Diabetes Metab J.

2024 Jul;48(4):780-789. 10.4093/dmj.2023.0335.

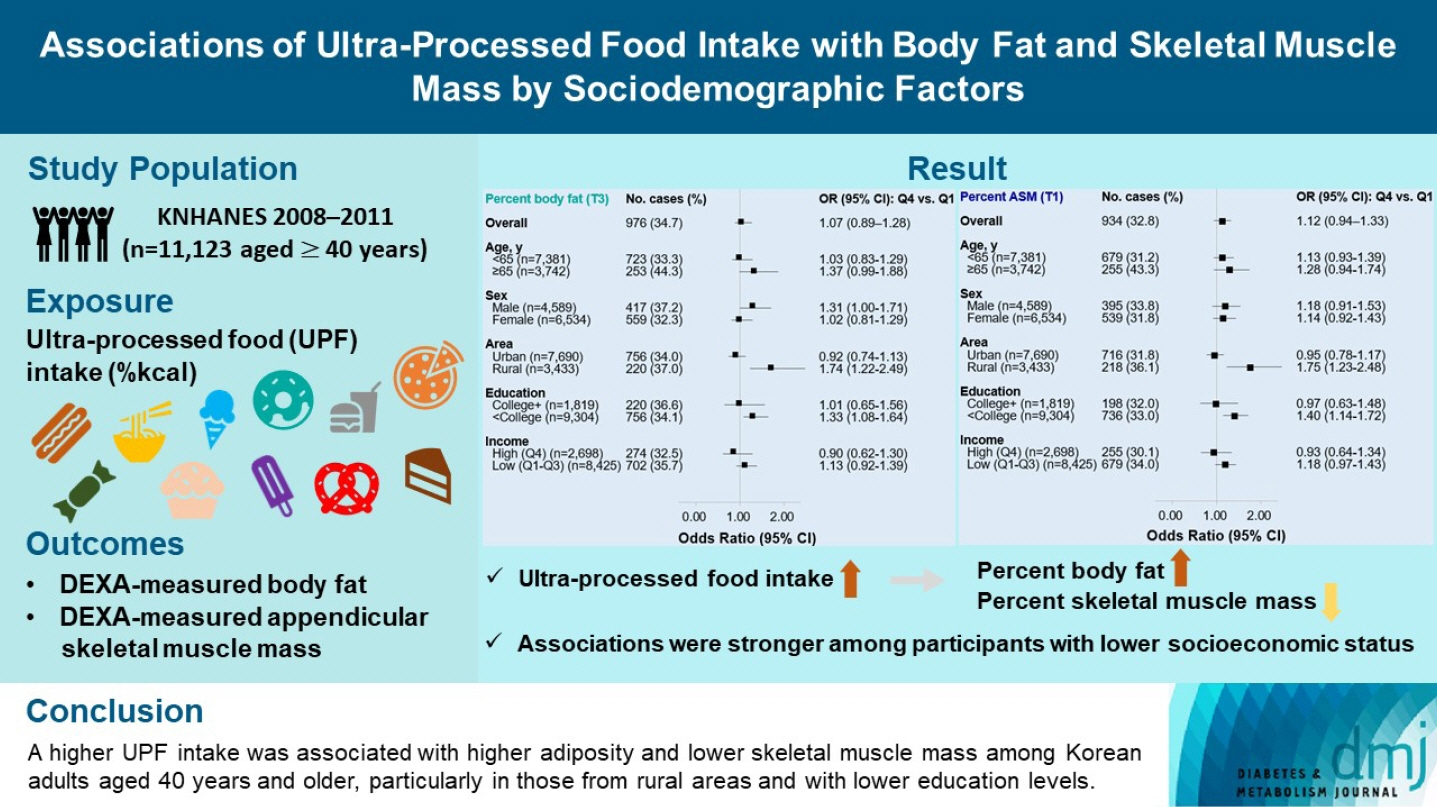

Associations of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with Body Fat and Skeletal Muscle Mass by Sociodemographic Factors

- Affiliations

-

- 1Biomedical Research Institute, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea

- 2National Food Safety Information Service, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea

- 4The Korean Institute of Nutrition, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea

- KMID: 2558045

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2023.0335

Abstract

- Background

The effects of excessive ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption on body composition measures or sociodemographic disparities are understudied in Korea. We aimed to investigate the association of UPF intake with percent body fat (PBF) and percent appendicular skeletal muscle mass (PASM) by sociodemographic status in adults.

