Intest Res.

2024 Jul;22(3):319-335. 10.5217/ir.2023.00071.

Association between oral corticosteroid starting dose and the incidence of pneumonia in Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis: a nation-wide claims database study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Toho University Sakura Medical Center, Sakura, Japan

- 2Medical Affairs, Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Tokyo, Japan

- KMID: 2558192

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2023.00071

Abstract

- Background/Aims

A previous study demonstrated that half of patients started oral corticosteroids (OCS) for ulcerative colitis (UC) exacerbations at lower doses than recommended by Japanese treatment guidelines (initial OCS prednisolone equivalent dose, 30–40 mg). This may relate to physician’s concern about infection, especially pneumonia including Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP), from high OCS doses. We assessed whether pneumonia incidence is increased with guideline-recommended OCS initial doses.

Methods

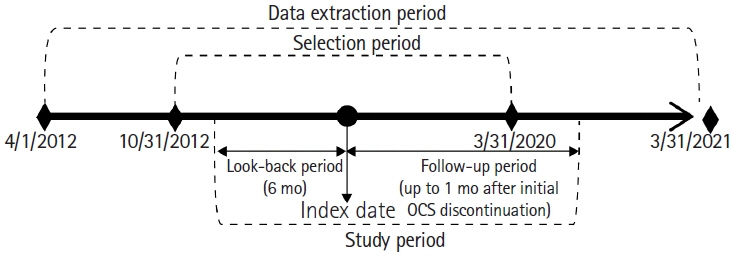

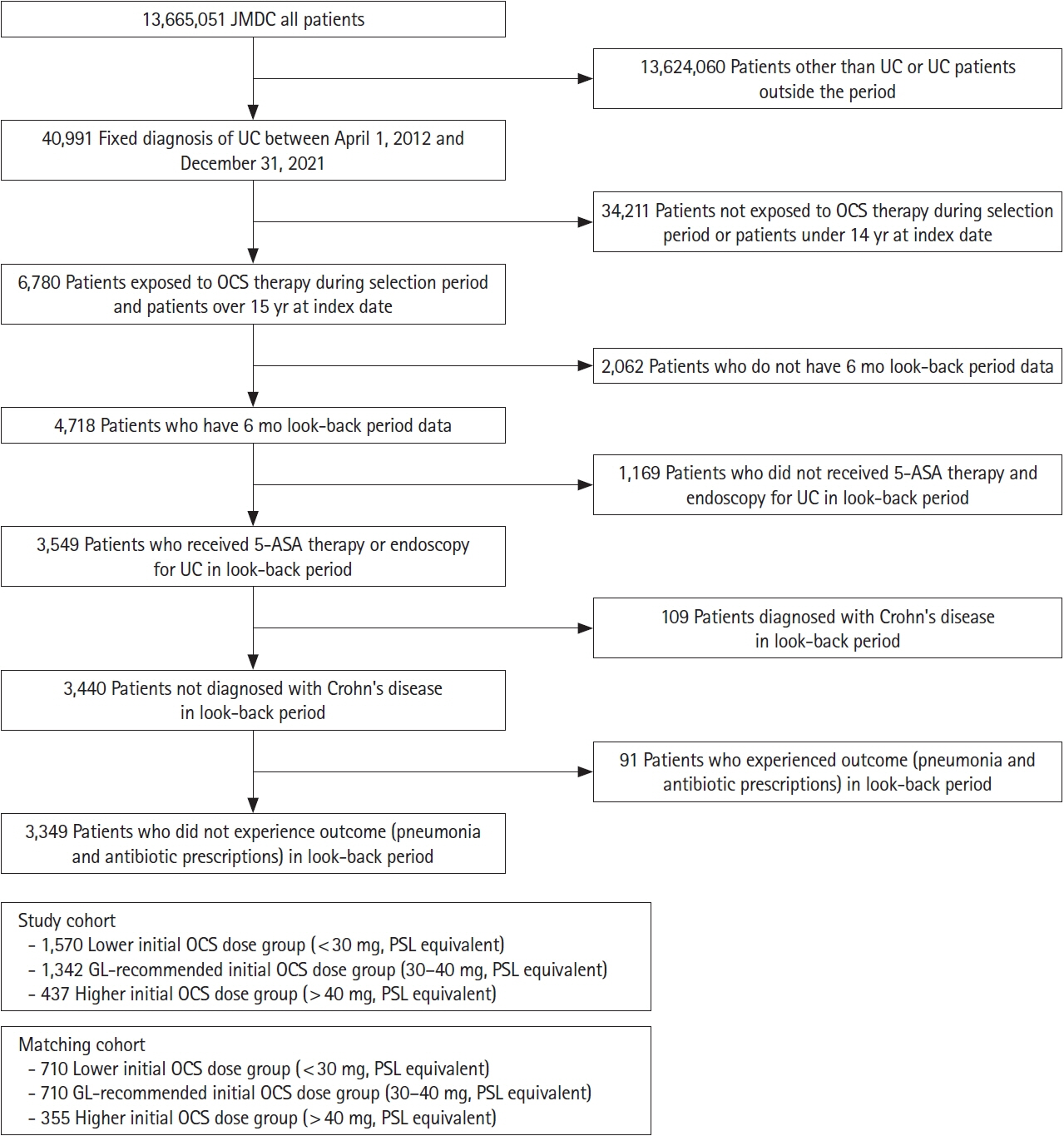

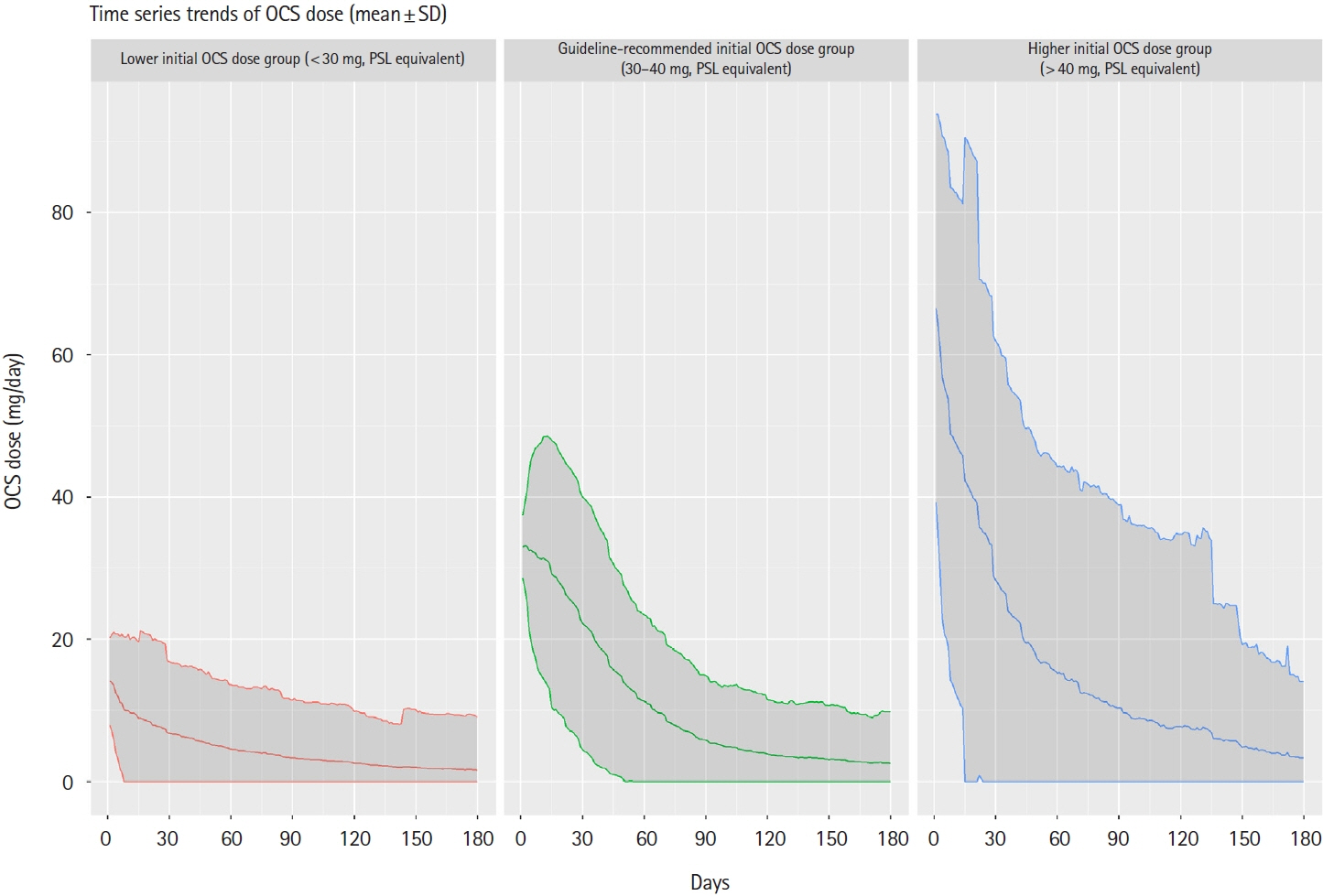

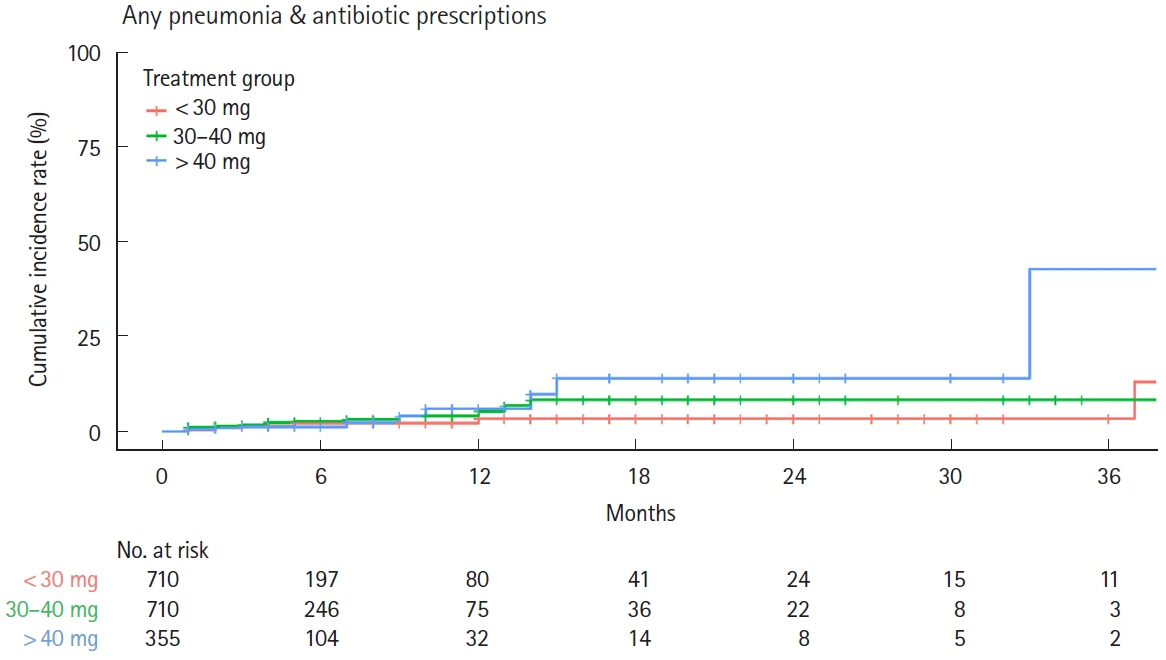

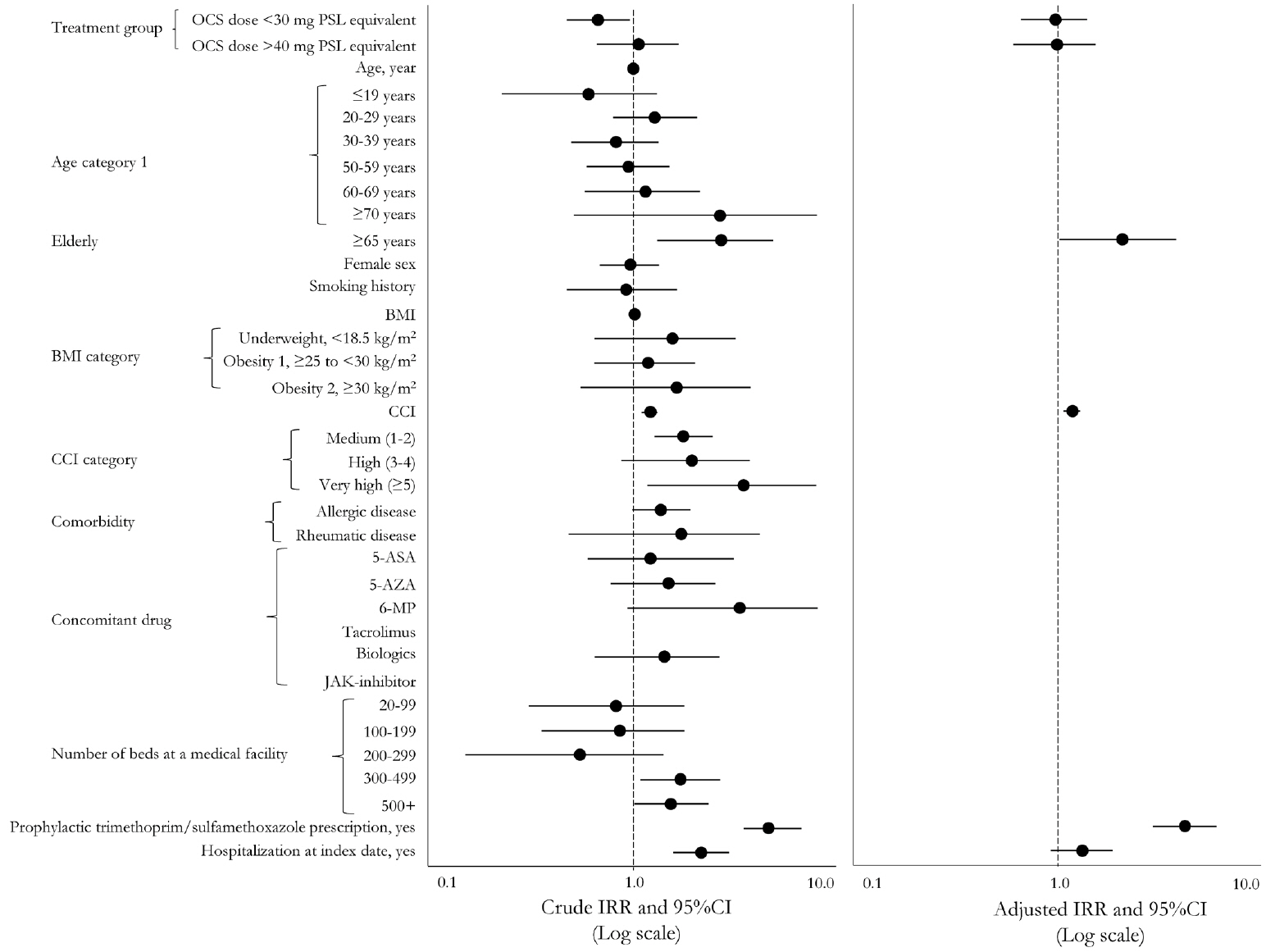

This retrospective cohort study used the Japan Medical Data Center claims database (2012–2021). The whole cohort consisted of all UC patients who started OCS during the study period meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The matched cohort was created by propensity score matching; the lower (initial OCS dose < 30 mg), guideline-recommended (30–40 mg), and higher groups ( > 40 mg) in a 2:2:1 ratio. Pneumonia incidence in the primary analysis was evaluated in the matched cohort. A Poisson regression model determined pneumonia-related risk factors in the whole cohort.

Results

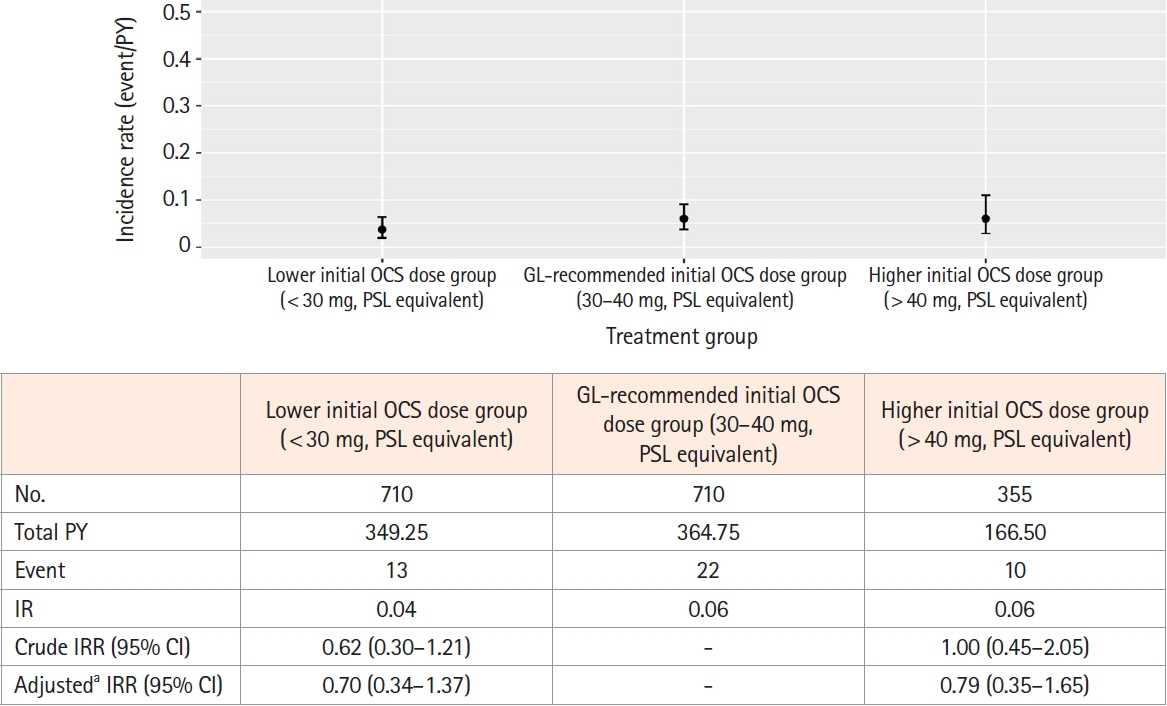

After screening, 3,349 patients comprised the whole cohort; 1,775 patients comprised the matched cohort (lower dose, n = 710; guideline-recommended dose, n = 710; higher dose, n = 355). The incidence of any pneumonia was low; no differences were observed in incidence rates across these dose subgroups. In total, 3 PJP cases were found in the whole cohort, but not detected in the matched cohort. Several risk factors for any pneumonia were identified, including age, higher comorbidities index, treatment in large facility and hospitalization.

Conclusions

The incidence of pneumonia, including PJP, in UC patients was low across initial OCS dose treatment subgroups.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012; 380:1606–1619.

Article2. Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018; 53:305–353.

Article3. Okayasu M, Ogata H, Yoshiyama Y. Use of corticosteroids for remission induction therapy in patients with new-onset ulcerative colitis in real-world settings. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019; 7:1565889.

Article4. Suzuki Y, Nawata H, Soen S, et al. Guidelines on the management and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research: 2014 update. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014; 32:337–350.5. Nakase H, Uchino M, Shinzaki S, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021; 56:489–526.

