J Korean Foot Ankle Soc.

2024 Jun;28(2):41-47. 10.14193/jkfas.2024.28.2.41.

Application of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in the Foot and Ankle Field

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, College of Medicine and Gyeongsang National University and Changwon Hospital, Changwon, Korea

- 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, College of Medicine and Gyeongsang National University and Hospital, Jinju, Korea

- 3Institute of Medical Science, Gyeongsang National University College of Medicine, Jinju, Korea

- KMID: 2556552

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14193/jkfas.2024.28.2.41

Abstract

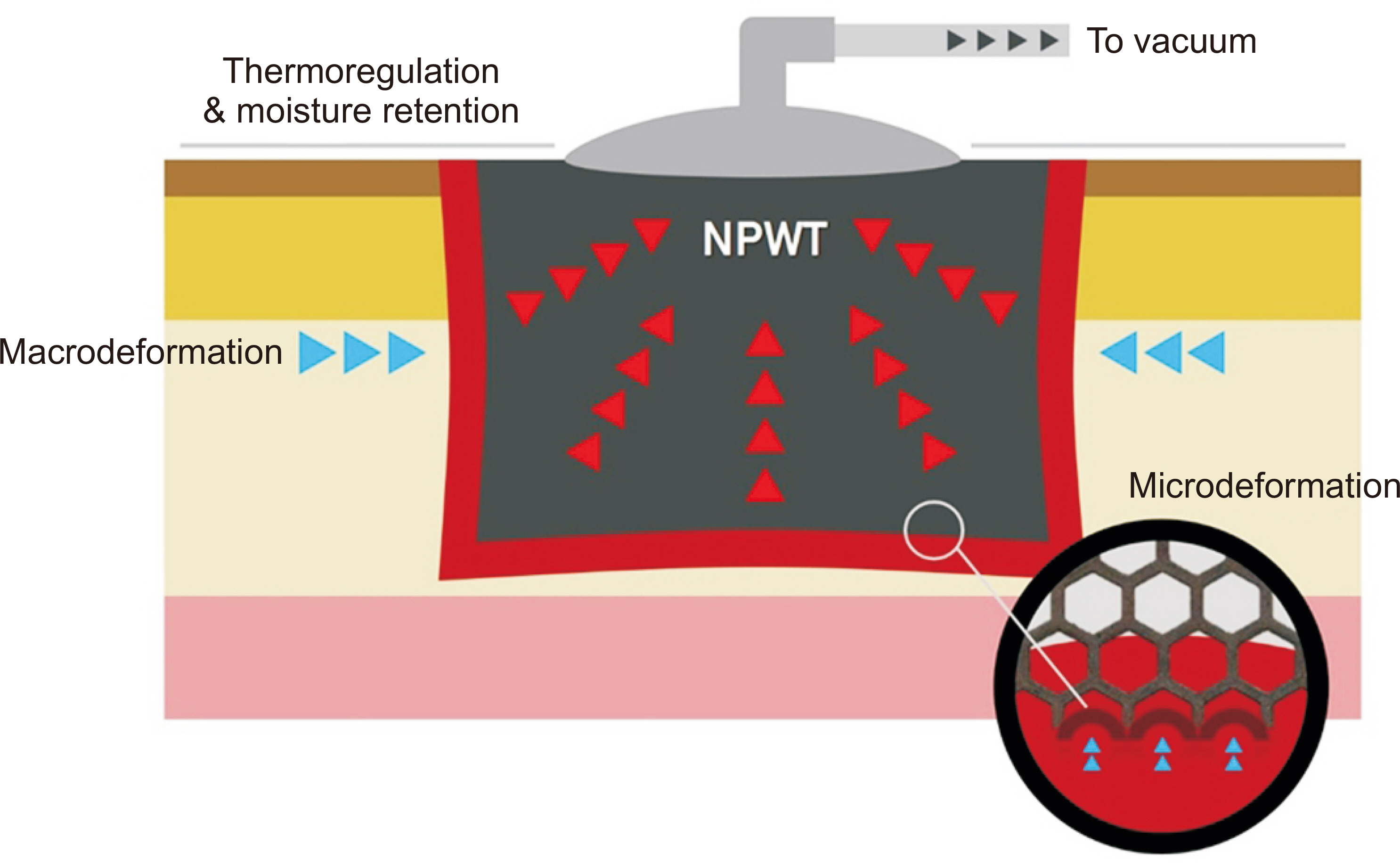

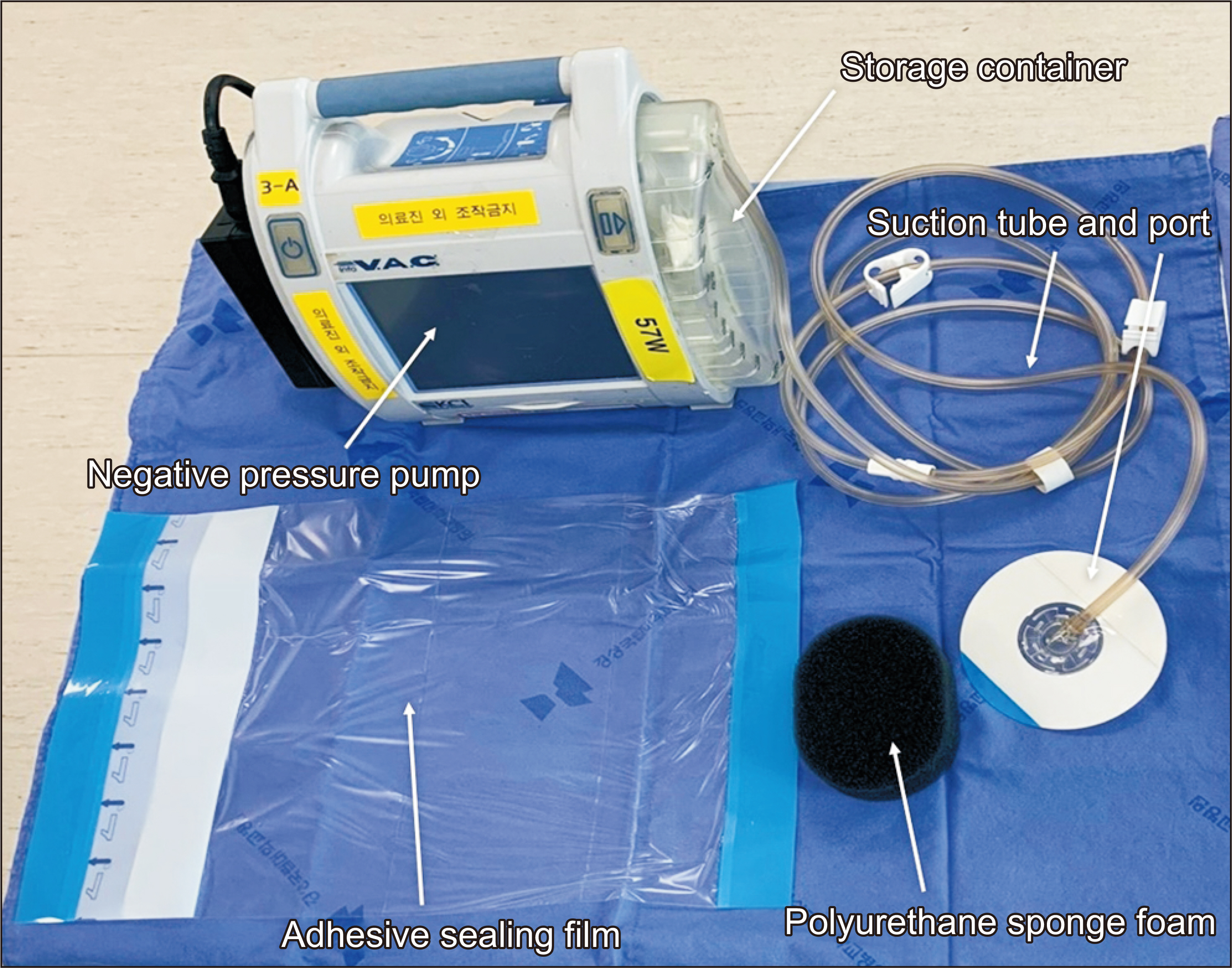

