Arch Hand Microsurg.

2024 Sep;29(3):133-139. 10.12790/ahm.24.0015.

Epidemiology of pediatric hand lacerations: a retrospective cohort study focusing on age and injury-causing objects

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Gwangmyeong Sungae General Hospital, Gwangmyeong, Korea

- KMID: 2558736

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12790/ahm.24.0015

Abstract

- Purpose

This study analyzed the epidemiology of pediatric hand lacerations in children under 6 years old, focusing on age-related characteristics and the household objects that caused these injuries.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of patients under 6 years old who presented with hand lacerations at our emergency department from January 2016 to December 2023. Data were collected on demographics, injury-related factors (the affected hand and finger, injury location, and injury-causing object), need for surgical intervention, and damage to deep structures. Patients were categorized as infants (0–1 years), toddlers (1–3 years), or preschoolers (3–6 years). We recorded the frequency, surgical intervention rates, and affected deep structures for each injury-causing object.

Results

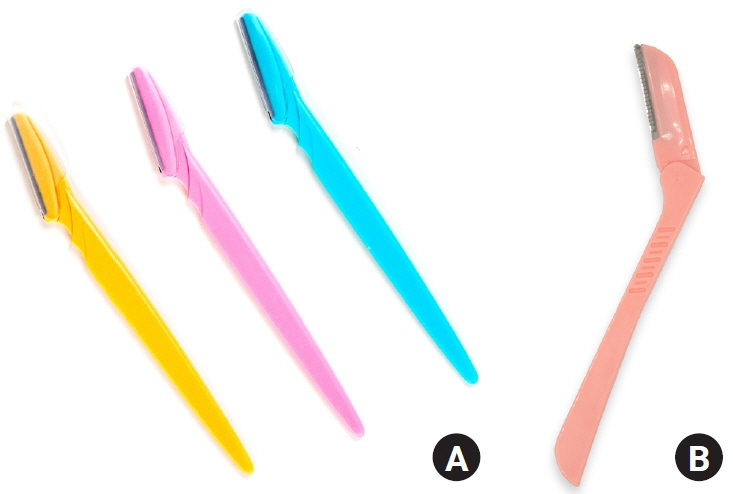

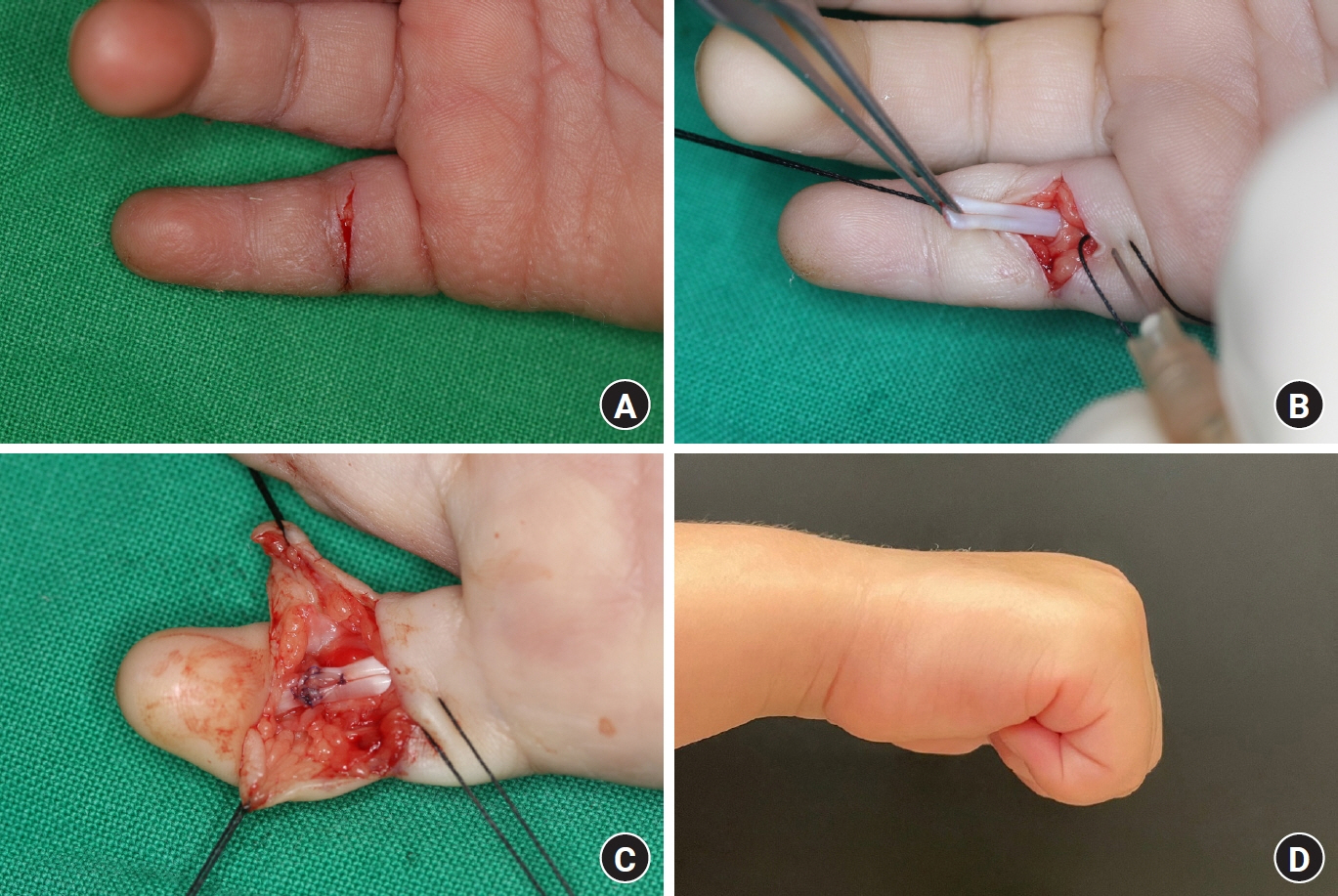

Of 153 children treated for hand lacerations, toddlers were the most frequently injured (47.7%), followed by preschoolers (44.4%) and infants (7.8%). The index and middle fingers were particularly vulnerable in toddlers and preschoolers, while infantile injuries more commonly affected the palm. Among 31 identified objects, knives/blades, particularly cutting knives (13.7%) and broken glass (13.1%), were the leading causes, with injuries occurring primarily at home. Surgical intervention was necessary in 11.1% of cases, with eyebrow razors (33.3%) most often requiring surgery and causing damage to deep structures, including arteries, nerves, and flexor tendons.

Conclusion

The study highlights the significant role of developmental behaviors in pediatric hand laceration risk. Many injuries were caused by everyday household objects, including eyebrow razors, that are often underestimated as potential dangers. Preventive measures and guardian education are crucial to reduce the incidence of these injuries.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Jeon BJ, Lee JI, Roh SY, Kim JS, Lee DC, Lee KJ. Analysis of 344 hand injuries in a pediatric population. Arch Plast Surg. 2016; 43:71–6.

Article2. Fetter-Zarzeka A, Joseph MM. Hand and fingertip injuries in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002; 18:341–5.

Article3. Bhende MS, Dandrea LA, Davis HW. Hand injuries in children presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1993; 22:1519–23.

Article4. Davis JL, Crick JC. Pediatric hand injuries. Types and general treatment considerations. AORN J. 1988; 48:237–9, 242-5, 248-9.5. Fukumasa H, Kobayashi M, Okahata Y, Nishiyama K. Epidemiology of pediatric hand injury at a pediatric department in Japan. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022; 38:582–8.

