J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Jul;39(25):e192. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e192.

Association Between Economic Activity and Depressive Symptoms Among Women With Parenting Children

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Health Policy Management, Graduate School of Public Health, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Institute of Health Services Research, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Public Health, Graduate School, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Policy Analysis and Management, College of Human Ecology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

- KMID: 2557769

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e192

Abstract

- Background

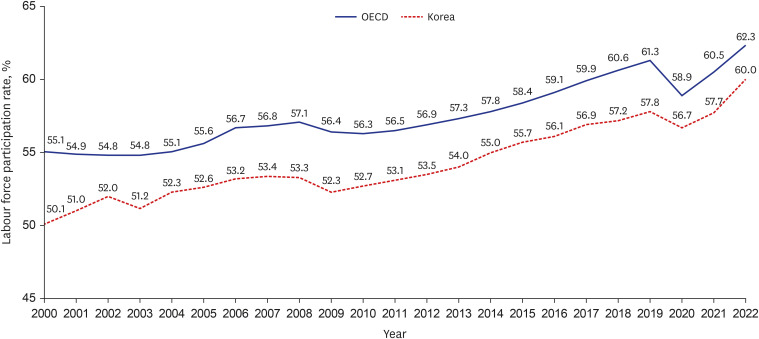

Balancing parenting and work life poses challenges for women with children, potentially making them vulnerable to depression owing to their dual responsibilities. Investigating working mothers’ mental health status is important on both the individual and societal levels. This study aimed to explore the relationship between economic activity participation and depressive symptoms among working mothers.

Methods

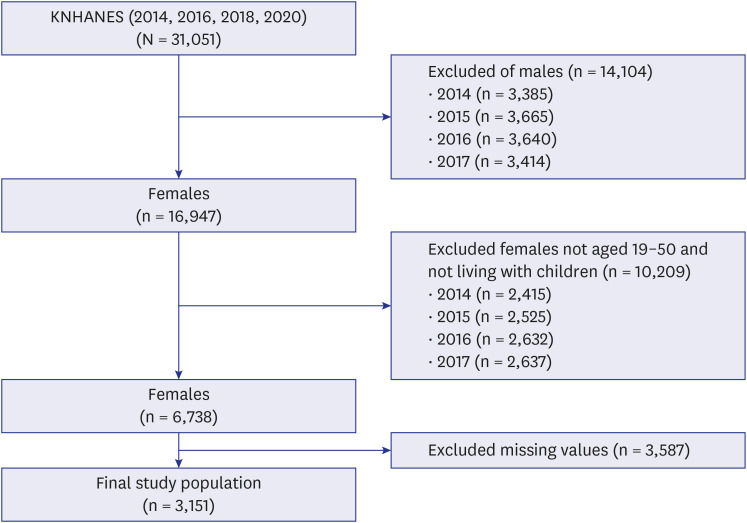

This study was a cross-sectional study and used data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey collected in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020. The participants in the study were women aged 19 to 50 who were residing with their children. In the total, 3,151 participants were used in the analysis. The independent variable was economic activity, categorized into two groups: 1) economically active and 2) economically inactive. The dependent variable was the depressive symptoms, categorized as present for a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score of ≥ 10 and absent for a score < 10. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association between economic activity and depressive symptoms, and sensitivity analyses were performed based on the severity of depressive symptoms.

Results

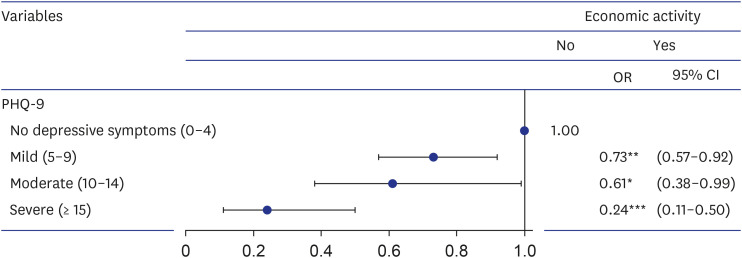

Among women with children, economically active women had reduced odds ratio of depressive symptoms compared with economically inactive women (odds ratio [OR], 0.54; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.36–0.80). In additional analysis, women working as wage earners had the lowest odds of depressive symptoms (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.28–0.66). Women working an average of 40 hours or less per week were least likely to have depressive symptoms (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.25–0.69).