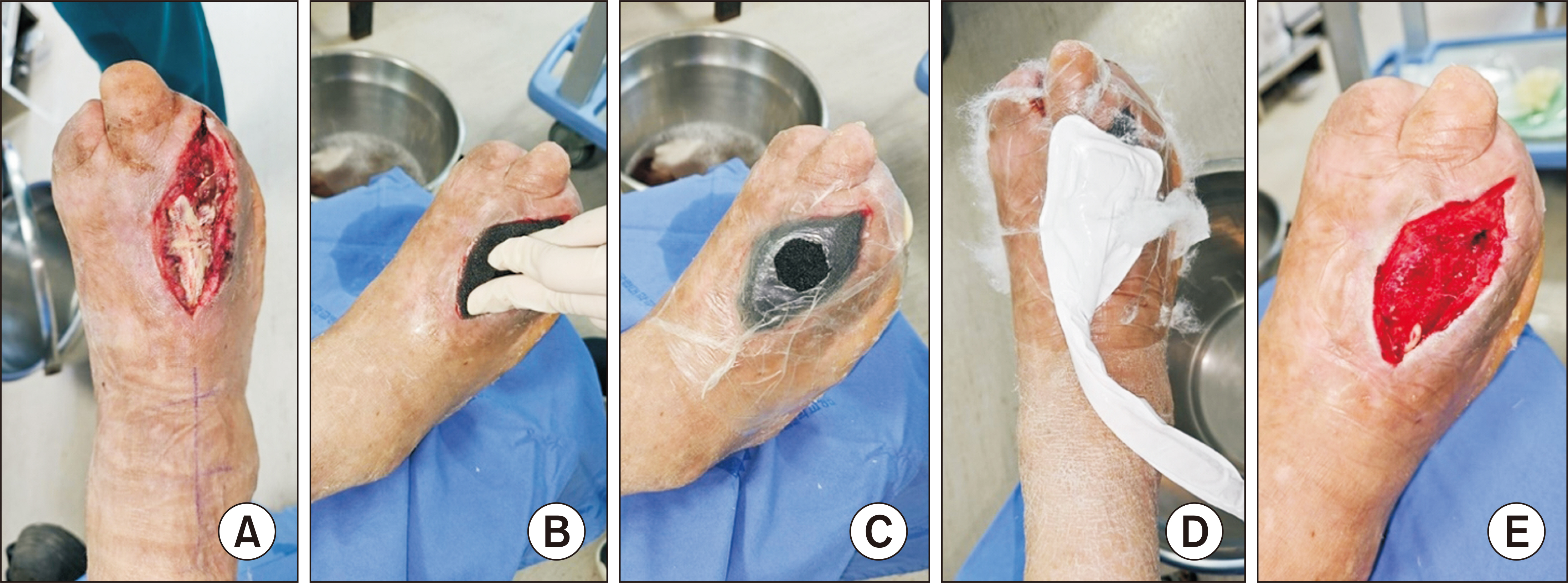

- Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has emerged as a valuable tool for managing complex wounds within the foot and ankle field. This review article discusses the expanding applications of NPWT in this specialized field. Specifically, it discusses the efficacy of NPWT for various wound types, including diabetic foot wounds, traumatic wounds, surgical wounds, and wounds involving exposed bone or soft tissue defects. NPWT demonstrates versatile utility for foot and ankle wound management by promoting healing, potentially reducing the need for secondary surgery, improving diabetic and neuropathic ulcer healing times and outcomes, and optimizing the healing of high-risk incisions. In addition, this review explores the underlying mechanisms through which NPWT might enhance wound healing. By synthesizing current evidence, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the role of NPWT in foot and ankle surgery and offers valuable insights to clinicians navigating the complexities of wound care in this challenging anatomical area.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ, Marks MW, DeFranzo AJ, Molnar JA, David LR. 2006; Vacuum-assisted closure: state of clinic art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 117(7 Suppl):127S–42S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222551.10793.51. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222551.10793.51. PMID: 16799380.

Article2. Orgill DP, Bayer LR. 2011; Update on negative-pressure wound therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 127 Suppl 1:105S–15S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318200a427. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318200a427. PMID: 21200280.

Article3. Shiffman MA. Shiffman MA, editor. 2020. History of Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy(NPWT). Pressure Injury, Diabetes and Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. Springer;p. 223–8. DOI: 10.1007/15695_2017_50.4. Okhotsky V, Kaulen D, Klopov L. 1973; The vacuum method in the primary surgical debridement of the open limb traumas. Sov Med. 1:17–20.5. Chariker ME. 1989; Effective management of incisional and cutaneous fistulae with closed suction wound drainage. Contemp Surg. 34:59–63.6. Kostiuchenok BM, Kolker II, Karlov VA, Ignatenko SN, Muzykant LI. 1986; [Vacuum treatment in the surgical management of suppurative wounds]. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek. 137:18–21. Russian.7. Fleischmann W, Becker U, Bischoff M, Hoekstra H. 1995; Vacuum sealing: indication, technique, and results. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 5:37–40. doi: 10.1007/BF02716212. DOI: 10.1007/BF02716212. PMID: 24193271.

Article8. Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. 1997; Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 38:563–76. discussion 577. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00002. DOI: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00002. PMID: 9188971.9. Bucalo B, Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. 1993; Inhibition of cell proliferation by chronic wound fluid. Wound Repair Regen. 1:181–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1993.10308.x. DOI: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1993.10308.x. PMID: 17163887.

Article10. Orgill DP, Manders EK, Sumpio BE, Lee RC, Attinger CE, Gurtner GC, et al. 2009; The mechanisms of action of vacuum assisted closure: more to learn. Surgery. 146:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.002. PMID: 19541009.

Article11. Kairinos N, Solomons M, Hudson DA. 2009; Negative-pressure wound therapy I: the paradox of negative-pressure wound therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 123:589–98. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181956551. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181956551. PMID: 19182617.

Article12. Huang C, Leavitt T, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. 2014; Effect of negative pressure wound therapy on wound healing. Curr Probl Surg. 51:301–31. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.04.001. DOI: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.04.001. PMID: 24935079.

Article13. Anghel EL, Kim PJ. 2016; Negative-pressure wound therapy: a comprehensive review of the evidence. Plast Reconstr Surg. 138(3 Suppl):129S–37S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002645. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002645. PMID: 27556753.

Article14. Breen E, Tang K, Olfert M, Knapp A, Wagner P. 2008; Skeletal muscle capillarity during hypoxia: VEGF and its activation. High Alt Med Biol. 9:158–66. doi: 10.1089/ham.2008.1010. DOI: 10.1089/ham.2008.1010. PMID: 18578647.

Article15. Kairinos N, Voogd AM, Botha PH, Kotze T, Kahn D, Hudson DA, et al. 2009; Negative-pressure wound therapy II: negative-pressure wound therapy and increased perfusion. Just an illusion? Plast Reconstr Surg. 123:601–12. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318196b97b. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318196b97b. PMID: 19182619.

Article16. Wackenfors A, Sjögren J, Gustafsson R, Algotsson L, Ingemansson R, Malmsjö M. 2004; Effects of vacuum-assisted closure therapy on inguinal wound edge microvascular blood flow. Wound Repair Regen. 12:600–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12602.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12602.x. PMID: 15555050.

Article17. Greene AK, Puder M, Roy R, Arsenault D, Kwei S, Moses MA, et al. 2006; Microdeformational wound therapy: effects on angiogenesis and matrix metalloproteinases in chronic wounds of 3 debilitated patients. Ann Plast Surg. 56:418–22. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000202831.43294.02. DOI: 10.1097/01.sap.0000202831.43294.02. PMID: 16557076.18. Hafeez K, Kaim Khani GM, Kumar D, Kumar S. Haroon-Ur-Rashid. 2015; Vacuum Assisted Closure- utilization as home based therapy in the management of complex diabetic extremity wounds. Pak J Med Sci. 31:95–9. doi: 10.12669/pjms.311.6093. DOI: 10.12669/pjms.311.6093. PMID: 25878622. PMCID: PMC4386165.19. Yao M, Fabbi M, Hayashi H, Park N, Attala K, Gu G, et al. 2014; A retrospective cohort study evaluating efficacy in high-risk patients with chronic lower extremity ulcers treated with negative pressure wound therapy. Int Wound J. 11:483–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01113.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01113.x. PMID: 23163962. PMCID: PMC7950652.

Article20. Dzieciuchowicz Ł, Kruszyna Ł, Espinosa G. Krasiński Z. 2012; Monitoring of systemic inflammatory response in diabetic patients with deep foot infection treated with negative pressure wound therapy. Foot Ankle Int. 33:832–7. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0832. DOI: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0832. PMID: 23050705.

Article21. McCallon SK, Knight CA, Valiulus JP, Cunningham MW, McCulloch JM, Farinas LP. 2000; Vacuum-assisted closure versus saline-moistened gauze in the healing of postoperative diabetic foot wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 46:28–32. 3422. Birke-Sorensen H, Malmsjo M, Rome P, Hudson D, Krug E, Berg L, et al. 2011; Evidence-based recommendations for negative pressure wound therapy: treatment variables (pressure levels, wound filler and contact layer)--steps towards an international consensus. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 64(Suppl):S1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.06.001. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.06.001. PMID: 21868296.23. Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. 1997; Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 38:553–62. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00001. DOI: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00001. PMID: 9188970.24. Lavery LA, Murdoch DP, Kim PJ, Fontaine JL, Thakral G, Davis KE. 2014; Negative pressure wound therapy with low pressure and gauze dressings to treat diabetic foot wounds. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 8:346–9. doi: 10.1177/1932296813519012. DOI: 10.1177/1932296813519012. PMID: 24876586. PMCID: PMC4455400.

Article25. Lee KN, Ben-Nakhi M, Park EJ, Hong JP. 2015; Cyclic negative pressure wound therapy: an alternative mode to intermittent system. Int Wound J. 12:686–92. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12201. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.12201. PMID: 24373578. PMCID: PMC7950479.

Article26. Borys S, Hohendorff J, Koblik T, Witek P, Ludwig-Slomczynska AH, Frankfurter C, et al. 2018; Negative-pressure wound therapy for management of chronic neuropathic noninfected diabetic foot ulcerations - short-term efficacy and long-term outcomes. Endocrine. 62:611–6. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1707-0. DOI: 10.1007/s12020-018-1707-0. PMID: 30099674. PMCID: PMC6244911.

Article27. Yang C, Goss SG, Alcantara S, Schultz G, Lantis Ii JC. 2017; Effect of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation on bioburden in chronically infected wounds. Wounds. 29:240–6.28. Saini R, Jeyaraman M, Jayakumar T, Iyengar KP, Jeyaraman N, Jain VK. 2023; Evolving role of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d-) in management of trauma and orthopaedic wounds: mechanism, applications and future perspectives. Indian J Orthop. 57:1968–83. doi: 10.1007/s43465-023-01018-x. DOI: 10.1007/s43465-023-01018-x. PMID: 38009182.

Article29. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, Evans KK, Lehner B, Willy C, et al. 2013; Negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation: international consensus guidelines. Plast Reconstr Surg. 132:1569–79. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a80586. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a80586. PMID: 24005370.30. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Steinberg JS, Evans KK, Powers KA, Hung RW, et al. 2014; The impact of negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation compared with standard negative-pressure wound therapy: a retrospective, historical, cohort, controlled study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 133:709–16. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438060.46290.7a. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438060.46290.7a. PMID: 24572860.31. White RA, Miki RA, Kazmier P, Anglen JO. 2005; Vacuum-assisted closure complicated by erosion and hemorrhage of the anterior tibial artery. J Orthop Trauma. 19:56–9. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200501000-00011. DOI: 10.1097/00005131-200501000-00011. PMID: 15668586.

