Ewha Med J.

2023 Jul;46(3):e7. 10.12771/emj.2023.e7.

A Proactive Testing Strategy to COVID-19 for Reopening University Campus during Omicron Wave in Korea: Ewha Safe Campus (ESC) Project

- Affiliations

-

- 1School of Biomedical Convergence Engineering, College of Information and Biomedical Engineering, Pusan National University, Yangsan, Korea

- 2Department of Environmental Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Preventive Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Graduate Program in System Health Science and Engineering, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Clinical Research Institute, Seegene Medical Foundation, Seoul, Korea

- 6Molecular Diagnosis Center, Seegene Medical Foundation, Seoul, Korea

- 7Department of Marketing, Seegene Medical Foundation, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 9Ewha Education & Research Center for Infection, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea

- 10Ewha Medical Research Institute, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2545172

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2023.e7

Abstract

Objectives

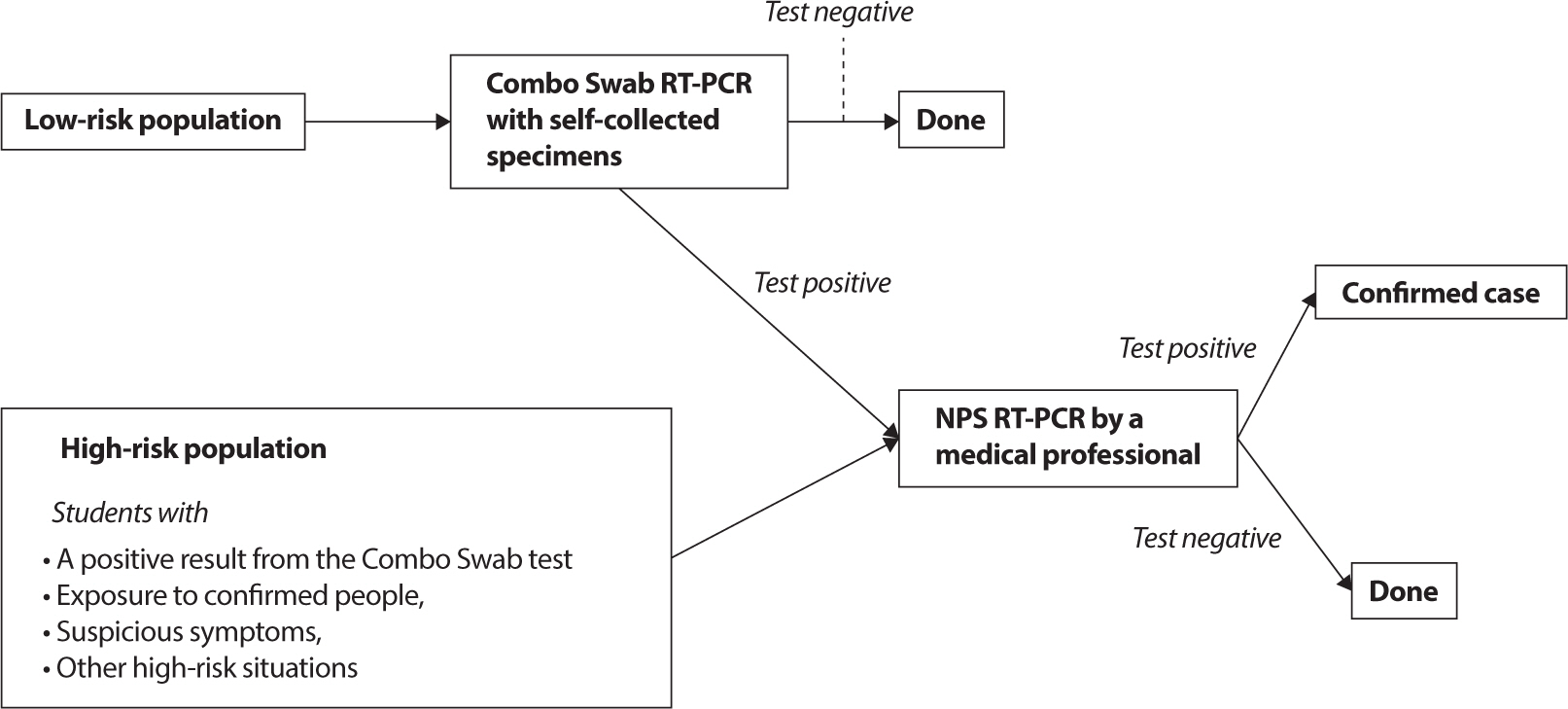

Ewha Womans University launched an on-campus Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) response system called Ewha Safety Campus (ESC) Project in collaboration with the Seegene Inc. RTPCR diagnostic tests for COVID-19 were proactively provided to the participants. This study examines the effectiveness of the on-campus testing strategy in controlling the reproduction number (Rt ) and identifying student groups vulnerable to infection.

