J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Jan;39(3):e31. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e31.

Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression Among Korean Women: An Analysis Based on the Korean Pregnancy Outcome Study (KPOS)

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, CHA Gangnam Medical Center, CHA University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Myongji Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea

- 3Division of Biostatistics, Department of Biomedical Systems Informatics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gangseo MizMedi Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 7Smart MEC Healthcare R&D Center, CHA Future Medicine Research Institute, CHA Bundang Medical Center, Seongnam, Korea

- 8Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2551178

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e31

Abstract

- Background

Postpartum depression (PPD) can negatively affect infant well-being and child development. Although the frequency and risk factors of PPD symptoms might vary depending on the country and culture, there is limited research on these risk factors among Korean women. This study aimed to elucidate the potential risk factors of PPD throughout pregnancy to help improve PPD screening and prevention in Korean women.

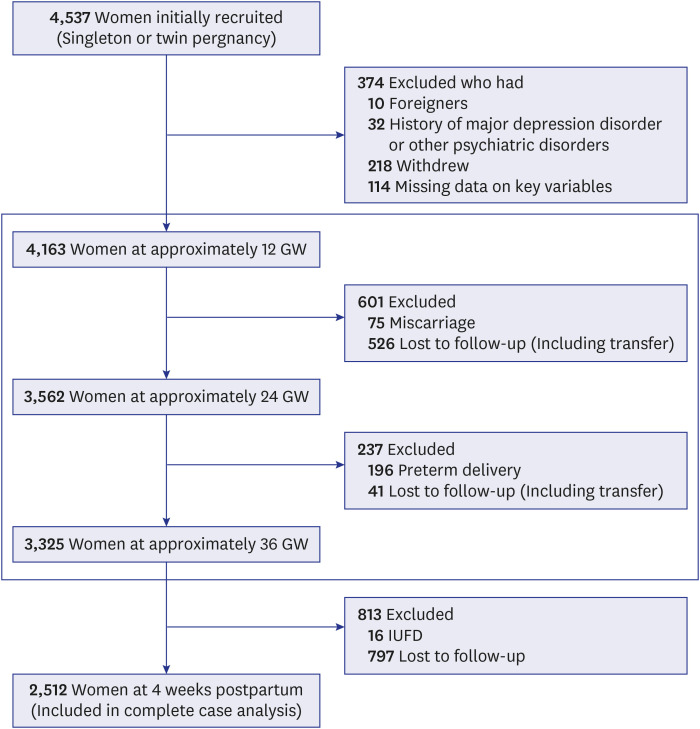

Methods

The pregnant women at 12 gestational weeks (GW) were enrolled from two obstetric specialized hospitals from March 2013 to November 2017. A questionnaire survey was administered at 12 GW, 24 GW, 36 GW, and 4 weeks postpartum. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, and PPD was defined as a score of ≥ 10.

Results

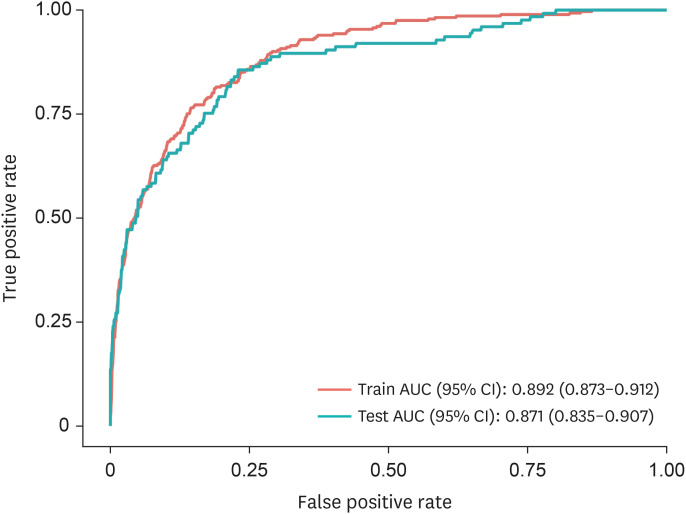

PPD was prevalent in 16.3% (410/2,512) of the participants. Depressive feeling at 12 GW and postpartum factors of stress, relationship with children, depressive feeling, fear, sadness, and neonatal intensive care unit admission of baby were significantly associated with a higher risk of PPD. Meanwhile, high postpartum quality of life and marital satisfaction at postpartum period were significantly associated with a lower risk of PPD. We developed a model for predicting PPD using factors as mentioned above and it had an area under the curve of 0.871.

Conclusion

Depressive feeling at 12 GW and postpartum stress, fear, sadness, relationship with children, low quality of life, and low marital satisfaction increased the risk of PPD. A risk model that comprises significant factors can effectively predict PPD and can be helpful for its prevention and appropriate treatment.