Methods

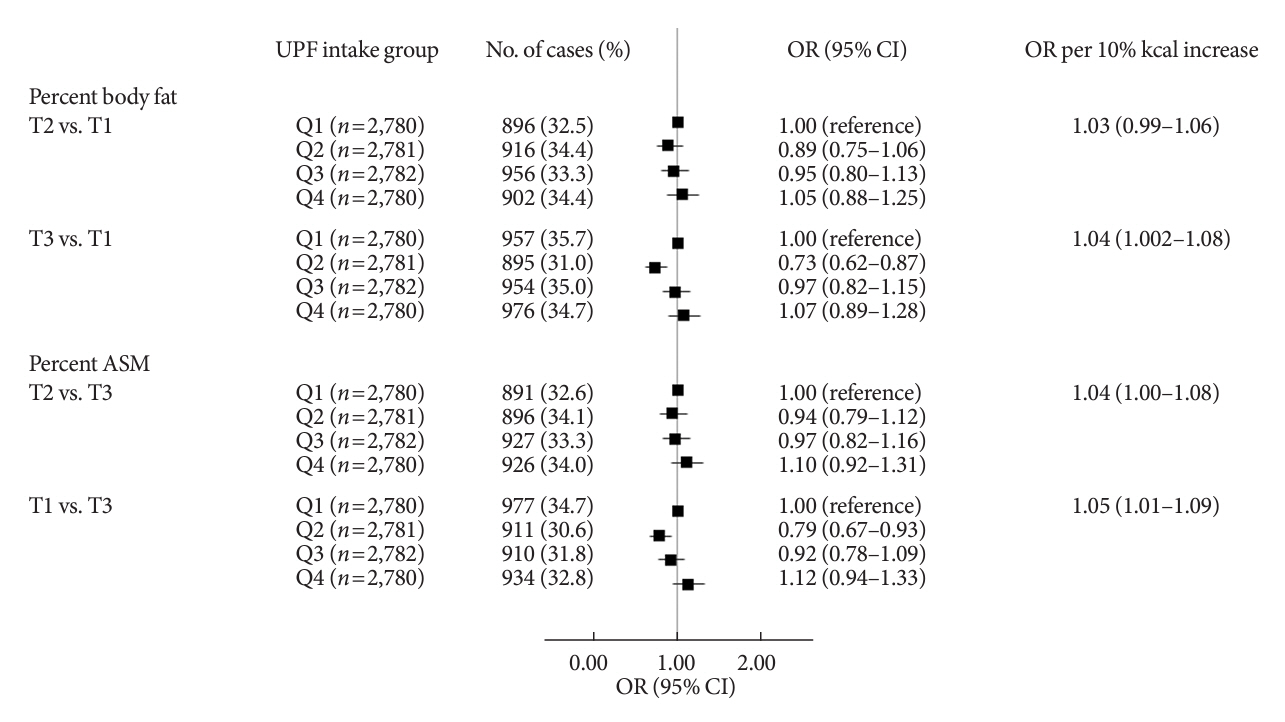

This study used data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2011 (n=11,123 aged ≥40 years). We used a NOVA system to classify all foods reported in a 24-hour dietary recall, and the percentage of energy intake (%kcal) from UPFs was estimated. PBF and PASM were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Tertile (T) 3 of PBF indicated adiposity and T1 of PASM indicated low skeletal muscle mass, respectively. Multinomial logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) after adjusting covariates.

Results

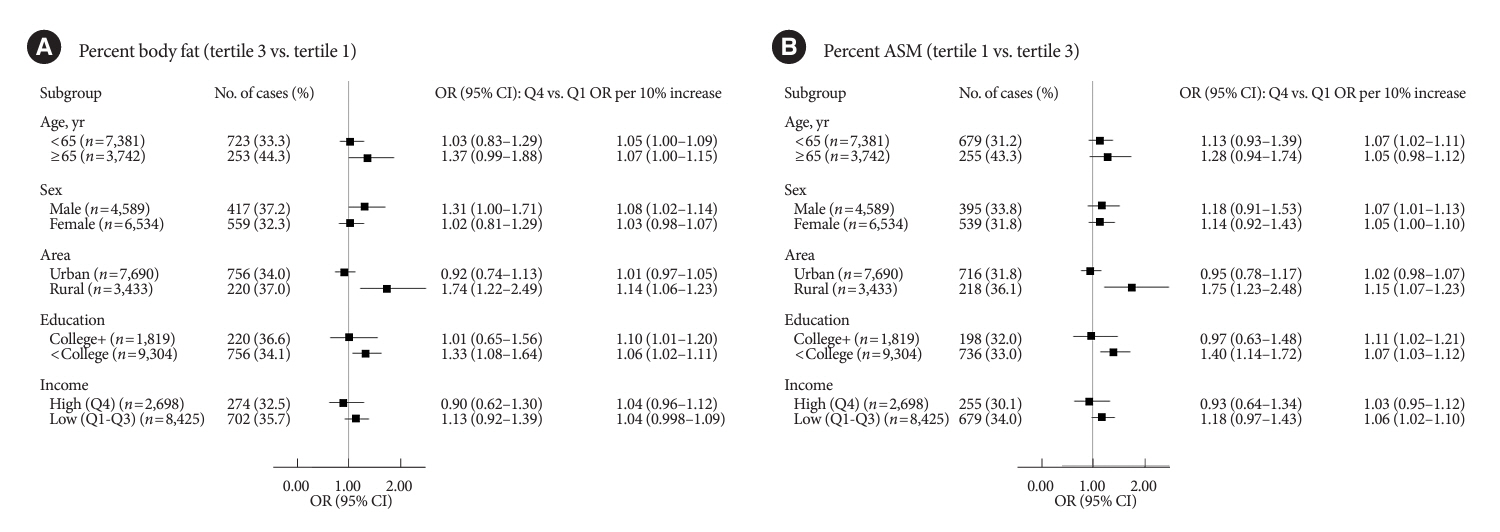

UPF intake was positively associated with PBF-defined adiposity (ORper 10% increase, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.002 to 1.08) and low PASM (ORper 10% increase, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.09). These associations were stronger in rural residents (PBF: ORper 10% increase, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.23; PASM: ORper 10% increase, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.23) and not college graduates (PBF: ORper 10% increase, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.11; PASM: ORper 10% increase, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.12) than their counterparts.

Conclusion

A higher UPF intake was associated with higher adiposity and lower skeletal muscle mass among Korean adults aged 40 years and older, particularly in those from rural areas and with lower education levels.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Navigating Ultra-Processed Foods with Insight

Ji A Seo

Diabetes Metab J. 2024;48(4):713-715. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2024.0316.

Reference

-

1. GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396:1223–49.2. Yang YS, Han BD, Han K, Jung JH, Son JW; Taskforce Team of the Obesity Fact Sheet of the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. Obesity fact sheet in Korea, 2021: trends in obesity prevalence and obesity-related comorbidity incidence stratified by age from 2009 to 2019. J Obes Metab Syndr. 2022; 31:169–77.

Article3. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight fact sheet. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en (cited 2023 Nov 11).4. Ponti F, Santoro A, Mercatelli D, Gasperini C, Conte M, Martucci M, et al. Aging and imaging assessment of body composition: from fat to facts. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020; 10:861.

Article5. Neeland IJ, Ross R, Despres JP, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S, Shai I, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019; 7:715–25.6. Hemler EC, Hu FB. Plant-based diets for personal, population, and planetary health. Adv Nutr. 2019; 10(Suppl 4):S275–83.

Article7. Popkin BM, Ng SW. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes Rev. 2022; 23:e13366.

