J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Dec;38(49):e372. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e372.

Nationwide Long-Term Growth and Developmental Outcomes of Infants for Congenital Anomalies in the Digestive System and Abdominal Wall Defects With Surgery in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Seoul National University-Seoul Metropolitan Government Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 5Department of Pediatrics, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Pediatrics, Konyang University College of Medicine, Daejeon, Korea

- 7Department of Pediatrics, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Pediatrics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 9Department of Health Sciences and Technology, Samsung Advanced Institute for Health Sciences & Technology (SAIHST), Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2549172

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e372

Abstract

- Background

Infants with congenital anomalies of the digestive system and abdominal wall defects requiring surgery are at risk of growth and developmental delays. The aim of this study was to analyze long-term growth and developmental outcomes for infants with congenital anomalies of the digestive system and abdominal wall defects who underwent surgery in Korea.

Methods

We extracted data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service database for the years 2013–2019. Major congenital anomalies were defined according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 and surgery insurance claim codes. The χ 2 test and the CochranArmitage trend test were performed for data analysis.

Results

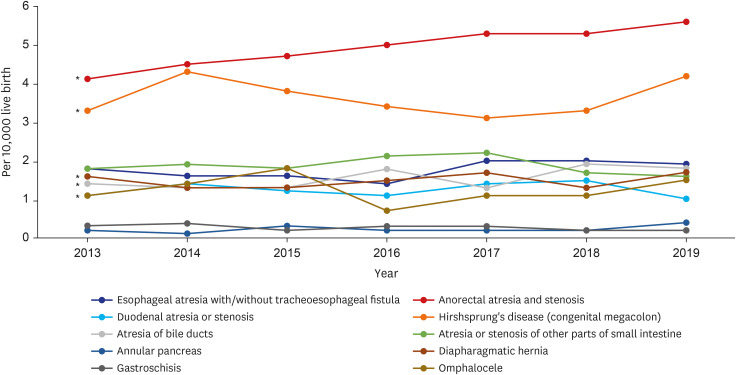

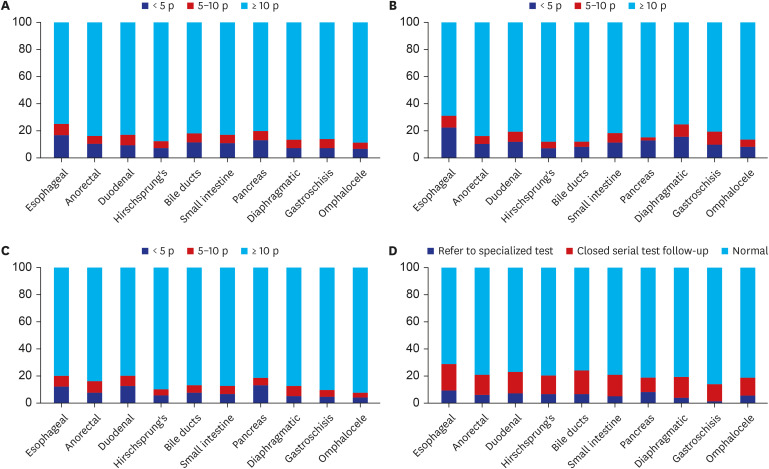

A total of 4,574 infants with major congenital anomalies in the digestive system and abodminal wall defects, who had undergone surgey, were reviewed. Anorectal obstruction/ stenosis was the most prevalent anomaly (4.9 per 10,000 live births). The prevalence of congenital anomalies of the digestive system was 15.5 per 10,000 live births, and that of abdominal wall defects was 1.5 per 10,000 live births. Seven percent of infants with congenital anomalies in the digestive system died, of which those with diaphragmatic hernia had the highest mortality rate (18.8%). Among 12,336 examinations at 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 months of age, 16.7% showed a weight below the 10th percentile, 15.8% had a height below the 10th percentile, and 13.2% had a head circumference below the 10th percentile. Abnormal developmental screening results were observed in 23.0% of infants. Infants with esophageal atresia with/without tracheoesophageal fistula most often had poor growth and development. Delayed development and cerebral palsy were observed in 490 (10.7%) and 130 (2.8%) infants respectively. Comparing the results of infants born in 2013 between their 24- and 72-month health examinations, the proportions of infants with poor height and head circumference growth increased by 6.5% and 5.3%, respectively, whereas those with poor weight growth and abnormal developmental results did not markedly change between the two examinations.

Conclusion

Infants with congenital anomalies of the digestive system and abdominal wall defects exhibit poor growth and developmental outcomes until 72 months of age. Close monitoring and careful consideration of their growth and development after discharge are required.