Conclusion

Economic activity is significantly associated with depressive symptoms among women with children. Environmental support and policy approaches are needed to ensure that women remain economically active after childbirth.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Mehra R, Gammage S. Trends, countertrends, and gaps in women’s employment. World Dev. 1999; 27(3):533–550.2. OECD. Labour Force Statistics. Paris, France: OECD;2023.3. Busch F. Gender segregation, occupational sorting, and growth of wage disparities between women. Demography. 2020; 57(3):1063–1088. PMID: 32572788.4. Ramirez FO, Wotipka CM. Slowly but surely? The global expansion of women’s participation in science and engineering fields of study, 1972-92. Sociol Educ. 2001; 74(3):231–251.5. Baloch A, Shah SZ, Noor ZM, Rasheed B. An empirical analysis of the impact of gender gap on economic growth: a panel data approach. Empir Econ Lett. 2016; 15(12):1157–1166.6. Jensen PH, Møberg RJ. Does women’s employment enhance women’s citizenship? Eur Soc. 2017; 19(2):178–201.7. Statistics Korea. 2023 First Half Regional Employment Survey Korea. Daejeon, Korea: Statistics Korea;2023.8. Bianchi SM. Maternal employment and time with children: dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2000; 37(4):401–414. PMID: 11086567.9. Baxter J. Mothers’ employment transitions following childbirth. Fam Matters. 2005; 71:11–17.10. Lucia-Casademunt AM, García-Cabrera AM, Padilla-Angulo L, Cuéllar-Molina D. Returning to work after childbirth in Europe: well-being, work-life balance, and the interplay of supervisor support. Front Psychol. 2018; 9:68. PMID: 29467695.11. Abd Rahman NA, Susanto H. Effects of Employee Performance on the Implementation of Total Quality Management: Perspective of Working Mothers. Handbook of Research on Big Data, Green Growth, and Technology Disruption in Asian Companies and Societies. Pennsylvania, PA, USA: IGI Global;2022. p. 175–194.12. Chase-Lansdale PL, Moffitt RA, Lohman BJ, Cherlin AJ, Coley RL, Pittman LD, et al. Mothers’ transitions from welfare to work and the well-being of preschoolers and adolescents. Science. 2003; 299(5612):1548–1552. PMID: 12624259.13. Dugan AG, Barnes-Farrell JL. Working mothers’ second shift, personal resources, and self-care. Community Work Fam. 2020; 23(1):62–79.14. Smith EJ. The working mother: a critique of the research. J Vocat Behav. 1981; 19(2):191–211.15. Hill EJ. Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. J Fam Issues. 2005; 26(6):793–819.16. Boyar SL, Maertz CP Jr, Mosley DC Jr, Carr JC. The impact of work/family demand on work‐family conflict. J Manag Psychol. 2008; 23(3):215–235.17. Maji S. Society and ‘good woman’: a critical review of gender difference in depression. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018; 64(4):396–405. PMID: 29600733.18. Kim SK, Park S, Rhee H. The effect of work-family conflict on depression in married working women. Journal of Digital Convergence. 2017; 15(3):267–275.19. Erdwins CJ, Buffardi LC, Casper WJ, O’Brien AS. The relationship of women’s role strain to social support, role satisfaction, and self‐efficacy. Fam Relat. 2001; 50(3):230–238.20. Michel JS, Kotrba LM, Mitchelson JK, Clark MA, Baltes BB. Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta‐analytic review. J Organ Behav. 2011; 32(5):689–725.21. McCarten J. Differences in Depression, Anxiety, Self-Esteem, and Parenting Stress Between Employed and Stay-at-Home Mothers: A Meta-Analysis. Clemson, SC, USA: Clemson University;2003. p. 9–21.22. Momsen KM, Carlson JA. To know I can might be enough: Women’s self-efficacy and their identified leadership values. Advancing Women in Leadership Journal. 2013; 33:122–131.23. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43(1):69–77. PMID: 24585853.24. Kim W, Park EC, Lee TH, Kim TH. Effect of working hours and precarious employment on depressive symptoms in South Korean employees: a longitudinal study. Occup Environ Med. 2016; 73(12):816–822. PMID: 27540105.25. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID: 11556941.26. Shin C, Kim Y, Park S, Yoon S, Ko YH, Kim YK, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in general population of Korea: results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(11):1861–1869. PMID: 28960042.27. Angrist J, Evans WN. Children and Their Parents’ Labor Supply: Evidence From Exogenous Variation in Family Size. Cambridge, MA, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research;1996.28. Modini M, Joyce S, Mykletun A, Christensen H, Bryant RA, Mitchell PB, et al. The mental health benefits of employment: Results of a systematic meta-review. Australas Psychiatry. 2016; 24(4):331–336. PMID: 26773063.29. Junna L, Moustgaard H, Martikainen P. Current unemployment, unemployment history, and mental health: a fixed-effects model approach. Am J Epidemiol. 2022; 191(8):1459–1469. PMID: 35441659.30. Virgolino A, Costa J, Santos O, Pereira ME, Antunes R, Ambrósio S, et al. Lost in transition: a systematic review of the association between unemployment and mental health. J Ment Health. 2022; 31(3):432–444. PMID: 34983292.31. Peterson ER, Andrejic N, Corkin MT, Waldie KE, Reese E, Morton SM. I hardly see my baby: challenges and highlights of being a New Zealand working mother of an infant. Kotuitui. 2018; 13(1):4–28.32. Crockett MW. Depression in middle-aged women. J Pastoral Care. 1977; 31(1):47–55.33. Talala K, Huurre T, Aro H, Martelin T, Prättälä R. Socio-demographic differences in self-reported psychological distress among 25-to 64-year-old Finns. Soc Indic Res. 2008; 86(2):323–335.34. Qian G, Mei J, Tian L, Dou G. Assessing mothers’ parenting stress: differences between one-and two-child families in China. Front Psychol. 2021; 11:609715. PMID: 33519622.35. Vives A, Amable M, Ferrer M, Moncada S, Llorens C, Muntaner C, et al. Employment precariousness and poor mental health: evidence from Spain on a new social determinant of health. J Environ Public Health. 2013; 2013:978656. PMID: 23431322.36. Han KM, Chang J, Won E, Lee MS, Ham BJ. Precarious employment associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in adult wage workers. J Affect Disord. 2017; 218:201–209. PMID: 28477498.37. Dinh H, Strazdins L, Welsh J. Hour-glass ceilings: work-hour thresholds, gendered health inequities. Soc Sci Med. 2017; 176:42–51. PMID: 28129546.38. Young FY. Work-life balance and mental health conditions during a reduction in the number of working hours: a follow-up study of Hong Kong retail industry workers. Int J Bus Inf. 2018; 13:489–504.39. Sato K, Kuroda S, Owan H. Mental health effects of long work hours, night and weekend work, and short rest periods. Soc Sci Med. 2020; 246:112774. PMID: 31923837.40. Yoo J. An Empirical Study on the Labor Force Participation Behavior of Married Women: Focusing on Personal, Household, and Policy-Related Factors. Seoul, Korea: Korea Association for Policy Analysis and Evaluation;2015. p. 23–48.41. Lee J, Son S. Mothers’ Work-Family Conflict in Dual-Earner Families with Young Children: The Role of Resources and Perceptions Related to Work and Child Care. Seoul, Korea: Korean Association of Family Relations;2013. p. 93–114.42. Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS. When work–family benefits are not enough: the influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work–family conflict. J Vocat Behav. 1999; 54(3):392–415.43. Yun J, Kim CY, Son SH, Bae CW, Choi YS, Chung SH. Birth rate transition in the Republic of Korea: trends and prospects. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(42):e304. PMID: 36325608.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Relationship between Depressive Tendency in Postpartum Women and Factors such as Infant Temperament, Parentiong Stress and Coping Style

- The Effect of the Mother-Child Development Promotion Program for the Child with Developmental Delay on Mother's Depressive Mood and Parenting Stress

- Parents' Rearing Attitude of Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Depressive Disorder

- Correlates of Depression among Married Immigrant Women in Korea

- Comparison of Children's Body Weights and Eating Habits by Maternal Parenting Attitudes Perceived by Children