Anat Cell Biol.

2023 Sep;56(3):304-307. 10.5115/acb.23.037.

Innervation of pineal gland by the nervus conarii: a review of this almost forgotten structure

- Affiliations

-

- 1Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 2Department of Anatomical Sciences, St. George’s University, St. George’s, Grenada, LA, USA

- 3Department of Neurosurgery, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 4Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand

- 5Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Anatomy, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan

- 6Department of Neurology, Tulane Center for Clinical Neurosciences, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 7Department of Structural & Cellular Biology, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 8Department of Neurosurgery, Tulane Center for Clinical Neurosciences, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 9Department of Surgery, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 10Department of Neurosurgery and Ochsner Neuroscience Institute, Ochsner Health System, New Orleans, LA, USA

- 11University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

- KMID: 2546325

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5115/acb.23.037

Abstract

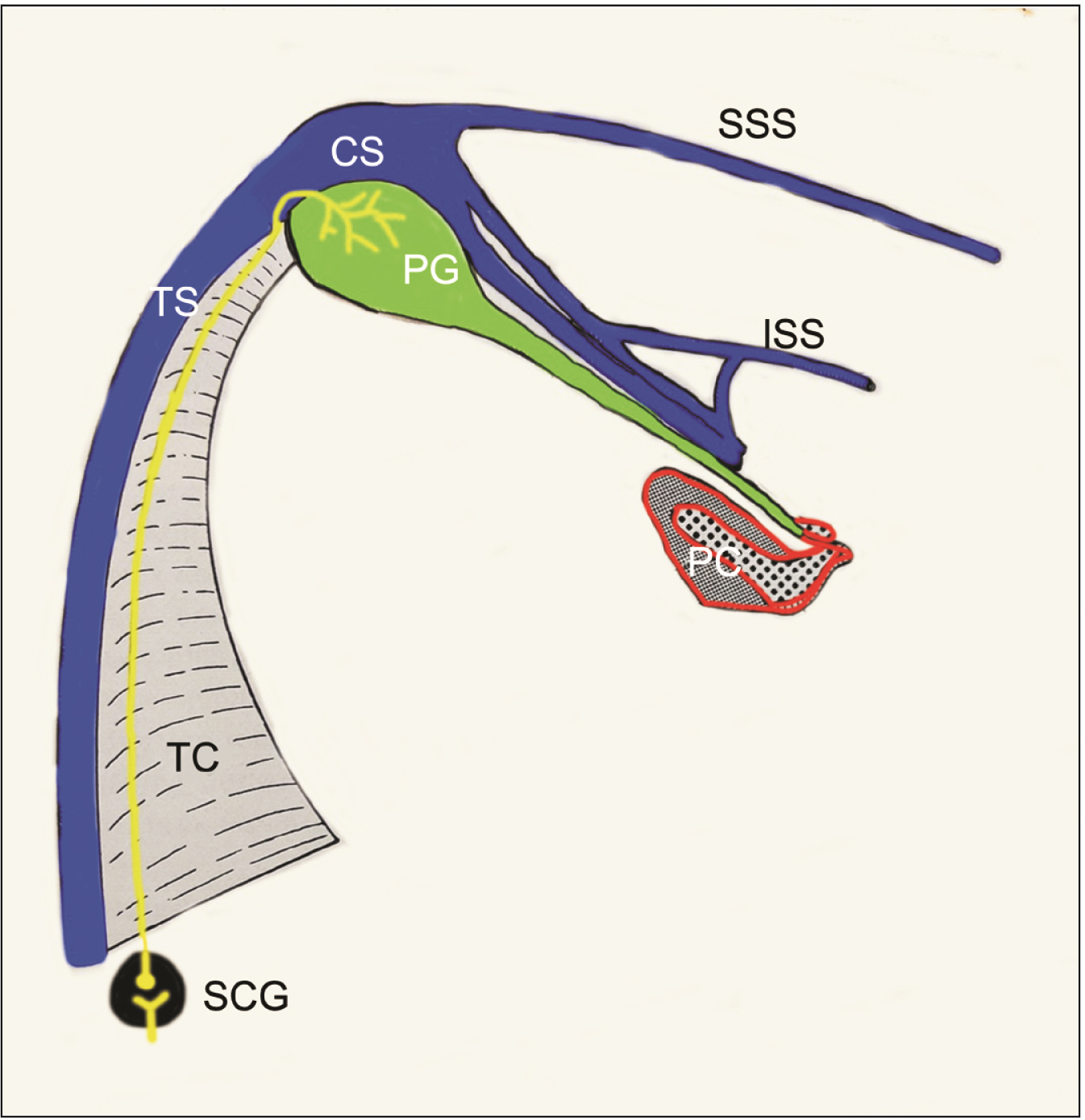

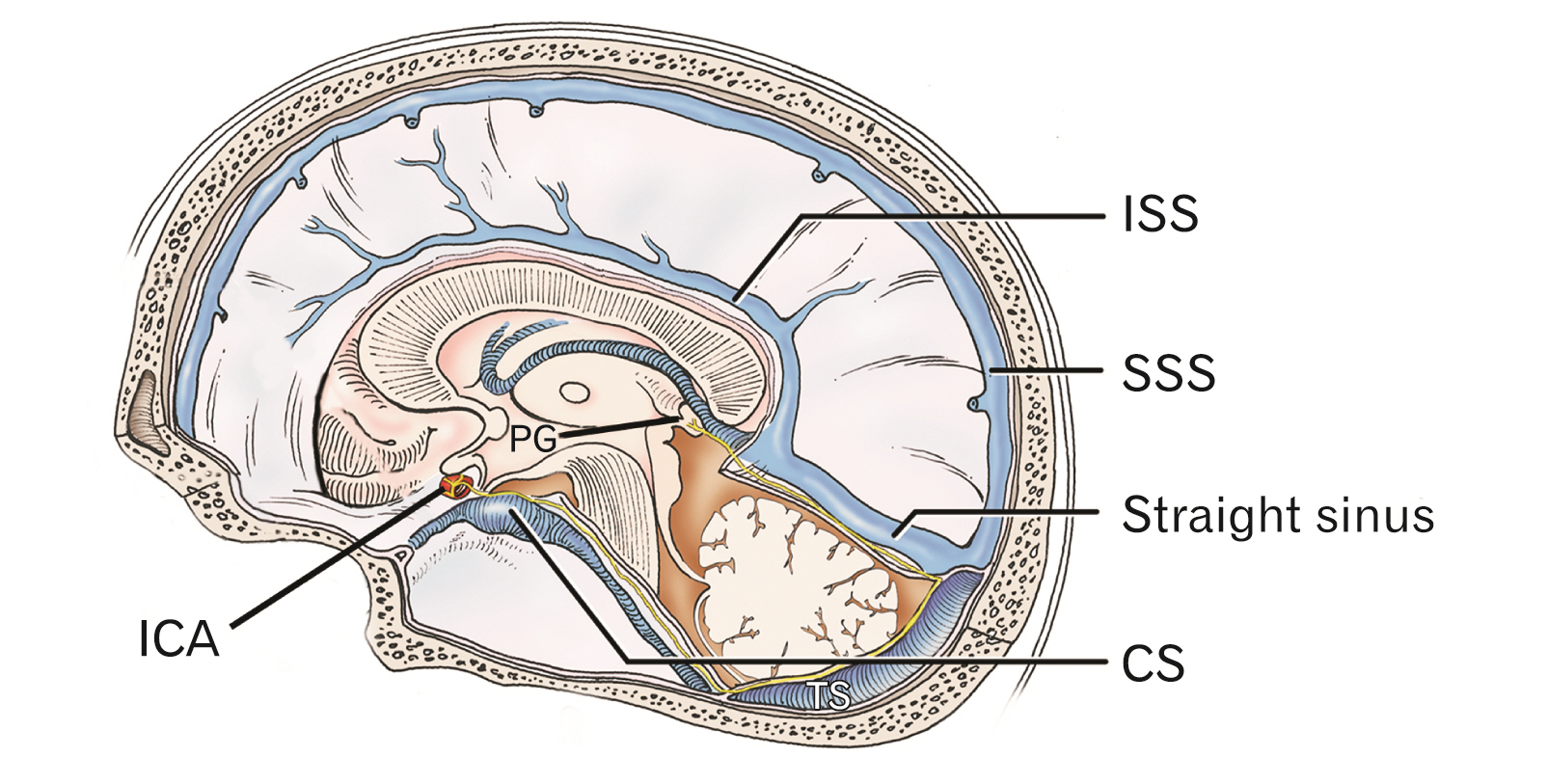

- The nervus conarii provides sympathetic nerve innervation to the pineal gland, which is thought to be the primary type of stimulus to this gland. This underreported nerve has been mostly studied in animals. One function of the nervus conarii may be to activate pinealocytes to produce melatonin. Others have also found substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide from the nervus conarii ending in the pineal gland. The following paper reviews the extant medical literature on the nervus conarii including its anatomy and potential function.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Zaccagna F, Brown FS, Allinson KSJ, Devadass A, Kapadia A, Massoud TF, Matys T. 2022; In and around the pineal gland: a neuroimaging review. Clin Radiol. 77:e107–19. DOI: 10.1016/j.crad.2021.09.020. PMID: 34774298.

Article2. Møller M, Baeres FM. 2002; The anatomy and innervation of the mammalian pineal gland. Cell Tissue Res. 309:139–50. DOI: 10.1007/s00441-002-0580-5. PMID: 12111544.

Article3. Tripathy K, Simakurthy S, Jan A. 2022. Ciliospinal reflex. StatPearls Publishing;DOI: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.4.0644.4. Haines DE, Mihailoff GA. Haines DE, Mihailoff GA, editors. 2018. The diencephalon. Fundamental neuroscience for basic and clinical applications. 5th ed. Elsevier;p. 212–24. DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-323-39632-5.00015-3.5. Rodríguez-Pérez AP. 1962; Contribution to the knowledge of the innervation of the endocrine glands. IV. First experimental results about the innervation of the epiphysis. Trab Inst Cajal Invest Biol. 54:225–36. Spanish.6. Kappers JA, Schadé JP. 1965. Structure and function of the epiphysis cerebri. Elsevier;DOI: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)x6101-1.7. Mollgaard K, Moller M. 1973; On the innervation of the human fetal pineal gland. Brain Res. 52:428–32. DOI: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90686-0. PMID: 4700723.

Article8. Kappers JA. 1960; The development, topographical relations and innervation of the epiphysis cerebri in the albino rat. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 52:163–215. DOI: 10.1007/BF00338980. PMID: 13751359.

Article9. Bowers CW, Dahm LM, Zigmond RE. 1984; The number and distribution of sympathetic neurons that innervate the rat pineal gland. Neuroscience. 13:87–96. DOI: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90261-6. PMID: 6493487.

Article10. Kenny GC. 1961; The "nervus conarii" of the monkey. (An experimental study). J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 20:563–70. DOI: 10.1097/00005072-196120040-00007. PMID: 13830926.11. Pastori G. 1930; A hitherto undescribed sympathetic ganglion and its relations to the conari nerve and the great vein of Galen. Neurol Psychiat. 123:81–90. German. DOI: 10.1007/BF02865496.12. Macchi MM, Bruce JN. 2004; Human pineal physiology and functional significance of melatonin. Front Neuroendocrinol. 25:177–95. DOI: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.08.001. PMID: 15589268.

Article13. Dafny N. 1980; Two photic pathways contribute to pineal evoked responses. Life Sci. 26:737–42. DOI: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90264-7. PMID: 7366343.

Article14. Quay WB. 1971; Effects of cutting nervi conarii and tentorium cerebelli on pineal composition and activity shifting following reversal of photoperiod. Physiol Behav. 6:681–8. DOI: 10.1016/0031-9384(71)90254-X. PMID: 4337176.

Article15. Machado ABM. 1971; Electron microscopy of developing sympathetic fibres in the rat pineal body the formation of granular vesicles. Prog Brain Res. 34:171–85. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63963-1.

Article16. Wetterberg L. 1979; Clinical importance of melatonin. Prog Brain Res. 52:539–47. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62962-3. PMID: 549099.

Article17. Shafii M, Shafii SL. 1990. Biological rhythms, mood disorders, light therapy, and the pineal gland. American Psychiatric Press;DOI: 10.5860/choice.28-3881.18. Lumsden SC, Clarkson AN, Cakmak YO. 2020; Neuromodulation of the pineal gland via electrical stimulation of its sympathetic innervation pathway. Front Neurosci. 14:264. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00264. PMID: 32300290. PMCID: PMC7145358. PMID: 24c45fde11894eb3b8d4841eeca5b021.

Article19. Klein DC, Coon SL, Roseboom PH, Weller JL, Bernard M, Gastel JA, Zatz M, Iuvone PM, Rodriguez IR, Bégay V, Falcón J, Cahill GM, Cassone VM, Baler R. 1997; The melatonin rhythm-generating enzyme: molecular regulation of serotonin N-acetyltransferase in the pineal gland. Recent Prog Horm Res. 52:307–57. discussion 357–8. PMID: 9238858.20. Bertler A, Falck B, Owman C. 1964; Studies on 5-hydroxytryptamine stores in pineal gland of rat. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 220(Suppl 239):1–18. DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb04118.x. PMID: 14298286.

Article21. Bulc M, Lewczuk B. 2019; Innervation of the pineal gland in the Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus) by nerve fibres immunoreactive to substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 78:695–702. DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2019.0024. PMID: 30835341.

Article