Figure

Reference

-

1. World Health Organization. Global health estimates: life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability. Updated 2016. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html .2. Mao L, Shen Y, Wu J. Short bowel syndrome in neonates: a review. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2017; 22:29–34.3. Council on Communications and Media. Policy statement—media violence. Pediatrics. 2009; 124(5):1495–1503. PMID: 19841118.4. Eitan Kerem AF, Ledder O. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow milk allergy: is there a correlation? J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45(8):1599–1603.5. Chung SH, Kim CY, Lee BS. Korean Neonatal Network. Congenital anomalies in very-low-birth-weight infants: a nationwide cohort study. Neonatology. 2020; 117(5):584–591. PMID: 32772029.6. Boyle B, Addor MC, Arriola L, Barisic I, Bianchi F, Csáky-Szunyogh M, et al. Estimating Global Burden of Disease due to congenital anomaly: an analysis of European data. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018; 103(1):F22–F28. PMID: 28667189.7. Morris PJ, Wood WC. Chapter 29: congenital abnormalities of the abdominal wall. Oxford Textbook of Surgery. 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press;2000.8. European Commission. Prevalence charts and tables. Updated 2022. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/eurocat/eurocat-data/prevalence_en .9. Feldkamp ML, Carey JC, Sadler TW. Development of gastroschisis: review of hypotheses, a novel hypothesis, and implications for research. Am J Med Genet A. 2007; 143A(7):639–652. PMID: 17230493.10. Moldenhauer JS. Gastroschisis and omphalocele. Gleason CA, Juul SE, editors. Avery’s Diseases of the Newborn. 10th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier;2018. p. 1063–1070.11. Optum. ICD-10-CM. The Complete Official Draft Code Set 2015. Salt Lake City, UT, USA: Optum;2014.12. Korean Statistical Information Service. Birth statistics. Updated 2022. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsListIndex.do?vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&menuId=M_01_01#content-group .13. National Health Insurance Service (KR). Infants and children health checkup guide. Updated 2021. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.nhis.or.kr/nhis/healthin/wbhaca04800m01.do .14. Eun BL. Standardization and Validity Reevaluation of the Korean Developmental Screening Test for Infants & Children. Cheongju, Korea: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2017.15. Dusick AM, Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA, Lemons JA. Growth failure in the preterm infant: can we catch up? Semin Perinatol. 2003; 27(4):302–310. PMID: 14510321.16. Shin M, Kucik JE, Siffel C, Lu C, Shaw GM, Canfield MA, et al. Improved survival among children with spina bifida in the United States. J Pediatr. 2012; 161(6):1132–1137. PMID: 22727874.17. World Health Organization. Global Burden of Disease. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2008.18. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Congenital anomalies in Australia. Updated 2022. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/congenital-anomalies-in-australia-2016/contents/congenital-anomalies-in-australia .19. Global PaedSurg Research Collaboration. Mortality from gastrointestinal congenital anomalies at 264 hospitals in 74 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a multicentre, international, prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021; 398(10297):325–329. PMID: 34270932.20. Haga NHT, Ohashi K, Hoshina T, Kato T, Okuyama H. Catch-up growth of neonates with congenital gastrointestinal anomalies. Pediatr Int. 2020; 62(5):534–539.21. Leeuwen L, Walker K, Halliday R, Karpelowsky J, Fitzgerald DA. Growth in children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia during the first year of life. J Pediatr Surg. 2014; 49(9):1363–1366. PMID: 25148738.22. Roorda D, Königs M, Eeftinck Schattenkerk L, van der Steeg L, van Heurn E, Oosterlaan J. Neurodevelopmental outcome of patients with congenital gastrointestinal malformations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021; 106(6):635–642. PMID: 34112720.23. Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Wiedemann A, Ratkiewicz A, Bucher HU, Arlettaz R, Adams M, et al. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and gastroschisis. Eur J Pediatr. 2020; 170(10):1607–1616.24. Yoon SW, Jin JH, Chung HJ, Song J, Lee SA. Improvement of Support Policy through Clinical Prognosis by Gestational age of Premature Infants. Goyang, Korea: National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital;2020.25. Oh C, Lee S, Chang HK, Ahn SM, Chae K, Kim S, et al. Analysis of pediatric surgery using the National Healthcare Insurance Service Database in Korea: how many pediatric surgeons do we need in Korea? J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(18):e116. PMID: 33975393.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Comparative Study on the Growth alpha Developmental Status of Premature and Full Term Infants During the First 3Years

- Clinical Features and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Infants with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Single NICU Experience

- A Case of Congenital Craniofacial Anomaly due to Amniotic Band Syndrome

- Long Term Developmental Outcomes of Patients with Congenital Heart Disease

- Management of the Sequelae of Severe Congenital Abdominal Wall Defects