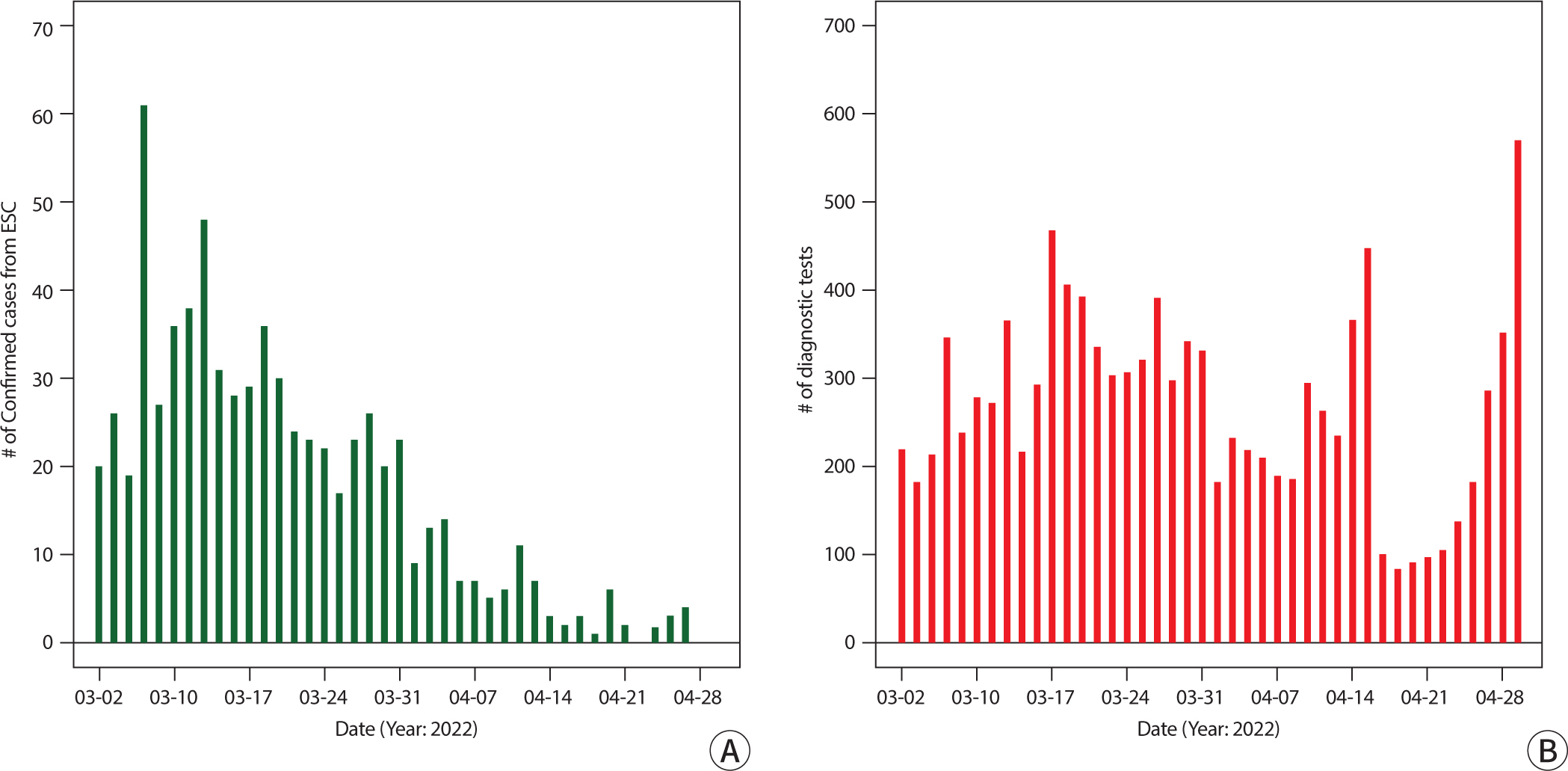

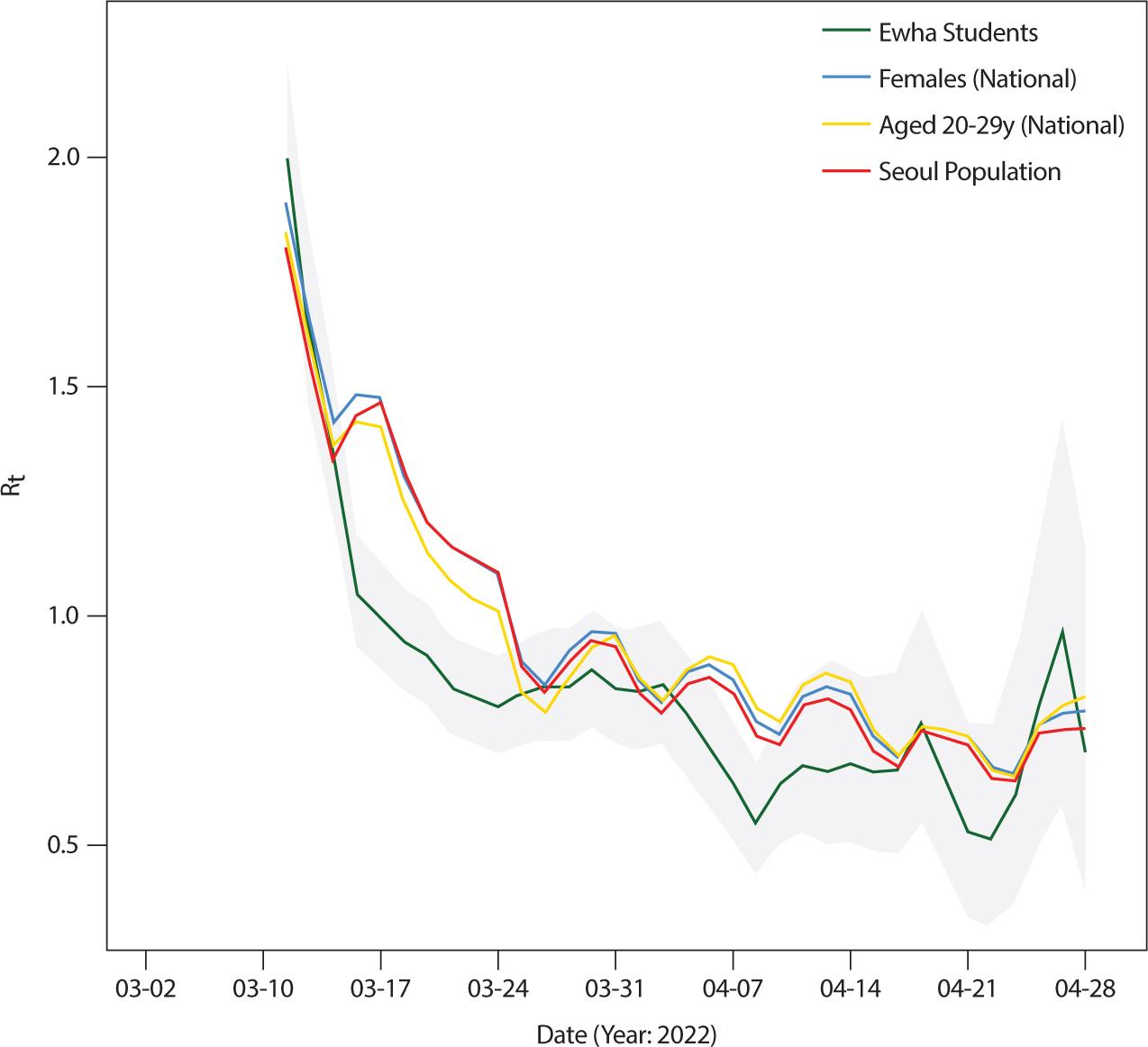

Methods

The ESC project was launched on March 2, 2022, with a pilot period from Feb 22 to March 1, 2022—the peak of the Omicron variant wave. We collected daily data on the RT-PCR test results of the students of Ewha Womans University from Mar 2 to Apr 30, 2022. We daily calculated Rt and compared it with that of the general population of Korea (women, people aged 20–29 years, and Seoul residents). We also examined the students vulnerable to the infection based on the group-specific Rt and positivity rate.

