J Korean Med Sci.

2024 May;39(17):e145. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e145.

Trends of Gaps Between HealthAdjusted Life Expectancy and Life Expectancy at the Regional Level in Korea Using a Group-Based Multi-Trajectory Modeling Approach (2008–2019)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Public Health, Graduate School of Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Transdisciplinary Major in Learning Health Systems, Department of Healthcare Sciences, Graduate School, Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Artificial Intelligence and Big-Data Convergence Center, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

- 4Department of Big Data Strategy, National Health Insurance Service, Wonju, Korea

- 5Department of Preventive Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

- 6Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Preventive Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Graduate School of Public Health, Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- 9Institute for Future Public Health, Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2555495

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e145

Abstract

- Background

Health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) is an indicator of the average lifespan in good health. Through this study, we aimed to identify regional disparities in the gap between HALE and life expectancy, considering the trends that have changed over time in Korea.

Methods

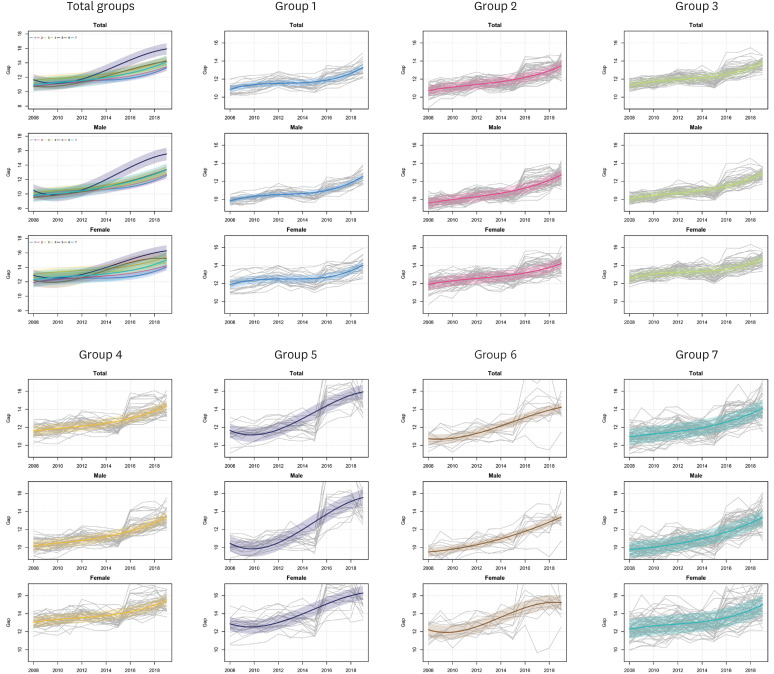

We employed a group-based multi-trajectory modeling approach to capture trends in the gap between HALE and life expectancy at the regional level from 2008 to 2019. HALE was calculated using incidence-based “years lived with disability.” This methodology was also employed in the Korean National Burden of Disease Study.

Results

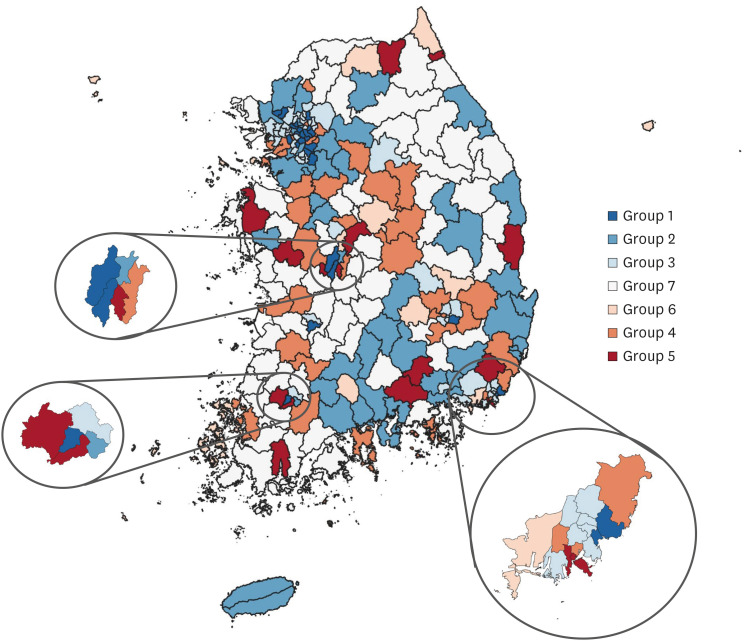

Based on five different information criteria, the most fitted number of trajectory groups was seven, with at least 11 regions in each group. Among the seven groups, one had an exceptionally large gap between HALE and life expectancy compared to that of the others. This group was assigned to 17 regions, of which six were metropolitan cities.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, we identified regions in which health levels have deteriorated over time, particularly within specific areas of metropolitan cities. These findings can be used to design comprehensive policy interventions for community health promotion and urban regeneration projects in the future.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD, Li G, Foreman K, Ezzati M. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet. 2017; 389(10076):1323–1335. PMID: 28236464.2. Jaba E, Balan C, Robu IB. The assessment of health care system performance based on the variation of life expectancy. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013; 81:162–166.3. Beltrán-Sánchez H, Soneji S, Crimmins EM. Past, present, and future of healthy life expectancy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015; 5(11):a025957. PMID: 26525456.4. GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018; 392(10159):1859–1922. PMID: 30415748.5. Jo MW, Seo W, Lim SY, Ock M. The trends in health life expectancy in Korea according to age, gender, education level, and subregion: using quality-adjusted life expectancy method. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(Suppl 1):e88. PMID: 30923491.6. Kim K, Jeon S. A study on the health adjusted life expectancy in Korea using microdata of National Health Insurance Service. Korea J Popul Stud. 2022; 45(4):25–42.7. Kim YE, Jung YS, Ock M, Park H, Kim KB, Go DS, et al. The gaps in health-adjusted life years (HALE) by income and region in Korea: a national representative bigdata analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3473. PMID: 33801588.8. Kim YE, Jung YS, Ock M, Yoon SJ. A review of the types and characteristics of healthy life expectancy and methodological issues. J Prev Med Public Health. 2022; 55(1):1–9. PMID: 35135043.9. Lee JY, Ock M, Kim SH, Go DS, Kim HJ, Jo MW. Health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) in Korea: 2005–2011. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31 (Suppl 2):Suppl 2. S139–S145. PMID: 27775251.10. Lim D, Bahk J, Ock M, Kim I, Kang HY, Kim YY, et al. Income-related inequality in quality-adjusted life expectancy in Korea at the national and district levels. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020; 18(1):45. PMID: 32103763.11. Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011; 32(1):381–398. PMID: 21091195.12. Theodore H, Tulcinsdy EA. Measuring, monitoring and evaluating the health of a population. 2014; 91–147.13. Cho K. Changes in infectious diseases, health behaviors, and medical uses during COVID-19 pandemic in the Republic of Korea 2020. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2021; 39(39):2750–2764.14. Jung YS, Kim YE, Park H, Oh IH, Jo MW, Ock M, et al. Measuring the burden of disease in Korea, 2008–2018. J Prev Med Public Health. 2021; 54(5):293–300. PMID: 34649391.15. Kim YE, Park H, Jo MW, Oh IH, Go DS, Jung J, et al. Trends and patterns of burden of disease and injuries in Korea using disability-adjusted life years. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34(Suppl 1):e75. PMID: 30923488.16. Nagin DS, Jones BL, Passos VL, Tremblay RE. Group-based multi-trajectory modeling. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018; 27(7):2015–2023. PMID: 29846144.17. Sun C, Xi F, Li J, Yu W, Wang X. Longitudinal D-dimer trajectories and the risk of mortality in abdominal trauma patients: a group-based trajectory modeling analysis. J Clin Med. 2023; 12(3):1091. PMID: 36769738.18. Magrini A. Assessment of agricultural sustainability in European Union countries: a group-based multivariate trajectory approach. AStA Adv Stat Anal. 2022; 106(4):673–703.19. Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent Curve Models: A Structural Equation Perspective. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons;2006.20. Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010; 6(1):109–138. PMID: 20192788.21. Lee HM, Ko H. The impact of benefits coverage expansion of social health insurance: evidence from Korea. Health Policy. 2022; 126(9):925–932. PMID: 35817628.22. Kim D, Kim YE, Lee SY, Suh JH, Kim JH. The Effect of Increased Health Care Coverage on Provider Behavior in Cancer Care. Sejong, Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2016. p. 1–252.23. Lee E. Current issues and policy directions for the national health insurance. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2018; 256:51–64.24. Jung YS, Yoon SJ. Trends and patterns of cancer burdens by region and income level in Korea: a national representative big data analysis. Cancer Res Treat. 2023; 55(2):408–418. PMID: 36097805.25. Seo JK, Cho M, Skelton T. ‘Dynamic Busan’: envisioning a global hub city in Korea. Cities. 2015; 46:26–34.26. Lee JS, Ha SY, Kwon YW. A study on the characteristics of architectural assets in Daejeon metropolitan city. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2020; 21(7):224–232.27. Mijs JJ, Roe EL. Is America coming apart? Socioeconomic segregation in neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, and social networks, 1970–2020. Sociol Compass. 2021; 15(6):e12884.28. Ross NA, Nobrega K, Dunn J. Income segregation, income inequality and mortality in North American metropolitan areas. GeoJournal. 2001; 53(2):117–124.29. André Hutson M, Kaplan GA, Ranjit N, Mujahid MS. Metropolitan fragmentation and health disparities: is there a link? Milbank Q. 2012; 90(1):187–207. PMID: 22428697.30. Do DP, Frank R, Iceland J. Black-white metropolitan segregation and self-rated health: investigating the role of neighborhood poverty. Soc Sci Med. 2017; 187:85–92. PMID: 28667834.31. Jung YS, Kim YE, Ock M, Yoon SJ. Measuring the burden of disease in Korea using disability-adjusted life years (2008-2020). J Korean Med Sci. 2024; 39(7):e67. PMID: 38412612.32. Jung YS, Kim YE, Ock M, Yoon SJ. Trends in healthy life expectancy (HALE) and disparities by income and region in Korea (2008–2020): analysis of a nationwide claims database. J Korean Med Sci. 2024; 39(6):e46. PMID: 38374624.33. Lee JH, Lee MH. Regional balanced development policy leverage in the capital and noncapital areas: focusing on local function concentration and dispersion structure. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2019; 20(12):502–512.34. Park JH, Oh JH, Kang JG, Jeong YJ, Lee KS. Relationship between the level of local extinction and total medical service uses. Health Policy Manag. 2023; 33(3):253–263.35. Kim YE, Lee JS, Kim S. Proposing the classification matrix for growing and shrinking cities: a case study of 228 districts in South Korea. Habitat Int. 2022; 127:102644.36. Lee BH. A study on classification of downtown areas based on small and medium cities in Korea. Kawakami M, Shen ZJ, Pai JT, Gao XL, Zhang M, editors. Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development: Approaches for Achieving Sustainable Urban Form in Asian Cities. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer;2013. p. 33–49.37. Ko M, Kim K. Analyses on the changes in the spatial distribution of Korean local extinction risk. J Korean Cartographic Assoc. 2021; 21(1):65–74.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Income gaps in self-rated poor health and its association with life expectancy in 245 districts of Korea

- Life Expectancy of The Posttraumatic Persistent Vegetative State: Review of Literature and A Proposal

- A Review of the Types and Characteristics of Healthy Life Expectancy and Methodological Issues

- An Expert Opinion on the Life Expectancy after Traumatic Brain Injury

- Estimation of the Life Expectancy for The disabled Persons after Head Injury