Diabetes Metab J.

2024 Jul;48(4):790-801. 10.4093/dmj.2023.0298.

Enhancing Diabetes Care through a Mobile Application: A Randomized Clinical Trial on Integrating Physical and Mental Health among Disadvantaged Individuals

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea

- 3Sanofi-Aventis Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University Medical Center, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 6WiseMi Psychology Institute, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2558046

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2023.0298

Abstract

- Background

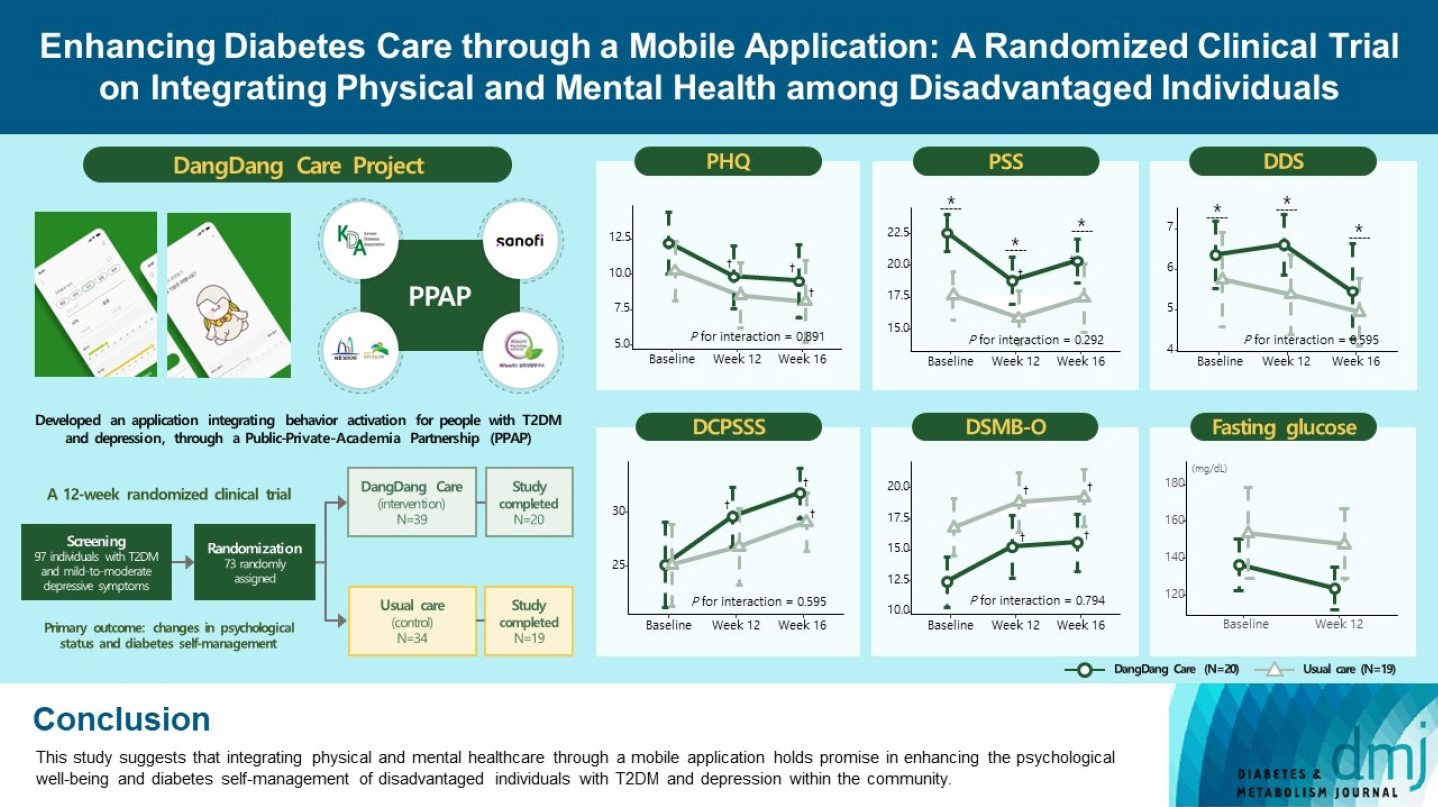

This study examines integrating physical and mental healthcare for disadvantaged persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus and mild-to-moderate depression in the community, using a mobile application within a public-private-academic partnership.

