Korean J Orthod.

2023 Nov;53(6):345-357. 10.4041/kjod23.184.

Managing oral biofilms to avoid enamel demineralization during fixed orthodontic treatment

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, Dental Research Institute, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Dental Biomaterials, School of Dentistry, Dental Research Institute, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2548479

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4041/kjod23.184

Abstract

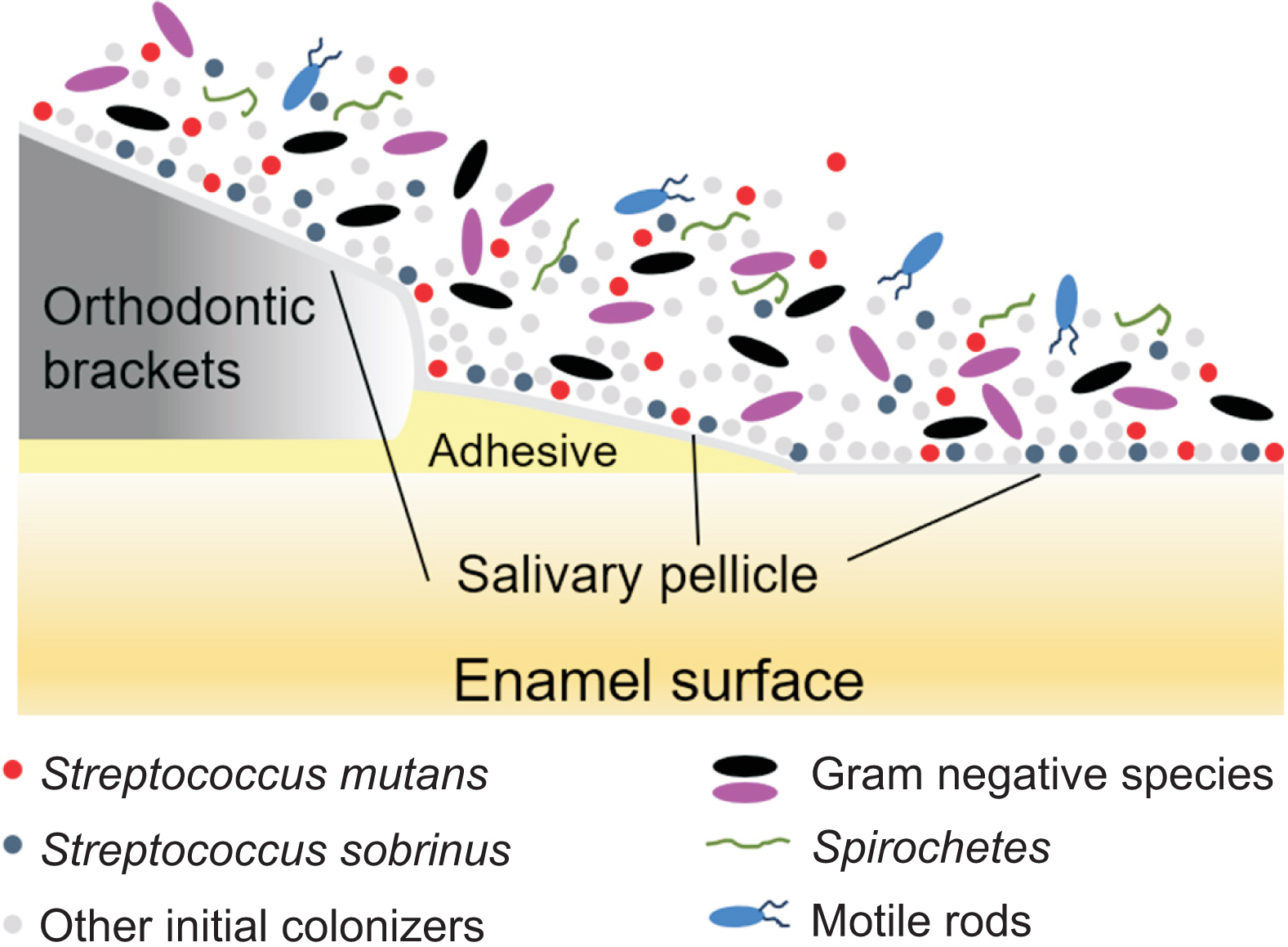

- Enamel demineralization represents the most prevalent complication arising from fixed orthodontic treatment. Its main etiology is the development of cariogenic biofilms formed around orthodontic appliances. Ordinarily, oral biofilms exist in a dynamic equilibrium with the host's defense mechanisms. However, the equilibrium can be disrupted by environmental changes, such as the introduction of a fixed orthodontic appliance, resulting in a shift in the biofilm’s microbial composition from non-pathogenic to pathogenic. This alteration leads to an increased prevalence of cariogenic bacteria, notably mutans streptococci, within the biofilm. This article examines the relationships between oral biofilms and orthodontic appliances, with a particular focus on strategies for effectively managing oral biofilms to mitigate enamel demineralization around orthodontic appliances.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Mizrahi E. 1982; Enamel demineralization following orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod. 82:62–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9416(82)90548-6. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90548-6. PMID: 6984291.

Article2. Lucchese A, Gherlone E. 2013; Prevalence of white-spot lesions before and during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 35:664–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjs070. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cjs070. PMID: 23045306.

Article3. Sharab L, Loss C, Jensen D, Kluemper GT, Alotaibi M, Nagaoka H. 2023; Prevalence of white spot lesions and gingival index during orthodontic treatment in an academic setting. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 163:835–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.08.023. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.08.023. PMID: 36720655.

Article4. Sonesson M, Bergstrand F, Gizani S, Twetman S. 2017; Management of post-orthodontic white spot lesions: an updated systematic review. Eur J Orthod. 39:116–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjw023. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cjw023. PMID: 27030284.

Article5. Ulukapi H, Koray F, Efes B. 1997; Monitoring the caries risk of orthodontic patients. Quintessence Int. 28:27–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10332351/. PMID: 10332351.6. Babaahmady KG, Challacombe SJ, Marsh PD, Newman HN. 1998; Ecological study of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus and Lactobacillus spp. at sub-sites from approximal dental plaque from children. Caries Res. 32:51–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000016430. DOI: 10.1159/000016430. PMID: 9438572.7. Ahn SJ, Lim BS, Yang HC, Chang YI. 2005; Quantitative analysis of the adhesion of cariogenic streptococci to orthodontic metal brackets. Angle Orthod. 75:666–71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16097239/. DOI: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[666:QAOTAO]2.0.CO;2. PMID: 16097239.8. Ahn SJ, Lim BS, Lee YK, Nahm DS. 2006; Quantitative determination of adhesion patterns of cariogenic streptococci to various orthodontic adhesives. Angle Orthod. 76:869–75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17029524/. DOI: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0869:QDOAPO]2.0.CO;2. PMID: 17029524.9. Ahn SJ, Lee SJ, Lim BS, Nahm DS. 2007; Quantitative determination of adhesion patterns of cariogenic streptococci to various orthodontic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 132:815–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.034. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.09.034. PMID: 18068602.

Article10. Lim BS, Lee SJ, Lee JW, Ahn SJ. 2008; Quantitative analysis of adhesion of cariogenic streptococci to orthodontic raw materials. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 133:882–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.07.027. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.07.027. PMID: 18538253.

Article11. Lee SP, Lee SJ, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2009; Surface characteristics of orthodontic materials and their effects on adhesion of mutans streptococci. Angle Orthod. 79:353–60. https://doi.org/10.2319/021308-88.1. DOI: 10.2319/021308-88.1. PMID: 19216592.

Article12. Ahn SJ, Lim BS, Lee SJ. 2010; Surface characteristics of orthodontic adhesives and effects on streptococcal adhesion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 137:489–95. discussion 13Ahttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.05.015. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.05.015. PMID: 20362908.

Article13. Ahn SJ, Cho EJ, Oh SS, Lim BS. 2012; The effects of orthodontic bonding steps on biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans in the presence of saliva. Acta Odontol Scand. 70:504–10. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016357.2011.640277. DOI: 10.3109/00016357.2011.640277. PMID: 22181697.

Article14. Park JW, Song CW, Jung JH, Ahn SJ, Ferracane JL. 2012; The effects of surface roughness of composite resin on biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans in the presence of saliva. Oper Dent. 37:532–9. https://doi.org/10.2341/11-371-L. DOI: 10.2341/11-371-L. PMID: 22339385.

Article15. Jung WS, Kim H, Park SY, Cho EJ, Ahn SJ. 2014; Quantitative analysis of changes in salivary mutans streptococci after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 145:603–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.12.025. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.12.025. PMID: 24785924.

Article16. Jung WS, Yang IH, Lim WH, Baek SH, Kim TW, Ahn SJ. 2015; Adhesion of mutans streptococci to self-ligating ceramic brackets: in vivo quantitative analysis with real-time polymerase chain reaction. Eur J Orthod. 37:565–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cju090. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cju090. PMID: 25564502.

Article17. An JS, Kim K, Cho S, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2017; Compositional differences in multi-species biofilms formed on various orthodontic adhesives. Eur J Orthod. 39:528–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjw089. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/cjw089. PMID: 28339597.

Article18. Jeon DM, An JS, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2020; Orthodontic bonding procedures significantly influence biofilm composition. Prog Orthod. 21:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-020-00314-8. DOI: 10.1186/s40510-020-00314-8. PMID: 32476070. PMCID: PMC7261716. PMID: 8beaedc11b354e41ac8187cdefaefb8f.

