Nutr Res Pract.

2024 Jun;18(3):412-424. 10.4162/nrp.2024.18.3.412.

Iodine intake from brown seaweed and the related nutritional risk assessment in Koreans

- Affiliations

-

- 1Research Institute of Human Ecology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea

- 2Nutrition and Functional Food Research Division, National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation, Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Cheongju 28159, Korea

- 3Department of Food and Nutrition, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea

- KMID: 2558513

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2024.18.3.412

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Although iodine is essential for thyroid hormone production and controls many metabolic processes, there are few reports on the iodine intake of the population because of the scarcity of information on the iodine content in food. This study estimated the iodine intake of Koreans from brown seaweed, the major source of iodine in nature.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

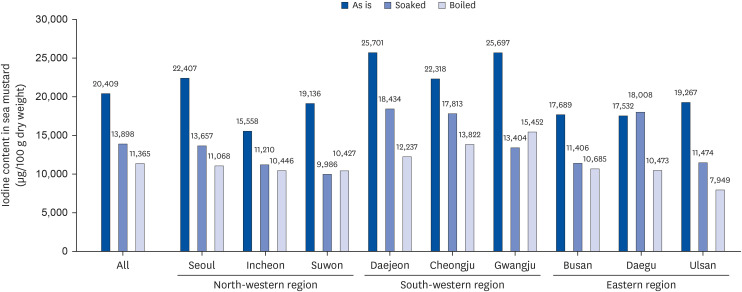

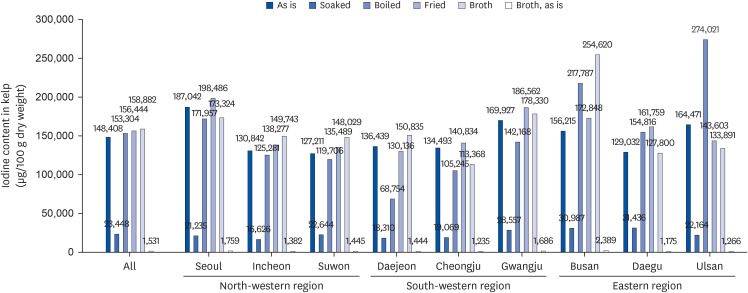

The dietary intake data from the recent Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2016–2021) and the iodine content in brown seaweed were used for the estimation. Nationwide brown seaweed samples were collected and prepared using the representative preparation/cooking methods in the Koreans’ diet before iodine analysis by alkaline digestion followed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry.

RESULTS

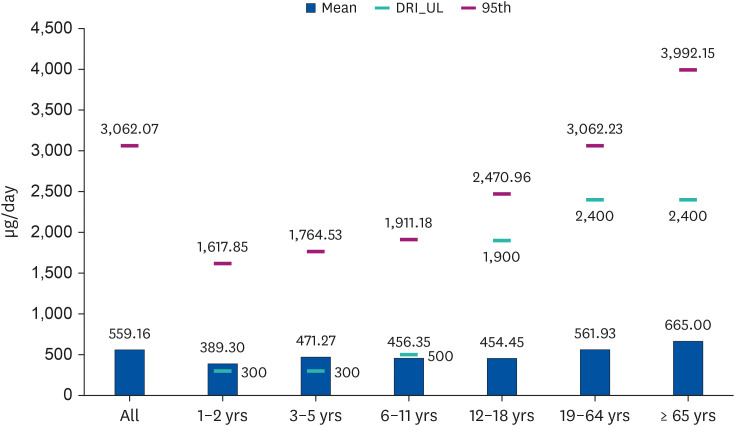

The mean (± SE) iodine intake from sea mustard was 96.01 ± 2.36 µg/day in the Korean population. Although the iodine content in kelp was approximately seven times higher than that in sea mustard, the mean iodine intake from kelp (except broth) was similar to that of sea mustard, 115.58 ± 7.71 µg/day, whereas that from kelp broth was 347.57 ± 10.03 µg/day. The overall mean iodine intake from brown seaweed was 559.16 ± 13.15 µg/day, well over the Recommended Nutrient Intake of iodine for Koreans. Nevertheless, the median intake was zero because only 37.6% of the population consumed brown seaweed on the survey date, suggesting that Koreans do not consume brown seaweed daily.

CONCLUSION

The distribution of the usual intake of iodine from brown seaweed in Koreans would be much tighter, resulting in a lower proportion of people exceeding the tolerable upper intake levels and possibly a lower mean intake than this study presented. Further study evaluating the iodine nutriture of Koreans based on the usual intake is warranted. Nevertheless, this study adds to the few reports on the iodine nutriture of Koreans.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (ICCIDD). Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination: a guide for programme managers. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO;2007. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241595827.2. Bundesinstitut fÜr Risikobewertung (BfR). Iodine intake in Germany on the decline again - tips for a good iodine intake. Questions and answers on iodine intake and the prevention of iodine deficiency. BfR FAQ of 20 February 2020 (updated 09 February 2021). BfR;2021. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/349/iodine-intake-in-germany-on-the-decline-again-tips-for-a-good-iodine-intake.pdf.3. Ittermann T, Albrecht D, Arohonka P, Bilek R, de Castro JJ, Dahl L, Filipsson Nystrom H, Gaberscek S, Garcia-Fuentes E, Gheorghiu ML, et al. Standardized map of iodine status in Europe. Thyroid. 2020; 30:1346–1354. PMID: 32460688.4. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 2020. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2020. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10904750/000586553.pdf[1].5. Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW). Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans 2020. Sejong: MOHW;2020.6. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand including recommended dietary intakes. Canberra: NHMRC;2006. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nutrient-reference-values-australia-and-new-zealand-including-recommended-dietary-intakes#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1.7. Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on the Definition of Dietary Fiber and the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intakes Proposed Definition of Dietary Fiber. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press;2001.8. Li Y, Wang J, Liu X, Li W, Mao D, Lu J, Li X, Tan H, Liu Y, Yan J, et al. Re-exploring the requirement of dietary iodine intake in Chinese female adults based on ‘iodine overflow theory’. Eur J Nutr. 2023; 62:1467–1478. PMID: 36651989.9. Lee J, Yeoh Y, Seo MJ, Lee GH, Kim C-i. Estimation of dietary iodine intake of Koreans through a Total Diet Study (TDS). Korean J Community Nutr. 2021; 26:48–55.10. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, Chun C, Khang YH, Oh K. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69–77. PMID: 24585853.11. Kim C-i, Lee J, Kwon S, Yoon HJ. Total Diet Study: for a closer-to-real estimate of dietary exposure to chemical substances. Toxicol Res. 2015; 31:227–240. PMID: 26483882.12. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Guide for Sample Preparation for the Korean Total Diet Study. Cheongju: MFDS;2017.13. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Food Code (No. 2021-54, Jun 29, 2021). Cheongju: MFDS;2021. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/brd/m_15/view.do?seq=72437.14. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS). Report on the Korean Total Diet Study (TDS): 2nd year. Cheongju: MFDS;2019.15. Ishizuki Y, Yamauchi K, Miura Y. Transient thyrotoxicosis induced by Japanese kombu. Nippon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi. 1989; 65:91–98. PMID: 2744193.16. Zava TT, Zava DT. Assessment of Japanese iodine intake based on seaweed consumption in Japan: a literature-based analysis. Thyroid Res. 2011; 4:14. PMID: 21975053.17. Nagataki S. The average of dietary iodine intake due to the ingestion of seaweeds is 1.2 mg/day in Japan. Thyroid. 2008; 18:667–668. PMID: 18578621.18. Bundesinstitut fÜr Risikobewertung (BfR). Health risks linked to high iodine levels in dried algae. BfR Opinion No. 026/2007. Berlin: BfR;2007. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/349/health_risks_linked_to_high_iodine_levels_in_dried_algae.pdf.19. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: A Risk Assessment Model for Establishing Upper Intake Levels for Nutrients. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press;1998. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/openbook/0309063485/html/.20. Kim HI, Oh HK, Park SY, Jang HW, Shin MH, Kim SW, Kim TH, Chung JH. Urinary iodine concentration and thyroid hormones: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2015. Eur J Nutr. 2019; 58:233–240. PMID: 29188371.21. The Iodine Global Network. Global Scorecard of Iodine Nutrition in 2021. Ottawa: The Iodine Global Network;2021. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://ign.org/app/uploads/2023/04/IGN_Global_Scorecard_2021_7_May_2021.pdf.22. World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (ICCIDD). Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination: a guide for programme managers. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO;2001. cited 2024 March 11. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/61278.23. Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Micronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press;2001.24. Kang MJ, Hwang IT, Chung HR. Excessive iodine intake and subclinical hypothyroidism in children and adolescents aged 6-19 years: results of the Sixth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013-2015. Thyroid. 2018; 28:773–779. PMID: 29737233.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Iodine Intake and Tolerable Upper Intake Level of Iodine for Koreans

- Dietary iodine intake and urinary iodine excretion in normal Korean adults

- Alterations of the TSH Levels in the Breast Feeding Newborn Infants after the Mother's Eating Brown Seaweed Soup

- Dietary iodine intake and urinary iodine excretion in patients with thyroid diseases

- Status of Iodine Intake and Comparison of Characteristics according to Iodine-sourced Food Intake Patterns of Chinese Adults: A Study Encompassing Three Regions with Different Iodine Nutritional Statuses