J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Oct;38(41):e316. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e316.

Textural and Volumetric Changes of the Temporal Lobes in Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia and Alzheimer’s Disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Brain and Cognitive Science, Seoul National University College of Natural Science, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Health Science and Technology, Graduate School of Convergence Science and Technology, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Neuropsychiatry, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Workplace Mental Health Institute, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Neuropsychiatry, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Neuropsychiatry, Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju, Korea

- 8Department of Radiology, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2547174

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e316

Abstract

- Background

Texture analysis may capture subtle changes in the gray matter more sensitively than volumetric analysis. We aimed to investigate the patterns of neurodegeneration in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by comparing the temporal gray matter texture and volume between cognitively normal controls and older adults with svPPA and AD.

Methods

We enrolled all participants from three university hospitals in Korea. We obtained T1-weighted magnetic resonance images and compared the gray matter texture and volume of regions of interest (ROIs) between the groups using analysis of variance with Bonferroni posthoc comparisons. We also developed models for classifying svPPA, AD and control groups using logistic regression analyses, and validated the models using receiver operator characteristics analysis.

Results

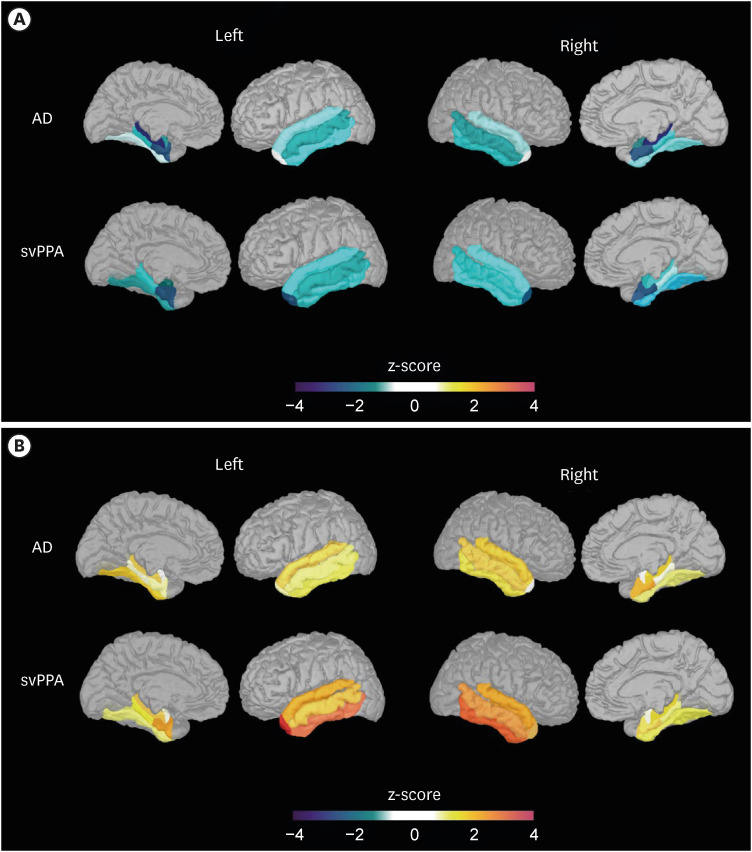

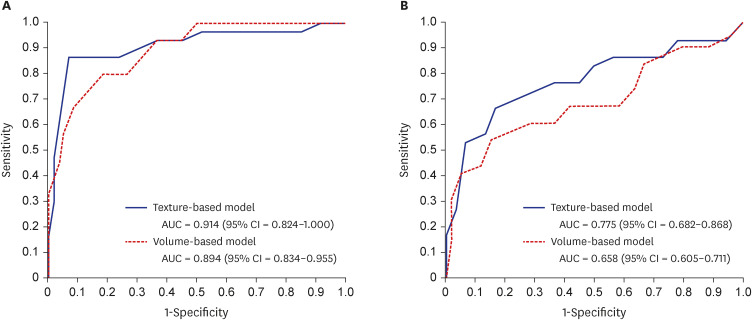

Compared to the AD group, the svPPA group showed lower volumes in five ROIs (bilateral temporal poles, and the left inferior, middle, and superior temporal cortices) and higher texture in these five ROIs and two additional ROIs (right inferior temporal and left entorhinal cortices). The performances of both texture- and volume-based models were good and comparable in classifying svPPA from normal cognition (mean area under the curve [AUC] = 0.914 for texture; mean AUC = 0.894 for volume). However, only the texture-based model achieved a good level of performance in classifying svPPA and AD (mean AUC = 0.775 for texture; mean AUC = 0.658 for volume).

Conclusion

Texture may be a useful neuroimaging marker for early detection of svPPA in older adults and its differentiation from AD.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011; 76(11):1006–1014. PMID: 21325651.2. Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002; 58(11):1615–1621. PMID: 12058088.3. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998; 51(6):1546–1554. PMID: 9855500.4. Greene JD, Baddeley AD, Hodges JR. Analysis of the episodic memory deficit in early Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the doors and people test. Neuropsychologia. 1996; 34(6):537–551. PMID: 8736567.5. Liscic RM, Storandt M, Cairns NJ, Morris JC. Clinical and psychometric distinction of frontotemporal and Alzheimer dementias. Arch Neurol. 2007; 64(4):535–540. PMID: 17420315.6. Davies RR, Graham KS, Xuereb JH, Williams GB, Hodges JR. The human perirhinal cortex and semantic memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2004; 20(9):2441–2446. PMID: 15525284.7. Galton CJ, Patterson K, Graham K, Lambon-Ralph MA, Williams G, Antoun N, et al. Differing patterns of temporal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2001; 57(2):216–225. PMID: 11468305.8. Mummery CJ, Patterson K, Price CJ, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, Hodges JR. A voxel-based morphometry study of semantic dementia: relationship between temporal lobe atrophy and semantic memory. Ann Neurol. 2000; 47(1):36–45. PMID: 10632099.9. Chan D, Fox NC, Scahill RI, Crum WR, Whitwell JL, Leschziner G, et al. Patterns of temporal lobe atrophy in semantic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2001; 49(4):433–442. PMID: 11310620.10. La Joie R, Landeau B, Perrotin A, Bejanin A, Egret S, Pélerin A, et al. Intrinsic connectivity identifies the hippocampus as a main crossroad between Alzheimer’s and semantic dementia-targeted networks. Neuron. 2014; 81(6):1417–1428. PMID: 24656258.11. Pereira JB, Cavallin L, Spulber G, Aguilar C, Mecocci P, Vellas B, et al. Influence of age, disease onset and ApoE4 on visual medial temporal lobe atrophy cut-offs. J Intern Med. 2014; 275(3):317–330. PMID: 24118559.12. Derflinger S, Sorg C, Gaser C, Myers N, Arsic M, Kurz A, et al. Grey-matter atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease is asymmetric but not lateralized. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011; 25(2):347–357. PMID: 21422522.13. Wu X, Wu Y, Geng Z, Zhou S, Wei L, Ji GJ, et al. Asymmetric Differences in the gray matter volume and functional connections of the amygdala are associated with clinical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2020; 14:602. PMID: 32670008.14. Lee S, Lee H, Kim KW. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Magnetic resonance imaging texture predicts progression to dementia due to Alzheimer disease earlier than hippocampal volume. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020; 45(1):7–14. PMID: 31228173.15. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993; 43(11):2412–2414.16. Han JW, Kim TH, Kwak KP, Kim K, Kim BJ, Kim SG, et al. Overview of the Korean longitudinal study on cognitive aging and dementia. Psychiatry Investig. 2018; 15(8):767–774.17. Lee JH, Lee KU, Lee DY, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim JH, et al. Development of the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K): clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002; 57(1):47–53.18. Yoo SW, Kim YS, Noh JS, Oh KS, Kim CH, Namkoong K, et al. Validity of Korean version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety Mood. 2006; 2(1):50–55.19. Lee DY, Lee KU, Lee JH, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim SY, et al. A normative study of the CERAD neuropsychological assessment battery in the Korean elderly. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004; 10(1):72–81. PMID: 14751009.20. Kim TH, Huh Y, Choe JY, Jeong JW, Park JH, Lee SB, et al. Korean version of frontal assessment battery: psychometric properties and normative data. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010; 29(4):363–370. PMID: 20424455.21. Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX, USA: Psychological Corporation;1987.22. Kim JY, Park JH, Lee JJ, Huh Y, Lee SB, Han SK, et al. Standardization of the Korean version of the geriatric depression scale: reliability, validity, and factor structure. Psychiatry Investig. 2008; 5(4):232–238.23. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984; 34(7):939–944. PMID: 6610841.24. Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002; 33(3):341–355. PMID: 11832223.25. Hodges JR, Patterson K. Semantic dementia: a unique clinicopathological syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2007; 6(11):1004–1014. PMID: 17945154.26. Landqvist Waldö M, Frizell Santillo A, Passant U, Zetterberg H, Rosengren L, Nilsson C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chain protein levels in subtypes of frontotemporal dementia. BMC Neurol. 2013; 13(1):54. PMID: 23718879.27. Klein A, Tourville J. 101 labeled brain images and a consistent human cortical labeling protocol. Front Neurosci. 2012; 6:171. PMID: 23227001.28. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012; 62(2):774–781. PMID: 22248573.29. Collewet G, Strzelecki M, Mariette F. Influence of MRI acquisition protocols and image intensity normalization methods on texture classification. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004; 22(1):81–91. PMID: 14972397.30. Patel MB, Rodriguez JJ, Gmitro AF. Effect of gray-level re-quantization on co-occurrence based texture analysis. In : 2008 15th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing; October 12-15, 2008; San Diego, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE;p. 585–588.31. Puetz AM, Olsen R. Haralick Texture Features Expanded Into the Spectral Domain. Algorithms and Technologies for Multispectral, Hyperspectral, and Ultraspectral Imagery XII. Bellingham, WA: USA International Society for Optics and Photonics;2006. p. 623311.32. Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein IH. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 1973; SMC-3(6):610–621.33. Ortiz A, Palacio AA, Górriz JM, Ramírez J, Salas-González D. Segmentation of brain MRI using SOM-FCM-based method and 3D statistical descriptors. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013; 2013:638563. PMID: 23762192.34. Lee S, Kim KW. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Associations between texture of T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic pathologies in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2021; 28(3):735–744. PMID: 33098172.35. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983; 148(3):839–843. PMID: 6878708.36. Graham KS, Simons JS, Pratt KH, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Insights from semantic dementia on the relationship between episodic and semantic memory. Neuropsychologia. 2000; 38(3):313–324. PMID: 10678697.37. Kim EJ, Ku BD, Na DL. Semantic dementia. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2005; 4(1):10–13.38. Jun BS, Park JH. Frontotemporal dementia. Korean J Biol Psychiatry. 2016; 23(3):69–79.39. Landin-Romero R, Tan R, Hodges JR, Kumfor F. An update on semantic dementia: genetics, imaging, and pathology. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016; 8(1):52. PMID: 27915998.40. Yang J, Pan P, Song W, Shang HF. Quantitative meta-analysis of gray matter abnormalities in semantic dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012; 31(4):827–833. PMID: 22699847.41. Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, Ogar JM, Phengrasamy L, Rosen HJ, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2004; 55(3):335–346. PMID: 14991811.42. Scahill RI, Schott JM, Stevens JM, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Mapping the evolution of regional atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease: unbiased analysis of fluid-registered serial MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99(7):4703–4707. PMID: 11930016.43. Collins JA, Montal V, Hochberg D, Quimby M, Mandelli ML, Makris N, et al. Focal temporal pole atrophy and network degeneration in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2017; 140(2):457–471. PMID: 28040670.44. Rogalski E, Cobia D, Martersteck A, Rademaker A, Wieneke C, Weintraub S, et al. Asymmetry of cortical decline in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2014; 83(13):1184–1191. PMID: 25165386.45. Hodges JR, Mitchell J, Dawson K, Spillantini MG, Xuereb JH, McMonagle P, et al. Semantic dementia: demography, familial factors and survival in a consecutive series of 100 cases. Brain. 2010; 133(Pt 1):300–306. PMID: 19805492.46. Josephs KA, Hodges JR, Snowden JS, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Mann DM, et al. Neuropathological background of phenotypical variability in frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2011; 122(2):137–153. PMID: 21614463.47. Rohrer JD, Lashley T, Schott JM, Warren JE, Mead S, Isaacs AM, et al. Clinical and neuroanatomical signatures of tissue pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2011; 134(Pt 9):2565–2581. PMID: 21908872.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

- Logopenic Progressive Aphasia Revealing Positive Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Disease

- Clinical Features and Therapeutic Approaches of Frontotemporal Dementia

- Primary Progressive Aphasia and the Left Hemisphere Language Network

- Decision-making Approach in Late-onset Bilateral Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia with Coexisting Asymmetric Regional Amyloid Deposition