Clin Transplant Res.

2024 Jun;38(2):150-153. 10.4285/ctr.24.0011.

Sternoclavicular xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis in a patient after kidney transplantation: a case report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Suwan Happiness Geriatric Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- 2Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Chosun University Hospital, Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea

- 3Department of Pathology, Chosun University Hospital, Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2557609

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/ctr.24.0011

Abstract

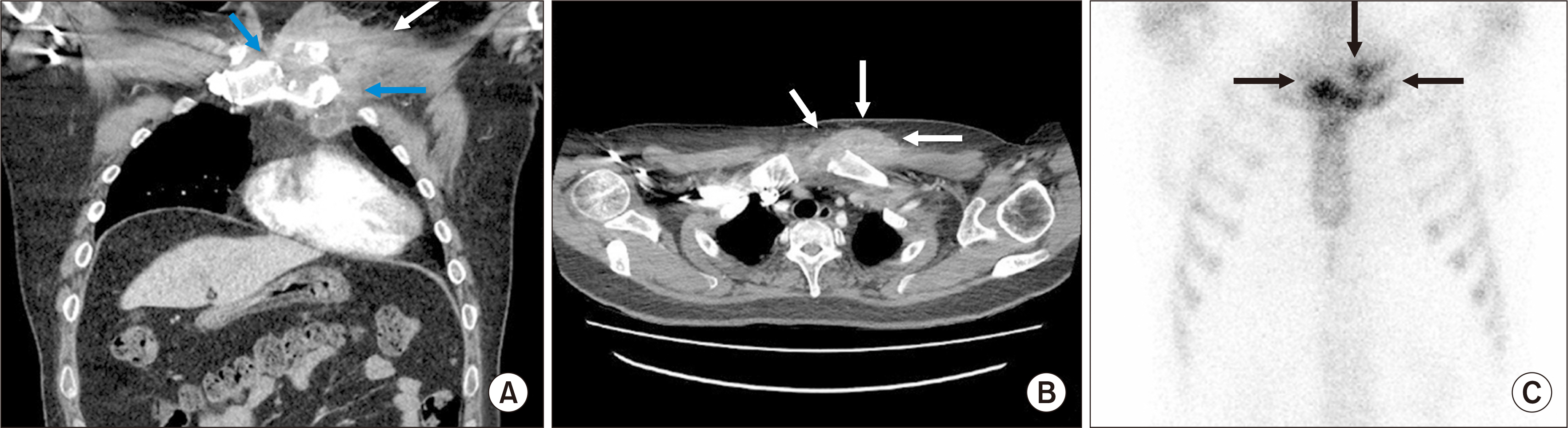

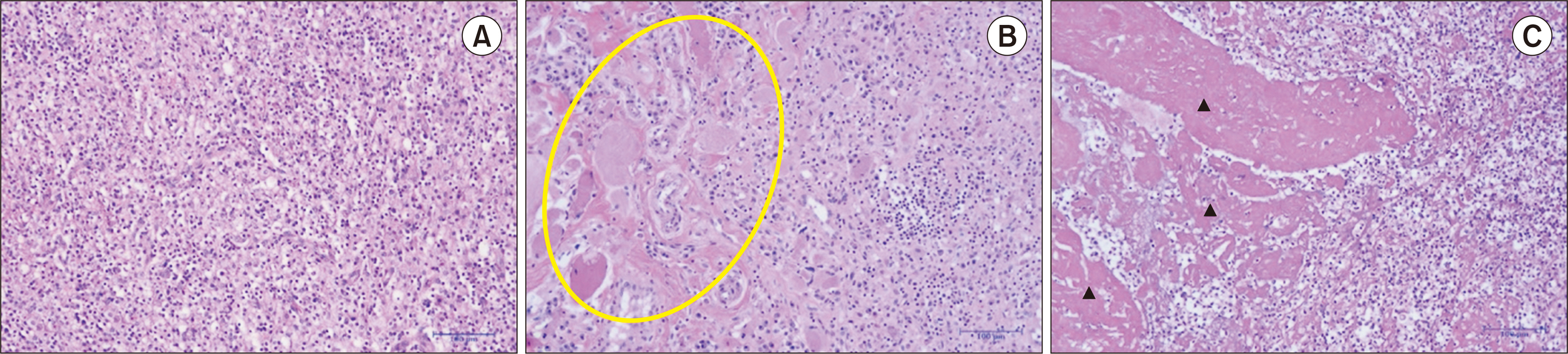

- Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis (XO) is a rare chronic inflammatory bone disease characterized by the presence of cholesterol-laden foam macrophages, histiocytes, and plasma cells. We report the case of a 41-year-old man with end-stage renal disease who had undergone deceased donor kidney transplantation 4 years earlier. He presented with a chest wall mass that he had first identified 2 weeks prior to admission. Computed tomography revealed a periosseous heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass adjacent to the sternal end of the left clavicle, accompanied by irregular and destructive osteolytic lesions on the left side of the sternal manubrium. A total mass resection, which included partial clavicle and sternum removal, was performed. Pathological examination revealed foamy histiocytes along with numerous lymphoplasmacytic cells, confirming the diagnosis of XO. This case underscores the potential for XO to develop following kidney transplantation.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cozzutto C, Carbone A. 1988; The xanthogranulomatous process. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation. Pathol Res Pract. 183:395–402. DOI: 10.1016/S0344-0338(88)80085-2. PMID: 3054826.2. Guzmán-Valdivia G. 2004; Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: 15 years' experience. World J Surg. 28:254–7. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-003-7161-y. PMID: 14961199.

Article3. Singh SK, Khandelwal AK, Pawar DS, Sen R, Sharma S. 2010; Xanthogranulomatous cystitis: a rare clinical entity. Urol Ann. 2:125–6. DOI: 10.4103/0974-7796.68863. PMID: 20981202. PMCID: PMC2955229.

Article4. Solooki S, Hoveidaei AH, Kardeh B, Azarpira N, Salehi E. 2019; Xanthogranulomatous Osteomyelitis of the tibia. Ochsner J. 19:276–81. DOI: 10.31486/toj.18.0165. PMID: 31528142. PMCID: PMC6735604.

