganidis A, Baras M, et al. The importance of religious affiliation and culture on end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33(10):1732–1739. PMID: 17541550.32. Bülow HH, Sprung CL, Baras M, Carmel S, Svantesson M, Benbenishty J, et al. Are religion and religiosity important to end-of-life decisions and patient autonomy in the ICU? The Ethicatt study. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38(7):1126–1133. PMID: 22527070.33. Park SY, Phua J, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Kang Y, Tada K, et al. End-of-life care in ICUs in East Asia: a comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46(7):1114–1124. PMID: 29629982.34. Jox RJ, Kuehlmeyer K, Klein AM, Herzog J, Schaupp M, Nowak DA, et al. Diagnosis and decision making for patients with disorders of consciousness: a survey among family members. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015; 96(2):323–330. PMID: 25449192.35. Breitbart W, Heller KS. Reframing hope: meaning-centered care for patients near the end of life. Interview by Karen S. Heller. J Palliat Med. 2003; 6(6):979–988. PMID: 14733692.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Emerging Therapies in Vegetative and Minimally Conscious State after Brain Injury

- A Clinical Study on Patients in a Vegetative State after Severe Head Injury

- Certain Considerations of the Persistant Vegetative State

- Assessment of Patients with Minimally Conscious State: Recent Advances

- Life Expectancy of The Posttraumatic Persistent Vegetative State: Review of Literature and A Proposal