Anesth Pain Med.

2023 Oct;18(4):367-375. 10.17085/apm.23019.

Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion after cesarean delivery for twin pregnancy: a nationwide cohort study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, Wonju, Korea

- 2Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 3Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2550916

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23019

Abstract

- Background

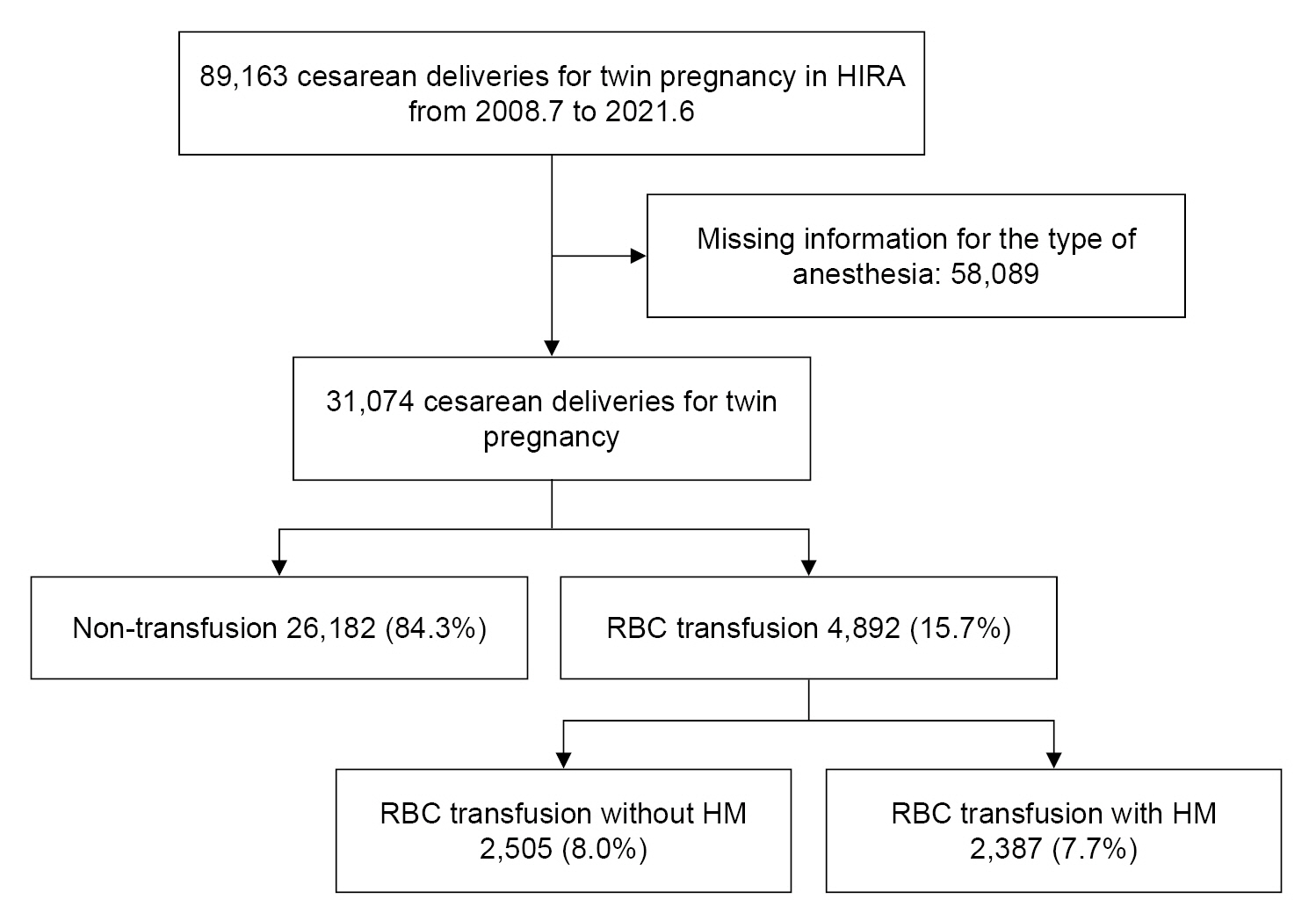

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Twin pregnancy and cesarean delivery are well-known risk factors for PPH. However, few studies have investigated PPH risk factors in mothers who have undergone cesarean delivery for twin pregnancies. Therefore, this study investigated the risk factors associated with severe PPH after cesarean delivery for twin pregnancies. Methods: We searched and reviewed the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service’s claims data from July 2008 to June 2021 using the code corresponding to cesarean delivery for twin pregnancy. Severe PPH was defined as hemorrhage requiring red blood cell (RBC) transfusion during the peripartum period. The risk factors associated with severe PPH were identified among the procedure and diagnosis code variables and analyzed using univariate and multivariate logistic regressions. Results: We analyzed 31,074 cesarean deliveries for twin pregnancies, and 4,892 patients who underwent cesarean deliveries for twin pregnancies and received RBC transfusions for severe PPH were included. According to the multivariate analysis, placental disorders (odds ratio, 4.50; 95% confidence interval, 4.09– 4.95; P < 0.001), general anesthesia (2.33, 2.18–2.49; P < 0.001), preeclampsia (2.20, 1.99–2.43; P < 0.001), hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome (2.12, 1.22–3.68; P = 0.008), induction failure (1.37, 1.07–1.76; P = 0.014), and hypertension (1.31, 1.18–1.44; P < 0.001) predicted severe PPH. Conclusions: Placental disorders, hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome, and induction failure increased the risk of severe PPH after cesarean delivery for twin pregnancy

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, Wapner RJ, Reddy UM, Varner MW, et al. Frequency of and factors associated with severe maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 123:804–10.2. Menard MK, Main EK, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing obstetric data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 124:150–3.3. Butwick AJ, Ramachandran B, Hegde P, Riley ET, El-Sayed YY, Nelson LM. Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean delivery: case-control studies. Anesth Analg. 2017; 125:523–32.

Article4. Ahmadzia HK, Phillips JM, James AH, Rice MM, Amdur RL. Predicting peripartum blood transfusion in women undergoing cesarean delivery: a risk prediction model. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0208417.

Article5. Skjeldestad FE, Oian P. Blood loss after cesarean delivery: a registry-based study in Norway, 1999-2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 206:76. e1-7.

Article6. Blitz MJ, Yukhayev A, Pachtman SL, Reisner J, Moses D, Sison CP, et al. Twin pregnancy and risk of postpartum hemorrhage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020; 33:3740–5.

Article7. Schieve LA. Multiple-gestation pregnancies after assisted reproductive technology treatment: population trends and future directions. Womens Health (Lond). 2007; 3:301–7.

Article8. Suzuki S, Hiraizumi Y, Miyake H. Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage requiring transfusion in cesarean deliveries for Japanese twins: comparison with those for singletons. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012; 286:1363–7.

Article9. Nyfløt LT, Sandven I, Stray-Pedersen B, Pettersen S, Al-Zirqi I, Rosenberg M, et al. Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017; 17:17.

Article10. Lyndon A, Lagrew D, Shields L, Main E, Cape V. Improving health care response to obstetric hemorrhage. Palo Alto, California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative;2015. p. 16–22.11. Jee Y, Lee HJ, Kim YJ, Kim DY, Woo JH. Association between anesthetic method and postpartum hemorrhage in Korea based on National Health Insurance Service data. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2022; 17:165–72.

Article12. Ekin A, Gezer C, Solmaz U, Taner CE, Dogan A, Ozeren M. Predictors of severity in primary postpartum hemorrhage. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015; 292:1247–54.

Article13. Ouh YT, Lee KM, Ahn KH, Hong SC, Oh MJ, Kim HJ, et al. Predicting peripartum blood transfusion: focusing on pre-pregnancy characteristics. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019; 19:477.

Article14. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 130:e168–86.15. Wormer KC, Jamil RT, Bryant SB. Acute postpartum hemorrhage. StatPearls [Internet]. 2022 Oct [cited 2022 Oct 25]. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499988/.16. Parekh N, Husaini SW, Russell IF. Caesarean section for placenta praevia: a retrospective study of anaesthetic management. Br J Anaesth. 2000; 84:725–30.

Article17. Yildiz K, Dogru K, Dalgic H, Serin IS, Sezer Z, Madenoglu H, et al. Inhibitory effects of desflurane and sevoflurane on oxytocin-induced contractions of isolated pregnant human myometrium. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005; 49:1355–9.

Article18. Beilin Y. Maternal hemorrhage-regional versus general anesthesia: does it really matter? Anesth Analg. 2018; 127:805–7.

Article19. Snegovskikh D, Clebone A, Norwitz E. Anesthetic management of patients with placenta accreta and resuscitation strategies for associated massive hemorrhage. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011; 24:274–81.

Article20. Hawkins JL. Excess in moderation: general anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2015; 120:1175–7.21. Eskild A, Vatten LJ. Abnormal bleeding associated with preeclampsia: a population study of 315,085 pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009; 88:154–8.

Article22. Sheiner E, Sarid L, Levy A, Seidman DS, Hallak M. Obstetric risk factors and outcome of pregnancies complicated with early postpartum hemorrhage: a population-based study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005; 18:149–54.

Article23. Saleh L, Verdonk K, Visser W, Van den Meiracker AH, Danser AH. The emerging role of endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2016; 10:282–93.

Article24. Warrington JP, George EM, Palei AC, Spradley FT, Granger JP. Recent advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2013; 62:666–73.

Article25. Grotegut CA, Paglia MJ, Johnson LNC, Thames B, James AH. Oxytocin exposure during labor among women with postpartum hemorrhage secondary to uterine atony. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 204:56.e1-6.

Article26. Rouse DJ, Weiner SJ, Bloom SL, Varner MW, Spong CY, Ramin SM, et al. Failed labor induction: toward an objective diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 117:267–72.

Article27. Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, Dahhou M, Rouleau J, Mehrabadi A, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 209:449.e1-7.

Article28. Liu CN, Yu FB, Xu YZ, Li JS, Guan ZH, Sun MN, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of severe postpartum hemorrhage: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21:332.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- One case of monoamniotic twin pregnancy without cord entanglement and both fetus survival

- Clinical Study on Cesarean Hysterectomy

- Outcomes of ‘one-day trial of vaginal delivery of twins’ at 36–37 weeks' gestation in Japan

- Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome: Diagnosis and Managements

- Acute Sheehan's Syndrome Associated with Postpartum Hemorrhage