J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Dec;38(50):e384. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e384.

Socioeconomic Disparities in the Association Between All-Cause Mortality and Health Check-Up Participation Among Healthy Middle-Aged Workers: A Nationwide Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Public Health, Graduate School, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Global Economics, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea

- 4Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA

- 5The Institute for Occupational Health, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2549954

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e384

Abstract

- Background

This study assessed the relationship between non-participation in health checkups and all-cause mortality and morbidity, considering socioeconomic status.

Methods

Healthy, middle-aged (35–54 years) working individuals who maintained either self-employed or employee status from 2006–2010 were recruited in this retrospective cohort study from the National Health Insurance Service in Korea. Health check-up participation was calculated as the sum of the number of health check-ups in 2007–2008 and 2009–2010. Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of all-cause mortality were estimated for each gender using multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, adjusting for age, income, residential area, and employment status. Interaction of non-participation in health check-ups and employment status on the risk of all-cause mortality was further analyzed.

Results

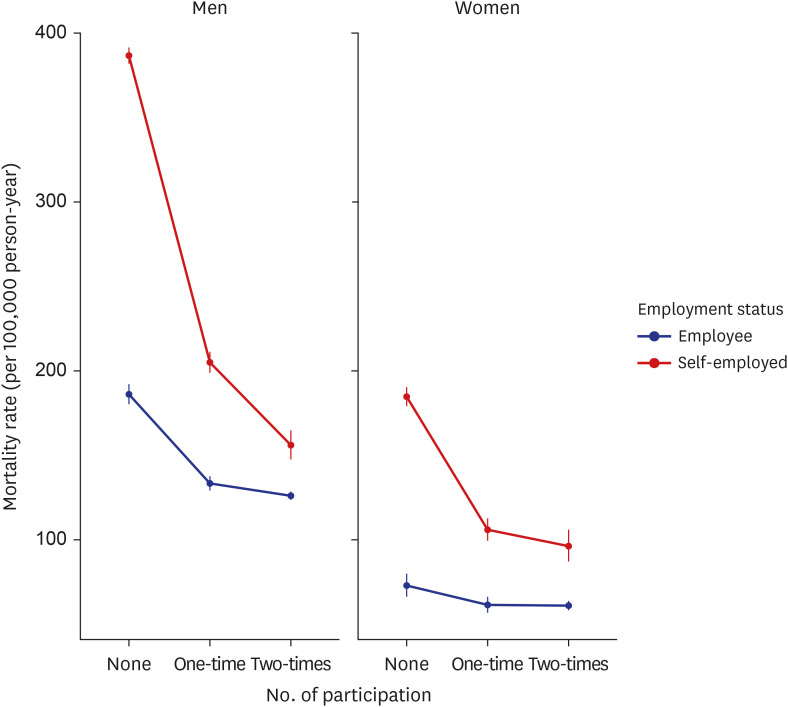

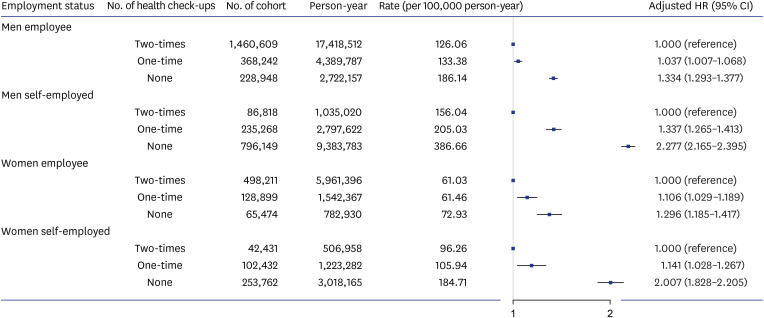

Among 4,267,243 individuals with a median 12-year follow-up (median age, 44; men, 74.43%), 89,030 (2.09%) died. The proportion (number) of deaths of individuals with no, one-time, and two-time participation in health check-ups was 3.53% (n = 47,496), 1.66% (n = 13,835), and 1.33% (n = 27,699), respectively. The association between health checkup participation and all-cause mortality showed a reverse J-shaped curve with the highest adjusted HR (95% CI) of 1.575 (1.541–1.611) and 1.718 (1.628–1.813) for men and women who did not attend any health check-ups, respectively. According to the interaction analysis, both genders showed significant additive and multiplicative interaction, with more pronounced additive interaction among women who did not attend health check-ups (relative excess risk due to interaction, 1.014 [0.871−1.158]).

