Intest Res.

2023 Oct;21(4):443-451. 10.5217/ir.2023.00107.

Summary and comparison of recently updated post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2547194

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2023.00107

Abstract

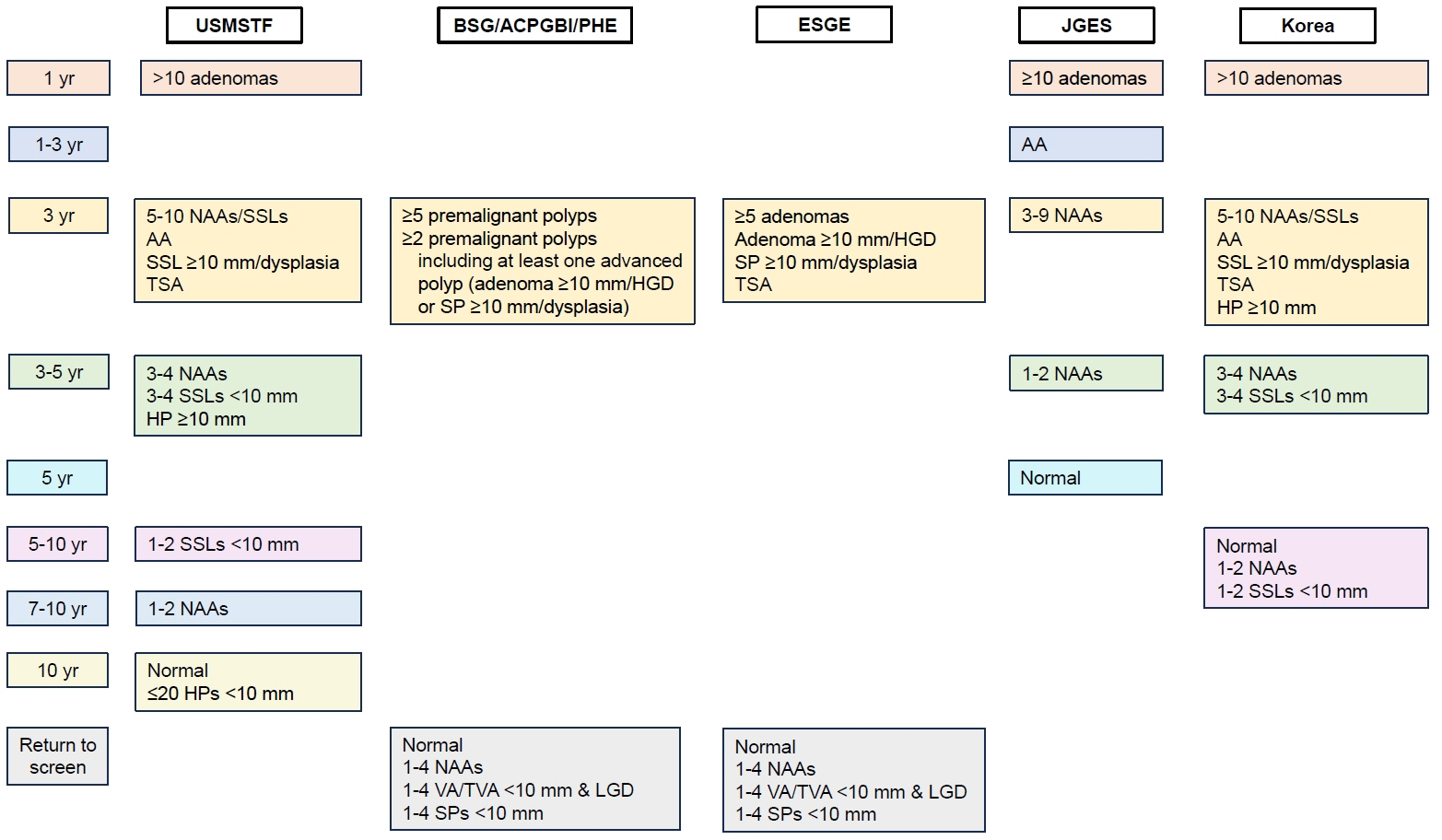

- Recently, updated guidelines for post-polypectomy surveillance have been published by the U.S. Multi‐Society Task Force (USMSTF), the British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland/Public Health England (BSG/ACPGBI/PHE), the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES), and the Korean Multi-Society Taskforce Committee. This review summarizes and compares the updated recommendations of these 5 guidelines. There are some differences between the guidelines for the recommended post-polypectomy surveillance intervals. In particular, there are prominent differences between the guidelines for 1–4 tubular adenomas < 10 mm with low-grade dysplasia (nonadvanced adenomas [NAAs]) and tubulovillous or villous adenomas. The USMSTF, JGES, and Korean guidelines recommend colonoscopic surveillance for patients with 1–4 NAAs and those with tubulovillous or villous adenomas, whereas the BSG/ACPGBI/PHE and ESGE guidelines do not recommend endoscopic surveillance for such patients. Surveillance recommendations for patients with serrated polyps (SPs) are limited. Although the USMSTF guidelines provide specific recommendations for patients who have undergone SPs removal, these are weak and based on very lowquality evidence. Future studies should examine this topic to better guide the surveillance recommendations for patients with SPs. For countries that do not have separate guidelines, we hope that this review article will help select the most appropriate guidelines as per each country’s healthcare environment.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Screening and surveillance for hereditary colorectal cancer

Hee Man Kim, Tae Il Kim

Intest Res. 2024;22(2):119-130. doi: 10.5217/ir.2023.00112.

Reference

-

1. Rubio CA. Two intertwined compartments coexisting in sporadic conventional colon adenomas. Intest Res. 2021; 19:12–20.

Article2. Kim SY, Kim TI. Serrated neoplasia pathway as an alternative route of colorectal cancer carcinogenesis. Intest Res. 2018; 16:358–365.

Article3. Nguyen LH, Goel A, Chung DC. Pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:291–302.

Article4. Hong SW, Byeon JS. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of early colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2022; 20:281–290.

Article5. Park CH, Yang DH, Kim JW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for endoscopic resection of early gastrointestinal cancer. Intest Res. 2021; 19:127–157.

Article6. Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020; 115:415–434.

Article7. Rutter MD, East J, Rees CJ, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland/Public Health England post-polypectomy and post-colorectal cancer resection surveillance guidelines. Gut. 2020; 69:201–223.

Article8. Hassan C, Antonelli G, Dumonceau JM, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline: update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020; 52:687–700.

Article9. Saito Y, Oka S, Kawamura T, et al. Colonoscopy screening and surveillance guidelines. Dig Endosc. 2021; 33:486–519.

Article10. Kim SY, Kwak MS, Yoon SM, et al. Korean Guidelines for Postpolypectomy Colonoscopic Surveillance: 2022 revised edition. Intest Res. 2023; 21:20–42.

Article11. Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012; 143:844–857.

Article12. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut. 2010; 59:666–689.

Article13. Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau JM, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2013; 45:842–851.

Article14. Monahan KJ, Bradshaw N, Dolwani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of hereditary colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG). Gut. 2020; 69:411–444.

Article15. Fairley KJ, Li J, Komar M, Steigerwalt N, Erlich P. Predicting the risk of recurrent adenoma and incident colorectal cancer based on findings of the baseline colonoscopy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014; 5:e64.

Article16. van Heijningen EM, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuipers EJ, et al. Features of adenoma and colonoscopy associated with recurrent colorectal neoplasia based on a large community-based study. Gastroenterology. 2013; 144:1410–1418.

Article17. Atkin W, Wooldrage K, Brenner A, et al. Adenoma surveillance and colorectal cancer incidence: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017; 18:823–834.

Article18. Atkin W, Brenner A, Martin J, et al. The clinical effectiveness of different surveillance strategies to prevent colorectal cancer in people with intermediate-grade colorectal adenomas: a retrospective cohort analysis, and psychological and economic evaluations. Health Technol Assess. 2017; 21:1–536.

Article19. Wieszczy P, Kaminski MF, Franczyk R, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence and mortality after removal of adenomas during screening colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:875–883.