Figure

Reference

-

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing;2013.2. McCurdy AP, Boulé NG, Sivak A, Davenport MH. Effects of exercise on mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms in the postpartum period: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 129(6):1087–1097. PMID: 28486363.3. Yun BS, Shim SH, Cho HY, Heo SJ, Jung I, Jeon HJ, et al. The impacts of insufficient sleep and its change during pregnancy on postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study of Korean women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021; 155(1):125–131. PMID: 33454978.4. Park JH, Karmaus W, Zhang H. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms in Korean women throughout pregnancy and in postpartum period. Asian Nurs Res. 2015; 9(3):219–225.5. Kang SY, Khang YH, June KJ, Cho SH, Lee JY, Kim YM, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of maternal depression among women who participated in a home visitation program in South Korea. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022; 57(6):1167–1178. PMID: 35044478.6. Youn H, Lee S, Han SW, Kim LY, Lee TS, Oh MJ, et al. Obstetric risk factors for depression during the postpartum period in South Korea: a nationwide study. J Psychosom Res. 2017; 102:15–20. PMID: 28992892.7. Choi SK, Ahn SY, Shin JC, Jang DG. A clinical study of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 52(11):1102. 8.8. Kim E, Ryu S. The relationship between depression and sociopsychological factors in pregnant women. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2008; 12(2):228. 41.9. O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013; 9(1):379–407. PMID: 23394227.10. Cho H, Lee K, Choi E, Cho HN, Park B, Suh M, et al. Association between social support and postpartum depression. Sci Rep. 2022; 12(1):3128. PMID: 35210553.11. Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, Rizzo DM, Zoretich RA, Hughes CL, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013; 70(5):490–498. PMID: 23487258.12. Cui C, Li M, Yang Y, Liu C, Cao P, Wang L. The effects of paternal perinatal depression on socioemotional and behavioral development of children: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 284:112775. PMID: 31927302.13. Weitzman M, Rosenthal DG, Liu YH. Paternal depressive symptoms and child behavioral or emotional problems in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011; 128(6):1126–1134. PMID: 22065273.14. Norhayati MN, Hazlina NH, Asrenee AR, Emilin WM. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015; 175:34–52. PMID: 25590764.15. Dagher RK, Shenassa ED. Prenatal health behaviors and postpartum depression: is there an association? Arch Women Ment Health. 2012; 15(1):31–37.16. Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014; 384(9956):1775–1788. PMID: 25455248.17. Stephens S, Ford E, Paudyal P, Smith H. Effectiveness of psychological interventions for postnatal depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2016; 14(5):463–472. PMID: 27621164.18. Choi H, Kwak DW, Kim MH, Lee SY, Chung JH, Han YJ, et al. The Korean Pregnancy Outcome Study (KPOS): study design and participants. J Epidemiol. 2021; 31(6):392–400. PMID: 32595182.19. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150(6):782–786. PMID: 3651732.20. ACOG Committee opinion No. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 132(5):e208–e212. PMID: 30629567.21. Kim YK, Hur JW, Kim KH, Oh KS, Shin YC. Clinical application of Korean version of edinburgh postnatal depression scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2008; 47:36–44.22. Shim EJ, Shin YW, Jeon HJ, Hahm BJ. Distress and its correlates in Korean cancer patients: pilot use of the distress thermometer and the problem list. Psychooncology. 2008; 17(6):548–555. PMID: 17957764.23. Kim MH, Cho YS, Uhm WS, Kim S, Bae SC. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EQ-5D in patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2005; 14(5):1401–1406. PMID: 16047514.24. Logsdon MC, Wisner KL, Pinto-Foltz MD. The impact of postpartum depression on mothering. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006; 35(5):652–658.25. Schaffir J. Consequences of antepartum depression. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 61(3):533–543. PMID: 29659372.26. Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000; 157(6):924–930. PMID: 10831472.27. Okun ML. Disturbed sleep and postpartum depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016; 18(7):66. PMID: 27222140.28. Okun ML, Hanusa BH, Hall M, Wisner KL. Sleep complaints in late pregnancy and the recurrence of postpartum depression. Behav Sleep Med. 2009; 7(2):106–117. PMID: 19330583.29. Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989; 262(11):1479–1484. PMID: 2769898.30. Coll CVN, Domingues MR, Stein A, da Silva BGC, Bassani DG, Hartwig FP, et al. Efficacy of regular exercise during pregnancy on the prevention of postpartum depression: the PAMELA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019; 2(1):e186861. PMID: 30646198.31. Nakamura A, van der Waerden J, Melchior M, Bolze C, El-Khoury F, Pryor L. Physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019; 246:29–41. PMID: 30576955.32. Matsuo S, Ushida T, Iitani Y, Imai K, Nakano-Kobayashi T, Moriyama Y, et al. Pre-pregnancy sleep duration and postpartum depression: a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Women Ment Health. 2022; 25(1):181–189.33. Wolfson AR, Crowley SJ, Anwer U, Bassett JL. Changes in sleep patterns and depressive symptoms in first-time mothers: last trimester to 1-year postpartum. Behav Sleep Med. 2003; 1(1):54–67. PMID: 15600137.34. Wakamatsu M, Nakamura M, Douchi T, Kasugai M, Kodama S, Sano A, et al. Predicting postpartum depression by evaluating temperament during pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2021; 292:720–724. PMID: 34161890.35. Cheng CY, Chou YH, Chang CH, Liou SR. Trends of perinatal stress, anxiety, and depression and their prediction on postpartum depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9307. PMID: 34501906.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms in Korean Women throughout Pregnancy and in Postpartum Period

- Evaluation of Risk Factors for the Postpartum Depression with Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Score

- Domestic Violence Experience, Past Depressive Disorder, Unplanned Pregnancy, and Suicide Risk in the First Year Postpartum: Mediating Effect of Postpartum Depression

- Related Factors to Postpartum Care Performance in Postpartum Women

- Factors influencing prenatal and postpartum depression in Korea: a prospective cohort study