Int J Stem Cells.

2023 Aug;16(3):293-303. 10.15283/ijsc22168.

Notch Is Not Involved in Physioxia-Mediated Stem Cell Maintenance in Midbrain Neural Stem Cells

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Department of Neurology, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

- 2Institute of Systems, Molecular and Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

- 3Department of Neurology, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

- 4Molecular Endocrinology, Medical Clinic III, University Clinic Dresden, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany

- 5Translational Neurodegeneration Section Translational Neurodegeneration Section “Albrecht Kossel”, Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Rostock, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

- 6Deutsches Zentrum für Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen (DZNE) Rostock/Greifswald, Rostock, Germany

- KMID: 2545229

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc22168

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

The physiological oxygen tension in fetal brains (∼3%, physioxia) is beneficial for the maintenance of neural stem cells (NSCs). Sensitivity to oxygen varies between NSCs from different fetal brain regions, with midbrain NSCs showing selective susceptibility. Data on Hif-1α/Notch regulatory interactions as well as our observations that Hif-1α and oxygen affect midbrain NSCs survival and proliferation prompted our investigations on involvement of Notch signalling in physioxia-dependent midbrain NSCs performance.

Methods and Results

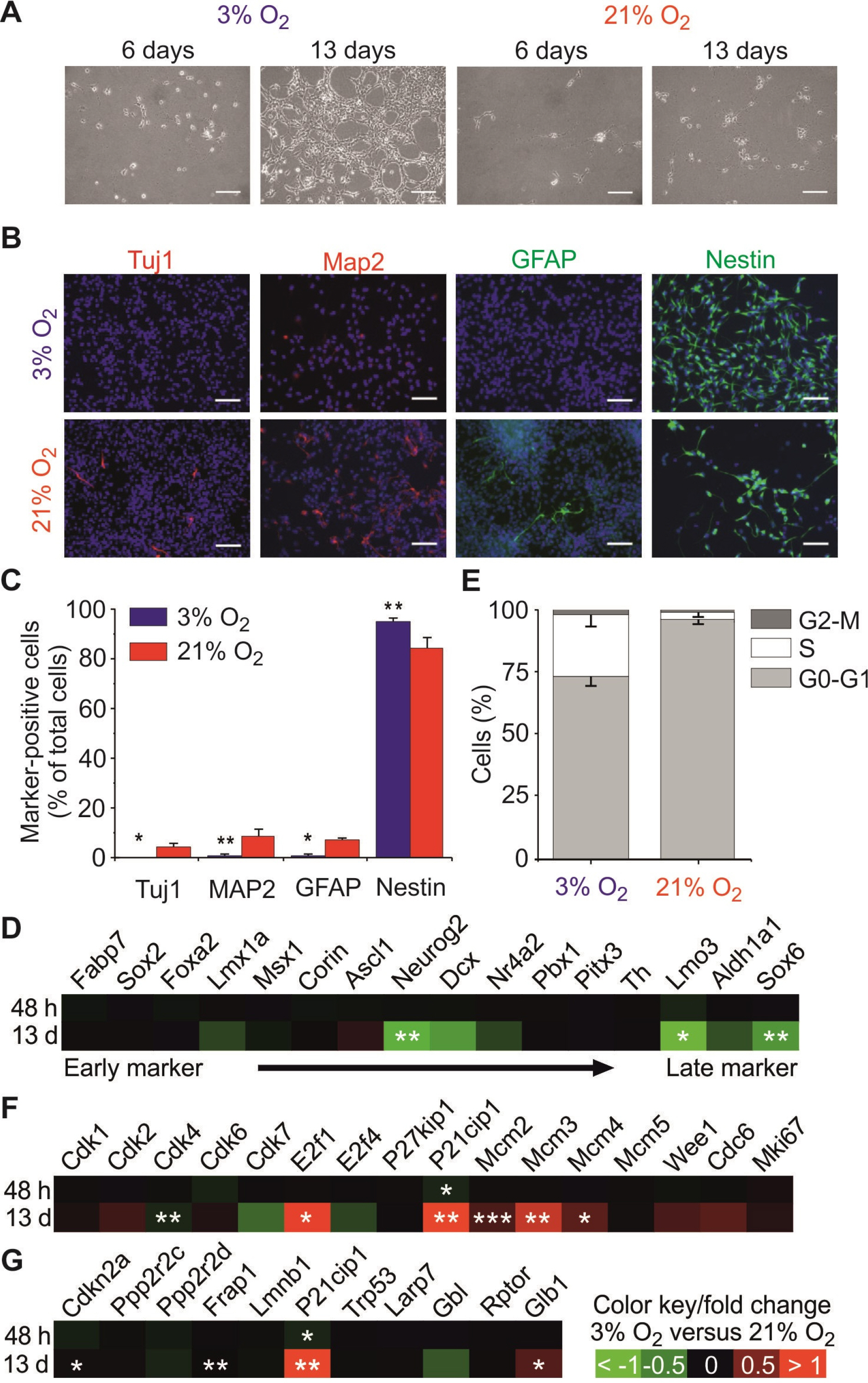

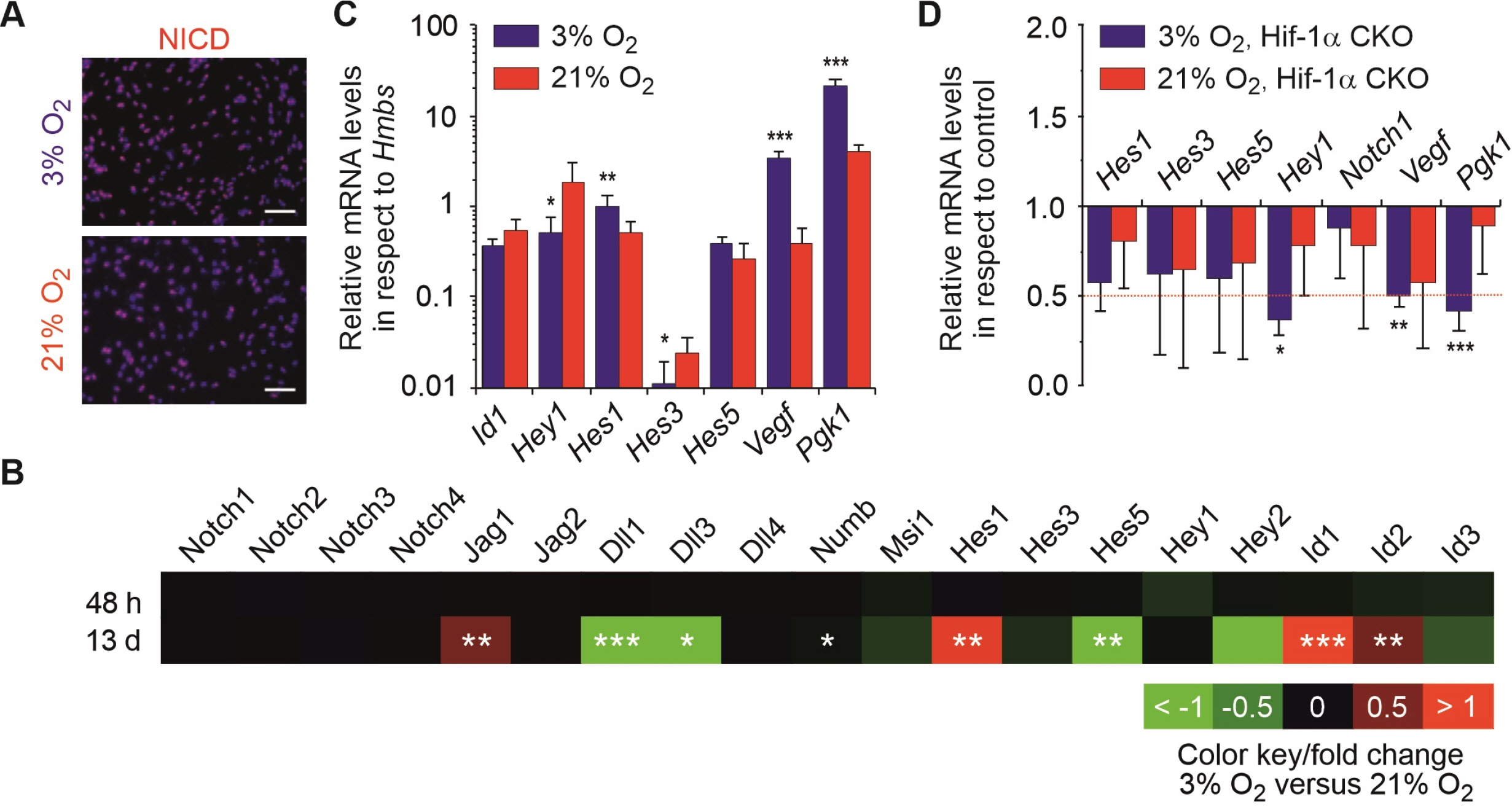

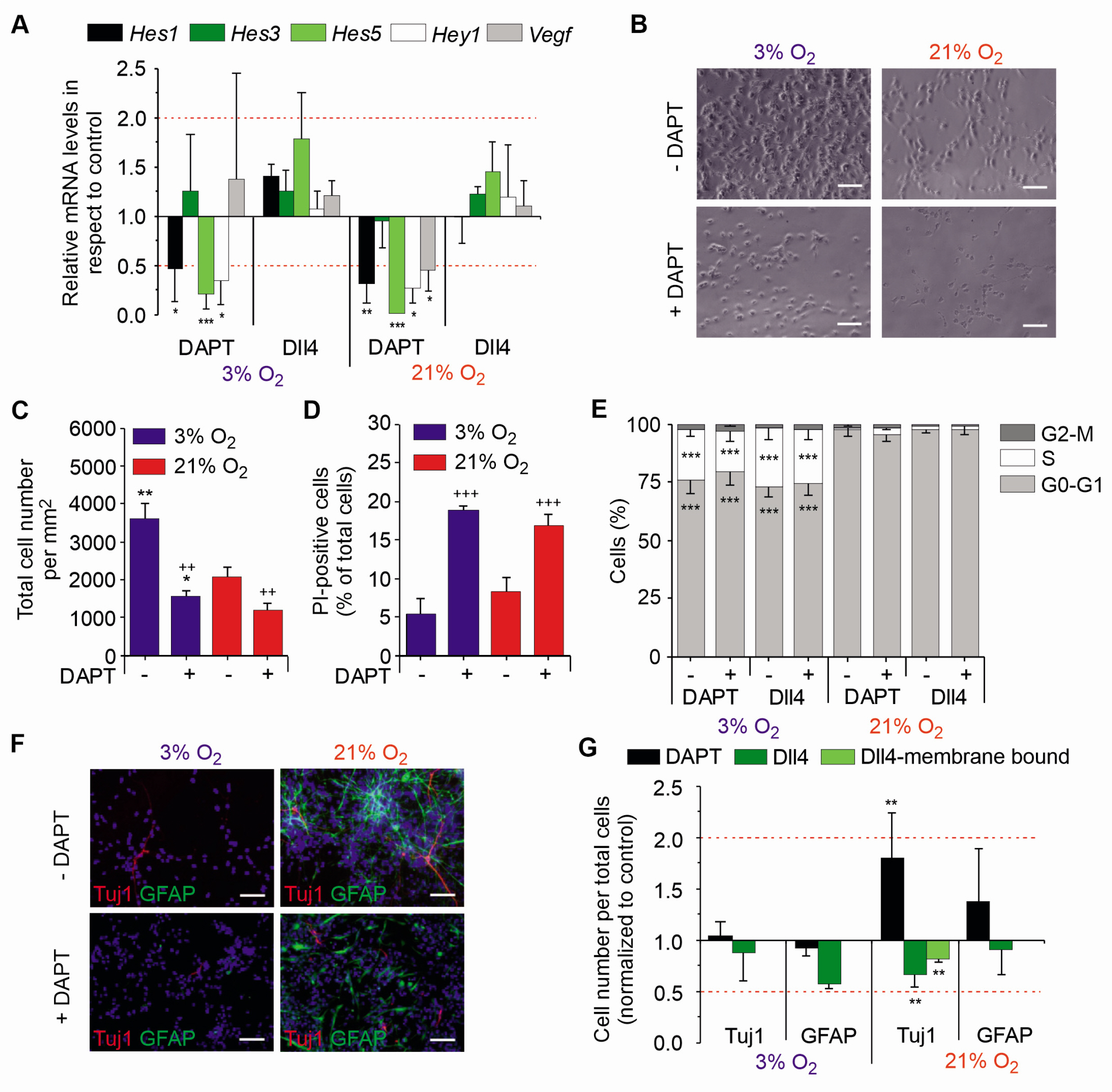

Here we found that physioxia (3% O2 ) compared to normoxia (21% O 2 ) increased proliferation, maintained stemness by suppression of spontaneous differentiation and supported cell cycle progression. Microarray and qRT-PCR analyses identified significant changes of Notch related genes in midbrain NSCs after long-term (13 days), but not after short-term physioxia (48 hours). Consistently, inhibition of Notch signalling with DAPT increased, but its stimulation with Dll4 decreased spontaneous differentiation into neurons solely under normoxic but not under physioxic conditions.

Conclusions

