Korean Circ J.

2024 Jun;54(6):295-310. 10.4070/kcj.2024.0065.

COVID-19 Vaccination-Related Myocarditis: What We Learned From Our Experience and What We Need to Do in The Future

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Cardiology in Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea

- 2Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School and Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2556527

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2024.0065

Abstract

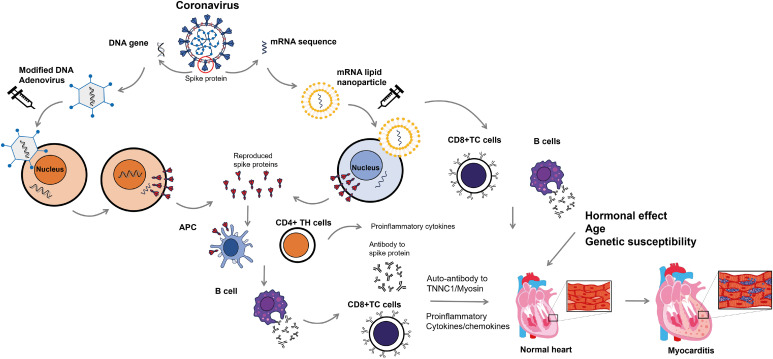

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has led to a global health crisis with substantial mortality and morbidity. To combat the COVID-19 pandemic, various vaccines have been developed, but unexpected serious adverse events including vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia, carditis, and thromboembolic events have been reported and became a huddle for COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccine-related myocarditis (VRM) is a rare but significant adverse event associated primarily with mRNA vaccines. This review explores the incidence, risk factors, clinical presentation, pathogenesis, management strategies, and outcomes associated with VRM. The incidence of VRM is notably higher in male adolescents and young adults, especially after the second dose of mRNA vaccines. The pathogenesis appears to involve an immune-mediated process, but the precise mechanism remains mostly unknown so far. Most studies have suggested that VRM is mild and self-limiting, and responds well to conventional treatment. However, a recent nationwide study in Korea warns that severe cases, including fulminant myocarditis or death, are not uncommon in patients with COVID-19 VRM. The long-term cardiovascular consequences of VRM have not been well understood and warrant further investigation. This review also briefly addresses the critical balance between the substantial benefits of COVID-19 vaccination and the rare risks of VRM in the coming endemic era. It emphasizes the need for continued surveillance, research to understand the underlying mechanisms, and strategies to mitigate risk. Filling these knowledge gaps would be vital to refining vaccination recommendations and improving patient care in the evolving COVID-19 pandemic landscape.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:2451–2460. PMID: 32412710.2. Jung J. Preparations for the assessment of COVID-19 infection and long-term cardiovascular risk. Korean Circ J. 2022; 52:808–813. PMID: 36347517.3. Barouch DH. COVID-19 vaccines - immunity, variants, boosters. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:1011–1020. PMID: 36044620.4. Liu R, Pan J, Zhang C, Sun X. Cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 vaccines. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022; 9:840929. PMID: 35369340.5. Walsh EE, Frenck RW Jr, Falsey AR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based COVID-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:2439–2450. PMID: 33053279.6. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384:403–416. PMID: 33378609.7. Falsey AR, Sobieszczyk ME, Hirsch I, et al. Phase 3 safety and efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385:2348–2360. PMID: 34587382.8. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384:2187–2201. PMID: 33882225.9. Pollack A, Kontorovich AR, Fuster V, Dec GW. Viral myocarditis--diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015; 12:670–680. PMID: 26194549.10. Ammirati E, Frigerio M, Adler ED, et al. Management of acute myocarditis and chronic inflammatory cardiomyopathy: an expert consensus document. Circ Heart Fail. 2020; 13:e007405. PMID: 33176455.11. Boehmer TK, Kompaniyets L, Lavery AM, et al. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data - United States, March 2020-January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021; 70:1228–1232. PMID: 34473684.12. Rafaniello C, Gaio M, Zinzi A, et al. Disentangling a thorny issue: myocarditis and pericarditis post COVID-19 and following mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022; 15:525. PMID: 35631352.13. Verma AK, Lavine KJ, Lin CY. Myocarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385:1332–1334. PMID: 34407340.14. Heidecker B, Dagan N, Balicer R, et al. Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccine: incidence, presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, therapy, and outcomes put into perspective. A clinical consensus document supported by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022; 24:2000–2018. PMID: 36065751.15. Heymans S, Cooper LT. Myocarditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination: clinical observations and potential mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022; 19:75–77. PMID: 34887571.16. Rout A, Suri S, Vorla M, Kalra DK. Myocarditis associated with COVID-19 and its vaccines - a systematic review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022; 74:111–121. PMID: 36279947.17. Eckart RE, Love SS, Atwood JE, et al. Incidence and follow-up of inflammatory cardiac complications after smallpox vaccination. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004; 44:201–205. PMID: 15234435.18. Straus W, Urdaneta V, Esposito DB, et al. Analysis of Myocarditis among 252 million mRNA-1273 recipients worldwide. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 76:e544–e552. PMID: 35666513.19. Oster ME, Shay DK, Su JR, et al. Myocarditis cases reported after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination in the US from December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA. 2022; 327:331–340. PMID: 35076665.20. Goddard K, Lewis N, Fireman B, et al. Risk of myocarditis and pericarditis following BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccine. 2022; 40:5153–5159. PMID: 35902278.21. Simone A, Herald J, Chen A, et al. Acute myocarditis following COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in adults aged 18 years or older. JAMA Intern Med. 2021; 181:1668–1670. PMID: 34605853.22. Diaz GA, Parsons GT, Gering SK, Meier AR, Hutchinson IV, Robicsek A. Myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021; 326:1210–1212. PMID: 34347001.23. Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, et al. Myocarditis following immunization with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in members of the US military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021; 6:1202–1206. PMID: 34185045.24. Canada government. Reported side effects following COVID-19 vaccination in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: Canada government;2023. cited 2024 January 1. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccine-safety/#detailedSafetySignals.25. Karlstad Ø, Hovi P, Husby A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and myocarditis in a Nordic cohort study of 23 million residents. JAMA Cardiol. 2022; 7:600–612. PMID: 35442390.26. Patone M, Mei XW, Handunnetthi L, et al. Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022; 28:410–422. PMID: 34907393.27. Le Vu S, Bertrand M, Jabagi MJ, et al. Age and sex-specific risks of myocarditis and pericarditis following COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines. Nat Commun. 2022; 13:3633. PMID: 35752614.28. Husby A, Hansen JV, Fosbøl E, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and myocarditis or myopericarditis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2021; 375:e068665. PMID: 34916207.29. Massari M, Spila Alegiani S, Morciano C, et al. Postmarketing active surveillance of myocarditis and pericarditis following vaccination with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in persons aged 12 to 39 years in Italy: a multi-database, self-controlled case series study. PLoS Med. 2022; 19:e1004056. PMID: 35900992.30. Cho JY, Kim KH, Lee N, et al. COVID-19 vaccination-related myocarditis: a Korean nationwide study. Eur Heart J. 2023; 44:2234–2243. PMID: 37264895.31. Mevorach D, Anis E, Cedar N, et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385:2140–2149. PMID: 34614328.32. Witberg G, Barda N, Hoss S, et al. Myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination in a large health care organization. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385:2132–2139. PMID: 34614329.33. Wong CK, Lau KT, Xiong X, et al. Adverse events of special interest and mortality following vaccination with mRNA (BNT162b2) and inactivated (CoronaVac) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in Hong Kong: a retrospective study. PLoS Med. 2022; 19:e1004018. PMID: 35727759.34. Heymans S, Eriksson U, Lehtonen J, Cooper LT Jr. The quest for new approaches in myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 68:2348–2364. PMID: 27884253.35. Sexson Tejtel SK, Munoz FM, Al-Ammouri I, et al. Myocarditis and pericarditis: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2022; 40:1499–1511. PMID: 35105494.36. Gilotra NA, Minkove N, Bennett MK, et al. Lack of relationship between serum cardiac troponin I level and giant cell myocarditis diagnosis and outcomes. J Card Fail. 2016; 22:583–585. PMID: 26768222.37. Younis A, Matetzky S, Mulla W, et al. Epidemiology characteristics and outcome of patients with clinically diagnosed acute myocarditis. Am J Med. 2020; 133:492–499. PMID: 31712098.38. Ammirati E, Veronese G, Brambatti M, et al. Fulminant versus acute nonfulminant myocarditis in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 74:299–311. PMID: 31319912.39. Schauer J, Caris E, Soriano B, et al. The diagnostic role of echocardiographic strain analysis in patients presenting with chest pain and elevated troponin: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022; 35:857–867. PMID: 35301094.40. Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:2636–2648. 2648a–2648d. PMID: 23824828.41. Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: a JACC White Paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:1475–1487. PMID: 19389557.42. Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:3158–3176. PMID: 30545455.43. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2023 Focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023; 44:3627–3639. PMID: 37622666.44. Park SM, Lee SY, Jung MH, et al. Korean Society of Heart Failure guidelines for the management of heart failure: management of the underlying etiologies and comorbidities of heart failure. Korean Circ J. 2023; 53:425–451. PMID: 37525389.45. Kociol RD, Cooper LT, Fang JC, et al. Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020; 141:e69–e92. PMID: 31902242.46. Kim KH. The role of COVID-19 vaccination for patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the upcoming endemic era. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2024; 13:21–28. PMID: 38299160.47. Wang WJ, Wang CY, Wang SI, Wei JC. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in COVID-19 survivors among non-vaccinated population: a retrospective cohort study from the TriNetX US collaborative networks. EClinicalMedicine. 2022; 53:101619. PMID: 35971425.48. Notarte KI, Catahay JA, Velasco JV, et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2022; 53:101624. PMID: 36051247.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Myocarditis Presenting With a Hyperechoic Nodule After the First Dose of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine

- Cardiac Imaging of Acute Myocarditis Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination

- COVID-19 vaccination–related cardiovascular complications

- Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings and Clinical Features of COVID-19 Vaccine-Associated Myocarditis, Compared With Those of Other Types of Myocarditis

- COVID-19 Vaccination in Korea