Korean J Orthod.

2024 May;54(3):185-195. 10.4041/kjod24.004.

Orthodontic diagnosis rates based on panoramic radiographs in children aged 6–8 years: A retrospective study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthodontics, Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Orthodontics, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

- KMID: 2556112

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4041/kjod24.004

Abstract

Objective

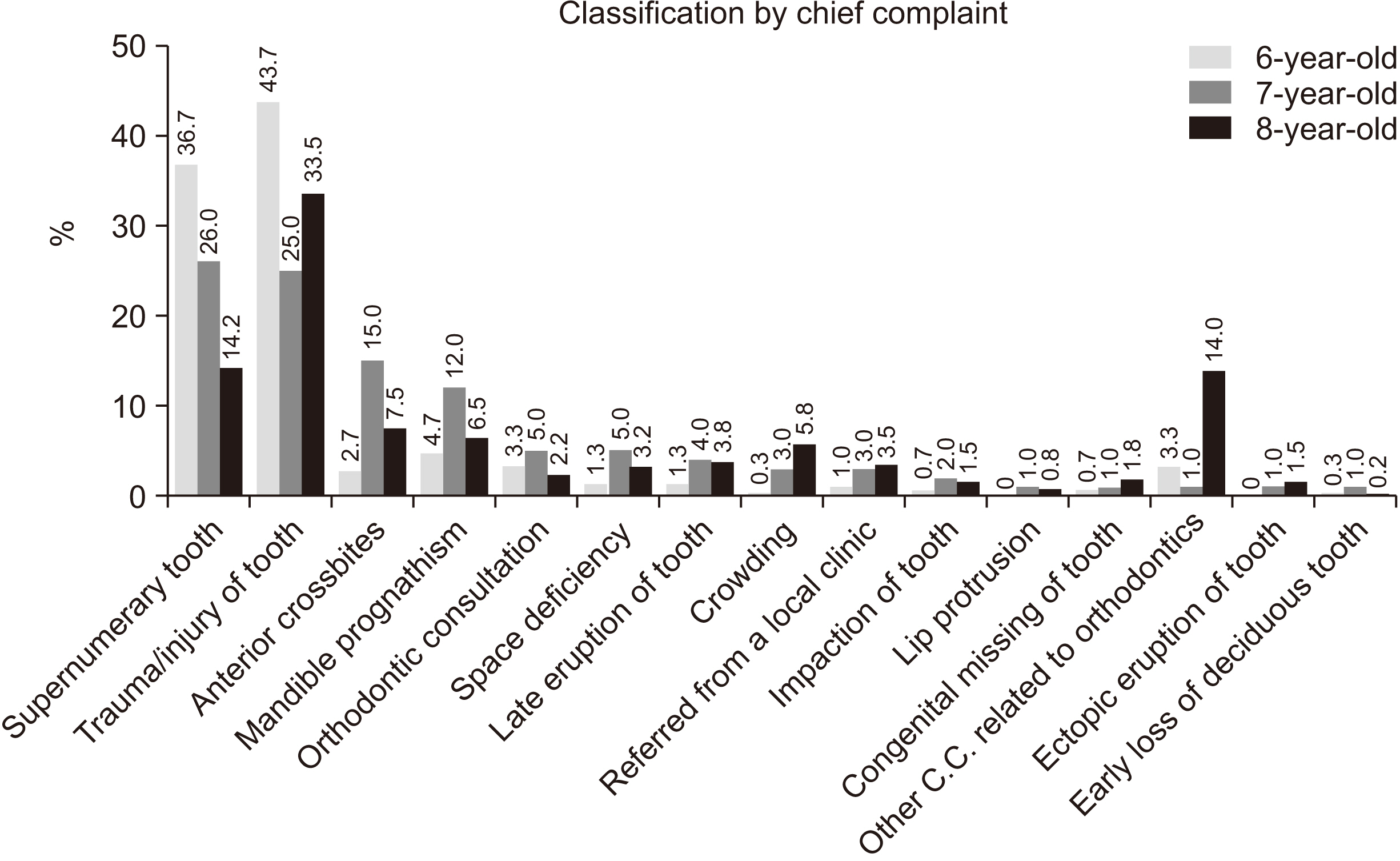

This study aimed to retrospectively analyze the prevalence of orthodontic problems and the proportion of patients who underwent orthodontic diagnosis among children aged 6 (n = 300), 7 (n = 400), and 8 (n = 400) years who had undergone panoramic radiography.

Methods

Children were divided into five groups according to their chief complaint and consultation: conservative dentistry, oral and maxillofacial surgery, orthodontics, periodontics, and prosthodontics). Chief complaints investigated included first molar eruption, lack of space for incisor eruption, frequency of eruption problems, lack of space, impaction, supernumerary teeth (SNT), missing teeth, and ectropion eruption. The number of patients whose chief complaint was not related to orthodontics but had dental problems requiring orthodontic treatment was counted. The proportion of patients with orthodontic problems who received an orthodontic diagnosis was also examined.

Results

Dental trauma and SNT were the most frequent chief complaints among the children. The proportion of patients with orthodontic problems increased with age. However, the orthodontic diagnosis rates based on panoramic radiographs among children aged 6, 7, 8 years were only 1.5% (6 years) and 23% (7 and 8 years).

Conclusions

Accurate information should be provided to patient caregivers to correct misconceptions regarding the appropriateness of delaying orthodontic examination until permanent dentition is established.

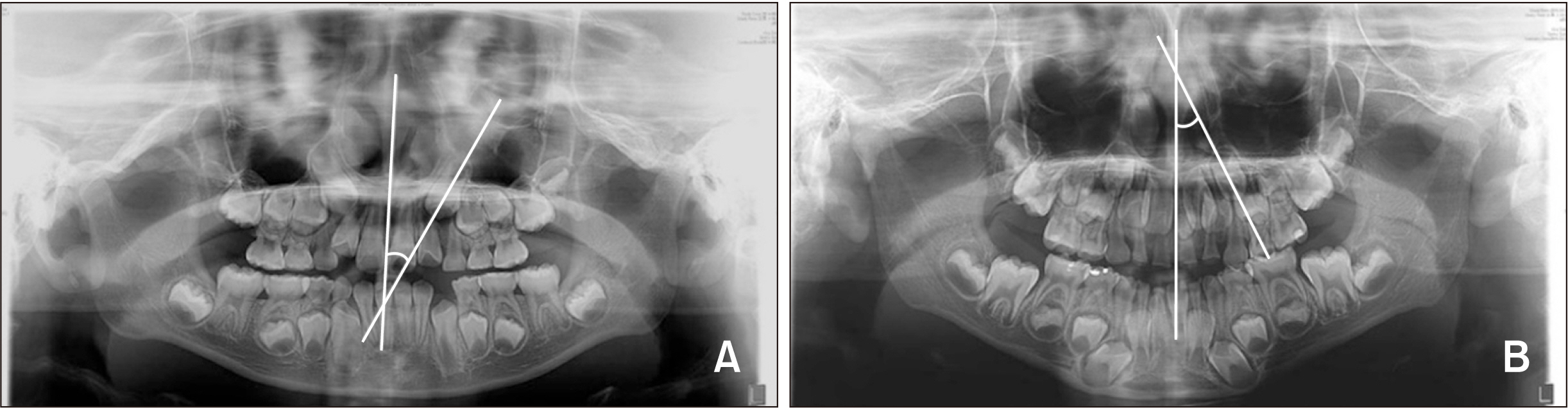

Figure

Reference

-

1. Grippaudo MM, Quinzi V, Manai A, Paolantonio EG, Valente F, La Torre G, et al. 2020; Orthodontic treatment need and timing: assessment of evolutive malocclusion conditions and associated risk factors. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 21:203–8. https://doi.org/10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.03.09.2. Van Der Linden FPGM. 1990. Problems and procedures in dentofacial orthopedics (Van Der Linden series). Quintessence Publishing Co., Ltd.;Chicago: https://www.amazon.com/Problems-Procedures-Dentofacial-Orthopedics-LINDEN/dp/0867152125.3. Tausche E, Luck O, Harzer W. 2004; Prevalence of malocclusions in the early mixed dentition and orthodontic treatment need. Eur J Orthod. 26:237–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/26.3.237. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/26.3.237. PMID: 15222706.4. Lombardo G, Vena F, Negri P, Pagano S, Barilotti C, Paglia L, et al. 2020; Worldwide prevalence of malocclusion in the different stages of dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 21:115–22. https://doi.org/10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.02.05.5. De Ridder L, Aleksieva A, Willems G, Declerck D, Cadenas de Llano-Pérula M. 2022; Prevalence of orthodontic malocclusions in healthy children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19:7446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127446. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19127446. PMID: 35742703. PMCID: PMC9223594.6. Egić B. 2022; Prevalence of orthodontic malocclusion in schoolchildren in Slovenia. A prospective aepidemiological study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 23:39–43. https://doi.org/10.23804/ejpd.2022.23.01.07.7. Kathariya MD, Nikam AP, Chopra K, Patil NN, Raheja H, Kathariya R. 2013; Prevalence of dental anomalies among school going children in India. J Int Oral Health. 5:10–4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24324298/. DOI: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1395. PMID: 24309359. PMCID: PMC3845278.8. Lee JH, Yang BH, Lee SM, Kim YH, Shim HW, Chung HS. 2011; A study on the prevalence of dental anomalies in Korean dental-patients. Korean J Orthod. 41:346–53. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2011.41.5.346. DOI: 10.4041/kjod.2011.41.5.346.9. Bilge NH, Yeşiltepe S, Törenek Ağırman K, Çağlayan F, Bilge OM. 2018; Investigation of prevalence of dental anomalies by using digital panoramic radiographs. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 77:323–8. https://doi.org/10.5603/FM.a2017.0087. DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0087. PMID: 28933802.10. Eliacik BK, Atas C, Polat GG. 2021; Prevalence and patterns of tooth agenesis among patients aged 12-22 years: a retrospective study. Korean J Orthod. 51:355–62. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2021.51.5.355. DOI: 10.4041/kjod.2021.51.5.355. PMID: 34556590. PMCID: PMC8461387.11. Baron C, Houchmand-Cuny M, Enkel B, Lopez-Cazaux S. 2018; Prevalence of dental anomalies in French orthodontic patients: a retrospective study. Arch Pediatr. 25:426–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2018.07.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.arcped.2018.07.002. PMID: 30249487.12. Dang HQ, Constantine S, Anderson PJ. 2017; The prevalence of dental anomalies in an Australian population. Aust Dent J. 62:161–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12443. DOI: 10.1111/adj.12443. PMID: 27471093.13. Keski-Nisula K, Lehto R, Lusa V, Keski-Nisula L, Varrela J. 2003; Occurrence of malocclusion and need of orthodontic treatment in early mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 124:631–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.02.001. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.02.001. PMID: 14666075.14. McNamara JA Jr. 2002; Early intervention in the transverse dimension: is it worth the effort? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 121:572–4. https://doi.org/10.1067/mod.2002.124167. DOI: 10.1067/mod.2002.124167. PMID: 12080303.15. Lee JB, Jang CH, Kim CC, Hahn SH, Lee SH. 2007; Eruption disturbances of teeth in Korean children. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 34:13–8. https://journal.kapd.org/journal/view.php?number=30.16. Baccetti T. 2000; Tooth anomalies associated with failure of eruption of first and second permanent molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 118:608–10. https://doi.org/10.1067/mod.2000.97938. DOI: 10.1067/mod.2000.97938. PMID: 11113793.17. Fardi A, Kondylidou-Sidira A, Bachour Z, Parisis N, Tsirlis A. 2011; Incidence of impacted and supernumerary teeth-a radiographic study in a North Greek population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 16:e56–61. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.16.e56. DOI: 10.4317/medoral.16.e56. PMID: 20711166.18. Lee YS, Kim JW, Lee SH. 1999; A study of the correlation between the features of mesiodens and complications. J Korean Acad Pediatr Dent. 26:275–83. https://journal.kapd.org/journal/view.php?number=1101.19. Patil S, Maheshwari S. 2014; Prevalence of impacted and supernumerary teeth in the North Indian population. J Clin Exp Dent. 6:e116–20. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.51284. DOI: 10.4317/jced.51284. PMID: 24790709. PMCID: PMC4002339.20. Jang DH, Chae YK, Lee KE, Nam OH, Lee HS, Choi SC, et al. 2023; Determination of the range of intervention timing for supernumerary teeth using the Korean health insurance review and assessment service database. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 47:67–73. https://doi.org/10.22514/jocpd.2022.036. DOI: 10.22514/jocpd.2022.036.21. Kindelan SA, Day PF, Kindelan JD, Spencer JR, Duggal MS. 2008; Dental trauma: an overview of its influence on the management of orthodontic treatment. Part 1. J Orthod. 35:68–78. https://doi.org/10.1179/146531207225022482. DOI: 10.1179/146531207225022482. PMID: 18525070.22. Sastri MR, Tanpure VR, Palagi FB, Shinde SK, Ladhe K, Polepalle T. 2015; Study of the knowledge and attitude about principles and practices of orthodontic treatment among general dental practitioners and non-orthodontic specialties. J Int Oral Health. 7:44–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25878478/. PMID: 25878478. PMCID: PMC4385725.23. Lee SJ, Suhr CH. 1994; Recognition of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need of 7~18 year-old Korean adolescent. Korean J Orthod. 24:367–94. https://www.koreamed.org/SearchBasic.php?RID=2271388.24. Yang WS. 1995; The study on the orthodontic patients who visited department of orthodontics, Seoul National University Hospital during last 10 years (1985-1994). Korean J Orthod. 25:497–509. https://e-kjo.org/journal/view.html?uid=1274&vmd=Full.25. Yu HS, Ryu YK, Lee JY. 1999; A study on the distributions and trends in malocclusion patients from department of orthodontics, college of dentistry, Yonsei University. Korean J Orthod. 29:267–76. https://e-kjo.org/journal/view.html?volume=29&number=2&spage=267.26. Fernandez CCA, Pereira CVCA, Luiz RR, Vieira AR, De Castro Costa M. 2018; Dental anomalies in different growth and skeletal malocclusion patterns. Angle Orthod. 88:195–201. https://doi.org/10.2319/071917-482.1. DOI: 10.2319/071917-482.1. PMID: 29215300. PMCID: PMC8312537.27. Zou J, Meng M, Law CS, Rao Y, Zhou X. 2018; Common dental diseases in children and malocclusion. Int J Oral Sci. 10:7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-018-0012-3. DOI: 10.1038/s41368-018-0012-3. PMID: 29540669. PMCID: PMC5944594.28. Ku JH, Han B, Kim J, Oh J, Kook YA, Kim Y. 2022; Common dental anomalies in Korean orthodontic patients: an update. Korean J Orthod. 52:324–33. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod21.280. DOI: 10.4041/kjod21.280. PMID: 35844099. PMCID: PMC9512625.29. Warkhandkar A, Habib L. 2023; Effects of premature primary tooth loss on midline deviation and asymmetric molar relationship in the context of orthodontic treatment. Cureus. 15:e42442. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.42442. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.42442. PMID: 37637675. PMCID: PMC10449235.30. Gupta KP, Garg S, Grewal PS. 2011; Establishing a diagnostic tool for assessing optimal treatment timing in Indian children with developing malocclusions. J Clin Exp Dent. 3:e18–24. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.3.e18. DOI: 10.4317/jced.3.e18.31. Bedoya MM, Park JH. 2009; A review of the diagnosis and management of impacted maxillary canines. J Am Dent Assoc. 140:1485–93. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0099. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0099. PMID: 19955066.32. Jain S, Debbarma S. 2019; Patterns and prevalence of canine anomalies in orthodontic patients. Med Pharm Rep. 92:72–8. https://doi.org/10.15386/cjmed-907. DOI: 10.15386/cjmed-907. PMID: 30957090. PMCID: PMC6448493.33. Sigler LM, Baccetti T, McNamara JA Jr. 2011; Effect of rapid maxillary expansion and transpalatal arch treatment associated with deciduous canine extraction on the eruption of palatally displaced canines: a 2-center prospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 139:e235–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.07.015. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.07.015. PMID: 21392667.34. Karaiskos N, Wiltshire WA, Odlum O, Brothwell D, Hassard TH. 2005; Preventive and interceptive orthodontic treatment needs of an inner-city group of 6- and 9-year-old Canadian children. J Can Dent Assoc. 71:649. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16271161/. PMID: 16271161.35. Shalish M, Gal A, Brin I, Zini A, Ben-Bassat Y. 2013; Prevalence of dental features that indicate a need for early orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod. 35:454–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjs011. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cjs011. PMID: 22467567.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Analysis of the Prevalence of Taurodont Deciduous Molars in Children

- Evaluation of Skeletal and Dental Maturity in Relation to Vertical Facial Types and the Sex of Growing Children

- A deep learning approach to permanent tooth germ detection on pediatric panoramic radiographs

- Prediction of osteoporosis using fractal analysis on periapical and panoramic radiographs

- Comparison of panoramic radiography and cone-beam computed tomography for assessing radiographic signs indicating root protrusion into the maxillary sinus