Article19. Park SH, Kim K, Cho S, Chung DH, Ahn SJ. 2022; Variation in adhesion of Streptococcus mutans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in saliva-derived biofilms on raw materials of orthodontic brackets. Korean J Orthod. 52:278–86. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod21.283. DOI: 10.4041/kjod21.283. PMID: 35678009. PMCID: PMC9314218.

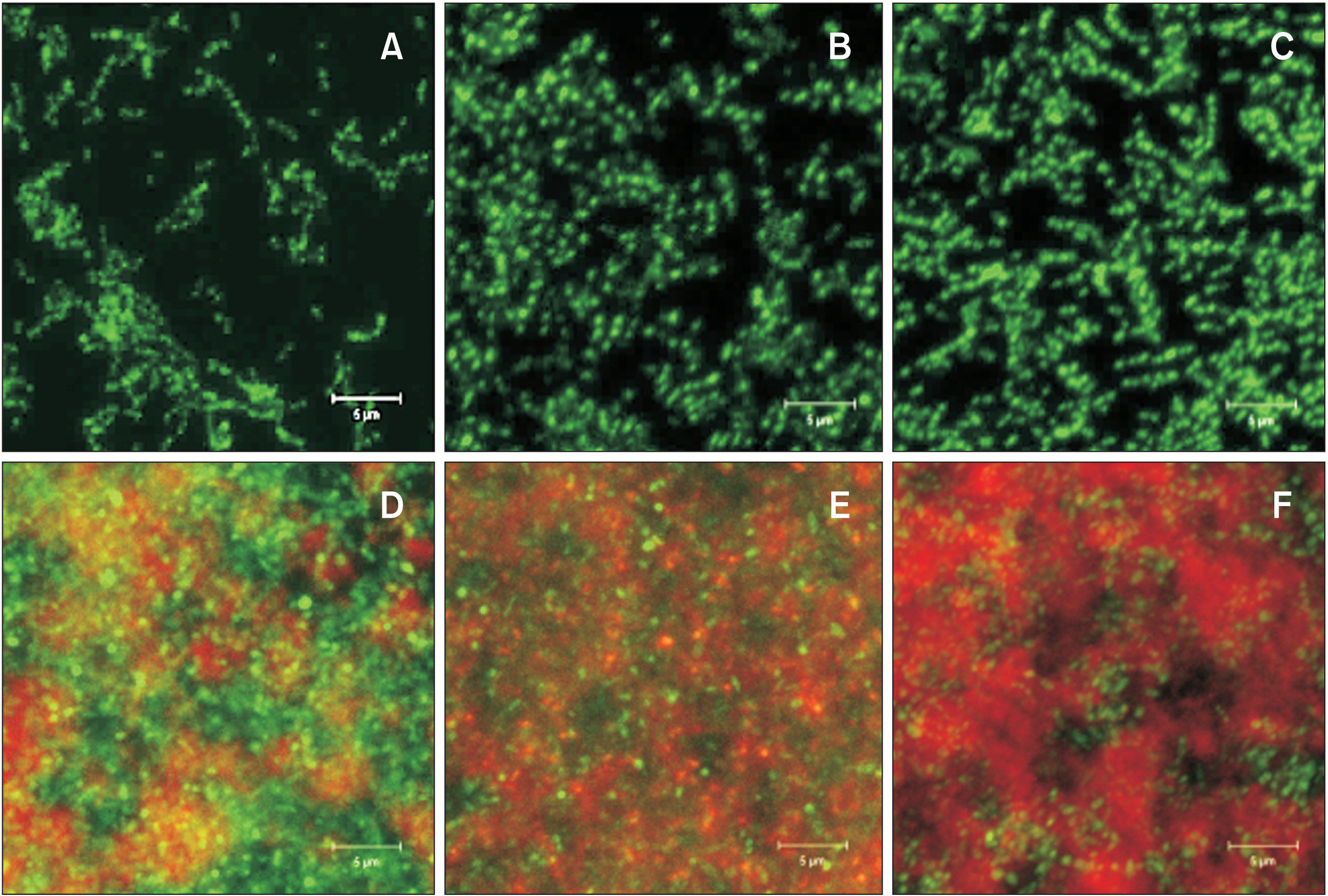

Article20. Jung WS, Kim K, Cho S, Ahn SJ. 2016; Adhesion of periodontal pathogens to self-ligating orthodontic brackets: an in-vivo prospective study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 150:467–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.02.023. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.02.023. PMID: 27585775.

Article21. Kim K, Jung WS, Cho S, Ahn SJ. 2016; Changes in salivary periodontal pathogens after orthodontic treatment: an in vivo prospective study. Angle Orthod. 86:998–1003. https://doi.org/10.2319/070615-450.1. DOI: 10.2319/070615-450.1. PMCID: PMC8597347.

Article22. Ahn SJ, Kho HS, Kim KK, Nahm DS. 2003; Adhesion of oral streptococci to experimental bracket pellicles from glandular saliva. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 124:198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00346-9. DOI: 10.1016/S0889-5406(03)00346-9. PMID: 12923517.

Article23. Lee SJ, Kho HS, Lee SW, Yang WS. 2001; Experimental salivary pellicles on the surface of orthodontic materials. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 119:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1067/mod.2001.110583. DOI: 10.1067/mod.2001.110583. PMID: 11174541.

Article24. Ahn SJ, Kho HS, Lee SW, Nahm DS. 2002; Roles of salivary proteins in the adherence of oral streptococci to various orthodontic brackets. J Dent Res. 81:411–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910208100611. DOI: 10.1177/154405910208100611. PMID: 12097434.

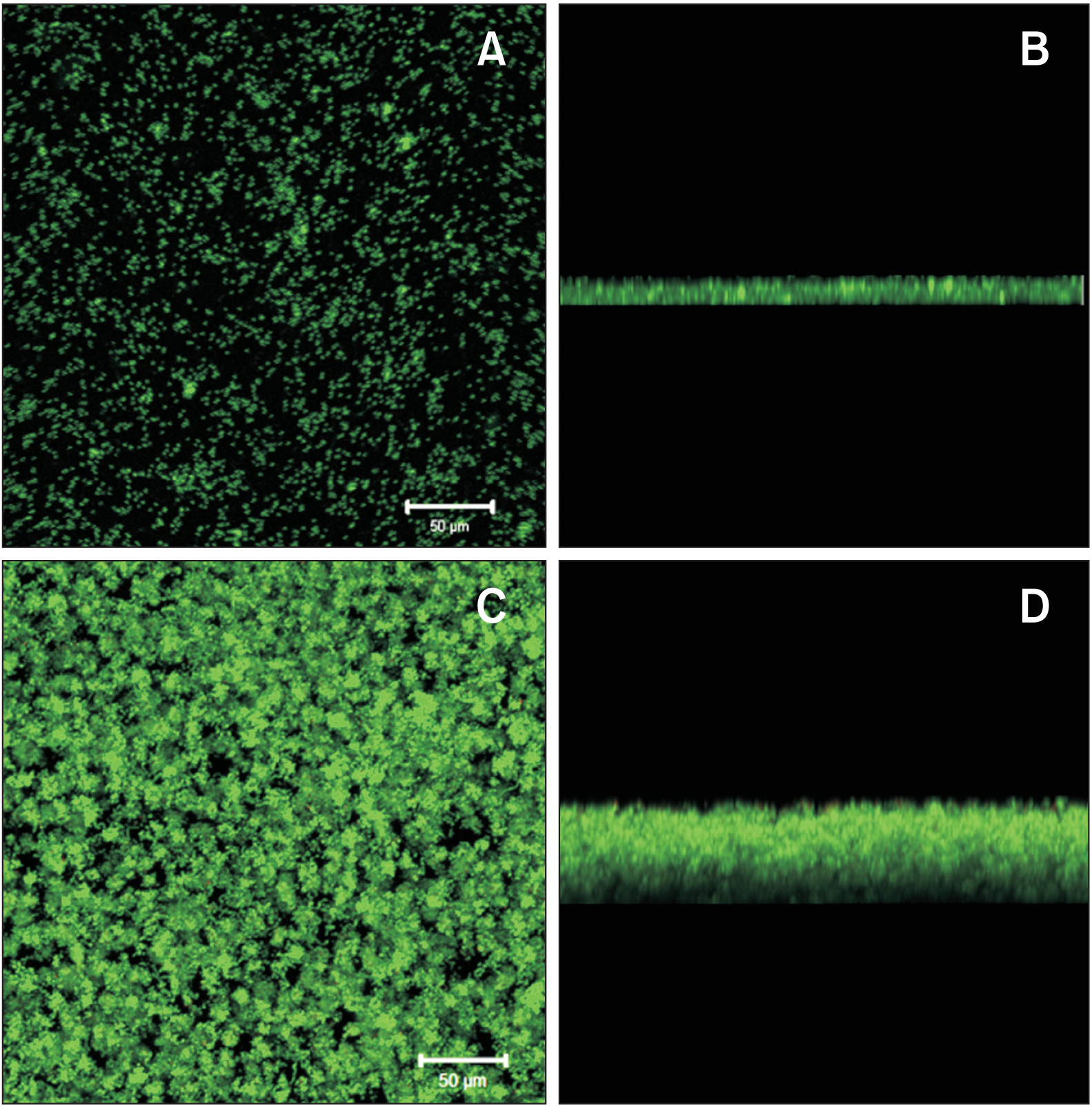

Article25. Ahn SJ, Ahn SJ, Wen ZT, Brady LJ, Burne RA. 2008; Characteristics of biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans in the presence of saliva. Infect Immun. 76:4259–68. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00422-08. DOI: 10.1128/IAI.00422-08. PMID: 18625741. PMCID: PMC2519434.

Article26. Burne RA, Quivey RG Jr, Marquis RE. 1999; Physiologic homeostasis and stress responses in oral biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 310:441–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10035-1. DOI: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)10035-1. PMID: 10547811.

Article27. ten Cate JM. 2006; Biofilms, a new approach to the microbiology of dental plaque. Odontology. 94:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-006-0063-3. DOI: 10.1007/s10266-006-0063-3. PMID: 16998612.

Article28. Burne RA. 1998; Oral streptococci... products of their environment. J Dent Res. 77:445–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345980770030301. DOI: 10.1177/00220345980770030301. PMID: 9496917.

Article29. Park JW, An JS, Lim WH, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2019; Microbial changes in biofilms on composite resins with different surface roughness: an in vitro study with a multispecies biofilm model. J Prosthet Dent. 122:493.e1–493.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.08.009. DOI: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.08.009. PMID: 31648793.

Article30. Bowen WH, Burne RA, Wu H, Koo H. 2018; Oral biofilms: pathogens, matrix, and polymicrobial interactions in microenvironments. Trends Microbiol. 26:229–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.008. DOI: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.008. PMID: 29097091. PMCID: PMC5834367.

Article31. Jakubovics NS, Goodman SD, Mashburn-Warren L, Stafford GP, Cieplik F. 2021; The dental plaque biofilm matrix. Periodontol 2000. 86:32–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12361. DOI: 10.1111/prd.12361. PMID: 33690911. PMCID: PMC9413593.

Article32. Ahn SJ, Ahn SJ, Browngardt CM, Burne RA. 2009; Changes in biochemical and phenotypic properties of Streptococcus mutans during growth with aeration. Appl Environ Microbiol. 75:2517–27. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02367-08. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02367-08. PMID: 19251884. PMCID: PMC2675223.

Article33. Yang IH, Lim BS, Park JR, Hyun JY, Ahn SJ. 2011; Effect of orthodontic bonding steps on the initial adhesion of mutans streptococci in the presence of saliva. Angle Orthod. 81:326–33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21208087/. DOI: 10.2319/062210-343.1. PMID: 21208087. PMCID: PMC8925257.

Article34. O'Reilly MM, Featherstone JD. 1987; Demineralization and remineralization around orthodontic appliances: an in vivo study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 92:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-5406(87)90293-9. DOI: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90293-9. PMID: 3300270.35. Collys K, Cleymaet R, Coomans D, Slop D. 1991; Acid-etched enamel surfaces after 24 h exposure to calcifying media in vitro and in vivo. J Dent. 19:230–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0300-5712(91)90124-h. DOI: 10.1016/0300-5712(91)90124-H. PMID: 1787212.

Article36. Sideridou I, Tserki V, Papanastasiou G. 2002; Effect of chemical structure on degree of conversion in light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials. 23:1819–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00308-8. DOI: 10.1016/S0142-9612(01)00308-8. PMID: 11950052.

Article37. Polydorou O, König A, Hellwig E, Kümmerer K. 2009; Long-term release of monomers from modern dental-composite materials. Eur J Oral Sci. 117:68–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00594.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00594.x. PMID: 19196321.

Article38. Busscher HJ, Rinastiti M, Siswomihardjo W, van der Mei HC. 2010; Biofilm formation on dental restorative and implant materials. J Dent Res. 89:657–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510368644. DOI: 10.1177/0022034510368644. PMID: 20448246.

Article39. Kim K, An JS, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2019; Effect of bisphenol A glycol methacrylate on virulent properties of Streptococcus mutans UA159. Caries Res. 53:84–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490197. DOI: 10.1159/000490197. PMID: 29961075.

Article40. Kim K, Kim JN, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2021; Urethane dimethacrylate influences the cariogenic properties of Streptococcus mutans. Materials (Basel). 14:1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14041015. DOI: 10.3390/ma14041015. PMID: 33669956. PMCID: PMC7924865. PMID: 7aa8acbeae094385802eca3411e5a4ac.

Article41. Chung SH, Cho S, Kim K, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2017; Antimicrobial and physical characteristics of orthodontic primers containing antimicrobial agents. Angle Orthod. 87:307–12. https://doi.org/10.2319/052516-416.1. DOI: 10.2319/052516-416.1. PMID: 27598781. PMCID: PMC8384363.

Article42. Özel MB, Tüzüner T, Güplü ZA, Coleman NJ, Hurt AP, Buruk CK. 2017; The antibacterial activity and release of quaternary ammonium compounds in an orthodontic primer. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 30:141–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29750238/.43. Oz AZ, Oz AA, Yazicioglu S, Sancaktar O. 2019; Effectiveness of an antibacterial primer used with adhesive-coated brackets on enamel demineralization around brackets: an in vivo study. Prog Orthod. 20:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-019-0271-3. DOI: 10.1186/s40510-019-0271-3. PMID: 30982931. PMCID: PMC6462439. PMID: 2c219361e6f640369ff0d2e6bf1c159e.

Article44. Faltermeier A, Bürgers R, Rosentritt M. 2008; Bacterial adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to esthetic bracket materials. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 133(4 Suppl):S99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.03.024. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.03.024. PMID: 18407028.

Article45. Papaioannou W, Gizani S, Nassika M, Kontou E, Nakou M. 2007; Adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to different types of brackets. Angle Orthod. 77:1090–5. https://doi.org/10.2319/091706-375.1. DOI: 10.2319/091706-375.1. PMID: 18004916.

Article46. Lim BS, Kim BH, Shon WJ, Ahn SJ. 2020; Effects of caries activity on compositions of mutans streptococci in saliva-induced biofilm formed on bracket materials. Materials (Basel). 13:4764. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13214764. DOI: 10.3390/ma13214764. PMID: 33114489. PMCID: PMC7663262.

Article47. Ionescu A, Wutscher E, Brambilla E, Schneider-Feyrer S, Giessibl FJ, Hahnel S. 2012; Influence of surface properties of resin-based composites on in vitro Streptococcus mutans biofilm development. Eur J Oral Sci. 120:458–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00983.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00983.x. PMID: 22985005.

Article48. Skilbeck MG, Mei L, Mohammed H, Cannon RD, Farella M. 2022; The effect of ligation methods on biofilm formation in patients undergoing multi-bracketed fixed orthodontic therapy - a systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res. 25:14–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr.12503. DOI: 10.1111/ocr.12503. PMID: 34042260.

Article49. Gwinnett AJ, Ceen RF. 1979; Plaque distribution on bonded brackets: a scanning microscope study. Am J Orthod. 75:667–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9416(79)90098-8. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9416(79)90098-8. PMID: 377979.

Article50. Sukontapatipark W, el-Agroudi MA, Selliseth NJ, Thunold K, Selvig KA. 2001; Bacterial colonization associated with fixed orthodontic appliances. A scanning electron microscopy study. Eur J Orthod. 23:475–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/23.5.475. DOI: 10.1093/ejo/23.5.475. PMID: 11668867.

Article51. Carey CM. 2014; Focus on fluorides: update on the use of fluoride for the prevention of dental caries. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 14 Suppl:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.004. DOI: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.004. PMID: 24929594. PMCID: PMC4058575.

Article52. Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V. 2007; Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults. J Dent Res. 86:410–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910708600504. DOI: 10.1177/154405910708600504. PMID: 17452559.

Article53. O'Mullane DM, Baez RJ, Jones S, Lennon MA, Petersen PE, Rugg-Gunn AJ, et al. 2016; Fluoride and Oral Health. Community Dent Health. 33:69–99. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_3707O'Mullane31. PMID: 27352462.54. Ogaard B. 1990; Effects of fluoride on caries development and progression in vivo. J Dent Res. 69 Spec No:813–9. discussion 820–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345900690S155. DOI: 10.1177/00220345900690S155. PMID: 2179345.

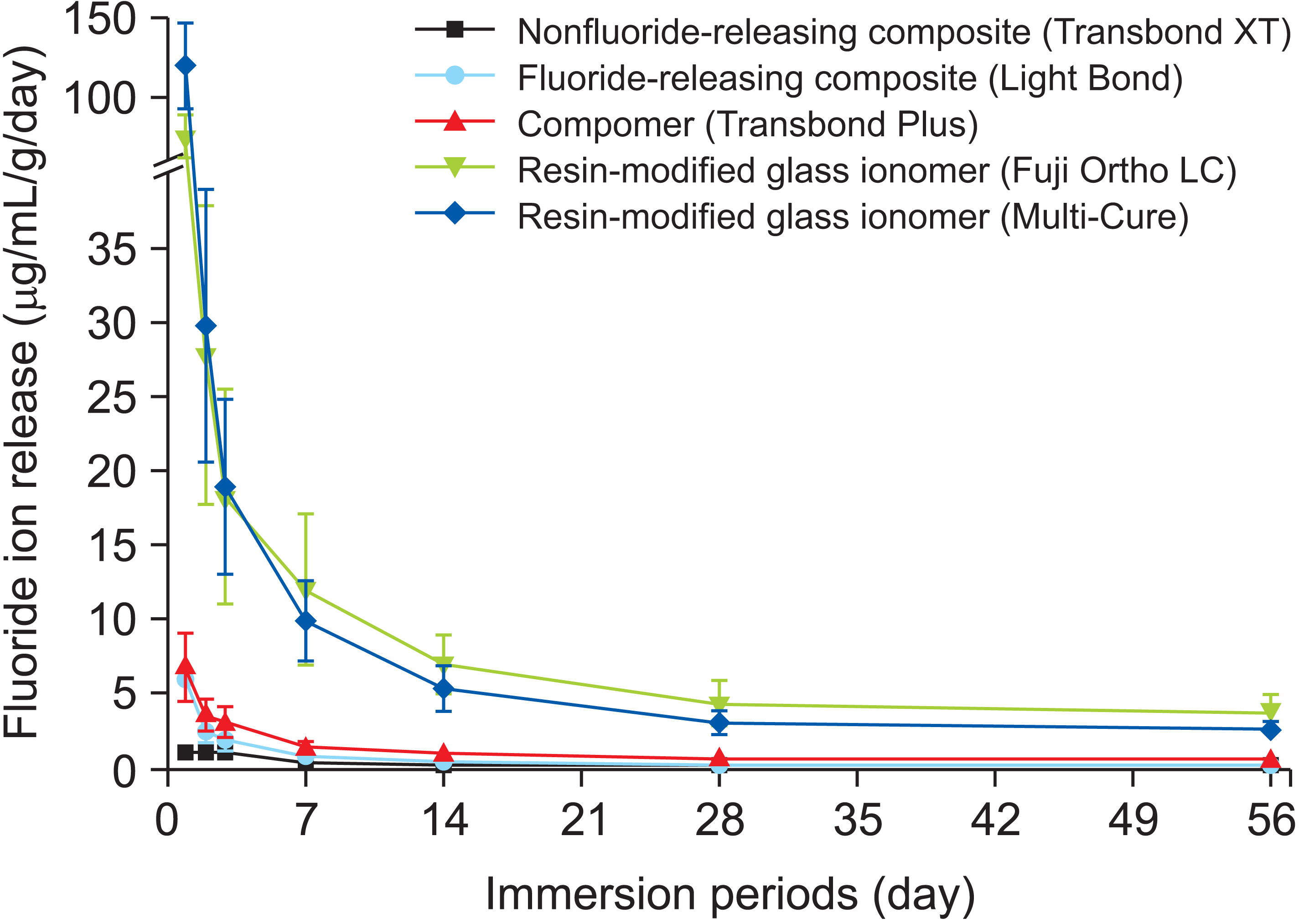

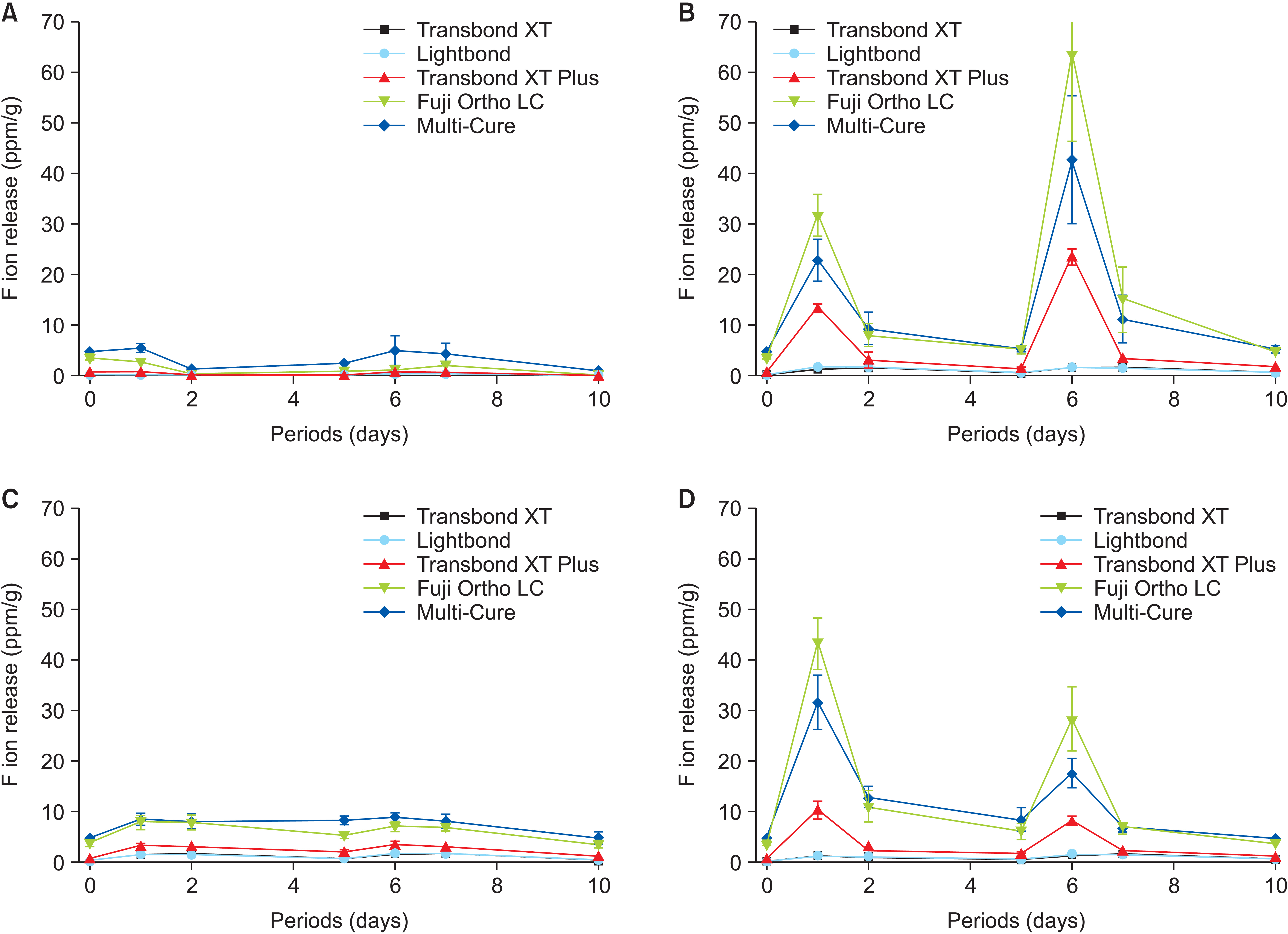

Article55. Ahn SJ, Lee SJ, Lee DY, Lim BS. 2011; Effects of different fluoride recharging protocols on fluoride ion release from various orthodontic adhesives. J Dent. 39:196–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2010.12.003. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.12.003. PMID: 21147194.

Article56. Lim BS, Lee SJ, Lim YJ, Ahn SJ. 2011; Effects of periodic fluoride treatment on fluoride ion release from fresh orthodontic adhesives. J Dent. 39:788–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2011.08.011. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.08.011. PMID: 21896303.

Article57. Fukazawa M, Matsuya S, Yamane M. 1990; The mechanism for erosion of glass-ionomer cements in organic-acid buffer solutions. J Dent Res. 69:1175–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345900690051001. DOI: 10.1177/00220345900690051001. PMID: 2335651.

Article58. Dionysopoulos D. 2016; Effect of digluconate chlorhexidine on bond strength between dental adhesive systems and dentin: a systematic review. J Conserv Dent. 19:11–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-0707.173185. DOI: 10.4103/0972-0707.173185. PMID: 26957786. PMCID: PMC4760005.

Article59. Chen L, Suh BI, Yang J. 2018; Antibacterial dental restorative materials: a review. Am J Dent. 31(Sp Is B):6B–12B. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31099206/. PMID: 31099206.60. Lim BS, Cheng Y, Lee SP, Ahn SJ. 2013; Chlorhexidine release from orthodontic adhesives after topical chlorhexidine treatment. Eur J Oral Sci. 121(3 Pt 1):211–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/eos.12033. DOI: 10.1111/eos.12033. PMID: 23659245.

Article61. Ryu HS, Kim YI, Lim BS, Lim YJ, Ahn SJ. 2015; Chlorhexidine uptake and release from modified titanium surfaces and its antimicrobial activity. J Periodontol. 86:1268–75. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2015.150075. DOI: 10.1902/jop.2015.150075. PMID: 26156675.

Article62. Ahn SJ, Lee SJ, Kook JK, Lim BS. 2009; Experimental antimicrobial orthodontic adhesives using nanofillers and silver nanoparticles. Dent Mater. 25:206–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2008.06.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.06.002. PMID: 18632145.

Article63. Liu Y, Zhang L, Niu LN, Yu T, Xu HHK, Weir MD, et al. 2018; Antibacterial and remineralizing orthodontic adhesive containing quaternary ammonium resin monomer and amorphous calcium phosphate nanoparticles. J Dent. 72:53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2018.03.004. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.03.004. PMID: 29534887.

Article64. Degrazia FW, Altmann ASP, Ferreira CJ, Arthur RA, Leitune VCB, Samuel SMW, et al. 2019; Evaluation of an antibacterial orthodontic adhesive incorporated with niobium-based bioglass: an in situ study. Braz Oral Res. 33:e010. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0010. DOI: 10.1590/1807-3107bor-2019.vol33.0010. PMID: 30892409. PMID: f7f278c492e14af38aed3a5d7e673d94.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A study of enamel demineralization related to bonded orthodontic bracket and improved method of enamel demineralization: in vivo study

- Comparison of Prevention Methods against Enamel Demineralization adjacent to Orthodontic Bracket Using Fluoride

- The effects of a sealant resin on enamel demineralization in orthodontic bracket bonding

- The effects of fluoride releasing orthodontic sealants on the prevention and the progressive inhibition of enamel demineralization in vitro

- Effect of fluoride releasing orthodontic sealants on enamel demineralization in vitro