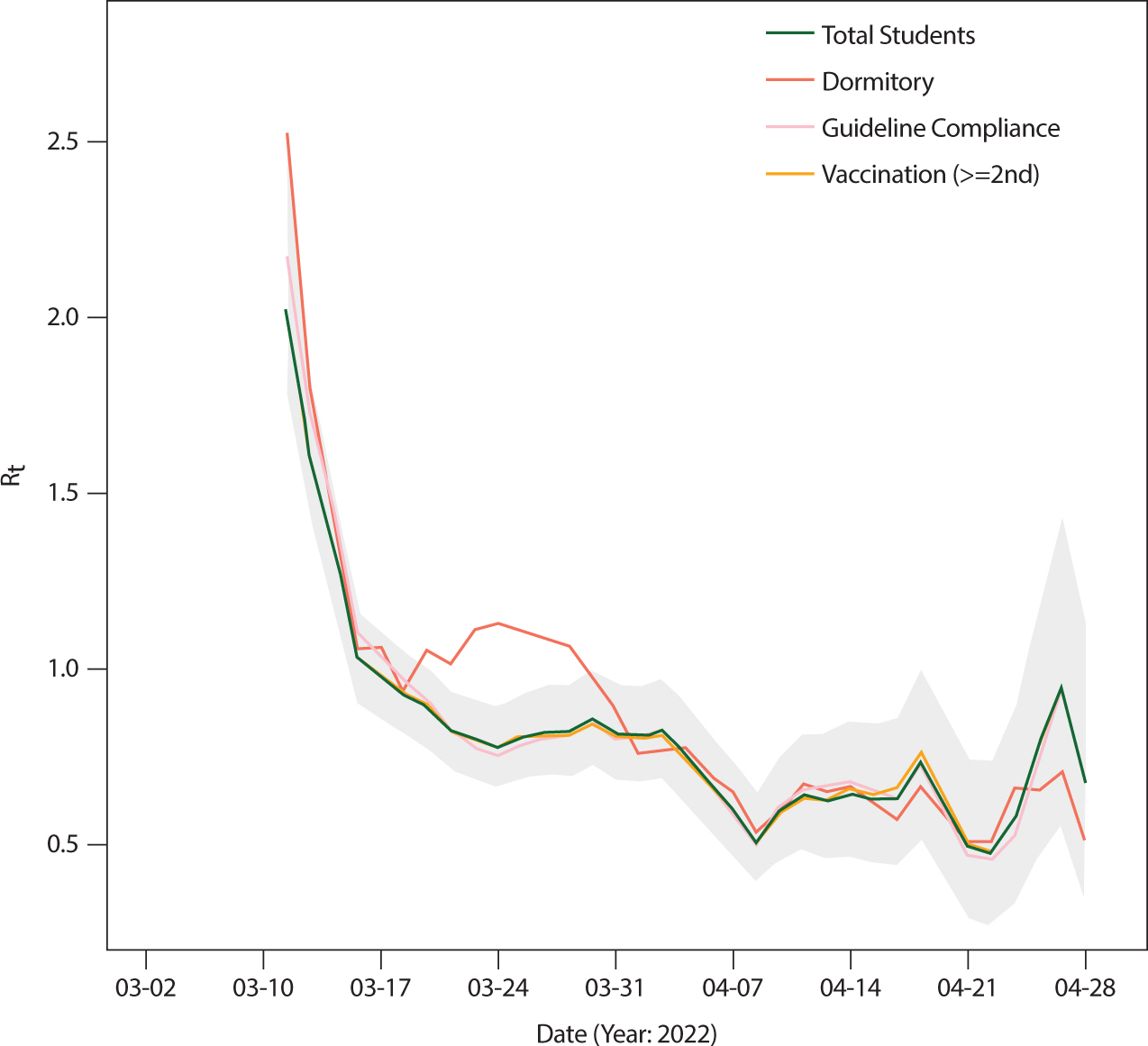

Results

A lower Rt was observed about 2 weeks after the implementation of the ESC Project than that of the general population. The lower Rt persisted during the entire study period. Dormitory residents had a higher Rt . The positivity rate was higher in students who did not comply with quarantine guidelines and did not receive the second dose of the vaccine.

Conclusion

The study provides scientific evidence for the effectiveness of the on-campus testing strategy and different infection vulnerabilities of students, depending on dormitory residence, compliance with the quarantine guidelines, and vaccination.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus dashboard 2022 [Internet]. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization;c2022. [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: http://covid19.who.int.2. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. National status of COVID-19 and vaccination (As of May 1st) [Internet]. Cheongju (KR): Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;c2022. [cited 2022 Aug 13]. Available from: https://ncov.kdca.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?brdId=3&brdGubun=31&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=6603&contSeq=6603&board_id=312&gubun=BDJ.3. Chang CN, Chien HY, Malagon-Palacios L. College reopening and community spread of COVID-19 in the United States. Public Health. 2022; 204:70–75. DOI: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.001. PMID: 35176623. PMCID: PMC8747949.