Article6. Shah SS, Rochette LM, Smith GA. Epidemiology of pediatric hand injuries presenting to United States emergency departments, 1990 to 2009. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012; 72:1688–94.

Article7. Yorlets RR, Busa K, Eberlin KR, et al. Fingertip injuries in children: epidemiology, financial burden, and implications for prevention. Hand (N Y). 2017; 12:342–7.

Article8. Satku M, Puhaindran ME, Chong AK. Characteristics of fingertip injuries in children in Singapore. Hand Surg. 2015; 20:410–4.

Article9. Liu WH, Lok J, Lau MS, et al. Mechanism and epidemiology of paediatric finger injuries at Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2015; 21:237–42.

Article10. Witsaman RJ, Comstock RD, Smith GA. Pediatric fireworks-related injuries in the United States: 1990-2003. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:296–303.

Article11. Liodaki E, Kisch T, Mauss KL, et al. Management of pediatric hand burns. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015; 31:397–401.

Article12. Hastings H 2nd, Simmons BP. Hand fractures in children: a statistical analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984; 188:120–30.13. Barton NJ. Fractures of the phalanges of the hand in children. Hand. 1979; 11:134–43.

Article14. Kail RV. Children and their development. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc;2001.15. Mahabir RC, Kazemi AR, Cannon WG, Courtemanche DJ. Pediatric hand fractures: a review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001; 17:153–6.

Article16. Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BM. Nelson textbook of pediatrics e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences;2007.17. Valencia J, Leyva F, Gomez-Bajo GJ. Pediatric hand trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005; 432:77–86.

Article18. Vadivelu R, Dias JJ, Burke FD, Stanton J. Hand injuries in children: a prospective study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006; 26:29–35.19. Cha SM, Shin HD, Kim YK, Kim SG. Finger injuries by eyebrow razor blades in infants. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2023; 42:80–5.

Article20. Aman M, Zimmermann KS, Boecker AH, et al. Peripheral nerve injuries in children-prevalence, mechanisms and concomitant injuries: a major trauma center’s experience. Eur J Med Res. 2023; 28:116.

Article21. Sozbilen MC, Dastan AE, Gunay H, Kucuk L. One-year prospective analysis of hand and forearm injuries in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2021; 30:364–70.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pediatric Hand Trauma: An Analysis of 3,432 Pediatric Hand Trauma Cases Over 15 Years

- Analysis of 344 Hand Injuries in a Pediatric Population

- ICECI Based External Causes Analysis of Severe Pediatric Injury

- Clinical Analysis of Zone 5 Wrist Lacerations

- Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury : The Epidemiology in Korea