Article20. Mahajan D, Downs-Kelly E, Liu X, et al. Reproducibility of the villous component and high-grade dysplasia in colorectal adenomas <1 cm: implications for endoscopic surveillance. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013; 37:427–433.

Article21. Belderbos TD, Leenders M, Moons LM, Siersema PD. Local recurrence after endoscopic mucosal resection of nonpedunculated colorectal lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2014; 46:388–402.

Article22. Rex KD, Vemulapalli KC, Rex DK. Recurrence rates after EMR of large sessile serrated polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 82:538–541.

Article23. Pellise M, Burgess NG, Tutticci N, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for large serrated lesions in comparison with adenomas: a prospective multicentre study of 2000 lesions. Gut. 2017; 66:644–653.

Article24. Crockett SD, Nagtegaal ID. Terminology, molecular features, epidemiology, and management of serrated colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019; 157:949–966.

Article25. Niv Y. Changing pathological diagnosis from hyperplastic polyp to sessile serrated adenoma: systematic review and metaanalysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 29:1327–1331.

Article26. Jaravaza DR, Rigby JM. Hyperplastic polyp or sessile serrated lesion? The contribution of serial sections to reclassification. Diagn Pathol. 2020; 15:140.

Article27. Boylan KE, Kanth P, Delker D, et al. Three pathologic criteria for reproducible diagnosis of colonic sessile serrated lesion versus hyperplastic polyp. Hum Pathol. 2023; 137:25–35.

Article28. Jung YS, Park JH, Park CH. Serrated polyps and the risk of metachronous colorectal advanced neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022; 20:31–43.

Article29. Mankaney G, Rouphael C, Burke CA. Serrated polyposis syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 18:777–779.

Article30. Patel SG, May FP, Anderson JC, et al. Updates on age to start and stop colorectal cancer screening: recommendations from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022; 162:285–299.

Article31. Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015; 150:17–22.

Article32. Siegel RL, Medhanie GA, Fedewa SA, Jemal A. State variation in early-onset colorectal cancer in the United States, 1995-2015. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019; 111:1104–1106.

Article33. Byeon JS, Yang SK, Kim TI, et al. Colorectal neoplasm in asymptomatic Asians: a prospective multinational multicenter colonoscopy survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 65:1015–1022.

Article34. Park HW, Byeon JS, Yang SK, et al. Colorectal neoplasm in asymptomatic average-risk Koreans: the KASID prospective multicenter colonoscopy survey. Gut Liver. 2009; 3:35–40.

Article35. Hong SN, Kim JH, Choe WH, et al. Prevalence and risk of colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic, average-risk screenees 40 to 49 years of age. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 72:480–489.

Article36. Chung SJ, Kim YS, Yang SY, et al. Prevalence and risk of colorectal adenoma in asymptomatic Koreans aged 40-49 years undergoing screening colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 25:519–525.

Article37. Chang LC, Wu MS, Tu CH, Lee YC, Shun CT, Chiu HM. Metabolic syndrome and smoking may justify earlier colorectal cancer screening in men. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 79:961–969.

Article38. Jung YS, Ryu S, Chang Y, et al. Risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in persons aged 30 to 39 years and 40 to 49 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81:637–645.

Article39. Koo JE, Kim KJ, Park HW, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of advanced colorectal neoplasms in asymptomatic Korean people between 40 and 49years of age. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 32:98–105.

Article40. Kim KO, Yang HJ, Cha JM, et al. Risks of colorectal advanced neoplasia in young adults versus those of screening colonoscopy in patients aged 50 to 54 years. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 32:1825–1831.

Article41. Kim NH, Jung YS, Yang HJ, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic young adults (20-39 years old). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 17:115–122.

Article42. Jung YS, Park JH, Park CH. Comparison of risk of metachronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in patients with sporadic adenomas aged < 50 versus ≥ 50 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med. 2021; 11:120.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Post-polypectomy surveillance: the present and the future

- Strategy for post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: focus on the revised Korean guidelines

- A Survey on the Interval of Post-polypectomy Surveillance Colonoscopy

- Korean Guidelines for Postpolypectomy Colonoscopic Surveillance: 2022 Revision

- Optimal Colonoscopy Surveillance Interval after Polypectomy