J Korean Med Sci.

2024 May;39(19):e156. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e156.

Anchorage Dependence and Cancer Metastasis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pharmacology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Woo Choo Lee Institute for Precision Drug Development, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Biochemistry, College of Life Science and Biotechnology, Brain Korea 21 Project, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 4Graduate School of Medical Science, Brain Korea 21 Project, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2555912

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e156

Abstract

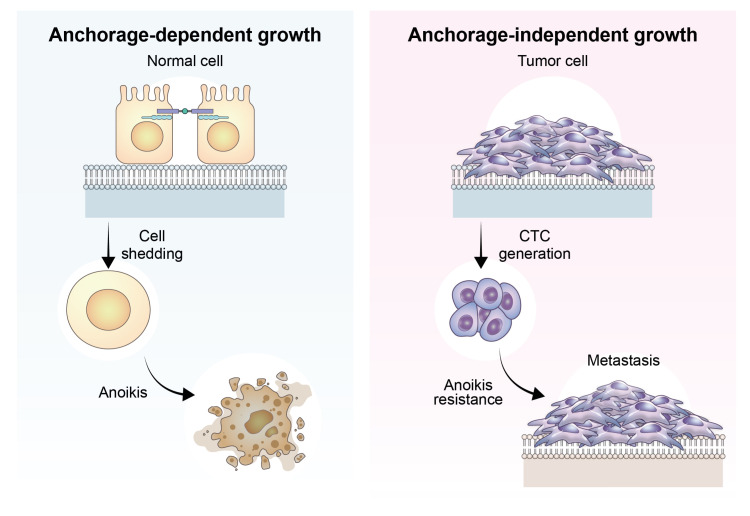

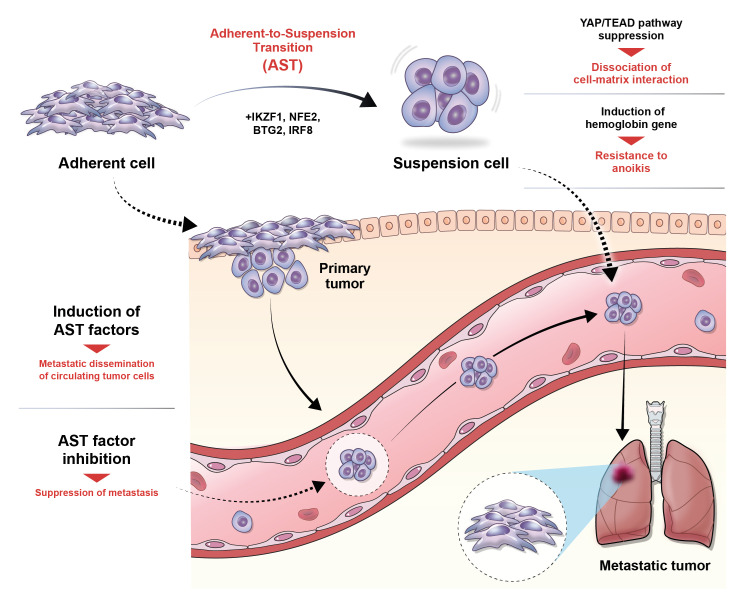

- The process of cancer metastasis is dependent on the cancer cells’ capacity to detach from the primary tumor, endure in a suspended state, and establish colonies in other locations. Anchorage dependence, which refers to the cells’ reliance on attachment to the extracellular matrix (ECM), is a critical determinant of cellular shape, dynamics, behavior, and, ultimately, cell fate in nonmalignant and cancer cells. Anchorage-independent growth is a characteristic feature of cells resistant to anoikis, a programmed cell death process triggered by detachment from the ECM. This ability to grow and survive without attachment to a substrate is a crucial stage in the progression of metastasis. The recently discovered phenomenon named “adherent-to-suspension transition (AST)” alters the requirement for anchoring and enhances survival in a suspended state. AST is controlled by four transcription factors (IKAROS family zinc finger 1, nuclear factor erythroid 2, BTG anti-proliferation factor 2, and interferon regulatory factor 8) and can detach cells without undergoing the typical epithelialmesenchymal transition. Notably, AST factors are highly expressed in circulating tumor cells compared to their attached counterparts, indicating their crucial role in the spread of cancer. Crucially, the suppression of AST substantially reduces metastasis while sparing primary tumors. These findings open up possibilities for developing targeted therapies that inhibit metastasis and emphasize the importance of AST, leading to a fundamental change in our comprehension of how cancer spreads.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Coman DR. Decreased mutual adhesiveness, a property of cells from squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1944; 4(10):625–629.2. Weiss L. Studies on cellular adhesion in tissue culture: VII. Surface activity and cell detachment. Exp Cell Res. 1964; 33(1-2):277–288. PMID: 14109141.3. Weiss L, Ward PM. Cell detachment and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1983; 2(2):111–127. PMID: 6352010.4. Engell HC. Cancer cells in the circulating blood; a clinical study on the occurrence of cancer cells in the peripheral blood and in venous blood draining the tumour area at operation. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1955; 201:1–70. PMID: 14387468.5. Ashworth T. A case of cancer in which cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after death. Aust Med J. 1869; 14:146–147.6. Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976; 194(4260):23–28. PMID: 959840.7. Frisch SM, Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994; 124(4):619–626. PMID: 8106557.8. Nagrath S, Sequist LV, Maheswaran S, Bell DW, Irimia D, Ulkus L, et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature. 2007; 450(7173):1235–1239. PMID: 18097410.9. Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Challenges in circulating tumour cell research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014; 14(9):623–631. PMID: 25154812.10. Meredith JE Jr, Fazeli B, Schwartz MA. The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol Biol Cell. 1993; 4(9):953–961. PMID: 8257797.11. Ruoslahti E, Reed JC. Anchorage dependence, integrins, and apoptosis. Cell. 1994; 77(4):477–478. PMID: 8187171.12. Hawk MA, Schafer ZT. Mechanisms of redox metabolism and cancer cell survival during extracellular matrix detachment. J Biol Chem. 2018; 293(20):7531–7537. PMID: 29339552.13. Endo H, Owada S, Inagaki Y, Shida Y, Tatemichi M. Metabolic reprogramming sustains cancer cell survival following extracellular matrix detachment. Redox Biol. 2020; 36:101643. PMID: 32863227.14. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006; 126(4):663–676. PMID: 16904174.15. Wang H, Yang Y, Liu J, Qian L. Direct cell reprogramming: approaches, mechanisms and progress. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021; 22(6):410–424. PMID: 33619373.16. Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat (Basel). 1995; 154(1):8–20. PMID: 8714286.17. Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009; 119(6):1420–1428. PMID: 19487818.18. Micalizzi DS, Farabaugh SM, Ford HL. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: parallels between normal development and tumor progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010; 15(2):117–134. PMID: 20490631.19. Yang J, Antin P, Berx G, Blanpain C, Brabletz T, Bronner M, et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020; 21(6):341–352. PMID: 32300252.20. Huh HD, Sub Y, Oh J, Kim YE, Lee JY, Kim HR, et al. Reprogramming anchorage dependency by adherent-to-suspension transition promotes metastatic dissemination. Mol Cancer. 2023; 22(1):63. PMID: 36991428.21. Kim K, Kim YJ. RhoBTB3 regulates proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells via Col1a1. Mol Cells. 2022; 45(9):631–639. PMID: 35698915.22. Hamidi H, Ivaska J. Every step of the way: integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018; 18(9):533–548. PMID: 30002479.23. Raub TJ, Kuentzel SL. Kinetic and morphological evidence for endocytosis of mammalian cell integrin receptors by using an anti-fibronectin receptor beta subunit monoclonal antibody. Exp Cell Res. 1989; 184(2):407–426. PMID: 2530101.24. Caswell P, Norman J. Endocytic transport of integrins during cell migration and invasion. Trends Cell Biol. 2008; 18(6):257–263. PMID: 18456497.25. Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Coso OA, Gutkind JS, Burbelo PD, Akiyama SK, et al. Integrin function: molecular hierarchies of cytoskeletal and signaling molecules. J Cell Biol. 1995; 131(3):791–805. PMID: 7593197.26. Yamada KM, Even-Ram S. Integrin regulation of growth factor receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2002; 4(4):E75–E76. PMID: 11944037.27. Hsieh TC, Wu JM. Resveratrol suppresses prostate cancer epithelial cell scatter/invasion by targeting inhibition of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) secretion by prostate stromal cells and upregulation of E-cadherin by prostate cancer epithelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21(5):1760. PMID: 32143478.28. Cory G. Scratch-wound assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2011; 769:25–30. PMID: 21748666.29. Gough W, Hulkower KI, Lynch R, McGlynn P, Uhlik M, Yan L, et al. A quantitative, facile, and high-throughput image-based cell migration method is a robust alternative to the scratch assay. J Biomol Screen. 2011; 16(2):155–163. PMID: 21297103.30. Zicha D, Dunn GA, Brown AF. A new direct-viewing chemotaxis chamber. J Cell Sci. 1991; 99(Pt 4):769–775. PMID: 1770004.31. Zantl R, Horn E. Chemotaxis of slow migrating mammalian cells analysed by video microscopy. Methods Mol Biol. 2011; 769:191–203. PMID: 21748677.32. Boyden S. The chemotactic effect of mixtures of antibody and antigen on polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Exp Med. 1962; 115(3):453–466. PMID: 13872176.33. Falasca M, Raimondi C, Maffucci T. Boyden chamber. Methods Mol Biol. 2011; 769:87–95. PMID: 21748671.34. Bjerkvig R, Tønnesen A, Laerum OD, Backlund EO. Multicellular tumor spheroids from human gliomas maintained in organ culture. J Neurosurg. 1990; 72(3):463–475. PMID: 2406382.35. Salmaggi A, Boiardi A, Gelati M, Russo A, Calatozzolo C, Ciusani E, et al. Glioblastoma-derived tumorospheres identify a population of tumor stem-like cells with angiogenic potential and enhanced multidrug resistance phenotype. Glia. 2006; 54(8):850–860. PMID: 16981197.36. Weiswald LB, Richon S, Validire P, Briffod M, Lai-Kuen R, Cordelières FP, et al. Newly characterised ex vivo colospheres as a three-dimensional colon cancer cell model of tumour aggressiveness. Br J Cancer. 2009; 101(3):473–482. PMID: 19603013.37. Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY, Ingber DE. Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science. 2010; 328(5986):1662–1668. PMID: 20576885.38. Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RG, Van Es JH, Van den Brink S, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011; 141(5):1762–1772. PMID: 21889923.39. Cho EH, Wendel M, Luttgen M, Yoshioka C, Marrinucci D, Lazar D, et al. Characterization of circulating tumor cell aggregates identified in patients with epithelial tumors. Phys Biol. 2012; 9(1):016001. PMID: 22306705.40. Yu M, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Stott SL, Smas ME, Ting DT, et al. Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science. 2013; 339(6119):580–584. PMID: 23372014.41. Aceto N, Bardia A, Miyamoto DT, Donaldson MC, Wittner BS, Spencer JA, et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2014; 158(5):1110–1122. PMID: 25171411.42. Lin H, Hu P, Zhang H, Deng Y, Yang Z, Zhang L. GATA2-mediated transcriptional activation of Notch3 promotes pancreatic cancer liver metastasis. Mol Cells. 2022; 45(5):329–342. PMID: 35534193.43. Seal SH. Silicone flotation: a simple quantitative method for the isolation of free-floating cancer cells from the blood. Cancer. 1959; 12(3):590–595. PMID: 13652106.44. Riethdorf S, Müller V, Zhang L, Rau T, Loibl S, Komor M, et al. Detection and HER2 expression of circulating tumor cells: prospective monitoring in breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant GeparQuattro trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010; 16(9):2634–2645. PMID: 20406831.45. Lucci A, Hall CS, Patel SP, Narendran B, Bauldry JB, Royal RE, et al. Circulating tumor cells and early relapse in node-positive melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2020; 26(8):1886–1895. PMID: 32015020.46. Molnár A, Wu P, Largespada DA, Vortkamp A, Scherer S, Copeland NG, et al. The Ikaros gene encodes a family of lymphocyte-restricted zinc finger DNA binding proteins, highly conserved in human and mouse. J Immunol. 1996; 156(2):585–592. PMID: 8543809.47. Cox TC, Bawden MJ, Martin A, May BK. Human erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase: promoter analysis and identification of an iron-responsive element in the mRNA. EMBO J. 1991; 10(7):1891–1902. PMID: 2050125.48. Duriez C, Falette N, Audoynaud C, Moyret-Lalle C, Bensaad K, Courtois S, et al. The human BTG2/TIS21/PC3 gene: genomic structure, transcriptional regulation and evaluation as a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Gene. 2002; 282(1-2):207–214. PMID: 11814693.49. Hashmueli S, Gleit-Kielmanowicz M, Meraro D, Azriel A, Melamed D, Levi BZ. A truncated IFN-regulatory factor-8consensus sequence-binding protein acts as dominant-negative, interferes with endogenous protein-protein interactions and leads to apoptosis of immune cells. Int Immunol. 2003; 15(7):807–815. PMID: 12807819.50. Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011; 474(7350):179–183. PMID: 21654799.51. Park JH, Shin JE, Park HW. The role of hippo pathway in cancer stem cell biology. Mol Cells. 2018; 41(2):83–92. PMID: 29429151.52. Pearson JD, Huang K, Pacal M, McCurdy SR, Lu S, Aubry A, et al. Binary pan-cancer classes with distinct vulnerabilities defined by pro- or anti-cancer YAP/TEAD activity. Cancer Cell. 2021; 39(8):1115–1134.e12. PMID: 34270926.53. Fidler IJ. The relationship of embolic homogeneity, number, size and viability to the incidence of experimental metastasis. Eur J Cancer (1965). 1973; 9(3):223–227. PMID: 4787857.54. Liu X, Taftaf R, Kawaguchi M, Chang YF, Chen W, Entenberg D, et al. Homophilic CD44 interactions mediate tumor cell aggregation and polyclonal metastasis in patient-derived breast cancer models. Cancer Discov. 2019; 9(1):96–113. PMID: 30361447.55. Reiter JG, Makohon-Moore AP, Gerold JM, Heyde A, Attiyeh MA, Kohutek ZA, et al. Minimal functional driver gene heterogeneity among untreated metastases. Science. 2018; 361(6406):1033–1037. PMID: 30190408.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The skeletal cortical anchorage using titanium microscrew implants

- Indirect palatal skeletal anchorage (PSA) for treatment of skeletal Class I bialveolar protrusion

- The use of miniscrew as an anchorage for the orthodontic tooth movement

- Cancer Patient with Major Depressive Disorder Initially Suspected of Opioid Dependence or Abuse

- A clinical study on anchorage control of molar anchoring spring(MAS) during retraction of the maxillary canine