Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2024 Feb;17(1):26-36. 10.21053/ceo.2023.00815.

The Effects of Music-Based Auditory Training on Hearing-Impaired Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Speech Pathology and Audiology, College of Natural Sciences, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea

- 2Laboratory of Hearing and Technology, Research Institute of Audiology and Speech Pathology, College of Natural Sciences, Hallym University, Chuncheon, Korea

- 3Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2553053

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2023.00815

Abstract

Objectives

. The present study aimed to determine the effect of music-based auditory training on older adults with hearing loss and decreased cognitive ability, which are common conditions in the older population.

Methods

. In total, 20 older adults diagnosed with both mild-to-moderately severe hearing loss and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) participated. Half of this group were randomly assigned to the auditory training group (ATG), and the other half were designated as the control group (CG). For the ATG, a 40-minute training session (10 minutes for singing a song, 15 minutes for playing instruments, and 15 minutes for playing games with music discrimination) was conducted twice a week for 8 weeks (for a total of 16 sessions). To confirm the training effects, all participants were given tests pre- and post-training, and then a follow-up test was administered 2 weeks after the training, using various auditory and cognitive tests and a self-reporting questionnaire.

Results

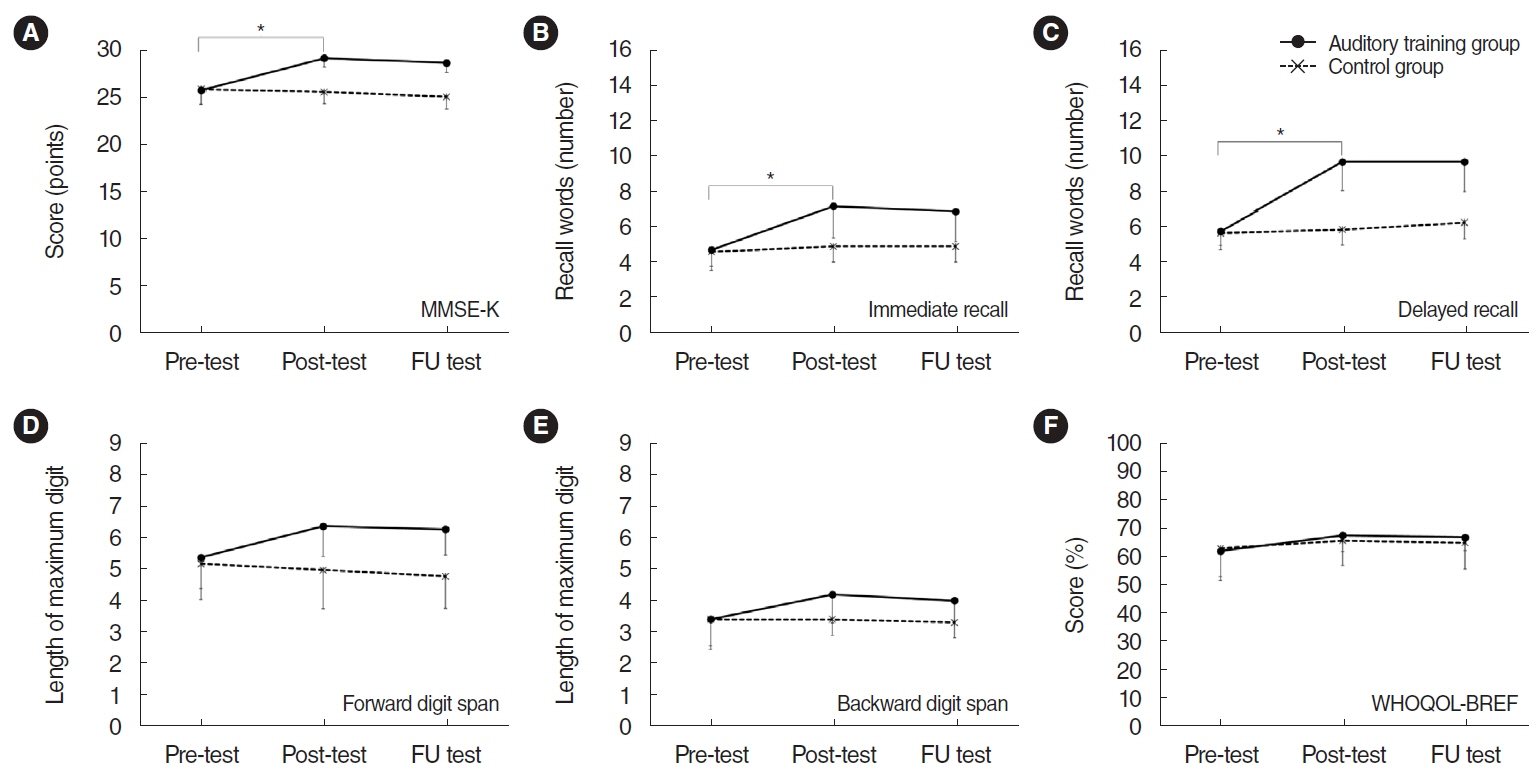

. The ATG demonstrated significant improvement in all auditory test scores compared to the CG. Additionally, there was a notable enhancement in cognitive test scores post-training, except for the digit span tests. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the questionnaire scores between the two groups, although the ATG did score higher post-training.

