Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2024 May;17(2):160-167. 10.21053/ceo.2024.00025.

Level of Contamination of Positive Airway Pressure Devices Used in Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Chung-Ang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Applied Statistics, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2556006

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2024.00025

Abstract

Objectives

. No study has yet evaluated the degree of contamination after the total disassembly of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices. We investigated the extent of contamination of CPAP devices used daily by patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) by disassembling the systems and identifying the factors that influenced the degree of CPAP contamination.

Methods

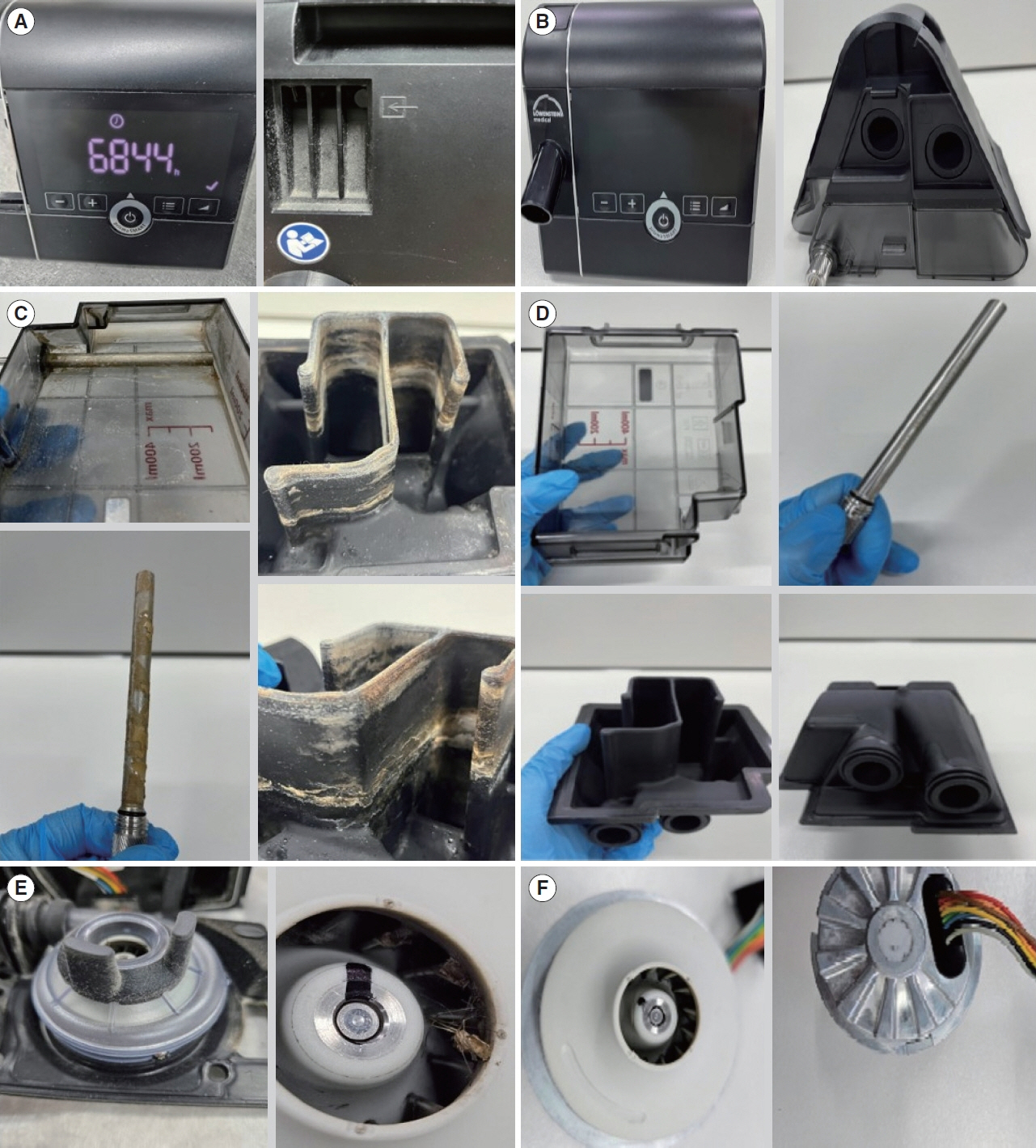

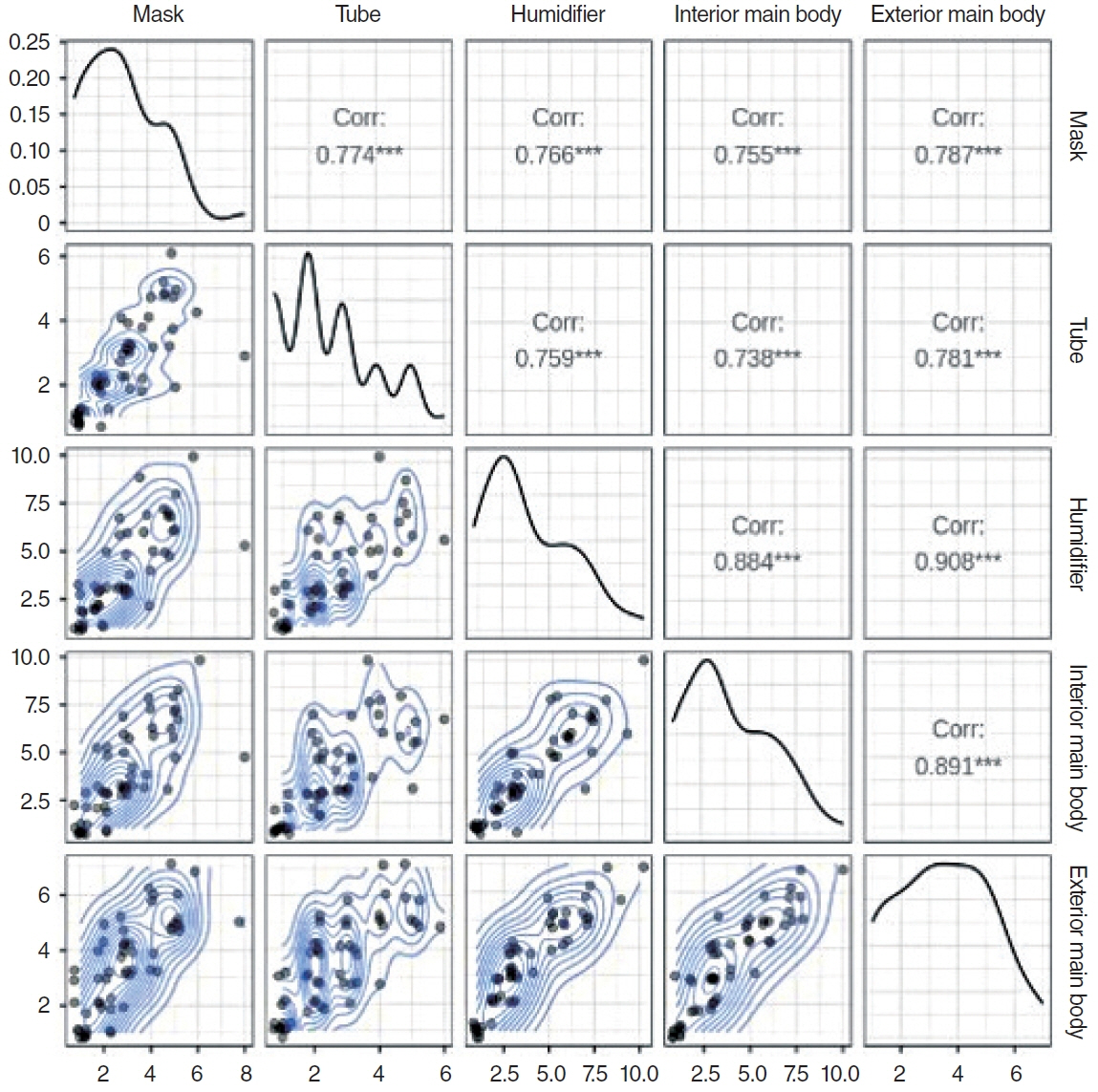

. We conducted a chart review of the medical records of patients with OSA for whom the CPAP devices were disassembled and cleaned. Two skilled technicians photographed the levels of contamination of each component and scored them using a visual analog scale. Patients’ clinical characteristics and records of CPAP device usage were statistically analyzed to identify characteristics that were significantly associated with the degree of CPAP device contamination.

Results

. Among the 55 participants, both the external components, including the mask and tube, and the internal components, such as the humidifier and the interior of the main body, showed a substantial degree of contamination. The total and average daily duration of usage of the CPAP device did not show significant associations with the degree of contamination. Age was most consistently associated with the degree of contamination, such as in masks, humidifiers, and interior and exterior main parts. The degree of contamination of the internal components of the device was significantly correlated with the degree of contamination of the external components.

Conclusion

. Age-specific guidelines for managing the hygiene of external and internal CPAP components should be prepared.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hetzel J, Herb S, Hetzel M, Rusteberg T, Kleiser G, Weber J, et al. Microbiological studies of a nasal positive pressure respirator with and without a humidifier system. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1996; 146(13-14):354–6.2. Strollo PJ Jr, Rogers RM. Obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 1996; Jan. 334(2):99–104.

