Cancer Res Treat.

2024 Apr;56(2):380-403. 10.4143/crt.2023.650.

Health Inequities in Cancer Incidence According to Economic Status and Regions Are Still Existed Even under Universal Health Coverage System in Korea: A Nationwide Population Based Study Using the National Health Insurance Database

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2HIRA Research Institute, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, Wonju, Korea

- 3Department of Family Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Public Healthcare Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2554330

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2023.650

Abstract

- Purpose

The purpose of this study is to determine the level of health equity in relation to cancer incidence.

Materials and Methods

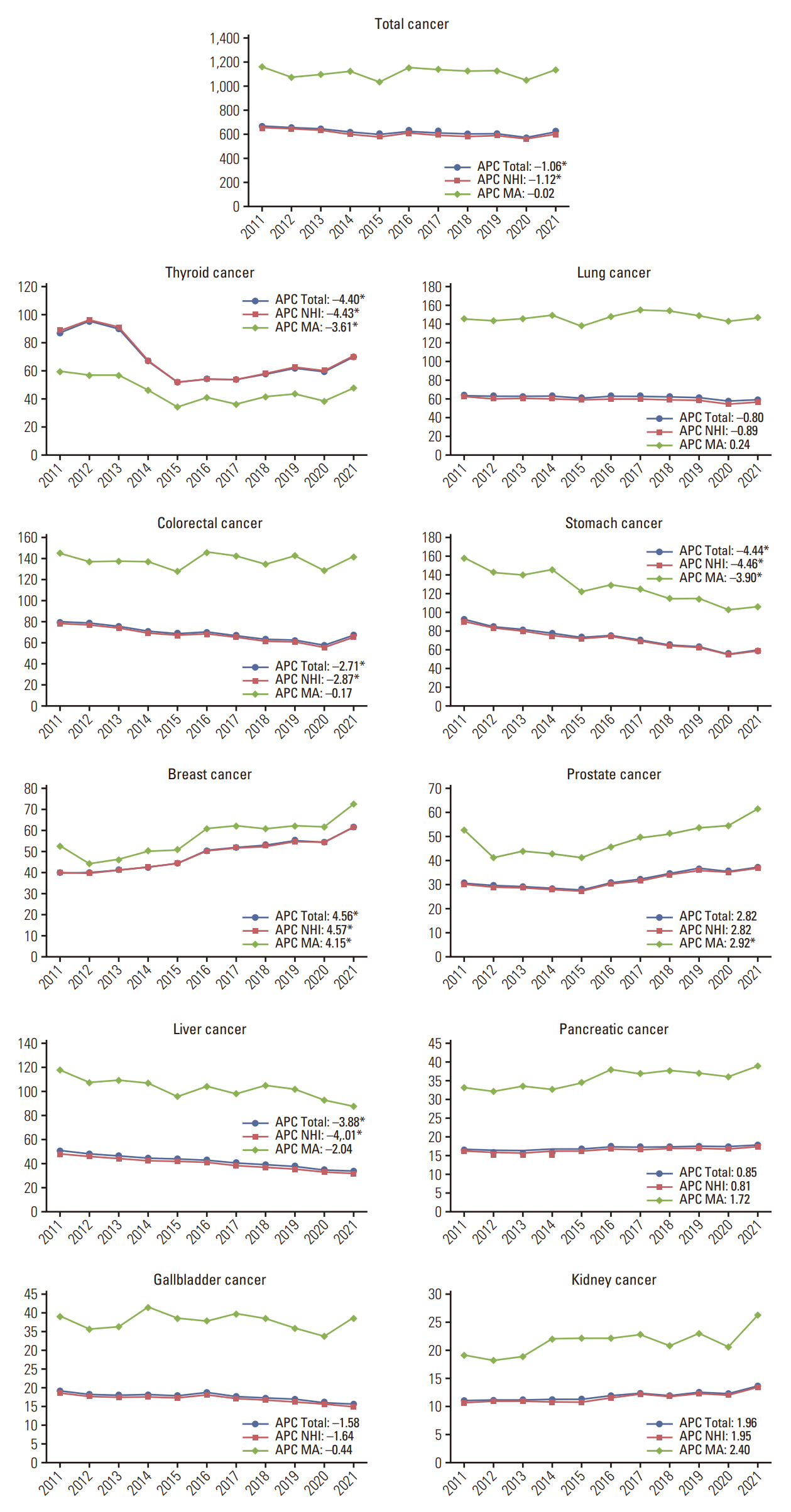

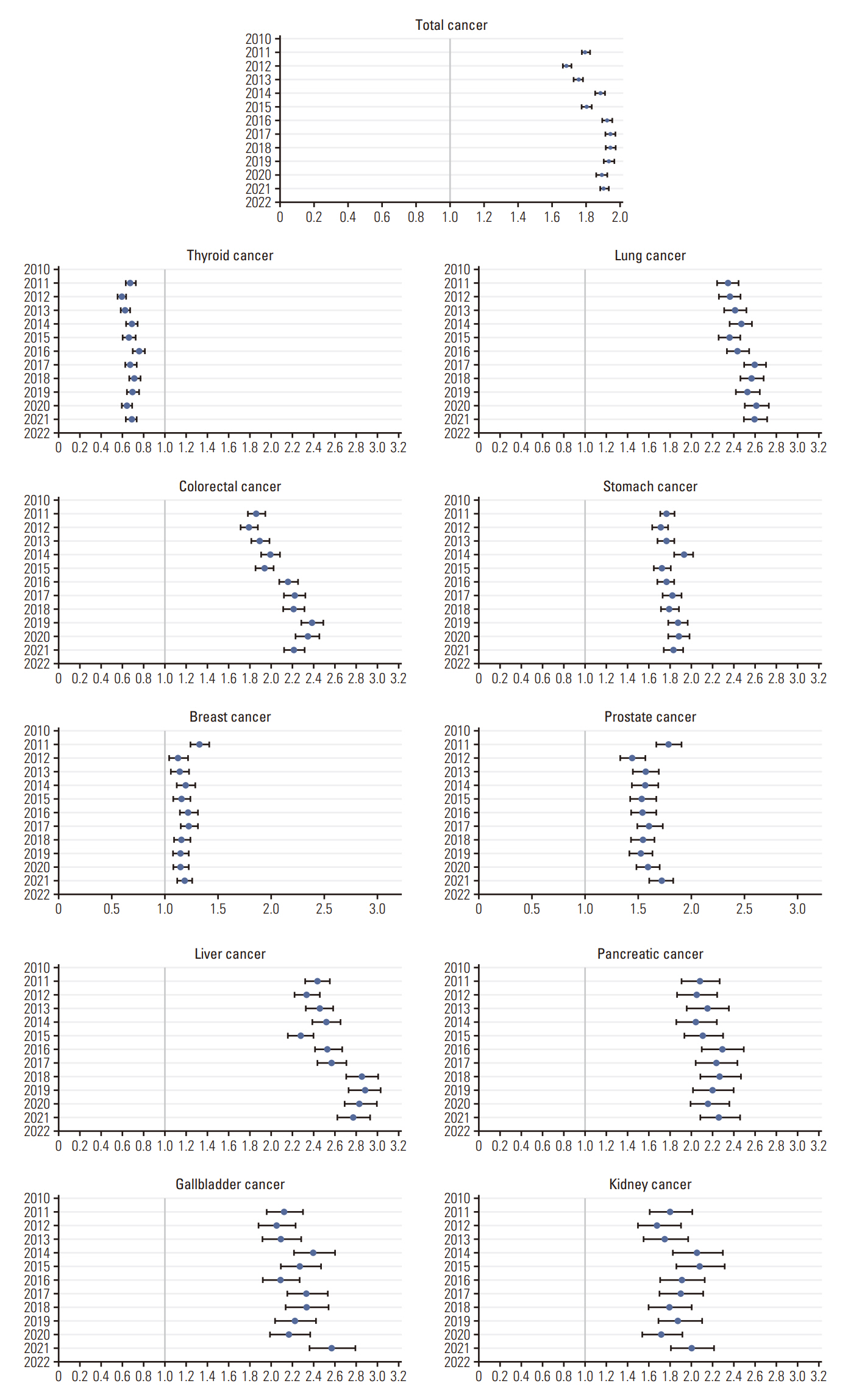

We used the National Health Insurance claims data of the National Health Insurance Service between 2005 and 2022 and annual health insurance and medical aid beneficiaries between 2011 and 2021 to investigate the disparities of cancer incidence. We calculated age-sex standardized cancer incidence rates by cancer and year according to the type of insurance and the trend over time using the annual percentage change. We also compared the hospital type of the first diagnosis by cancer type and year and cancer incidence rates by cancer type and region in 2021 according to the type of insurance.