Conclusion

. The music-based auditory training resulted in a significant improvement in auditory function and a partial enhancement in cognitive ability among elderly patients with hearing loss and MCI. We anticipate that this music-based approach will be adopted for auditory training in clinical settings due to its engaging and easy-to-follow nature.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Dementia [Internet]. World Health Organization;2023. [cited 2023 Dec 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.2. Fetoni AR, Picciotti PM, Paludetti G, Troiani D. Pathogenesis of presbycusis in animal models: a review. Exp Gerontol. 2011; Jun. 46(6):413–25.3. Karr JE, Graham RB, Hofer SM, Muniz-Terrera G. When does cognitive decline begin?: a systematic review of change point studies on accelerated decline in cognitive and neurological outcomes preceding mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and death. Psychol Aging. 2018; Mar. 33(2):195–218.4. Petonito G, Muschert GW. Silver alert: societal aging, dementia, and framing a social problem. In : Wellin C, editor. Critical gerontology comes of age. Routledge;2018. p. 134–50.5. Ford AH, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L, Almeida OP. Hearing loss and the risk of dementia in later life. Maturitas. 2018; Jun. 112:1–11.6. Loughrey DG, Kelly ME, Kelley GA, Brennan S, Lawlor BA. Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018; Feb. 144(2):115–26.7. Wei J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Hao Q, Yang R, Lu H, et al. Hearing impairment, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2017; Dec. 7(3):440–52.8. Hardy CJ, Marshall CR, Golden HL, Clark CN, Mummery CJ, Griffiths TD, et al. Hearing and dementia. J Neurol. 2016; Nov. 263(11):2339–54.9. Park S, Han W, Park KH. Justification for integrated care of dementia and presbycusis: focused on national dementia policy. Audiol Speech Res. 2020; Dec. 17(1):112–9.10. Bottino CM, Carvalho IA, Alvarez AM, Avila R, Zukauskas PR, Bustamante SE, et al. Cognitive rehabilitation combined with drug treatment in Alzheimer’s disease patients: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2005; Dec. 19(8):861–9.11. Brotons M, Koger SM. The impact of music therapy on language functioning in dementia. J Music Ther. 2000; Fall. 37(3):183–95.12. Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia: a multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012; Aug. 27(5):301–10.13. Chu H, Yang CY, Lin Y, Ou KL, Lee TY, O’Brien AP, et al. The impact of group music therapy on depression and cognition in elderly persons with dementia: a randomized controlled study. Biol Res Nurs. 2014; Apr. 16(2):209–17.14. Doi T, Verghese J, Makizako H, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, et al. Effects of cognitive leisure activity on cognition in mild cognitive impairment: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017; Aug. 18(8):686–91.15. Giovagnoli AR, Manfredi V, Parente A, Schifano L, Oliveri S, Avanzini G. Cognitive training in Alzheimer’s disease: a controlled randomized study. Neurol Sci. 2017; Aug. 38(8):1485–93.16. Lyu J, Zhang J, Mu H, Li W, Champ M, Xiong Q, et al. The effects of music therapy on cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018; 64(4):1347–58.17. Tye-Murray N. Foundations of aural rehabilitation: children, adults, and their family members. Plural Publishing;2019.18. McHaney JR, Gnanateja GN, Smayda KE, Zinszer BD, Chandrasekaran B. Cortical tracking of speech in Delta band relates to individual differences in speech in noise comprehension in older adults. Ear Hear. 2021; Mar/Apr. 42(2):343–54.19. Suzuki M, Kanamori M, Watanabe M, Nagasawa S, Kojima E, Ooshiro H, et al. Behavioral and endocrinological evaluation of music therapy for elderly patients with dementia. Nurs Health Sci. 2004; Mar. 6(1):11–8.20. Sarkamo T, Tervaniemi M, Huotilainen M. Music perception and cognition: development, neural basis, and rehabilitative use of music. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2013; Jul. 4(4):441–51.21. Chen JK, Chuang AY, McMahon C, Hsieh JC, Tung TH, Li LP. Music training improves pitch perception in prelingually deafened children with cochlear implants. Pediatrics. 2010; Apr. 125(4):e793–800.22. Janata P, Tillmann B, Bharucha JJ. Listening to polyphonic music recruits domain-general attention and working memory circuits. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2002; Jun. 2(2):121–40.23. Patel AD. Why would musical training benefit the neural encoding of speech?: the OPERA hypothesis. Front Psychol. 