Article8. Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, et al. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019; 22:936–41.

Article9. Askari M, Heshmati J, Shahinfar H, Tripathi N, Daneshzad E. Ultra-processed food and the risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020; 44:2080–91.

Article10. Moradi S, Entezari MH, Mohammadi H, Jayedi A, Lazaridi AV, Kermani MA, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and adult obesity risk: a systematic review and dose-response metaanalysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023; 63:249–60.11. Konieczna J, Morey M, Abete I, Bes-Rastrollo M, Ruiz-Canela M, Vioque J, et al. Contribution of ultra-processed foods in visceral fat deposition and other adiposity indicators: prospective analysis nested in the PREDIMED-Plus trial. Clin Nutr. 2021; 40:4290–300.

Article12. Rudakoff LC, Magalhaes EI, Viola PC, de Oliveira BR, da Silva Coelho CC, Braganca ML, et al. Ultra-processed food consumption is associated with increase in fat mass and decrease in lean mass in Brazilian women: a cohort study. Front Nutr. 2022; 9:1006018.

Article13. Shim JS, Ha KH, Kim DJ, Kim HC. Diet quality partially mediates the association between ultraprocessed food consumption and adiposity indicators. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023; 31:2430–9.

Article14. Marron-Ponce JA, Sanchez-Pimienta TG, Louzada ML, Batis C. Energy contribution of NOVA food groups and sociodemographic determinants of ultra-processed food consumption in the Mexican population. Public Health Nutr. 2018; 21:87–93.

Article15. Baraldi LG, Martinez Steele E, Canella DS, Monteiro CA. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and associated sociodemographic factors in the USA between 2007 and 2012: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018; 8:e020574.16. Ozcariz SGI, Pudla KJ, Martins APB, Peres MA, Conzalez-Chica DA. Sociodemographic disparities in the consumption of ultra-processed food and drink products in Southern Brazil: a population-based study. J Public Health (Berl). 2019; 27:649–58.

Article17. Khandpur N, Cediel G, Obando DA, Jaime PC, Parra DC. Sociodemographic factors associated with the consumption of ultra-processed foods in Colombia. Rev Saude Publica. 2020; 54:19.

Article18. Shim JS, Shim SY, Cha HJ, Kim J, Kim HC. Socioeconomic characteristics and trends in the consumption of ultra-processed foods in Korea from 2010 to 2018. Nutrients. 2021; 13:1120.

Article19. Juul F, Parekh N, Martinez-Steele E, Monteiro CA, Chang VW. Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022; 115:211–21.

Article20. Jang HJ, Oh H. Trends and inequalities in overall and abdominal obesity by sociodemographic factors in Korean adults, 1998-2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18:4162.21. Rural Development Administration, National Institute of Agriculatural Sciences. Standard food composition table. 7th ed. Suwon: Rural development Administration, National Institute of Agriculatural Sciences;2006.22. Park HJ, Park S, Kim JY. Development of Korean NOVA Food Classification and estimation of ultra-processed food intake among adults: using 2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean J Community Nutr. 2022; 27:455–67.

Article23. Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010; 29:1037–57.

Article24. Valicente VM, Peng CH, Pacheco KN, Lin L, Kielb EI, Dawoodani E, et al. Ultraprocessed foods and obesity risk: a critical review of reported mechanisms. Adv Nutr. 2023; 14:718–38.

Article25. Prasad K, Dhar I. Oxidative stress as a mechanism of added sugar-induced cardiovascular disease. Int J Angiol. 2014; 23:217–26.

Article26. Kelli HM, Corrigan FE 3rd, Heinl RE, Dhindsa DS, Hammadah M, Samman-Tahhan A, et al. Relation of changes in body fat distribution to oxidative stress. Am J Cardiol. 2017; 120:2289–93.27. Park Y, Jang J, Lee D, Yoon M. Vitamin C inhibits visceral adipocyte hypertrophy and lowers blood glucose levels in high-fatdiet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice. Biomed Sci Lett. 2018; 24:311–8.