Article4. Andersen MS, Bento AI, Basu A, Marsicano CR, Simon KI. College openings in the United States increase mobility and COVID-19 incidence. PLoS One. 2022; 17(8):e0272820. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272820. PMID: 36037207. PMCID: PMC9423614.

Article5. Cheng SY, Jason Wang C, Shen ACT, Chang SC. How to safely reopen colleges and universities during COVID-19: experiences from Taiwan. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173((8)):638–641. DOI: 10.7326/M20-2927. PMID: 32614638. PMCID: PMC7339040.

Article6. Pollock BH, Marm Kilpatrick A, Eisenman DP, Elton KL, Rutherford GW, Boden-Albala BM, et al. Safe reopening of college campuses during COVID-19: the University of California experience in fall 2020. PLoS One. 2021; 16(11):e0258738. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258738. PMID: 34735480. PMCID: PMC8568179.

Article7. Ministry of Education. 2022 1st Semester educational operation plans against Omicron variant. Sejong: Ministry of Education;2022.8. Jung-Choi K, Sung N, Lee SH, Chang M, Choi HJ, Kim CJ, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic response system at university level: the case of safe campus model at Ewha Womans University. Ewha Med J. 2022; 45(4):e18. DOI: 10.12771/emj.2022.e18.9. Lim HJ, Baek YH, Park MY, Yang JH, Kim MJ, Sung N, et al. Performance analysis of self-collected nasal and oral swabs for detection of SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(10):2279. DOI: 10.3390/diagnostics12102279. PMID: 36291968. PMCID: PMC9600397.