Methods

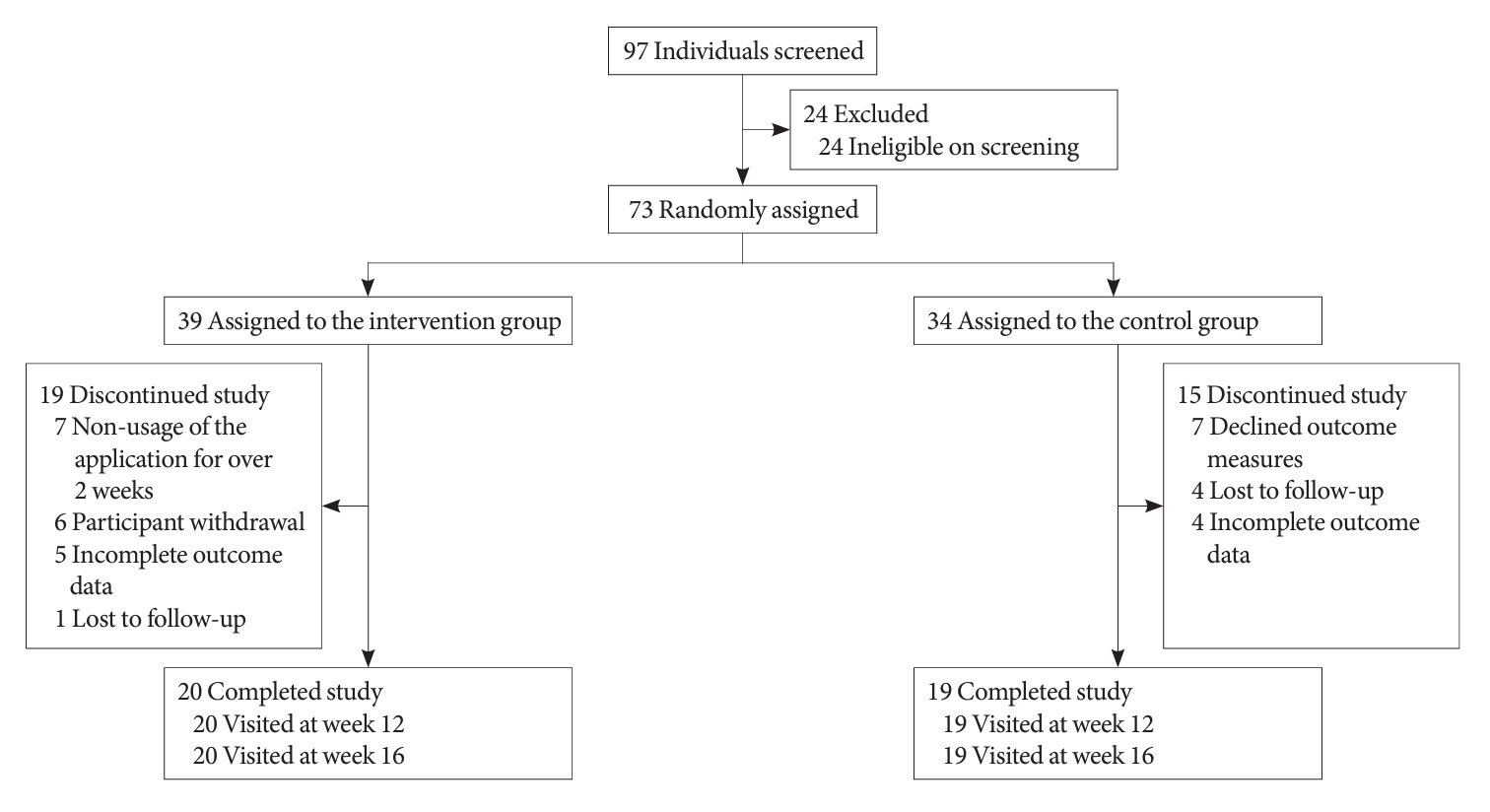

The Korean Diabetes Association has developed a mobile application combining behavioral activation for psychological well-being and diabetes self-management, with conventional medical therapy. Participants were randomly assigned to receive the application with usual care or only usual care. Primary outcomes measured changes in psychological status and diabetes selfmanagement through questionnaires at week 12 from the baseline. Secondary outcomes assessed glycemic and lipid control, with psychological assessments at week 16.

Results

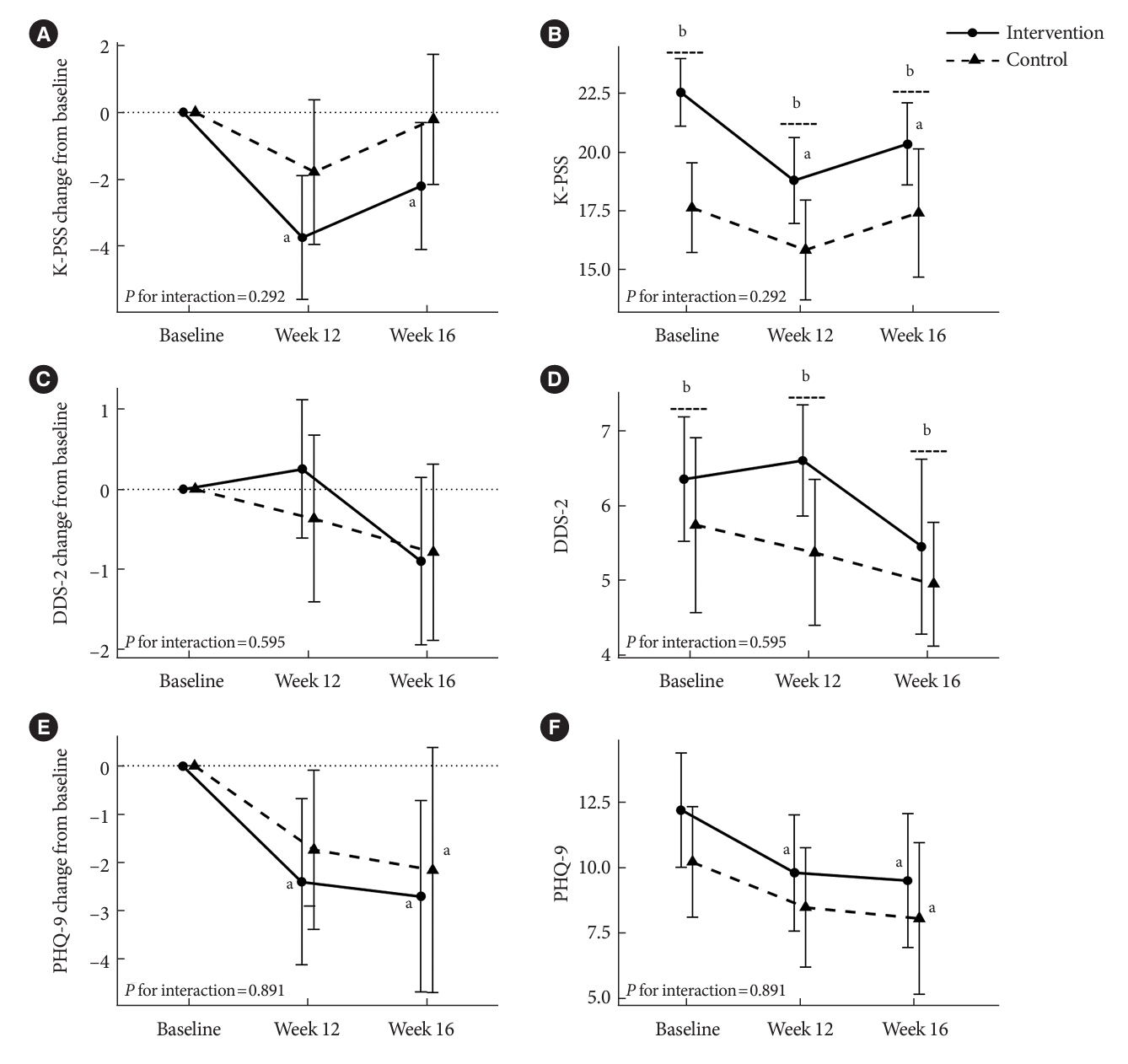

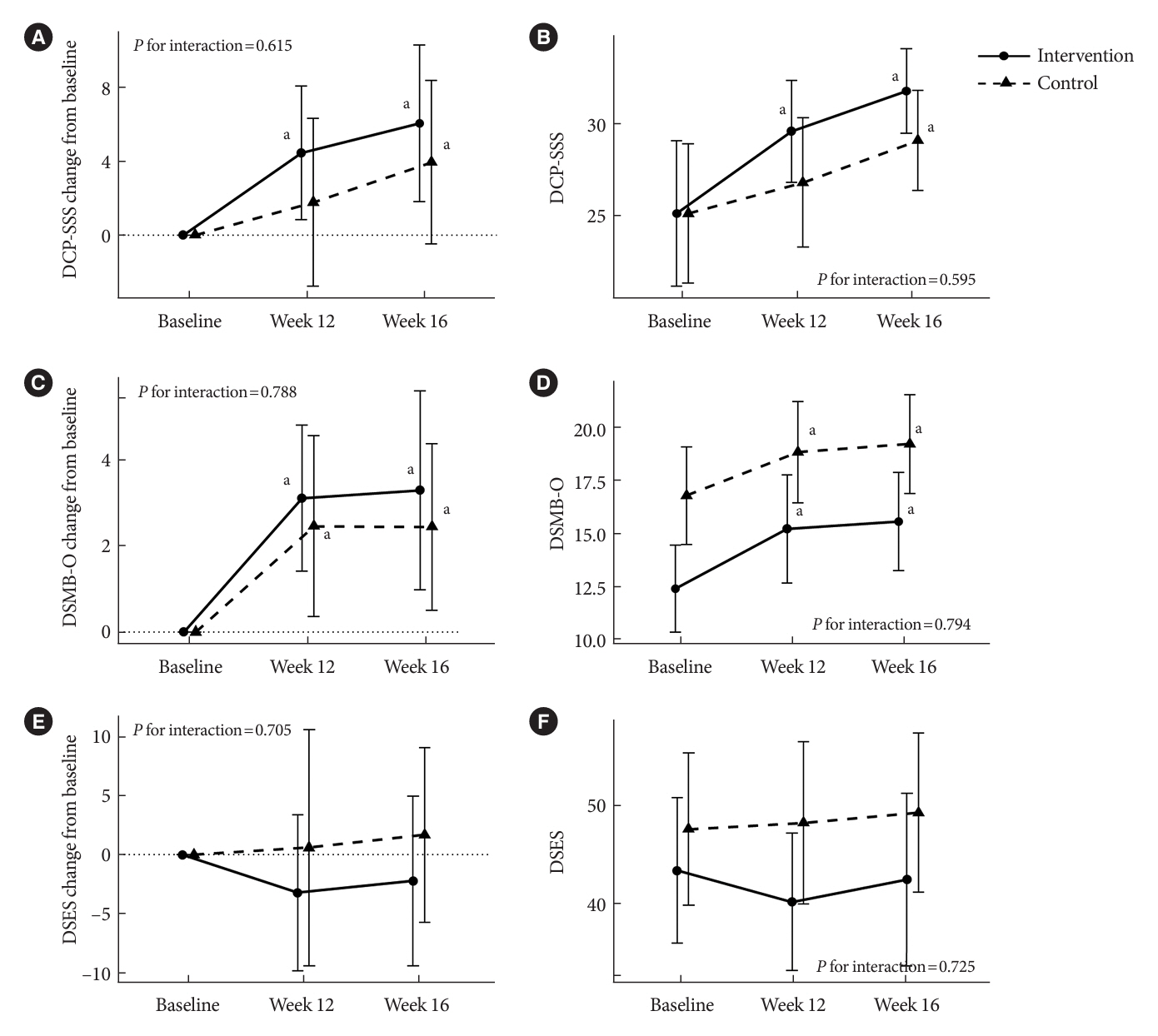

Thirty-nine of 73 participants completed the study (20 and 19 in the intervention and control groups, respectively) and were included in the analysis. At week 12, the intervention group showed significant reductions in depression severity and perceived stress compared to the control group. Additionally, they reported increased perceived social support and demonstrated improved diabetes self-care behavior. These positive effects persisted through week 16, with the added benefit of reduced anxiety. While fasting glucose levels in the intervention group tended to improve, no other significant differences were observed in laboratory assessments between the groups.

Conclusion

This study provides compelling evidence for the potential efficacy of a mobile application that integrates physical and mental health components to address depressive symptoms and enhance diabetes self-management in disadvantaged individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression. Further research involving larger and more diverse populations is warranted to validate these findings and solidify their implications.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Bae JH, Han KD, Ko SH, Yang YS, Choi JH, Choi KM, et al. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2021. Diabetes Metab J. 2022; 46:417–26.2. Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018; 14:88–98.

Article3. Holt RI, Mitchell AJ. Diabetes mellitus and severe mental illness: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015; 11:79–89.

Article4. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015; 72:334–41.

Article5. Goldfarb M, De Hert M, Detraux J, Di Palo K, Munir H, Music S, et al. Severe mental illness and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022; 80:918–33.6. Momen NC, Plana-Ripoll O, Agerbo E, Benros ME, Borglum AD, Christensen MK, et al. Association between mental disorders and subsequent medical conditions. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1721–31.7. Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, Holtz Y, Erlangsen A, Canudas-Romo V, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019; 394:1827–35.

Article8. Fleetwood KJ, Wild SH, Licence KA, Mercer SW, Smith DJ, Jackson CA, et al. Severe mental illness and type 2 diabetes outcomes and complications: a nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2023; 46:1363–71.

Article9. Ko SH, Bae JH, Yang YS, Choi JH, Han KD, Kwon HS. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2022. Seoul: Korean Diabetes Association;2022.10. World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization;2016.11. Jung JH, Lee JH; Camp Committee. The effects of the 2030 Diabetes Camp Program on depression, anxiety, and stress in diabetic patients. J Korean Diabetes. 2019; 20:194–204.

Article12. Carethers JM. Rectifying COVID-19 disparities with treatment and vaccination. JCI Insight. 2021; 6:e147800.13. Richards DA, Ekers D, McMillan D, Taylor RS, Byford S, Warren FC, et al. Cost and Outcome of Behavioural Activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016; 388:871–80.

Article14. Cummings DM, Lutes LD, Littlewood K, Solar C, Carraway M, Kirian K, et al. Randomized trial of a tailored cognitive behavioral intervention in type 2 diabetes with comorbid depressive and/or regimen-related distress symptoms: 12-month outcomes from COMRADE. Diabetes Care. 2019; 42:841–8.

Article15. Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Hopko SD. A brief behavioral activation treatment for depression. Treatment manual. Behav Modif. 2001; 25:255–86.

Article16. Kazantzis N, Reinecke MA, Freeman A. Cognitive and behavioral theories in clinical practice. New York: The Guilford Press;Chapter 6, Behavioral activation therapy. 2010. p. 193–217.17. Butcher NJ, Monsour A, Mew EJ, Chan AW, Moher D, MayoWilson E, et al. Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial reports: the CONSORT-outcomes 2022 extension. JAMA. 2022; 328:2252–64.18. Magkos F, Hjorth MF, Astrup A. Diet and exercise in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020; 16:545–55.

Article19. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023; 46(Supple 1):S68–96.20. Denee TR, Sneekes A, Stolk P, Juliens A, Raaijmakers JA, Goldman M, et al. Measuring the value of public-private partnerships in the pharmaceutical sciences. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012; 11:419.

Article21. Seiglie JA, Nambiar D, Beran D, Miranda JJ. To tackle diabetes, science and health systems must take into account social context. Nat Med. 2021; 27:193–5.

Article22. Lund C, Brooke-Sumner C, Baingana F, Baron EC, Breuer E, Chandra P, et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the sustainable development goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018; 5:357–69.23. Marmot M, Bell R. Social determinants and non-communicable diseases: time for integrated action. BMJ. 2019; 364:l251.

Article24. Belanger MJ, Hill MA, Angelidi AM, Dalamaga M, Sowers JR, Mantzoros CS. COVID-19 and disparities in nutrition and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:e69.

Article25. Myers BA, Klingensmith R, de Groot M. Emotional correlates of the COVID-19 pandemic in individuals with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022; 45:42–58.

Article26. Chao AM, Wadden TA, Clark JM, Hayden KM, Howard MJ, Johnson KC, et al. Changes in the prevalence of symptoms of depression, loneliness, and insomnia in U.S. older adults with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Look AHEAD Study. Diabetes Care. 2022; 45:74–82.

Article27. Distaso W, Malik MM, Semere S, AlHakami A, Alexander EC, Hirani D, et al. Diabetes self-management during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associations with COVID-19 anxiety syndrome, depression and health anxiety. Diabet Med. 2022; 39:e14911.28. Kremers SH, Wild SH, Elders PJ, Beulens JW, Campbell DJ, Pouwer F, et al. The role of mental disorders in precision medicine for diabetes: a narrative review. Diabetologia. 2022; 65:1895–906.

Article29. Hou C, Carter B, Hewitt J, Francisa T, Mayor S. Do mobile phone applications improve glycemic control (HbA1c) in the self-management of diabetes?: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE of 14 randomized trials. Diabetes Care. 2016; 39:2089–95.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Diabetes Management via a Mobile Application: a Case Report

- HealthTWITTER Initiative: Design of a Social Networking Service Based Tailored Application for Diabetes Self-Management

- Development and Evaluation of Health Care Providers' Counseling Manual in Mobile Application for Lifelong Health Care among Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B

- Website and Mobile Application-Based Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults with Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Improving Diabetes Self-Mangement and Mental Health through Acceptance and Commitment Therapy