Ann Rehabil Med.

2023 Oct;47(5):403-425. 10.5535/arm.23042.

Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of a Korean Version of the Information Needs in Cardiac Rehabilitation Scale

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Kangwon National University Hospital, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

- 2Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Sanggye Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Faculty of Health, York University, Toronto, Canada

- 5KITE Research Institute–Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

- KMID: 2548400

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5535/arm.23042

Abstract

Objective

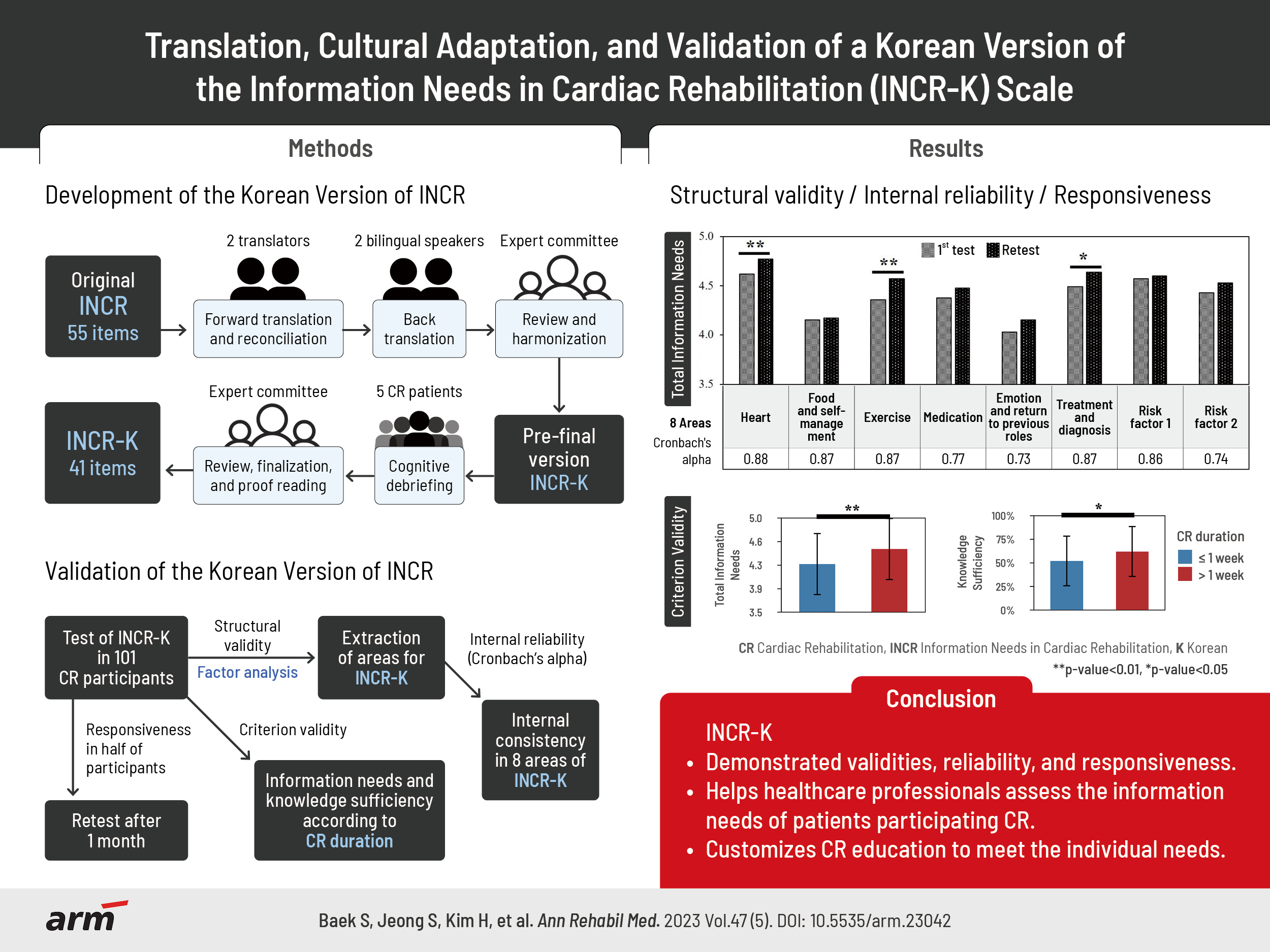

To translate and culturally adapt the Information Needs in Cardiac Rehabilitation (INCR) questionnaire into Korean and perform psychometric validation.

Methods

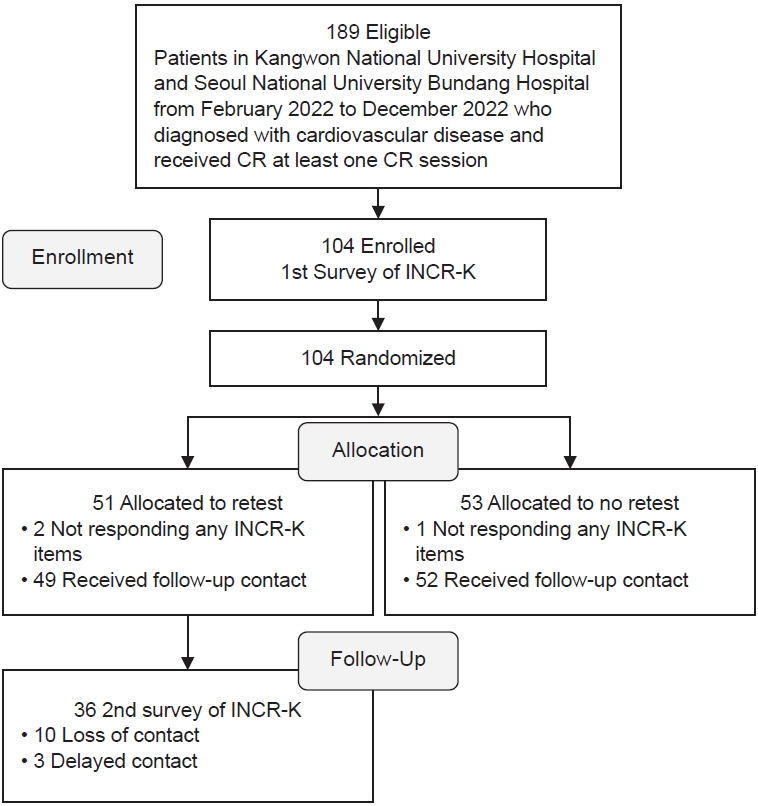

The original English version of the INCR, in which patients are asked to rate the importance of 55 topics, was translated into Korean (INCR-K) and culturally adapted. The INCR-K was tested on 101 cardiac rehabilitation (CR) participants at Kangwon National University Hospital and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital in Korea. Structural validity was assessed using principal component analysis, and Cronbach’s alpha of the areas was computed. Criterion validity was assessed by comparing information needs according to CR duration and knowledge sufficiency according to receipt of education. Half of the participants were randomly selected for 1 month of re-testing to assess their responsiveness.

Results

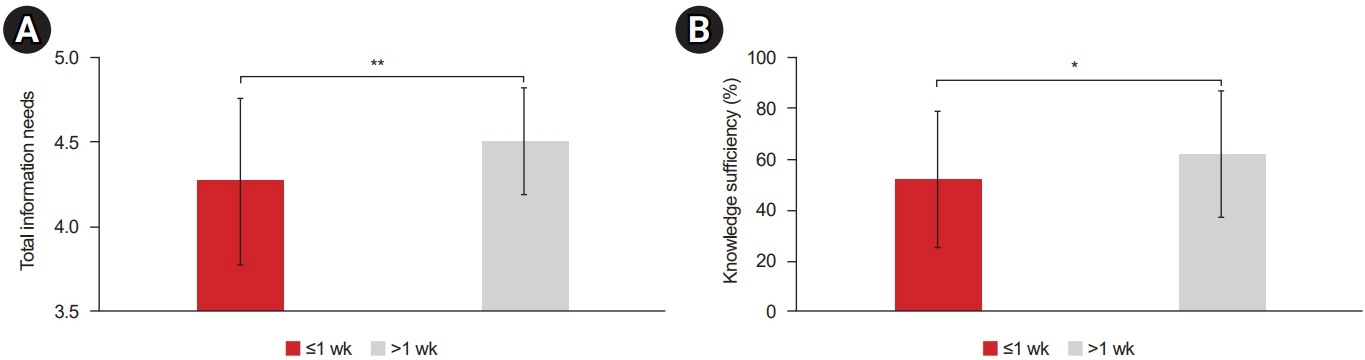

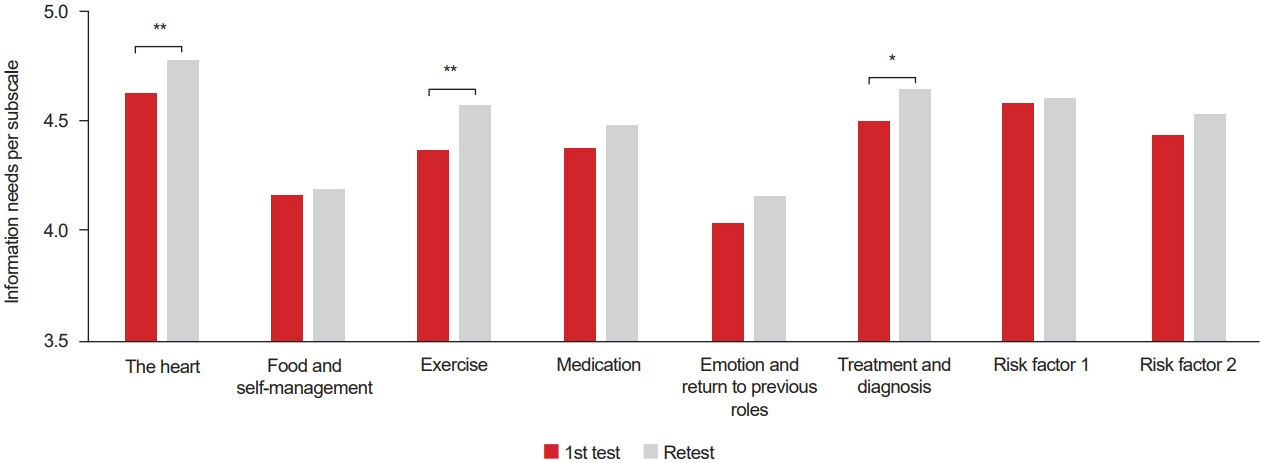

Following cognitive debriefing, the number of items was reduced to 41 and ratings were added to assess participants’ sufficient knowledge of each item. The INCR-K structure comprised eight areas, each with sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha>0.7). Criterion validity was supported by significant differences in mean INCR-K scores based on CR duration and knowledge sufficiency ratings according to receipt of education (p<0.05). Information needs and knowledge sufficiency ratings increased after 1 month of CR, thus supporting responsiveness (p<0.05).

Conclusion

The INCR-K demonstrated adequate face, content, cross-cultural, structural, and criterion validities, internal consistency, and responsiveness. Information needs changed with CR, such that multiple assessments of information needs may be warranted as rehabilitation progresses to facilitate patient-centered education.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020; 396:1204–22. Erratum in: Lancet 2020;396:1562.2. Dibben G, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021; 11:CD001800.

Article3. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:3227–337. Erratum in: Eur Heart J 2022;43:4468.4. Teo K, Lear S, Islam S, Mony P, Dehghan M, Li W, et al. Prevalence of a healthy lifestyle among individuals with cardiovascular disease in high-, middle- and low-income countries: The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. JAMA. 2013; 309:1613–21.

Article5. Moser DK, Dracup KA, Marsden C. Needs of recovering cardiac patients and their spouses: compared views. Int J Nurs Stud. 1993; 30:105–14.

Article6. Larson CO, Nelson EC, Gustafson D, Batalden PB. The relationship between meeting patients’ information needs and their satisfaction with hospital care and general health status outcomes. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996; 8:447–56.

Article7. Scott JT, Thompson DR. Assessing the information needs of post-myocardial infarction patients: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2003; 50:167–77.

Article8. Decker C, Garavalia L, Chen C, Buchanan DM, Nugent K, Shipman A, et al. Acute myocardial infarction patients’ information needs over the course of treatment and recovery. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007; 22:459–65.

Article9. Astin F, Closs SJ, McLenachan J, Hunter S, Priestley C. The information needs of patients treated with primary angioplasty for heart attack: an exploratory study. Patient Educ Couns. 2008; 73:325–32.

Article10. Czar ML, Engler MM. Perceived learning needs of patients with coronary artery disease using a questionnaire assessment tool. Heart Lung. 1997; 26:109–17.

Article11. Lile JB, Buhmann J, Roders S. Development of a learning needs assessment tool for patients with congestive heart failure. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 1999; 11:11–25.

Article12. Grace SL, Turk-Adawi KI, Contractor A, Atrey A, Campbell NR, Derman W, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-resource settings: an international council of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation consensus statement. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016; 59:303–22.

Article13. Pavy B, Barbet R, Carré F, Champion C, Iliou MC, Jourdain P, et al. Therapeutic education in coronary heart disease: position paper from the Working Group of Exercise Rehabilitation and Sport (GERS) and the Therapeutic Education Commission of the French Society of Cardiology. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2013; 106:680–9.

Article14. Ghisi GL, Grace SL, Thomas S, Evans MF, Oh P. Development and psychometric validation of a scale to assess information needs in cardiac rehabilitation: the INCR Tool. Patient Educ Couns. 2013; 91:337–43.

Article15. Ghisi GL, Dos Santos RZ, Bonin CB, Roussenq S, Grace SL, Oh P, et al. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Information Needs in Cardiac Rehabilitation (INCR) scale in Brazil. Heart Lung. 2014; 43:192–7.

Article16. Ghisi GLM, Anchique CV, Fernandez R, Quesada-Chaves D, Gordillo MX, Acosta S, et al. Validation of a Spanish version of the information needs in cardiac rehabilitation scale to assess information needs and preferences in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018; 33:E29–34.

Article17. Ma C, Yang Q, Huang S. Translation and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the information needs in cardiac rehabilitation tool. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2019; 39:331–7.

Article18. Choi SYH, Kim JH. Reliability and validity of Korean-version of information needs in cardiac rehabilitation scale. J Korean Phys Ther. 2022; 34:234–41.

Article19. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010; 63:737–45.20. Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005; 8:94–104.21. Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. 5th ed. Prentice Hall;1998. p. 1–730.22. Pescatello LS; American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 9th ed. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health;2014.23. Shrestha N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am J Appl Math Stat. 2021; 9:4–11.24. Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960; 20:141–51.25. Taherdoost HA, Sahibuddin S, Jalaliyoon NE. Exploratory factor analysis; concepts and theory. Adv Appl Pure Math. 2022; 27:375–82.26. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007; 60:34–42.

Article27. Bjarnason-Wehrens B, McGee H, Zwisler AD, Piepoli MF, Benzer W, Schmid JP, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in Europe: results from the European Cardiac Rehabilitation Inventory Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010; 17:410–8.28. Stockler MR, Osoba D, Goodwin P, Corey P, Tannock IF. Responsiveness to change in health-related quality of life in a randomized clinical trial: a comparison of the Prostate Cancer Specific Quality of Life Instrument (PROSQOLI) with analogous scales from the EORTC QLQ-C30 and a trial specific module. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51:137–45.29. Kirkley A, Griffin S, McLintock H, Ng L. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Am J Sports Med. 1998; 26:764–72.

Article30. Arthur HM, Patterson C, Stone JA. The role of complementary and alternative therapies in cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic evaluation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006; 13:3–9.

Article31. Wood MJ, Stewart RL, Merry H, Johnstone DE, Cox JL. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2003; 145:806–12.

Article32. de Melo Ghisi GL, Grace SL, Thomas S, Evans MF, Sawula H, Oh P. Healthcare providers’ awareness of the information needs of their cardiac rehabilitation patients throughout the program continuum. Patient Educ Couns. 2014; 95:143–50.

Article33. Ghisi GL, Britto R, Motamedi N, Grace SL. Disease-related knowledge in cardiac rehabilitation enrollees: correlates and changes. Patient Educ Couns. 2015; 98:533–9.

Article34. Chan V. Content areas for cardiac teaching: patients’ perceptions of the importance of teaching content after myocardial infarction. J Adv Nurs. 1990; 15:1139–45.

Article35. Timmins F, Kaliszer M. Information needs of myocardial infarction patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003; 2:57–65.

Article36. Wingate S. Post-MI patients’ perceptions of their learning needs. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1990; 9:112–8.

Article37. Serber ER, Todaro JF, Tilkemeier PL, Niaura R. Prevalence and characteristics of multiple psychiatric disorders in cardiac rehabilitation patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009; 29:161–8; quiz 169-70.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Translation, Cross-cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Validation of the Korean-Language Cardiac Rehabilitation Barriers Scale (CRBS-K)

- Korean Cultural Adaptation of WHODAS 2.0 (36-Item Version): Reliability and Linking to ICF

- Reliability and Validity of Korean-Version of Information Needs in Cardiac Rehabilitation Scale

- Translation and validation of the Turkish version of the Psychosocial Impact of Dental Aesthetics Questionnaire

- Cross-cultural Adaptation of the Korean Version Of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)