2011; Jun. 2:142.24. Patel AD. The OPERA hypothesis: assumptions and clarifications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012; Apr. 1252:124–8.25. Shukor NF, Lee J, Seo YJ, Han W. Efficacy of music training in hearing aid and cochlear implant users: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2021; Feb. 14(1):15–28.26. Corrigall KA, Trainor LJ. Associations between length of music training and reading skills in children. Music Percept. 2011; Dec. 29(2):147–55.27. ISO (International Organization for Standardization). ISO 7029:2017-Acoustics: statistical distribution of hearing thresholds related to age and gender. ISO;2017.28. Kim TH, Jhoo JH, Park JH, Kim JL, Ryu SH, Moon SW, et al. Korean version of mini mental status examination for dementia screening and its’ short form. Psychiatry Investig. 2010; Jun. 7(2):102–8.29. Kang Y, Park J, Yu KH, Lee BC. A reliability, validity, and normative study of the Korean-Montreal Cognitive Assessment (K-MoCA) as an instrument for screening of Vascular Cognitive Impairment (VCI). Korean J Clin Psychol. 2009; 28(2):549–62.30. Song YJ, Lee HJ, Jang HS. A study on the development of Korean National Institute of Special Education-Developmental Assessment of Speech Perception (KNISE-DASP) for auditory training. Spec Educ Res. 2010; 18:3–167.31. Kim KH, Lee JH. Evaluation of the Korean matrix sentence test: verification of the list equivalence and the effect of word position. Audiol Speech Res. 2018; Apr. 14(2):100–7.32. Kim JK, Kang YW. Korean-California Verbal Learning Test (K-CVLT): a normative study. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997; 16(2):379–95.33. Min SK, Lee CI, Kim KI, Suh SY, Kim DK. Development of Korean version of WHO Quality of Life Scale Abbreviated Version (WHOQOL-BREF). J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2000; May. 39(3):571–9.34. Koelsch S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014; Mar. 15(3):170–80.35. Kraus N, Chandrasekaran B. Music training for the development of auditory skills. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010; Aug. 11(8):599–605.36. Jiam NT, Deroche ML, Jiradejvong P, Limb CJ. A randomized controlled crossover study of the impact of online music training on pitch and timbre perception in cochlear implant users. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2019; Jun. 20(3):247–62.37. Zwaan RA. Aspects of literary comprehension: a cognitive approach. John Benjamins Publishing;1993.38. Franklin MS, Sledge Moore K, Yip CY, Jonides J, Rattray K, Moher J. The effects of musical training on verbal memory. Psychol Music. 2008; Jul. 36(3):353–65.39. Parbery-Clark A, Skoe E, Lam C, Kraus N. Musician enhancement for speech-in-noise. Ear Hear. 2009; Dec. 30(6):653–61.40. Cole EB, Flexer C. Children with hearing loss: developing listening and talking, birth to six. Plural Publishing;2019.41. Wayne RV, Johnsrude IS. A review of causal mechanisms underlying the link between age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline. Ageing Res Rev. 2015; Sep. 23(Pt B):154–66.42. Zekveld AA, Kramer SE, Festen JM. Cognitive load during speech perception in noise: the influence of age, hearing loss, and cognition on the pupil response. Ear Hear. 2011; Jul-Aug. 32(4):498–510.43. Baldwin CL. Cognitive implications of facilitating echoic persistence. Mem Cognit. 2007; Jun. 35(4):774–80.44. Nadel L. Multiple memory systems: what and why. J Cogn Neurosci. 1992; Summer. 4(3):179–88.45. Oh E, Lee AY. Mild cognitive impairment. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2016; Aug. 34(3):167–75.46. Li HC, Wang HH, Lu CY, Chen TB, Lin YH, Lee I. The effect of music therapy on reducing depression in people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr Nurs. 2019; Sep-Oct. 40(5):510–6.47. Pedersen SK, Andersen PN, Lugo RG, Andreassen M, Sutterlin S. Effects of music on agitation in dementia: a meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2017; May. 8:742.48. Aastveit AH, Martens H. ANOVA interactions interpreted by partial least squares regression. Biometrics. 1986; Dec. 42(4):829–44.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effects of Cognitive-based Interventions of Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Proximity Analysis of Web-Based Auditory Training Programs: Toward Listening and Customized Learning Exercises for Aural Rehabilitation

- Hearing Screening for Older Adults With Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review

- The Effects of Music Therapy on Cognitive Function and Depression in Demented Old Adults

- Efficacy of Music Training in Hearing Aid and Cochlear Implant Users: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis