Ann Lab Med.

2024 Jan;44(1):38-46. 10.3343/alm.2024.44.1.38.

Changing Genotypic Distribution, Antimicrobial Susceptibilities, and Risk Factors of Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Carbapenemase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Hangang Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2550221

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2024.44.1.38

Abstract

- Background

Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CrPA) is a leading cause of healthcare-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs). Carbapenemase production is an important mechanism that significantly alters the efficacy of frequently used anti-pseudomonal agents. Reporting the current genotypic distribution of carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa (CPPA) isolates in relation to antimicrobial susceptibility, UTI risk factors, and mortality is necessary to increase the awareness and control of these strains.

Methods

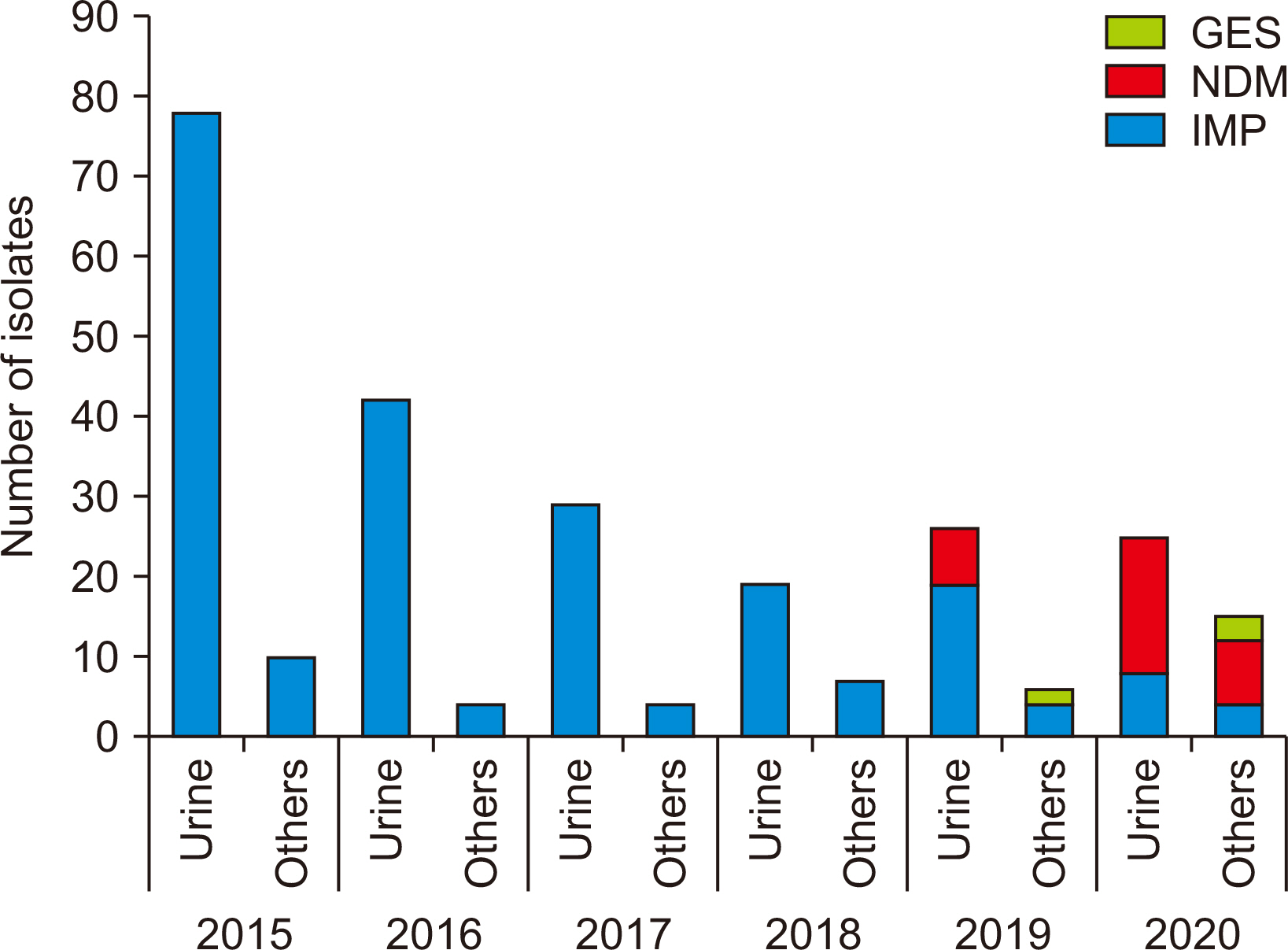

In total, 1,652 non-duplicated P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from hospitalized patients between 2015 and 2020. Antimicrobial susceptibility, carbapenemase genotypes, risk factors for UTI, and associated mortality were analyzed.

Results

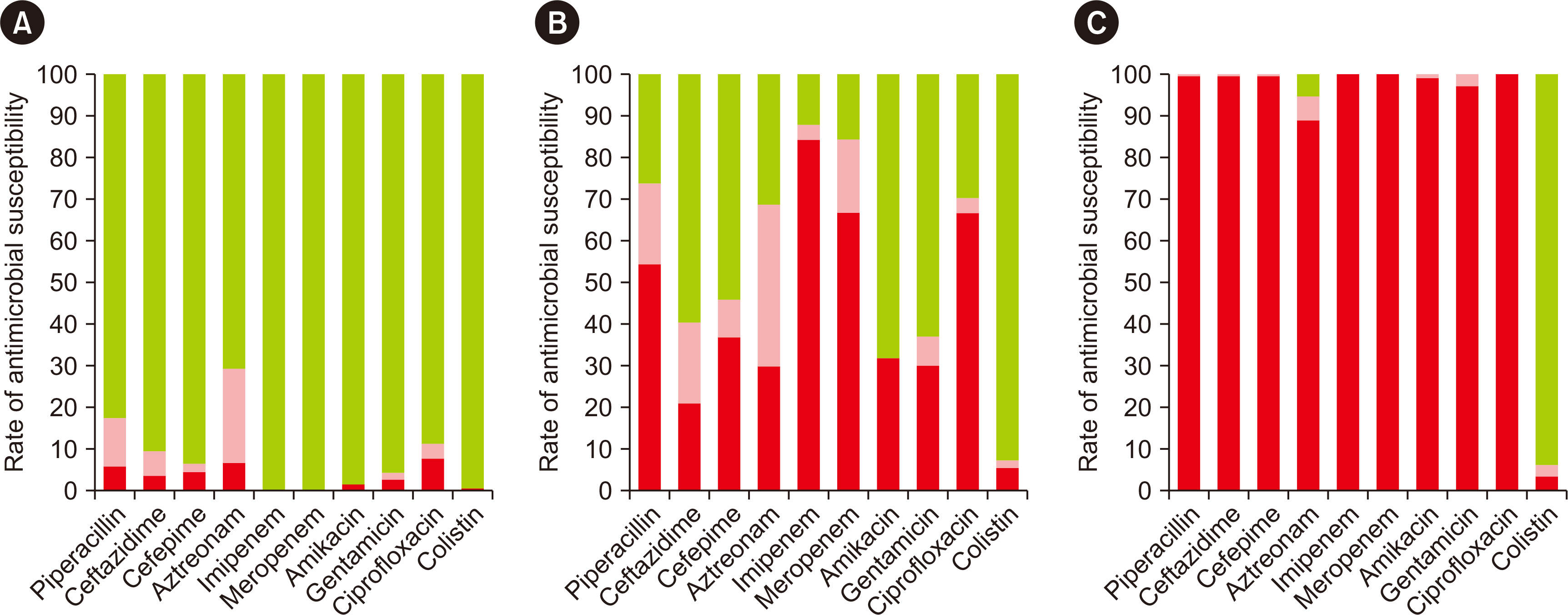

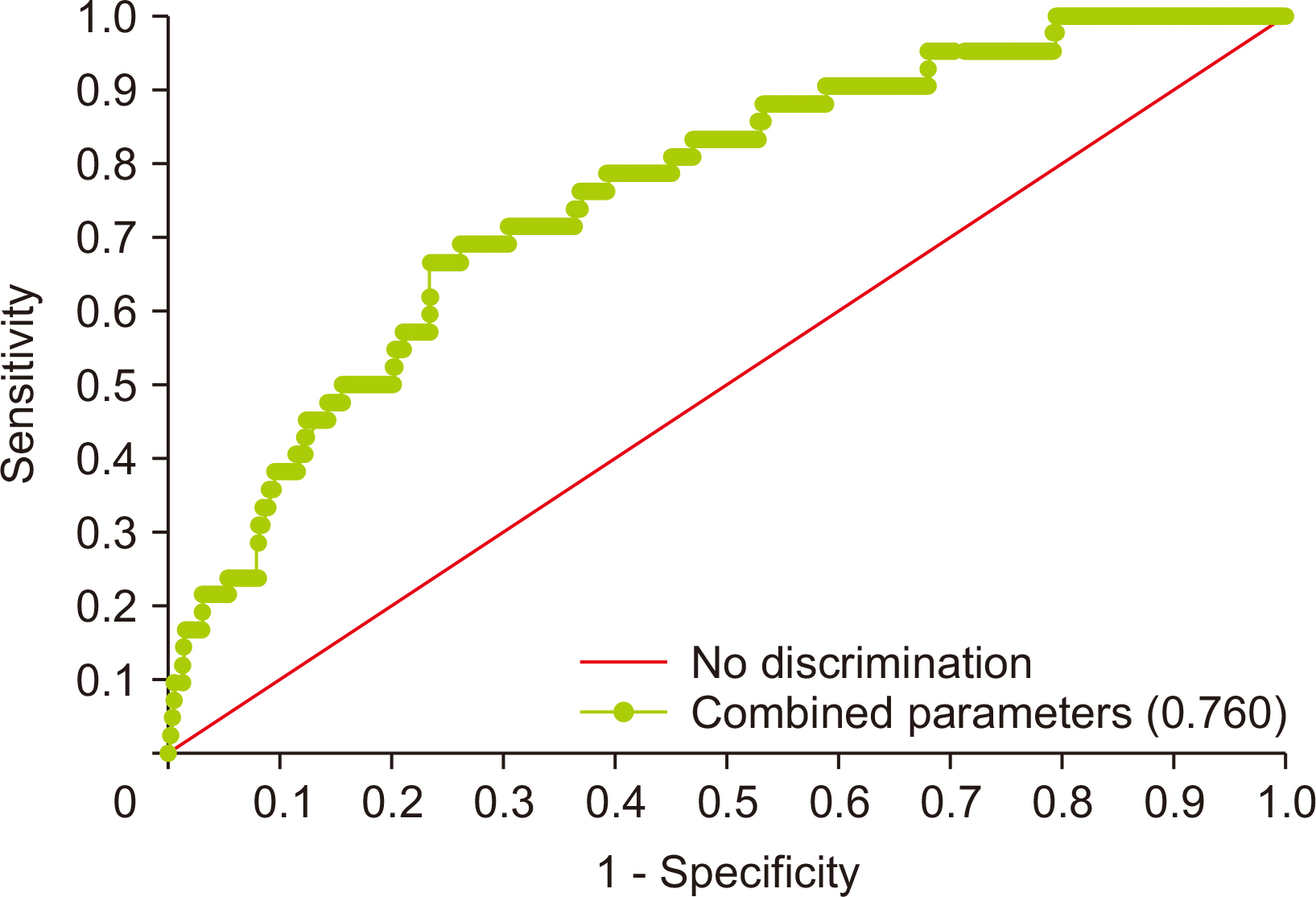

The prevalence of carbapenem-non-susceptible P. aeruginosa isolates showed a decreasing trend from 2015 to 2018 and then increased in the background of the emergence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM)-type isolates since 2019. The CPPA strains showed 100.0% non-susceptibility to all tested antibiotics, except aztreonam (94.5%) and colistin (5.9%). Carbapenems were identified as a risk and common predisposing factor for UTI (odds ratio [OR] = 1.943) and mortality (OR = 2.766). Intensive care unit (ICU) stay (OR = 2.677) and white blood cell (WBC) count (OR = 1.070) were independently associated with mortality.

Conclusions

The changing trend and genetic distribution of CPPA isolates emphasize the need for relentless monitoring to control further dissemination. The use of carbapenems, ICU stay, and WBC count should be considered risk factors, and aggressive antibiotic stewardship programs and monitoring may serve to prevent worse outcomes.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Challenges of Carbapenem-resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Infection Control and Antibiotic Management

Young Jin Kim, Hee Jae Huh, Heungsup Sung

Ann Lab Med. 2024;44(1):1-2. doi: 10.3343/alm.2024.44.1.1.Importance of the Molecular Epidemiological Monitoring of Carbapenem-Resistant

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Young Ah Kim

Ann Lab Med. 2024;44(5):381-382. doi: 10.3343/alm.2024.0184.

Reference

-

1. Weiner-Lastinger LM, Abner S, Edwards JR, Kallen AJ, Karlsson M, Magill SS, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with adult healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2015-2017. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020; 41:1–18. DOI: 10.1017/ice.2019.296. PMID: 31767041. PMCID: PMC8276252.

Article2. Lucena A, Dalla Costa LM, Nogueira KS, Matos AP, Gales AC, Paganini MC, et al. 2014; Nosocomial infections with metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: molecular epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features and outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 87:234–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.05.007. PMID: 25027563.3. Diene SM, Rolain JM. 2014; Carbapenemase genes and genetic platforms in Gram-negative bacilli: Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. Clin Microbiol Infect. 20:831–8. DOI: 10.1111/1469-0691.12655. PMID: 24766097.

Article4. Tenover FC, Nicolau DP, Gill CM. 2022; Carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa -an emerging challenge. Emerg Microbes Infect. 11:811–4. DOI: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2048972. PMID: 35240944. PMCID: PMC8920394.5. Almarzoky Abuhussain SS, Sutherland CA, Nicolau DP. 2019; In vitro potency of antipseudomonal beta-lactams against blood and respiratory isolates of P. aeruginosa collected from US hospitals. J Thorac Dis. 11:1896–902. DOI: 10.21037/jtd.2019.05.13. PMID: 31285882. PMCID: PMC6588753.6. Woodworth KR, Walters MS, Weiner LM, Edwards J, Brown AC, Huang JY, et al. Vital signs: containment of novel multidrug-resistant organisms and resistance mechanisms - United States, 2006-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018; 67:396–401. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6713e1. PMID: 29621209. PMCID: PMC5889247.

Article7. Yong D, Shin HB, Kim YK, Cho J, Lee WG, Ha GY, et al. 2014; Increase in the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter isolates and ampicillin-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella species in Korea: a KONSAR study conducted in 2011. Infect Chemother. 46:84–93. DOI: 10.3947/ic.2014.46.2.84. PMID: 25024870. PMCID: PMC4091365.

Article8. Bae MH, Kim MS, Kim TS, Kim S, Yong D, Ha GY, et al. 2023; Changing epidemiology of pathogenic bacteria over the past 20 years in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 38:e73. DOI: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e73. PMID: 36918027. PMCID: PMC10010907.

Article9. Wang MG, Liu ZY, Liao XP, Sun RY, Li RB, Liu Y, et al. 2021; Retrospective data insight into the global distribution of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics (Basel). 10:548. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics10050548. PMID: 34065054. PMCID: PMC8151531.

Article10. Livermore DM. 2002; Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin Infect Dis. 34:634–40. DOI: 10.1086/338782. PMID: 11823954.11. Yoon EJ, Jeong SH. 2021; Mobile carbapenemase genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol. 12:614058. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.614058. PMID: 33679638. PMCID: PMC7930500.12. Grupper M, Sutherland C, Nicolau DP. 2017; Multicenter evaluation of ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam inhibitory activity against meropenem-nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa from blood, respiratory tract, and wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 61:e00875–17. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00875-17. PMID: 28739780. PMCID: PMC5610483.13. Zavascki AP, Barth AL, Gonçalves AL, Moro AL, Fernandes JF, Martins AF, et al. 2006; The influence of metallo-beta-lactamase production on mortality in nosocomial Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 58:387–92. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkl239. PMID: 16751638.14. Corvec S, Poirel L, Espaze E, Giraudeau C, Drugeon H, Nordmann P. 2008; Long-term evolution of a nosocomial outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing VIM-2 metallo-enzyme. J Hosp Infect. 68:73–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.10.016. PMID: 18079018.

Article15. Kouda S, Ohara M, Onodera M, Fujiue Y, Sasaki M, Kohara T, et al. 2009; Increased prevalence and clonal dissemination of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with the blaIMP-1 gene cassette in Hiroshima. J Antimicrob Chemother. 64:46–51. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkp142. PMID: 19398456.

Article16. CLSI. 2021. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 31st informational supplement. CLSI M100-S31. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;Wayne, PA:17. Jeong S, Lee N, Park MJ, Jeon K, Kim HS, Kim HS, et al. 2022; Genotypic distribution and antimicrobial susceptibilities of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from rectal and clinical samples in Korean university hospitals between 2016 and 2019. Ann Lab Med. 42:36–46. DOI: 10.3343/alm.2022.42.1.36. PMID: 34374347. PMCID: PMC8368229.

Article18. Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. 1988; CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control. 16:128–40. DOI: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. PMID: 2841893.

Article19. Bongiovanni M, Barilaro G, Zanini U, Giuliani G. 2022; Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on multidrug-resistant hospital-acquired bacterial infections. J Hosp Infect. 123:191–2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2022.02.015. PMID: 35245646. PMCID: PMC8885440.

Article20. Jeon K, Jeong S, Lee N, Park MJ, Song W, Kim HS, et al. 2022; Impact of COVID-19 on antimicrobial consumption and spread of multidrug-resistance in bacterial infections. Antibiotics (Basel). 11:535. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics11040535. PMID: 35453286. PMCID: PMC9025690.

Article21. Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Cantón R. COVID-19: impact on prescribing and antimicrobial resistance. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2021; 34(S1):63–8. DOI: 10.37201/req/s01.19.2021. PMID: 34598431. PMCID: PMC8683018.

Article22. O'Toole RF. 2021; The interface between COVID-19 and bacterial healthcare-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 27:1772–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.001. PMID: 34111586. PMCID: PMC8182977.23. Perez LRR, Carniel E, Narvaez GA. 2022; Emergence of NDM-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa among hospitalized patients and impact on antimicrobial therapy during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 43:1279–80. DOI: 10.1017/ice.2021.253. PMID: 34184628.24. Lee K, Lim JB, Yum JH, Yong D, Chong Y, Kim JM, et al. 2002; bla(VIM-2) cassette-containing novel integrons in metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida isolates disseminated in a Korean hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 46:1053–8. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1053-1058.2002. PMID: 11897589. PMCID: PMC127086.

Article25. Seok Y, Bae IK, Jeong SH, Kim SH, Lee H, Lee K. 2011; Dissemination of IMP-6 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequence type 235 in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 66:2791–6. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkr381. PMID: 21933788.26. Park Y, Koo SH. 2022; Epidemiology, molecular characteristics, and virulence factors of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients with urinary tract infections. Infect Drug Resist. 15:141–51. DOI: 10.2147/IDR.S346313. PMID: 35058697. PMCID: PMC8765443.27. Hong JS, Song W, Park MJ, Jeong S, Lee N, Jeong SH. 2021; Molecular characterization of the first emerged NDM-1-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in South Korea. Microb Drug Resist. 27:1063–70. DOI: 10.1089/mdr.2020.0374. PMID: 33332204.28. Khan A, Shropshire WC, Hanson B, Dinh AQ, Wanger A, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. 2020; Simultaneous infection with Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa harboring multiple carbapenemases in a returning traveler colonized with Candida auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 64:e01466–19. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01466-19. PMID: 31658962. PMCID: PMC6985746.29. Perez F, El Chakhtoura NG, Papp-Wallace KM, Wilson BM, Bonomo RA. 2016; Treatment options for infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: can we apply "precision medicine" to antimicrobial chemotherapy? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 17:761–81. DOI: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1145658. PMID: 26799840. PMCID: PMC4970584.30. Marshall S, Hujer AM, Rojas LJ, Papp-Wallace KM, Humphries RM, Spellberg B, et al. 2017; Can ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam overcome β-lactam resistance conferred by metallo-β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 61:e02243–16. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.02243-16. PMID: 28167541. PMCID: PMC5365724.31. Walsh TR, Toleman MA, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2005; Metallo-beta-lactamases: the quiet before the storm? Clin Microbiol Rev. 18:306–25. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.306-325.2005. PMCID: PMC1082798.32. Esposito F, Cardoso B, Fontana H, Fuga B, Cardenas-Arias A, Moura Q, et al. 2021; Genomic analysis of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from urban rivers confirms spread of clone sequence Type 277 carrying broad resistome and virulome beyond the hospital. Front Microbiol. 12:701921. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.701921. PMID: 34539602. PMCID: PMC8446631.33. Mauri C, Maraolo AE, Di Bella S, Luzzaro F, Principe L. 2021; The revival of aztreonam in combination with avibactam against metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negatives: a systematic review of in vitro studies and clinical cases. Antibiotics (Basel). 10:1012. DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics10081012. PMID: 34439062. PMCID: PMC8388901.

Article34. Barron MA, Richardson K, Jeffres M, McCollister B. 2016; Risk factors and influence of carbapenem exposure on the development of carbapenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections and infections at sterile sites. Springerplus. 5:755. DOI: 10.1186/s40064-016-2438-4. PMID: 27386239. PMCID: PMC4912523.35. Tsao LH, Hsin CY, Liu HY, Chuang HC, Chen LY, Lee YJ. 2018; Risk factors for healthcare-associated infection caused by carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 51:359–66. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2017.08.015. PMID: 28988663.36. Lipsitch M, Samore MH. 2002; Antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance: a population perspective. Emerg Infect Dis. 8:347–54. DOI: 10.3201/eid0804.010312. PMID: 11971765. PMCID: PMC2730242.

Article37. Hirakata Y, Yamaguchi T, Nakano M, Izumikawa K, Mine M, Aoki S, et al. 2003; Clinical and bacteriological characteristics of IMP-type metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis. 37:26–32. DOI: 10.1086/375594. PMID: 12830405.

Article38. Shi Q, Huang C, Xiao T, Wu Z, Xiao Y. 2019; A retrospective analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome in carbapenem-susceptible and -non-susceptible infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 8:68. DOI: 10.1186/s13756-019-0520-8. PMID: 31057792. PMCID: PMC6485151.39. Zhang Y, Li Y, Zeng J, Chang Y, Han S, Zhao J, et al. 2020; Risk factors for mortality of inpatients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in China: impact of resistance profile in the mortality. Infect Drug Resist. 13:4115–23. DOI: 10.2147/IDR.S268744. PMID: 33209041. PMCID: PMC7669529.40. George EL, Panos A. 2005; Does a high WBC count signal infection? Nursing. 35:20–1. DOI: 10.1097/00152193-200501000-00014. PMID: 15622174.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Effect of Enoxacin(Flumark) in Urinary Tract Infection - Clinical and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Evaluation-

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Trends and Risk Factors for Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteremia: 12-Year Experience in a Tertiary Hospital in Korea

- Causative Organisms and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Urinary Tract Infection of Spinal Cord Injured Patients

- Mechanisms of ceftolozane/tazobactam resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from South Korea: A diagrostic study

- The Clinical Features of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections by Pseudomonas aeruginosa