Notch signalling does not influence the fate decision of midbrain NSCs cultured in vitro in physioxia, where other factors like Hif-1α might be involved. Our findings on how physioxia effects in midbrain NSCs are transduced by alternative signalling might, at least in part, explain their selective susceptibility to oxygen.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Storch A, Paul G, Csete M, Boehm BO, Carvey PM, Kupsch A, Schwarz J. 2001; Long-term proliferation and dopaminergic differentiation of human mesencephalic neural precursor cells. Exp Neurol. 170:317–325. DOI: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7706. PMID: 11476598.

Article2. Studer L, Csete M, Lee SH, Kabbani N, Walikonis J, Wold B, McKay R. 2000; Enhanced proliferation, survival, and dopaminergic differentiation of CNS precursors in lowered oxygen. J Neurosci. 20:7377–7383. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07377.2000. PMID: 11007896. PMCID: PMC6772777.

Article3. Milosevic J, Maisel M, Wegner F, Leuchtenberger J, Wenger RH, Gerlach M, Storch A, Schwarz J. 2007; Lack of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha impairs midbrain neural precursor cells involving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. J Neurosci. 27:412–421. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2482-06.2007. PMID: 17215402. PMCID: PMC6672078.

Article4. Silver I, Erecińska M. 1998; Oxygen and ion concentrations in normoxic and hypoxic brain cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 454:7–16. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4863-8_2. PMID: 9889871.

Article5. Semenza GL, Wang GL. 1992; A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 12:5447–5454. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.12.12.5447. PMID: 1448077. PMCID: PMC360482.

Article6. Semenza GL. 1998; Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: master regulator of O2 homeostasis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 8:588–594. DOI: 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80016-6. PMID: 9794818.

Article7. Tomita S, Ueno M, Sakamoto M, Kitahama Y, Ueki M, Maekawa N, Sakamoto H, Gassmann M, Kageyama R, Ueda N, Gonzalez FJ, Takahama Y. 2003; Defective brain development in mice lacking the Hif-1 alpha gene in neural cells. Mol Cell Biol. 23:6739–6749. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6739-6749.2003. PMID: 12972594. PMCID: PMC193947.

Article8. Lange C, Turrero Garcia M, Decimo I, Bifari F, Eelen G, Quaegebeur A, Boon R, Zhao H, Boeckx B, Chang J, Wu C, Le Noble F, Lambrechts D, Dewerchin M, Kuo CJ, Huttner WB, Carmeliet P. 2016; Relief of hypoxia by angiogenesis promotes neural stem cell differentiation by targeting glycolysis. EMBO J. 35:924–941. DOI: 10.15252/embj.201592372. PMID: 26856890. PMCID: PMC5207321.

Article9. Androutsellis-Theotokis A, Leker RR, Soldner F, Hoeppner DJ, Ravin R, Poser SW, Rueger MA, Bae SK, Kittappa R, McKay RD. 2006; Notch signalling regulates stem cell numbers in vitro and in vivo. Nature. 442:823–826. DOI: 10.1038/nature04940. PMID: 16799564.

Article10. Yoon K, Gaiano N. 2005; Notch signaling in the mammalian central nervous system: insights from mouse mutants. Nat Neurosci. 8:709–715. DOI: 10.1038/nn1475. PMID: 15917835.

Article11. Marinopoulou E, Biga V, Sabherwal N, Miller A, Desai J, Adamson AD, Papalopulu N. 2021; HES1 protein oscillations are necessary for neural stem cells to exit from quiescence. iScience. 24:103198. DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103198. PMID: 34703994. PMCID: PMC8524149.

Article12. Ochi S, Imaizumi Y, Shimojo H, Miyachi H, Kageyama R. 2020; Oscillatory expression of Hes1 regulates cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation in the embryonic brain. Development. 147:dev182204. DOI: 10.1242/dev.182204. PMID: 32094111.

Article13. Ishibashi M, Moriyoshi K, Sasai Y, Shiota K, Nakanishi S, Kageyama R. 1994; Persistent expression of helix-loop-helix factor HES-1 prevents mammalian neural differentiation in the central nervous system. EMBO J. 13:1799–1805. DOI: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06448.x. PMID: 7909512. PMCID: PMC395019.

Article14. Louvi A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. 2006; Notch signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 7:93–102. DOI: 10.1038/nrn1847. PMID: 16429119.

Article15. Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, Ruas JL, Poellinger L, Lendahl U, Bondesson M. 2005; Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 9:617–628. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. PMID: 16256737.

Article16. Pistollato F, Rampazzo E, Persano L, Abbadi S, Frasson C, Denaro L, D'Avella D, Panchision DM, Della Puppa A, Scienza R, Basso G. 2010; Interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and Notch signaling regulates medulloblastoma precursor proliferation and fate. Stem Cells. 28:1918–1929. DOI: 10.1002/stem.518. PMID: 20827750. PMCID: PMC3474900.

Article17. Večeřa J, Procházková J, Šumberová V, Pánská V, Paculová H, Lánová MK, Mašek J, Bohačiaková D, Andersson ER, Pacherník J. 2020; Hypoxia/Hif1α prevents premature neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells through the activation of Hes1. Stem Cell Res. 45:101770. DOI: 10.1016/j.scr.2020.101770. PMID: 32276221.

Article18. Braunschweig L, Lanto J, Meyer AK, Markert F, Storch A. 2022; Serial gene expression profiling of neural stem cells shows transcriptome switch by long-term physioxia from metabolic adaption to cell signaling profile. Stem Cells Int. 2022:6718640. DOI: 10.1155/2022/6718640. PMID: 36411871. PMCID: PMC9675612. PMID: 13a478f2d30148e2bc1f77cdc38d6267.

Article19. Braunschweig L, Meyer AK, Wagenführ L, Storch A. 2015; Oxygen regulates proliferation of neural stem cells through Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 67:84–92. DOI: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.06.006. PMID: 26079803.

Article20. Meyer AK, Jarosch A, Schurig K, Nuesslein I, Kißenkötter S, Storch A. 2012; Fetal mouse mesencephalic NPCs generate dopaminergic neurons from post-mitotic precursors and maintain long-term neural but not dopaminergic potential in vitro. Brain Res. 1474:8–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.07.034. PMID: 22842082.

Article21. Suzuki M, Yamamoto M, Sugimoto A, Nakamura S, Motoda R, Orita K. 2006; Delta-4 expression on a stromal cell line is augmented by interleukin-6 via STAT3 activation. Exp Hematol. 34:1143–1150. DOI: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.027. PMID: 16939807.

Article22. Ásgrímsdóttir ES, Arenas E. 2020; Midbrain dopaminergic neuron development at the single cell level: In vivo and in stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:463. DOI: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00463. PMID: 32733875. PMCID: PMC7357704. PMID: 5af89fe2e21e4997b109797a13a8d84e.

Article23. Calegari F, Huttner WB. 2003; An inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases that lengthens, but does not arrest, neuroepithelial cell cycle induces premature neurogenesis. J Cell Sci. 116(Pt 24):4947–4955. DOI: 10.1242/jcs.00825. PMID: 14625388.

Article24. Hartmann C, Herling L, Hartmann A, Köckritz V, Fuellen G, Walter M, Hermann A. 2023; Systematic estimation of biological age of in vitro cell culture systems by an age-associated marker panel. Front Aging. 4:1129107. DOI: 10.3389/fragi.2023.1129107. PMID: 36873743. PMCID: PMC9975507. PMID: 25e3139385b042abb8c848f5069953bf.

Article25. Borghese L, Dolezalova D, Opitz T, Haupt S, Leinhaas A, Steinfarz B, Koch P, Edenhofer F, Hampl A, Brüstle O. 2010; Inhibition of notch signaling in human embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells delays G1/S phase transition and accelerates neuronal differentiation in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells. 28:955–964. DOI: 10.1002/stem.408. PMID: 20235098.

Article26. Kaise T, Kageyama R. 2021; Hes1 oscillation frequency correlates with activation of neural stem cells. Gene Expr Patterns. 40:119170. DOI: 10.1016/j.gep.2021.119170. PMID: 33675998.

Article27. Blackwood CA. 2019; Jagged1 is essential for radial glial maintenance in the cortical proliferative zone. Neuroscience. 413:230–238. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.05.062. PMID: 31202705. PMCID: PMC7491705.

Article28. Kageyama R, Niwa Y, Shimojo H, Kobayashi T, Ohtsuka T. 2010; Ultradian oscillations in Notch signaling regulate dynamic biological events. Curr Top Dev Biol. 92:311–331. DOI: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92010-3. PMID: 20816400.

Article29. Niola F, Zhao X, Singh D, Castano A, Sullivan R, Lauria M, Nam HS, Zhuang Y, Benezra R, Di Bernardo D, Iavarone A, Lasorella A. 2012; Id proteins synchronize stemness and anchorage to the niche of neural stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 14:477–487. DOI: 10.1038/ncb2490. PMID: 22522171. PMCID: PMC3635493.

Article30. Boareto M, Iber D, Taylor V. 2017; Differential interactions between Notch and ID factors control neurogenesis by modulating Hes factor autoregulation. Development. 144:3465–3474. DOI: 10.1242/dev.152520. PMID: 28974640. PMCID: PMC5665482.

Article31. Nelson BR, Hodge RD, Daza RA, Tripathi PP, Arnold SJ, Millen KJ, Hevner RF. 2020; Intermediate progenitors support migration of neural stem cells into dentate gyrus outer neurogenic niches. Elife. 9:e53777. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.53777. PMID: 32238264. PMCID: PMC7159924. PMID: f6a9cc73f49c42e5945cb98f7ba78864.

Article32. Chin MT, Maemura K, Fukumoto S, Jain MK, Layne MD, Watanabe M, Hsieh CM, Lee ME. 2000; Cardiovascular basic helix loop helix factor 1, a novel transcriptional repressor expressed preferentially in the developing and adult cardiovascular system. J Biol Chem. 275:6381–6387. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6381. PMID: 10692439.

Article33. Park DM, Jung J, Masjkur J, Makrogkikas S, Ebermann D, Saha S, Rogliano R, Paolillo N, Pacioni S, McKay RD, Poser S, Androutsellis-Theotokis A. 2013; Hes3 regulates cell number in cultures from glioblastoma multiforme with stem cell characteristics. Sci Rep. 3:1095. DOI: 10.1038/srep01095. PMID: 23393614. PMCID: PMC3566603.

Article34. Nishimura M, Isaka F, Ishibashi M, Tomita K, Tsuda H, Nakanishi S, Kageyama R. 1998; Structure, chromosomal locus, and promoter of mouse Hes2 gene, a homologue of Droso-phila hairy and Enhancer of split. Genomics. 49:69–75. DOI: 10.1006/geno.1998.5213. PMID: 9570950.

Article35. Lobov IB, Renard RA, Papadopoulos N, Gale NW, Thur-ston G, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ. 2007; Delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) is induced by VEGF as a negative regulator of angiogenic sprouting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:3219–3224. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0611206104. PMID: 17296940. PMCID: PMC1805530.

Article36. Hitoshi S, Alexson T, Tropepe V, Donoviel D, Elia AJ, Nye JS, Conlon RA, Mak TW, Bernstein A, van der Kooy D. 2002; Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 16:846–858. DOI: 10.1101/gad.975202. PMID: 11937492. PMCID: PMC186324.

Article37. Pistollato F, Rampazzo E, Abbadi S, Della Puppa A, Scienza R, D'Avella D, Denaro L, Te Kronnie G, Panchision DM, Basso G. 2009; Molecular mechanisms of HIF-1alpha modulation induced by oxygen tension and BMP2 in glioblastoma derived cells. PLoS One. 4:e6206. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006206. PMID: 19587783. PMCID: PMC2702690. PMID: f8b53d466b8b4b6ab0d6100e404c9e8f.38. Gaiano N, Fishell G. 2002; The role of notch in promoting glial and neural stem cell fates. Annu Rev Neurosci. 25:471–490. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.030702.130823. PMID: 12052917.

Article39. Kaufmann MR, Barth S, Konietzko U, Wu B, Egger S, Kunze R, Marti HH, Hick M, Müller U, Camenisch G, Wenger RH. 2013; Dysregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor by presenilin/γ-secretase loss-of-function mutations. J Neuro-sci. 33:1915–1926. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3402-12.2013. PMID: 23365231. PMCID: PMC6619134.

Article40. Mukherjee T, Kim WS, Mandal L, Banerjee U. 2011; Interaction between Notch and Hif-alpha in development and survival of Drosophila blood cells. Science. 332:1210–1213. DOI: 10.1126/science.1199643. PMID: 21636775. PMCID: PMC4412745.

Article41. Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VS Jr. 1995; The cell cycle of the pseudostratified ventricular epithelium of the embryonic murine cerebral wall. J Neurosci. 15:6046–6057. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06046.1995. PMID: 7666188. PMCID: PMC6577667.

Article42. Semenza GL. 2011; Hypoxia. Cross talk between oxygen sensing and the cell cycle machinery. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 301:C550–C552. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00176.2011. PMID: 21677261. PMCID: PMC3174572.

Article43. Bertoli C, Skotheim JM, de Bruin RA. 2013; Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14:518–528. DOI: 10.1038/nrm3629. PMID: 23877564. PMCID: PMC4569015.

Article44. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kro-emer G. 2013; The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 153:1194–1217. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. PMID: 23746838. PMCID: PMC3836174.

Article