Article10. Hong KH, Lee SW, Kim TS, Huh HJ, Lee J, Kim SY, et al. Guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2020; 40((5)):351–360. DOI: 10.3343/alm.2020.40.5.351. PMID: 32237288. PMCID: PMC7169629.

Article11. Cori A, Ferguson NM, Fraser C, Cauchemez S. A new framework and software to estimate time-varying reproduction numbers during epidemics. Am J Epidemiol. 2013; 178((9)):1505–1512. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwt133. PMID: 24043437. PMCID: PMC3816335.

Article12. Lee W, Hwang SS, Song I, Park C, Kim H, Song IK, et al. COVID-19 in South Korea: epidemiological and spatiotemporal patterns of the spread and the role of aggressive diagnostic tests in the early phase. Int J Epidemiol. 2020; 49((4)):1106–1116. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyaa119. PMID: 32754756. PMCID: PMC7454567.

Article13. Thompson RN, Stockwin JE, van Gaalen RD, Polonsky JA, Kamvar ZN, Demarsh PA, et al. Improved inference of time-varying reproduction numbers during infectious disease outbreaks. Epidemics. 2019; 29:100356. DOI: 10.1016/j.epidem.2019.100356. PMID: 31624039. PMCID: PMC7105007.

Article14. Kim D, Ali ST, Kim S, Jo J, Lim JS, Lee S, et al. Estimation of serial interval and reproduction number to quantify the transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in South Korea. Viruses. 2022; 14(3):533. DOI: 10.3390/v14030533. PMID: 35336939. PMCID: PMC8948735.

Article15. Lee W, Kim H, Choi HM, Heo S, Fong KC, Yang J, et al. Urban environments and COVID-19 in three eastern states of the United States. Sci Total Environ. 2021; 779:146334. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146334. PMID: 33744577. PMCID: PMC7952127.

Article16. Peck KR. Early diagnosis and rapid isolation: response to COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020; 26((7)):805–807. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.025. PMID: 32344168. PMCID: PMC7182747.

Article17. Van Pelt A, Glick HA, Yang W, Rubin D, Feldman M, Kimmel SE. Evaluation of COVID-19 testing strategies for repopulating college and university campuses: a decision tree analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2021; 68((1)):28–34. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.038. PMID: 33153883. PMCID: PMC7606071.

Article18. David Paltiel A, Zheng A, Walensky RP. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening strategies to permit the safe reopening of college campuses in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(7):e2016818. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16818. PMID: 32735339. PMCID: PMC7395236.

Article19. Schultes O, Clarke V, David Paltiel A, Cartter M, Sosa L, Crawford FW. COVID-19 testing and case rates and social contact among residential college students in Connecticut during the 2020-2021 academic year. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(12):e2140602. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40602. PMID: 34940864. PMCID: PMC8703252.

Article20. Gajda M, Kowalska M, Zejda JE. Impact of two different recruitment procedures (random vs. volunteer selection) on the results of seroepidemiological tudy (SARS-CoV-2). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9928. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18189928. PMID: 34574850. PMCID: PMC8466492.

Article21. Griffith GJ, Morris TT, Tudball MJ, Herbert A, Mancano G, Pike L, et al. Collider bias undermines our understanding of COVID-19 disease risk and severity. Nat Commun. 2020; 11(1):5749. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-19478-2. PMID: 33184277. PMCID: PMC7665028.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The COVID-19 Pandemic Response System at University Level: The Case of Safe Campus Model at Ewha Womans University

- Comparison of the Clinical and Laboratory Features of COVID-19 in Children During All Waves of the Epidemic: A Single Center Retrospective Study

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 Cases at Universities and Colleges in Seoul Metropolitan Area

- Seizure Incidence among Children Hospitalized with COVID-19 during the Omicron Wave

- The Impact of Omicron Wave on Pediatric Febrile Seizure