Article28. Han SF, Jiao J, Zhang W, Xu JY, Zhang W, Fu CL, et al. Lipolysis and thermogenesis in adipose tissues as new potential mechanisms for metabolic benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition. 2017; 33:118–24.

Article29. Yook JS, Thomas SS, Toney AM, You M, Kim YC, Liu Z, et al. Dietary iron deficiency modulates adipocyte iron homeostasis, adaptive thermogenesis, and obesity in C57BL/6 mice. J Nutr. 2021; 151:2967–75.

Article30. Forde CG, Mars M, de Graaf K. Ultra-processing or oral processing?: a role for energy density and eating rate in moderating energy intake from processed foods. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020; 4:nzaa019.

Article31. Crimarco A, Landry MJ, Gardner CD. Ultra-processed foods, weight gain, and co-morbidity risk. Curr Obes Rep. 2022; 11:80–92.32. Harb AA, Shechter A, Koch PA, St-Onge MP. Ultra-processed foods and the development of obesity in adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2023; 77:619–27.

Article33. Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, Cai H, Cassimatis T, Chen KY, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of Ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019; 30:67–77.

Article34. Zhang Z, Kahn HS, Jackson SL, Steele EM, Gillespie C, Yang Q. Associations between ultra- or minimally processed food intake and three adiposity indicators among US adults: NHANES 2011 to 2016. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022; 30:1887–97.35. Shim JS, Ha KH, Kim DJ, Kim HC. Ultra-processed food consumption and obesity in Korean adults. Diabetes Metab J. 2023; 47:547–58.

Article36. Jeong SM, Lee DH, Rezende LF, Giovannucci EL. Different correlation of body mass index with body fatness and obesity-related biomarker according to age, sex and race-ethnicity. Sci Rep. 2023; 13:3472.37. Carpenter CL, Yan E, Chen S, Hong K, Arechiga A, Kim WS, et al. Body fat and body-mass index among a multiethnic sample of college-age men and women. J Obes. 2013; 2013:790654.

Article38. Baspinar B, Guldas M. Traditional plain yogurt: a therapeutic food for metabolic syndrome? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021; 61:3129–43.

Article39. Akagawa S, Akagawa Y, Nakai Y, Yamagishi M, Yamanouchi S, Kimata T, et al. Fiber-rich barley increases butyric acid-producing bacteria in the human gut microbiota. Metabolites. 2021; 11:559.

Article40. Meadows AD, Swanson SA, Galligan TM, Naidenko OV, O’Connell N, Perrone-Gray S, et al. Packaged foods labeled as organic have a more healthful profile than their conventional counterparts, according to analysis of products sold in the U.S. in 2019-2020. Nutrients. 2021; 13:3020.

Article41. Zagorsky JL, Smith PK. The association between socioeconomic status and adult fast-food consumption in the U. S. Econ Hum Biol. 2017; 27(Pt A):12–25.42. Scrinis G, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and the limits of product reformulation. Public Health Nutr. 2018; 21:247–52.

Article43. Kim EK, Fenyi JO, Kim JH, Kim MH, Yean SE, Park KW, et al. Comparison of total energy intakes estimated by 24-hour diet recall with total energy expenditure measured by the doubly labeled water method in adults. Nutr Res Pract. 2022; 16:646–57.

Article44. Kye S, Kwon SO, Lee SY, Lee J, Kim BH, Suh HJ, et al. Underreporting of energy intake from 24-hour dietary recalls in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2014; 5:85–91.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of Muscle Mass Indexes According to Protein Intake in Obese Patients

- Development of Korean NOVA Food Classification and Estimation of Ultra-Processed Food Intake Among Adults: Using 2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- The Level of Serum Cholesterol is Negatively Associated with Lean Body Mass in Korean non-Diabetic Cancer Patients

- Total energy intake according to the level of skeletal muscle mass in Korean adults aged 30 years and older: an analysis of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES) 2008–2011

- Association between energy intake and skeletal muscle mass according to dietary patterns derived by cluster analysis: data from the 2008 ~ 2010 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey