J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Nov;38(44):e367. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e367.

Regional Disparities in the Infant Mortality Rate in Korea Between 2001 and 2021

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea

- 2Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2547972

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e367

Abstract

- Background

The infant mortality rate (IMR) has been considered an important indicator of the overall public health level. Despite improvements in recent decades, regional inequalities in the IMR have been reported worldwide. However, there are no Korean epidemiological studies on regional disparities in the IMR.

Methods

We extracted causes of death data from the Statistics Korea through the Korean Statistical Information Service database between 2001 and 2021. The total and regional IMRs were calculated to determine regional disparities. Based on causes of death and using Seoul as a reference, the excess infant deaths and population attributable fractions (PAFs) were calculated for 15 other metropolitan cities and provinces. The average annual percent changes by region from 2001 to 2021 were obtained using a joinpoint regression program. To assess inequities in IMR trends, the rate ratios (RRs) and rate differences (RDs) of the 15 regions were calculated by dividing the study period into period 1 (2001–2007), period 2 (2008–2014), and period 3 (2015–2021).

Results

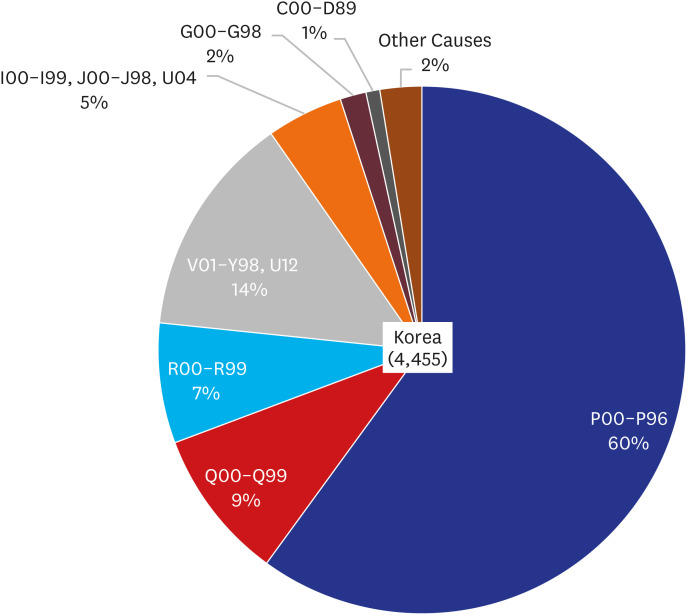

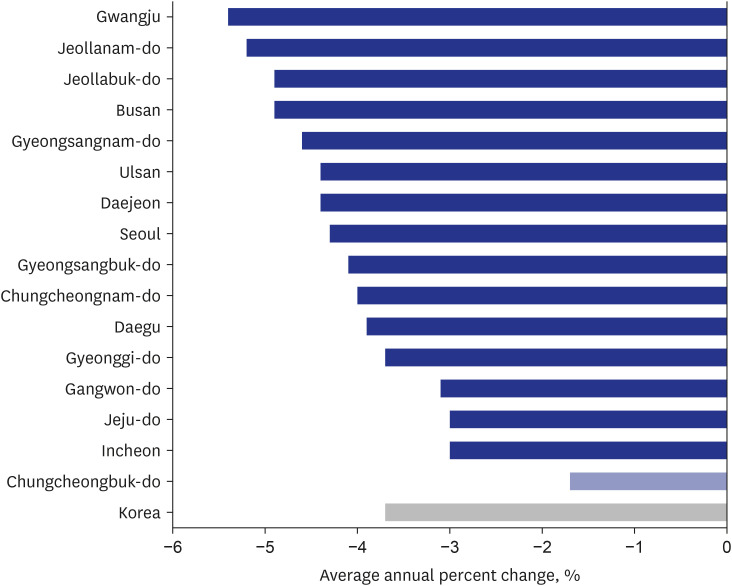

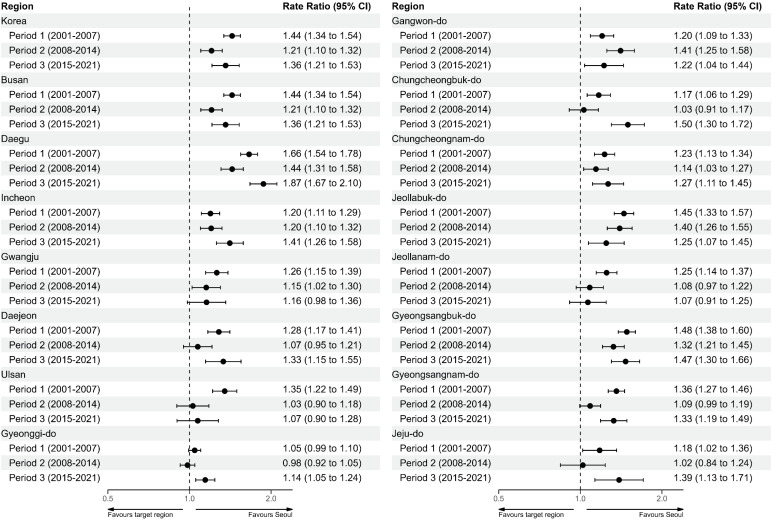

The overall IMR in Korea was 3.64 per 1,000 live births, and the IMRs in the 14 regions were relatively higher than that in Seoul, with RRs ranging from 1.15 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04, 1.27) in Jeju-do to 1.62 (95% CI, 1.54, 1.71) in Daegu, over the total study period. Significant differences in infant deaths by region were observed for all causes of death, with PAFs ranging from 2.2% (95% CI, 1.7, 2.6) in Gyeonggi-do to 38.4% (95% CI, 38.1, 38.6) in Daegu. The leading cause of excess infant deaths was perinatal problems. The IMR disparities in the relative and absolute measures decreased from 1.44 (1.34, 1.54) to 1.21 (1.10, 1.31) for RRs and from 0.79 (0.63, 0.96) to 0.30 (0.15, 0.45) for RDs between periods 1 and 2, followed by an increase from 1.21 (1.10, 1.31) to 1.36 (1.21, 1.53) for RRs and from 0.30 (0.15, 0.45) to 0.51(0.36, 0.67) for RDs between period 2 and 3.

Conclusion

Infant death is associated with place of residence and regional gaps have recently widened again in Korea. An in-depth investigation of the causes of regional disparities in infant mortality is required for effective governmental policies to achieve equality in infant health.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Reidpath DD, Allotey P. Infant mortality rate as an indicator of population health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003; 57(5):344–346. PMID: 12700217.

Article2. Singh GK, Yu SM. Infant mortality in the United States, 1915–2017: large social inequalities have persisted for over a century. Int J MCH AIDS. 2019; 8(1):19–31. PMID: 31049261.

Article3. Hirai AH, Sappenfield WM, Kogan MD, Barfield WD, Goodman DA, Ghandour RM, et al. Contributors to excess infant mortality in the U.S. South. Am J Prev Med. 2014; 46(3):219–227. PMID: 24512860.

Article4. Womack LS, Rossen LM, Hirai AH. Urban-rural infant mortality disparities by race and ethnicity and cause of death. Am J Prev Med. 2020; 58(2):254–260. PMID: 31735480.

Article5. Yu X, Wang Y, Kang L, Miao L, Song X, Ran X, et al. Geographical disparities in infant mortality in the rural areas of China: a descriptive study, 2010–2018. BMC Pediatr. 2022; 22(1):264. PMID: 35549888.

Article6. Joseph KS, Huang L, Dzakpasu S, McCourt C. Regional disparities in infant mortality in Canada: a reversal of egalitarian trends. BMC Public Health. 2009; 9(1):4. PMID: 19128489.

Article7. Mishina H, Hilton JF, Takayama JI. Trends and variations in infant mortality among 47 prefectures in Japan. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013; 19(5):849–854. PMID: 22639950.

Article8. Nath S, Hardelid P, Zylbersztejn A. Are infant mortality rates increasing in England? The effect of extreme prematurity and early neonatal deaths. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021; 43(3):541–550. PMID: 32119086.

Article9. Eun SJ. Trends and disparities in avoidable, treatable, and preventable mortalities in South Korea, 2001–2020: comparison of capital and non-capital areas. Epidemiol Health. 2022; 44:e2022067. PMID: 35989656.

Article10. Go DS, Kim YE, Radnaabaatar M, Jung Y, Jung J, Yoon SJ. Regional differences in years of life lost in Korea from 1997 to 2015. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 34(Suppl 1):e91. PMID: 30923494.

Article11. Chang JY, Lee KS, Hahn WH, Chung SH, Choi YS, Shim KS, et al. Decreasing trends of neonatal and infant mortality rates in Korea: compared with Japan, USA, and OECD nations. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26(9):1115–1123. PMID: 21935264.

Article12. Choi H, Nho JH, Yi N, Park S, Kang B, Jang H. Maternal, infant, and perinatal mortality statistics and trends in Korea between 2018 and 2020. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2022; 28(4):348–357. PMID: 36617486.

Article13. Chung SH, Choi YS, Bae CW. Changes in the neonatal and infant mortality rate and the causes of death in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2011; 54(11):443–455. PMID: 22253641.

Article14. Lee KJ, Sohn S, Hong K, Kim J, Kim R, et al. Vital Statistics Division, Statistics Korea, Daejeon, Korea. Maternal, infant, and perinatal mortality statistics and trends in Korea between 2009 and 2017. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020; 63(5):623–630. PMID: 32756294.

Article15. Park MS. Standing at the edge of the ‘Demographic Cliff’. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(42):e318. PMID: 36325611.

Article16. Chang YS. Moving forward to improve safety and quality of neonatal intensive care in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33(9):e89. PMID: 29441743.

Article17. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H. Epidemiologic Research: Principles and Quantitative Methods. Belmont, CA, USA: Lifetime Learning Publications;1982.18. Lewer D, Jayatunga W, Aldridge RW, Edge C, Marmot M, Story A, et al. Premature mortality attributable to socioeconomic inequality in England between 2003 and 2018: an observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020; 5(1):e33–e41. PMID: 31813773.

Article19. Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009; 28(29):3670–3682. PMID: 19856324.

Article20. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000; 19(3):335–351. PMID: 10649300.

Article21. Nakamura Y, Nagai M, Yanagawa H. A characteristic change in infant mortality rate decrease in Japan. Public Health. 1991; 105(2):145–151. PMID: 2068238.

Article22. Flenady V, Middleton P, Smith GC, Duke W, Erwich JJ, Khong TY, et al. Stillbirths: the way forward in high-income countries. Lancet. 2011; 377(9778):1703–1717. PMID: 21496907.

Article23. Peelen MJ, Kazemier BM, Ravelli AC, De Groot CJ, Van Der Post JA, Mol BW, et al. Impact of fetal gender on the risk of preterm birth, a national cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016; 95(9):1034–1041. PMID: 27216473.

Article24. Ravelli AC, Tromp M, Eskes M, Droog JC, van der Post JA, Jager KJ, et al. Ethnic differences in stillbirth and early neonatal mortality in The Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011; 65(8):696–701. PMID: 20719806.

Article25. Pillay J, Donovan L, Guitard S, Zakher B, Gates M, Gates A, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2021; 326(6):539–562. PMID: 34374717.26. Joseph KS, Liston RM, Dodds L, Dahlgren L, Allen AC. Socioeconomic status and perinatal outcomes in a setting with universal access to essential health care services. CMAJ. 2007; 177(6):583–590. PMID: 17846440.

Article27. Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, Das A, Hintz SR, Stoll BJ, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(19):1801–1811. PMID: 25946279.

Article28. Sugai MK, Gilmour S, Ota E, Shibuya K. Trends in perinatal mortality and its risk factors in Japan: analysis of vital registration data, 1979–2010. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1):46681. PMID: 28440334.

Article29. Almossawi O, O’Brien S, Parslow R, Nadel S, Palla L. A study of sex difference in infant mortality in UK pediatric intensive care admissions over an 11-year period. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):21838. PMID: 34750426.

Article30. Sidebotham P, Fraser J, Covington T, Freemantle J, Petrou S, Pulikottil-Jacob R, et al. Understanding why children die in high-income countries. Lancet. 2014; 384(9946):915–927. PMID: 25209491.

Article31. Chun H, Das Gupta M. Gender discrimination in sex selective abortions and its transition in South Korea. Womens Stud Int Forum. 2009; 32(2):89–97.

Article32. Chun H, Kim IH, Khang YH. Trends in sex ratio at birth according to parental social positions: results from vital statistics birth, 1981–2004 in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2009; 42(2):143–150. PMID: 19349745.

Article33. Caughey AB. Association between income and perinatal mortality in The Netherlands across gestational age. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2022; 77(5):259–261.

Article34. Trinh NTH, de Visme S, Cohen JF, Bruckner T, Lelong N, Adnot P, et al. Recent historic increase of infant mortality in France: a time-series analysis, 2001 to 2019. Lancet Regional Health-Europe. 2022; 16:100339. PMID: 35252944.

Article35. Yun JW, Kim YJ, Son M. Regional deprivation index and socioeconomic inequalities related to infant deaths in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016; 31(4):568–578. PMID: 27051241.

Article36. Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW, Blackmon L. Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010; 304(9):992–1000. PMID: 20810377.

Article37. Minion SC, Krans EE, Brooks MM, Mendez DD, Haggerty CL. Association of driving distance to maternity hospitals and maternal and perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2022; 140(5):812–819. PMID: 36201778.

Article38. Målqvist M, Sohel N, Do TT, Eriksson L, Persson LA. Distance decay in delivery care utilisation associated with neonatal mortality. A case referent study in northern Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2010; 10(1):762. PMID: 21144058.

Article39. Karra M, Fink G, Canning D. Facility distance and child mortality: a multi-country study of health facility access, service utilization, and child health outcomes. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(3):817–826. PMID: 27185809.

Article40. Shim JW, Kim MJ, Kim EK, Park HK, Song ES, Lee SM, et al. The impact of neonatal care resources on regional variation in neonatal mortality among very low birthweight infants in Korea. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013; 27(2):216–225. PMID: 23374067.

Article41. Song IG, Shin SH, Kim HS. Improved regional disparities in neonatal care by government-led policies in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33(6):e43. PMID: 29349938.

Article42. Won TY, Kang BS, Im TH, Choi HJ. The study of accuracy of death statistics. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2007; 18(3):256–262.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Trends and disparities in avoidable, treatable, and preventable mortalities in South Korea, 2001-2020: comparison of capital and non-capital areas

- Improved Regional Disparities in Neonatal Care by Government-led Policies in Korea

- Regional Disparity of Cardiovascular Mortality and Its Determinants

- Factors affecting regional disparities in the number of teeth sealed with pit and fissure sealants: information for the National Health Insurance

- Mortality and Disparities of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Stroke in Korea, 2008–2019