Conclusion

Our study highlights the significant reverse J-shaped association between health check-up participation and all-cause mortality. A pronounced association was found among self-employed individuals, regardless of gender.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Birtwhistle R, Bell NR, Thombs BD, Grad R, Dickinson JA. Periodic preventive health visits: a more appropriate approach to delivering preventive services: from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Can Fam Physician. 2017; 63(11):824–826. PMID: 29138150.2. Goodyear-Smith F. Government’s plans for universal health checks for people aged 40-75. BMJ. 2013; 347:f4788. PMID: 23900533.3. Goto E, Ishikawa H, Okuhara T, Kiuchi T. Relationship of health literacy with utilization of health-care services in a general Japanese population. Prev Med Rep. 2019; 14:100811. PMID: 30815332.4. Grosios K, Gahan PB, Burbidge J. Overview of healthcare in the UK. EPMA J. 2010; 1(4):529–534. PMID: 23199107.5. Kahl H, Hölling H, Kamtsiuris P. Utilization of health screening studies and measures for health promotion. Gesundheitswesen. 1999; 61:S163–S168. PMID: 10726416.6. Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ, Krogsbøll LT. General health checks don’t work. BMJ. 2014; 348:g3680. PMID: 24912801.7. Si S, Moss JR, Sullivan TR, Newton SS, Stocks NP. Effectiveness of general practice-based health checks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2014; 64(618):e47–e53. PMID: 24567582.8. Seiler N, Malcarney MB, Horton K, Dafflitto S. Coverage of clinical preventive services under the Affordable Care Act: from law to access. Public Health Rep. 2014; 129(6):526–532. PMID: 25364055.9. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Framework Act on Health Examination. Chapter 1 General Provisions . Sejong, Korea: Korea Legislation Research Institute;2018.10. Shin DW, Cho J, Park JH, Cho BJP, Medicine F. National General Health Screening Program in Korea: history, current status, and future direction: a scoping review. Precis Future Med. 2022; 6(1):9–31.11. OECD. OECD Factbook 2008: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics . Paris, France: OECD;2008.12. Kim S, Song JH, Oh YM, Park SM. Disparities in the utilisation of preventive health services by the employment status: an analysis of 2007–2012 South Korean national survey. PLoS One. 2018; 13(12):e0207737. PMID: 30586360.13. Hakro S, Jinshan L. Workplace employees’ annual physical checkup and during hire on the job to increase health-care awareness perception to prevent disease risk: a work for policy-implementable option globally. Saf Health Work. 2019; 10(2):132–140. PMID: 31297275.14. Ha R, Jung-Choi K, Kim CY. Employment status and self-reported unmet healthcare needs among South Korean employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019; 16(1):9.15. Lee H, Cho J, Shin DW, Lee SP, Hwang SS, Oh J, et al. Association of cardiovascular health screening with mortality, clinical outcomes, and health care cost: a nationwide cohort study. Prev Med. 2015; 70:19–25. PMID: 25445334.16. Suh Y, Lee CJ, Cho DK, Cho YH, Shin DH, Ahn CM, et al. Impact of national health checkup service on hard atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events and all-cause mortality in the general population. Am J Cardiol. 2017; 120(10):1804–1812. PMID: 28886857.17. Kim HK, Song SO, Noh J, Jeong IK, Lee BW. Data configuration and publication trends for the Korean National Health Insurance and Health Insurance Review & Assessment database. Diabetes Metab J. 2020; 44(5):671–678. PMID: 33115211.18. Lee C, Sung NJ, Lim HS, Lee JH. Emergency department visits can be reduced by having a regular doctor for adults with diabetes mellitus: secondary analysis of 2013 Korea health panel data. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(12):1921–1930. PMID: 29115072.19. Sung NJ, Choi YJ, Lee JH. Primary care comprehensiveness can reduce emergency department visits and hospitalization in people with hypertension in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018; 15(2):272. PMID: 29401740.20. Lee DH, Kim SY, Park JE, Jeon HJ, Park JH, Kawachi I. Nationwide trends in prevalence of underweight, overweight, and obesity among people with disabilities in South Korea from 2008 to 2017. Int J Obes (Lond). 2022; 46(3):613–622. PMID: 34862471.21. Shin DW, Cho J, Park JH, Cho B. National General Health Screening Program in Korea: history, current status, and future direction. Precision and Future Medicine. 2022; 6(1):9–31.22. Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ, Groenwold RH, Klungel OH, Rovers MM, Grobbee DE. Estimating measures of interaction on an additive scale for preventive exposures. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011; 26(6):433–438. PMID: 21344323.23. Richardson DB, Kaufman JS. Estimation of the relative excess risk due to interaction and associated confidence bounds. Am J Epidemiol. 2009; 169(6):756–760. PMID: 19211620.24. Li R, Chambless L. Test for additive interaction in proportional hazards models. Ann Epidemiol. 2007; 17(3):227–236. PMID: 17320789.25. Song SO, Jung CH, Song YD, Park CY, Kwon HS, Cha BS, et al. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean national health insurance system. Diabetes Metab J. 2014; 38(5):395–403. PMID: 25349827.26. Shin HY, Kang HT, Lee JW, Lim HJ. The association between socioeconomic status and adherence to health check-up in Korean adults, based on the 2010–2012 Korean national health and nutrition examination survey. Korean J Fam Med. 2018; 39(2):114–121. PMID: 29629044.27. Dunlop S, Coyte PC, McIsaac W. Socio-economic status and the utilisation of physicians’ services: results from the Canadian national population health survey. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 51(1):123–133. PMID: 10817475.28. Lee YY, Jun JK, Suh M, Park BY, Kim Y, Choi KS. Barriers to cancer screening among medical aid program recipients in the Republic of Korea: a qualitative study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014; 15(2):589–594. PMID: 24568462.29. Article 175 Administrative Fines, Occupational Safety and Health Act, Employment and Labor . Sejong, Korea: Korea Legislation Research Institute;2020.30. Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, Brunner E, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA. 2010; 303(12):1159–1166. PMID: 20332401.31. Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, Avendaño M, Muennig P, Guida F, et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet. 2017; 389(10075):1229–1237. PMID: 28159391.32. Park BH, Lee BK, Ahn J, Kim NS, Park J, Kim Y. Association of participation in health check-ups with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(3):e19. PMID: 33463093.33. Rakowski W, Clark MA, Ehrich B. Smoking and cancer screening for women ages 42-75: associations in the 1990–1994 national health interview surveys. Prev Med. 1999; 29(6 Pt 1):487–495. PMID: 10600429.34. Short SE, Mollborn S. Social determinants and health behaviors: conceptual frames and empirical advances. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015; 5:78–84. PMID: 26213711.35. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Updated 2023. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople .36. Odegaard AO, Koh WP, Gross MD, Yuan JM, Pereira MA. Combined lifestyle factors and cardiovascular disease mortality in Chinese men and women: the Singapore Chinese health study. Circulation. 2011; 124(25):2847–2854. PMID: 22104554.37. Zhang YB, Pan XF, Chen J, Cao A, Xia L, Zhang Y, et al. Combined lifestyle factors, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021; 75(1):92–99. PMID: 32892156.38. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, Vancampfort D, Schuch FB, Hoare E, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020; 19(3):360–380. PMID: 32931092.39. Cho HW, Song IA, Oh TK. Quality of life and long-term mortality among survivors of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a nationwide cohort study in South Korea. Crit Care Med. 2021; 49(8):e771–e780. PMID: 34261933.40. Park JH, Park JH, Kim SG. Effect of cancer diagnosis on patient employment status: a nationwide longitudinal study in Korea. Psychooncology. 2009; 18(7):691–699. PMID: 19021127.41. Jeong S, Cho SI, Kong SY. Long-term effect of income level on mortality after stroke: a nationwide cohort study in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8348. PMID: 33187353.42. Kang YJ, Lee DW, Park MY, Kang MY. Employment status transition predicts adult obesity trajectory: evidence from a cohort study in South Korea. J Occup Environ Med. 2021; 63(12):e861–e867. PMID: 34538837.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Socioeconomic Disparities in Breast Cancer Screening among US Women: Trends from 2000 to 2005

- The Perceived Socioeconomic Status Is an Important Factor of Health Recovery for Victims of Occupational Accidents in Korea

- Trend of Socioeconomic Inequality in Participation in Cervical Cancer Screening among Korean Women

- Effects of Working Environment and Socioeconomic Status on Health Status in Elderly Workers: A Comparison with Non-Elderly Workers

- Study on the workers' participation in industries