Article5. Nakashiro H, Haraoka S, Fujiwara K, Harada S, Hisatsugu T, Watanabe T. 1995; Xanthogranulomatous cholecystis. Cell composition and a possible pathogenetic role of cell-mediated immunity. Pathol Res Pract. 191:1078–86. DOI: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80651-5. PMID: 8822108.6. Girschick HJ, Huppertz HI, Harmsen D, Krauspe R, Müller-Hermelink HK, Papadopoulos T. 1999; Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: diagnostic value of histopathology and microbial testing. Hum Pathol. 30:59–65. DOI: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90301-5. PMID: 9923928.

Article7. Unni KK, McLeod RA, Dahlin DC. 1980; Conditions that simulate primary neoplasms of bone. Pathol Annu. 15(Pt 1):91–131. DOI: 10.55418/188104193x-14. PMID: 6969388.8. Cozzutto C. 1984; Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 108:973–6. DOI: 10.4103/2321-4848.144352. PMID: 6334505.9. Wittig JC, Bickels J, Priebat D, Jelinek J, Kellar-Graney K, Shmookler B, et al. 2002; Osteosarcoma: a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 65:1123–32. PMID: 11925089.10. Borjian A, Rezaei F, Eshaghi MA, Shemshaki H. 2012; Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. J Orthop Traumatol. 13:217–20. DOI: 10.1007/s10195-011-0165-8. PMID: 22075672. PMCID: PMC3506838.

Article11. Perera A, Rus M, Thom M, Critchley G. 2022; Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis of the cervical spine. Br J Neurosurg. 1–5. DOI: 10.1080/02688697.2022.2086967. PMID: 35695311.

Article12. Vankalakunti M, Saikia UN, Mathew M, Kang M. 2007; Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis of ulna mimicking neoplasm. World J Surg Oncol. 5:46. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-46. PMID: 17470270. PMCID: PMC1865539.

Article13. Scicluna C, Babic D, Ellul P. 2020; Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis and Crohn's disease: a possible association? GE Port J Gastroenterol. 27:62–4. DOI: 10.1159/000500208. PMID: 31970246. PMCID: PMC6959117.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Xanthogranulomatous Osteomyelitis Presenting as a Subacute Infectious Condition in the Fibula of a Young Female

- Salmonella Osteomyelitis of the Sternoclavicular Joint Mimicking Tuberculosis in an Otherwise Healthy Person

- A Case of Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis Associated with Xanthogranulomatous Epididymoorchitis

- A Case of Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis which was Confused with Renal Pelvic Tumor

- Focal Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis: Reports of 2 Cases