Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2024 May;67(3):286-295. 10.5468/ogs.23293.

Attitude toward human papillomavirus self-sampling and associated factors among Thai women undergoing colposcopy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

- 2Division of Gynaecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 3Division of Gynaecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Pathum Thani, Thailand

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital, Navamindradhiraj University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, MedPark Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand

- 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Thai Gynecologic Cancer Society, Bangkok, Thailand

- KMID: 2555512

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.23293

Abstract

Objective

To compare attitudes toward self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing before and after specimen collection in women undergoing colposcopy. The factors associated with the pre-sampling attitude were also studied.

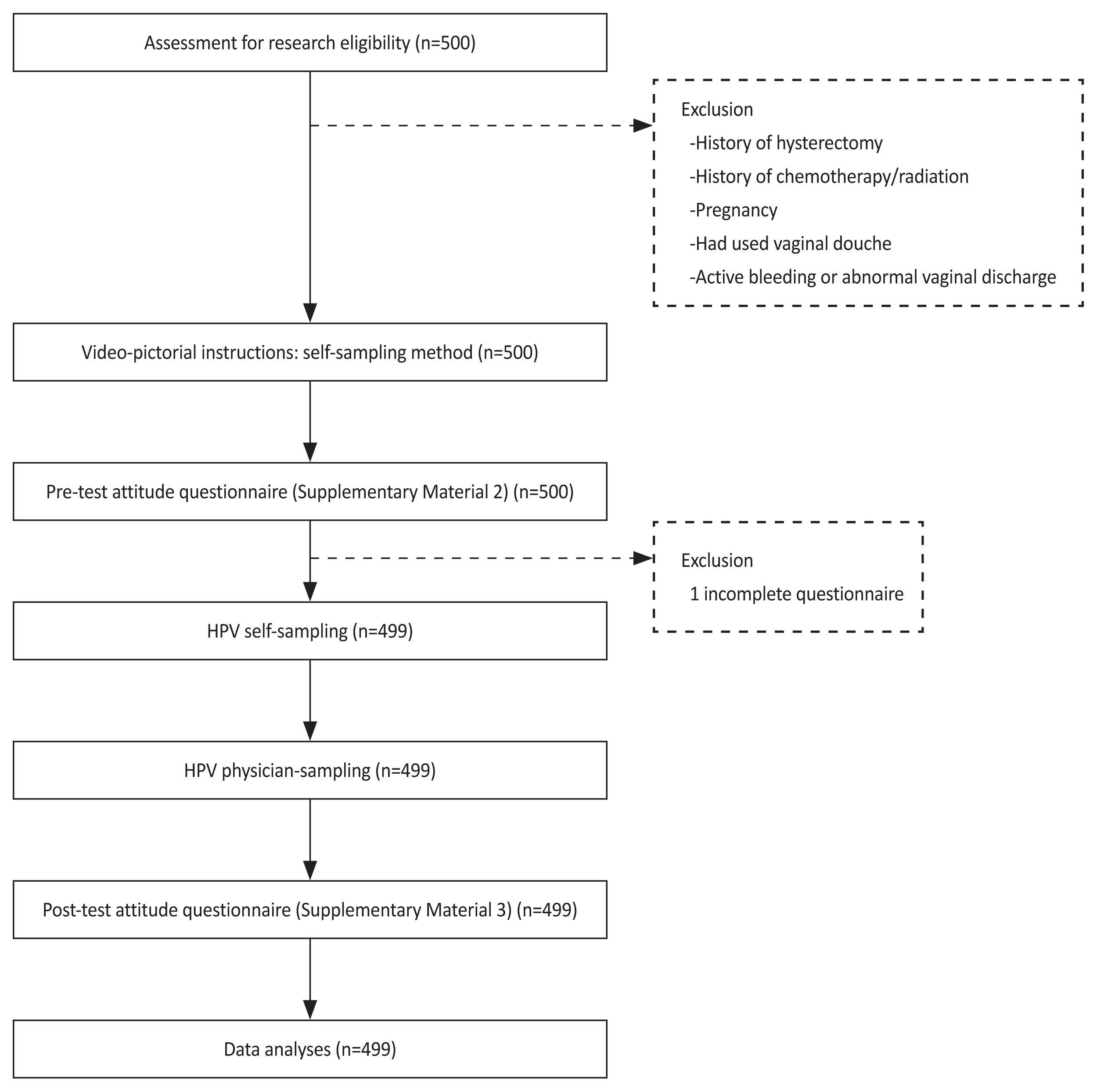

Methods

This prospective study enrolled women with abnormal cervical cytology and/or positive high-risk HPV who attended colposcopy clinics at 10 cancer centers in Thailand between October 2021 and May 2022. Prior to colposcopy, the attitudes of the women toward self-sampling were surveyed through a questionnaire. Written and verbal instructions for self-sampling were provided before the process and subsequent colposcopy. The attitudes toward self-sampling were reassessed after the actual self-sampling. Factors associated with the attitudes were analyzed.

Results

A total of 499 women were included in this study. The mean age was 39.28±11.36 years. A total of 85.3% were premenopause, and 98.8% had sexual experience. With the full score of 45, the attitude score after self-sampling was significantly higher than the attitude score before self-sampling (39.69±5.16 vs. 37.76±5.71; P<0.001). On univariate analysis, the factors associated with attitude before HPV self-sampling were age, menopausal status, sexual activity, education level, income, knowledge regarding HPV, and prior high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion histology. The remaining significant factor on multivariate analysis was sexual activity within the past year (B=0.105, 95% confidence interval, 0.014-2.870; P=0.048).

Conclusion

Attitudes toward self-sampling improved after the actual self-sampling process, as evidenced by higher attitude scores. Sexual activity was the only independent factor related to the attitude before self-sampling.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71:209–49.2. Yun BS, Park EH, Ha J, Lee JY, Lee KH, Lee TS, et al. Incidence and survival of gynecologic cancer including cervical, uterine, ovarian, vaginal, vulvar cancer and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia in Korea, 1999–2019: Korea Central Cancer Registry. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2023; 66:545–61.3. Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M, Keane A, Simms KT, Caruana M, et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020; 395:591–603.4. Vaccarella S, Lortet-Tieulent J, Plummer M, Franceschi S, Bray F. Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence: impact of screening against changes in disease risk factors. Eur J Cancer. 2013; 49:3262–73.5. Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2019; 393:169–82.6. Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, Etzioni R, Flowers CR, Herzig A, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020; 70:321–46.7. Jareemit N, Horthongkham N, Therasakvichya S, Viriyapak B, Inthasorn P, Benjapibal M, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology, and its immediate risk for high-grade cervical lesion or cancer: a single-center, cross-sectional study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022; 65:335–45.8. Khuhaprema T, Attasara P, Srivatanakul P, Sangrajrang S, Muwonge R, Sauvaget C, et al. Organization and evolution of organized cervical cytology screening in Thailand. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012; 118:107–11.9. Darlin L, Borgfeldt C, Forslund O, Hénic E, Hortlund M, Dillner J, et al. Comparison of use of vaginal HPV self-sampling and offering flexible appointments as strategies to reach long-term non-attending women in organized cervical screening. J Clin Virol. 2013; 58:155–60.10. Scarinci IC, Litton AG, Garcés-Palacio IC, Partridge EE, Castle PE. Acceptability and usability of self-collected sampling for HPV testing among African-American women living in the Mississippi Delta. Womens Health Issues. 2013; 23:e123–30.11. Szarewski A, Cadman L, Ashdown-Barr L, Waller J. Exploring the acceptability of two self-sampling devices for human papillomavirus testing in the cervical screening context: a qualitative study of Muslim women in London. J Med Screen. 2009; 16:193–8.12. Kritpetcharat O, Suwanrungruang K, Sriamporn S, Kamsa-Ard S, Kritpetcharat P, Pengsaa P. The coverage of cervical cancer screening in Khon Kaen, northeast Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2003; 4:103–5.13. Thanapprapasr D, Deesamer S, Sujintawong S, Udomsubpayakul U, Wilailak S. Cervical cancer screening behaviours among Thai women: results from a cross-sectional survey of 2112 healthcare providers at Ramathibodi Hospital, Thailand. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2012; 21:542–7.14. Chaowawanit W, Tangjitgamol S, Kantathavorn N, Phoolcharoen N, Kittisiam T, Khunnarong J, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior of bangkok metropolitan women regarding cervical cancer screening. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016; 17:945–52.15. Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Suonio E, Dillner L, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15:172–83.16. Nishimura H, Yeh PT, Oguntade H, Kennedy CE, Narasimhan M. HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening: a systematic review of values and preferences. BMJ Glob Health. 2021; 6:e003743.

Article17. Nelson EJ, Maynard BR, Loux T, Fatla J, Gordon R, Arnold LD. The acceptability of self-sampled screening for HPV DNA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017; 93:56–61.18. Kamath Mulki A, Withers M. Human papilloma virus self-sampling performance in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Womens Health. 2021; 21:12.19. Phoolcharoen N, Kantathavorn N, Krisorakun W, Taepisitpong C, Krongthong W, Saeloo S. Acceptability of self-sample human papillomavirus testing among Thai women visiting a colposcopy clinic. J Community Health. 2018; 43:611–5.20. Serrano B, Ibáñez R, Robles C, Peremiquel-Trillas P, de Sanjosé S, Bruni L. Worldwide use of HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 2022; 154:106900.21. Kittisiam T, Tangjitgamol S, Chaowawanit W, Khunnarong J, Srijaipracharoen S, Thavaramara T, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of Bangkok metropolitan women towards HPV and self-sampled HPV testing. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016; 17:2445–51.22. Wong EL, Cheung AW, Wong AY, Chan PK. Acceptability and feasibility of HPV self-sampling as an alternative primary cervical cancer screening in under-screened population groups: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17:6245.23. Trope LA, Chumworathayi B, Blumenthal PD. Feasibility of community-based careHPV for cervical cancer prevention in rural Thailand. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013; 17:315–9.24. De Pauw H, Donders G, Weyers S, De Sutter P, Doyen J, Tjalma WAA, et al. Cervical cancer screening using HPV tests on self-samples: attitudes and preferences of women participating in the VALHUDES study. Arch Public Health. 2021; 79:155.25. Oranratanaphan S, Termrungruanglert W, Khemapech N. Acceptability of self-sampling HPV testing among Thai women for cervical cancer screening. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014; 15:7437–41.26. Kraut RY, Manca D, Lofters A, Hoffart K, Khan U, Liu S, et al. Attitudes toward human papillomavirus self-sampling in regularly screened women in edmonton, Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2021; 25:199–204.

Article27. Oranratanaphan S, Amatyakul P, Iramaneerat K, Srithipayawan S. Knowledge, attitudes and practices about the Pap smear among medical workers in Naresuan University Hospital, Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010; 11:1727–30.28. Chen SL, Hsieh PC, Chou CH, Tzeng YL. Determinants of women’s likelihood of vaginal self-sampling for human papillomavirus to screen for cervical cancer in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2014; 14:139.29. Likitdee N, Kietpeerakool C, Chumworathayi B, Temtanakitpaisan A, Aue-Aungkul A, Nhokaew W, et al. Knowledge and attitude toward human papillomavirus infection and vaccination among Thai women: a nationwide social media survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020; 21:2895–902.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Factors influencing Human Papillomavirus Vaccination intention in Female High School Students: Application of Planned Behavior Theory

- Detection of Human Papillomavius DNA by Hybrid Capture Test in Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Carcinoma

- Epidemiology, prevention and treatment of cervical cancer in the Philippines

- Factors Associated with Intention to receive Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Undergraduate Women: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior

- Colposcopy at a turning point