Results

The total cancer incidence increased from 255,971 in 2011 to 325,772 cases in 2021. The absolute difference of total cancer incidence rate between the NHI beneficiaries and the medical aid (MA) recipients increased from 510.1 cases per 100,000 population to 536.9 cases per 100,000 population. The odds ratio of total cancer incidence for the MA recipients increased from 1.79 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.77 to 1.82) to 1.90 (95% CI, 1.88 to 1.93). Disparities in access to hospitals and regional cancer incidence were profound.

Conclusion

This study examined health inequities in relation to cancer incidence over the last decade. Cancer incidence was higher in the MA recipients, and the gap was widening. We also found that regional differences in cancer incidence still exist and are getting worse. Investigating these disparities between the NHI beneficiaries and the MA recipients is crucial for implementing of public health policies to reduce health inequities.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi-Lakeh M, et al. The global burden of cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 2015; 1:505–27.2. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat. 2019; 51:417–30.

Article3. Ni X, Li Z, Li X, Zhang X, Bai G, Liu Y, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and access to health services among children and adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2022; 400:1020–32.

Article4. Lortet-Tieulent J, Georges D, Bray F, Vaccarella S. Profiling global cancer incidence and mortality by socioeconomic development. Int J Cancer. 2020; 147:3029–36.

Article5. Hajizadeh M, Charles M, Johnston GM, Urquhart R. Socioeconomic inequalities in colorectal cancer incidence in Canada: trends over two decades. Cancer Causes Control. 2022; 33:193–204.

Article6. Derette K, Rollet Q, Launay L, Launoy G, Bryere J; French Network of Cancer Registries (FRANCIM group). Evolution of socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence between 2006 and 2016 in France: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2022; 31:473–81.

Article7. Mihor A, Tomsic S, Zagar T, Lokar K, Zadnik V. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence in Europe: a comprehensive review of population-based epidemiological studies. Radiol Oncol. 2020; 54:1–13.

Article8. Brooke HL, Talback M, Martling A, Feychting M, Ljung R. Socioeconomic position and incidence of colorectal cancer in the Swedish population. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016; 40:188–95.

Article9. Kehm RD, Spector LG, Poynter JN, Vock DM, Osypuk TL. Socioeconomic status and childhood cancer incidence: a population-based multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2018; 187:982–91.

Article10. Cham S, Li A, Rauh-Hain JA, Tergas AI, Hershman DL, Wright JD, et al. Association between neighborhood socioeconomic inequality and cervical cancer incidence rates in New York City. JAMA Oncol. 2022; 8:159–61.

Article11. Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2009; 24:63–71.

Article12. Lee H, Lee JR, Jung H, Lee JY. Power of universal health coverage in the era of COVID-19: a nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021; 7:100088.

Article13. Kyoung DS, Kim HS. Understanding and utilizing claim data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and Health Insurance Review & Assessment (HIRA) database for research. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2022; 11:103–10.

Article14. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; National Health Insurance Service. 2021 National Health Insurance Statistical Yearbook. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service and National Health Insurance Service;2023.15. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2019. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2021.16. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014; 384:1529–40.

Article17. Davis TC, Arnold C, Berkel HJ, Nandy I, Jackson RH, Glass J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 1996; 78:1912–20.

Article18. Welch HG, Fisher ES. Income and cancer overdiagnosis: when too much care is harmful. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:2208–9.

Article19. Zagzag J, Kenigsberg A, Patel KN, Heller KS, Ogilvie JB. Thyroid cancer is more likely to be detected incidentally on imaging in private hospital patients. J Surg Res. 2017; 215:239–44.

Article20. Brodersen J. How to conduct research on overdiagnosis: a keynote paper from the EGPRN May 2016, Tel Aviv. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017; 23:78–82.

Article21. Welch HG, Schwartz L, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed: making people sick in the pursuit of health. Boston, MA: Beacon Press;2011.22. Seo HJ, Oh IH, Yoon SJ. A comparison of the cancer incidence rates between the national cancer registry and insurance claims data in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012; 13:6163–8.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Paradox of the Ugandan Health Insurance System: Challenges and Opportunities for Health Reform

- The fantasy of a new healthcare policy in Korea

- Moving toward Universal Coverage of Health Insurance in Vietnam: Barriers, Facilitating Factors, and Lessons from Korea

- Sustainability of Korean National Health Insurance

- Controversy related to the preliminary coverage system of health insurance