Article3. Golbin JM, Somers VK, Caples SM. Obstructive sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008; Feb. 5(2):200–6.

Article4. Lenk C, Messbacher ME, Abel J, Mueller SK, Mantsopoulos K, Gostian AO, et al. The influence of obstructive sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on the nasal microbiome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023; Mar. 27(6):2605–18.5. Chin CJ, George C, Lannigan R, Rotenberg BW. Association of CPAP bacterial colonization with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013; Aug. 9(8):747–50.

Article6. Aydin E, Hizal E, Akkuzu B, Azap O. Risk of contamination of nasal sprays in otolaryngologic practice. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2007; Mar. 7:2.

Article7. Lee JM, Nayak JV, Doghramji LL, Welch KC, Chiu AG. Assessing the risk of irrigation bottle and fluid contamination after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010; May-Jun. 24(3):197–9.

Article8. Stolk JM, Russcher A, van Elzakker EP, Schippers EF. Legionella pneumonia after the use of CPAP equipment. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2016; 160:A9855.9. Steinhauer K, Goroncy-Bermes P. Investigation of the hygienic safety of continuous positive airways pressure devices after reprocessing. J Hosp Infect. 2005; Oct. 61(2):168–75.

Article10. Sanner BM, Fluerenbrock N, Kleiber-Imbeck A, Mueller JB, Zidek W. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on infectious complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Respiration. 2001; 68(5):483–7.

Article11. Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MS, Morrell MJ, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019; Aug. 7(8):687–98.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Massive REM Rebound on Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- The Role of Endothelin-1 in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Pulmonary Hypertension

- CPAP Treatment in Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- A Sleepy Man with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Obstructive Sleep Apnea Overlap Syndrome

- Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Positive Pressure Ventilation