Article32. Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Mesbahi AN, Hess CL, Graw KS. 2005; Mechanisms and clinical applications of the vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 6:185–94. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506030-00005. DOI: 10.2165/00128071-200506030-00005. PMID: 15943495.33. Kim PJ, Attinger CE, Oliver N, Garwood C, Evans KK, Steinberg JS, et al. 2015; Comparison of outcomes for normal saline and an antiseptic solution for negative-pressure wound therapy with instillation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 136:657e–64e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001709. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001709. PMID: 26505723.

Article34. Glass GE, Murphy GRF, Nanchahal J. 2017; Does negative-pressure wound therapy influence subjacent bacterial growth? A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 70:1028–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.027. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.027. PMID: 28602266.

Article35. Dumville JC, Hinchliffe RJ, Cullum N, Game F, Stubbs N, Sweeting M, et al. 2013; Negative pressure wound therapy for treating foot wounds in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (10):CD010318. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010318.pub2. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010318.pub2.

Article36. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Diabetic Foot Study Consortium. 2005; Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 366:1704–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67695-7. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67695-7. PMID: 16291063.

Article37. Blume PA, Walters J, Payne W, Ayala J, Lantis J. 2008; Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum-assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 31:631–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2196. DOI: 10.2337/dc07-2196. PMID: 18162494.

Article38. Mouës CM, van den Bemd GJ, Heule F, Hovius SE. 2007; Comparing conventional gauze therapy to vacuum-assisted closure wound therapy: a prospective randomised trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 60:672–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.01.041. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.01.041. PMID: 17485058.

Article39. Jiang ZY, Yu XT, Liao XC, Liu MZ, Fu ZH, Min DH, et al. 2021; Negative-pressure wound therapy in skin grafts: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Burns. 47:747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2021.02.012. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2021.02.012. PMID: 33814213.

Article40. Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Newton K, Dumville JC, Costa ML, Norman G, Bruce J. 2018; Negative pressure wound therapy for open traumatic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7:CD012522. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012522.pub2. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012522.pub2. PMID: 29969521.

Article41. Burtt KE, Badash I, Leland HA, Gould DJ, Rounds AD, Patel KM, et al. 2020; The efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy and antibiotic beads in lower extremity salvage. J Surg Res. 247:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.09.055. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.09.055. PMID: 31690532.

Article42. Zenke Y, Inokuchi K, Okada H, Ooae K, Matsui K, Sakai A. 2014; Useful technique using negative pressure wound therapy on postoperative lower leg open wounds with compartment syndrome. Inj Extra. 45:83–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.07.015. DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.07.015.

Article43. Onoe A, Muroya T, Nakamura Y, Nakamura F, Yagura T, Nakajima M, et al. 2023; Efficacy of the shoelace technique for extremity fasciotomy wounds due to compartment syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 24:704. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06849-1. DOI: 10.1186/s12891-023-06849-1. PMID: 37667241. PMCID: PMC10476399.

Article44. Petzina R, Malmsjö M, Stamm C, Hetzer R. 2010; Major complications during negative pressure wound therapy in poststernotomy mediastinitis after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 140:1133–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.063. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.06.063. PMID: 20832086.

Article45. Normandin S, Safran T, Winocour S, Chu CK, Vorstenbosch J, Murphy AM, et al. 2021; Negative pressure wound therapy: mechanism of action and clinical applications. Semin Plast Surg. 35:164–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731792. DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-1731792. PMID: 34526864. PMCID: PMC8432996.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy for Septic Ankle Arthritis Following Intractable Lateral Malleolar Bursitis: A Case Report

- Orthotic and Prosthetic Options after Diabetic Foot Amputation

- The Effectiveness of Vacuum-Assisted Closure (V.A.C) Dressing combined with Silver Dressing Material in Open Fracture of the Foot and Ankle

- Unhealed Wound of the Lower Leg due to Synovial Fistula of the Ankle Joint

- Prognostic Factors of Wound Healing after Diabetic Foot Amputation; ABI, TBI, and Toe Pressure