Article6. Matsuoka K, Igarashi A, Sato N, et al. Trends in corticosteroid prescriptions for ulcerative colitis and factors associated with long-term corticosteroid use: analysis using Japanese claims data from 2006 to 2016. J Crohns Colitis. 2021; 15:358–366.

Article7. Miyazaki C, Sakashita T, Jung W, Kato S. Real-world prescription pattern and healthcare cost among patients with ulcerative colitis in Japan: a retrospective claims data analysis. Adv Ther. 2021; 38:2229–2247.

Article8. Long MD, Martin C, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Increased risk of pneumonia among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013; 108:240–248.

Article9. Kojima K, Sato T, Uchino M, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia during immunosuppressive treatment in patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020; 29:167–173.

Article10. Schimmer BP, Funder JW. ACTH, adrenal steroids, and pharmacology of the adrenal cortex. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2011.11. Kimura S, Sato T, Ikeda S, Noda M, Nakayama T. Development of a database of health insurance claims: standardization of disease classifications and anonymous record linkage. J Epidemiol. 2010; 20:413–419.

Article12. Asakura K, Nishiwaki Y, Inoue N, Hibi T, Watanabe M, Takebayashi T. Prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2009; 44:659–665.

Article13. Shi HY, Chan FK, Leung WK, et al. Natural history of elderlyonset ulcerative colitis: results from a territory-wide inflammatory bowel disease registry. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:176–185.

Article14. Takahashi H, Matsui T, Hisabe T, et al. Second peak in the distribution of age at onset of ulcerative colitis in relation to smoking cessation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 29:1603–1608.

Article15. Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG. Inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly is associated with worse outcomes: a national study of hospitalizations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009; 15:182–189.

Article16. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005; 43:1130–1139.

Article17. Masuda M, Fukata N, Sano Y, et al. Analysis of the initial dose and reduction rate of corticosteroid for ulcerative colitis in clinical practice. JGH Open. 2022; 6:612–620.

Article18. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:699–710.

Article19. Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Gibson PR, et al. Continuous clinical response is associated with a change of disease course in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis treated with golimumab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019; 25:163–171.

Article20. Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:2462–2476.

Article21. Sandborn WJ, Su C, Panes J. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:496–497.

Article22. Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012; 142:257–265.

Article23. Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1201–1214.

Article24. Higashiyama M, Sugita A, Koganei K, et al. Management of elderly ulcerative colitis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2019; 54:571–586.

Article25. Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022; 16:2–17.

Article26. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European evidencebased consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: part 1. Diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017; 11:3–25.

Article27. Llaó J, Naves JE, Ruiz-Cerulla A, et al. Intravenous corticosteroids in moderately active ulcerative colitis refractory to oral corticosteroids. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:1523–1528.

Article28. Fillatre P, Decaux O, Jouneau S, et al. Incidence of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia among groups at risk in HIV-negative patients. Am J Med. 2014; 127:1242.

Article29. Yoshida A, Kamata N, Yamada A, et al. Risk factors for mortality in Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2019; 3:167–172.

Article30. Okafor PN, Nunes DP, Farraye FA. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in inflammatory bowel disease: when should prophylaxis be considered? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:1764–1771.31. Rahier JF, Magro F, Abreu C, et al. Second European evidencebased consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:443–468.

Article32. Cotter TG, Gathaiya N, Catania J, et al. Low risk of pneumonia from Pneumocystis jirovecii infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving immune suppression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 15:850–856.

Article33. Akerkar GA, Peppercorn MA, Hamel MB, Parker RA. Corticosteroid-associated complications in elderly Crohn’s disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997; 92:461–464.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Cytomegalvirus Colitis Developed during the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis

- Patterns of Ulcerative Colitis Treatments and Factors Affecting the Prescribing of Systemic Corticosteroid using Health Insurance Claims Database

- Recurrent Eosinophilic Pneumonia Associated with Mesalazine Suppository in a Patient with Ulcerative Colitis

- Trends in the incidence of ulcerative colitis in Korea

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis