Korean J Transplant.

2023 Jun;37(2):85-94. 10.4285/kjt.23.0009.

Barriers to the identification of possible organ donors among brain-injured patients admitted to intensive care units

- Affiliations

-

- 1Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

- 2Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Hospital Sultanah Aminah, Johor Bahru, Malaysia

- 3Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Hospital Queen Elizabeth, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

- 4Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Jesselton Medical Center, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

- 5Department of Accident and Emergency Medicine, Hospital Wanita & Kanak-Kanak, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

- KMID: 2544112

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/kjt.23.0009

Abstract

- Background

Improving organ donation rates requires better detection of possible organ donors, which in turn necessitates identifying barriers preventing the identification of possible organ donors. The objectives of this study were to determine the actual rate of possible deceased organ donors among nonreferred cases and to identify barriers to their identification as possible donors.

Methods

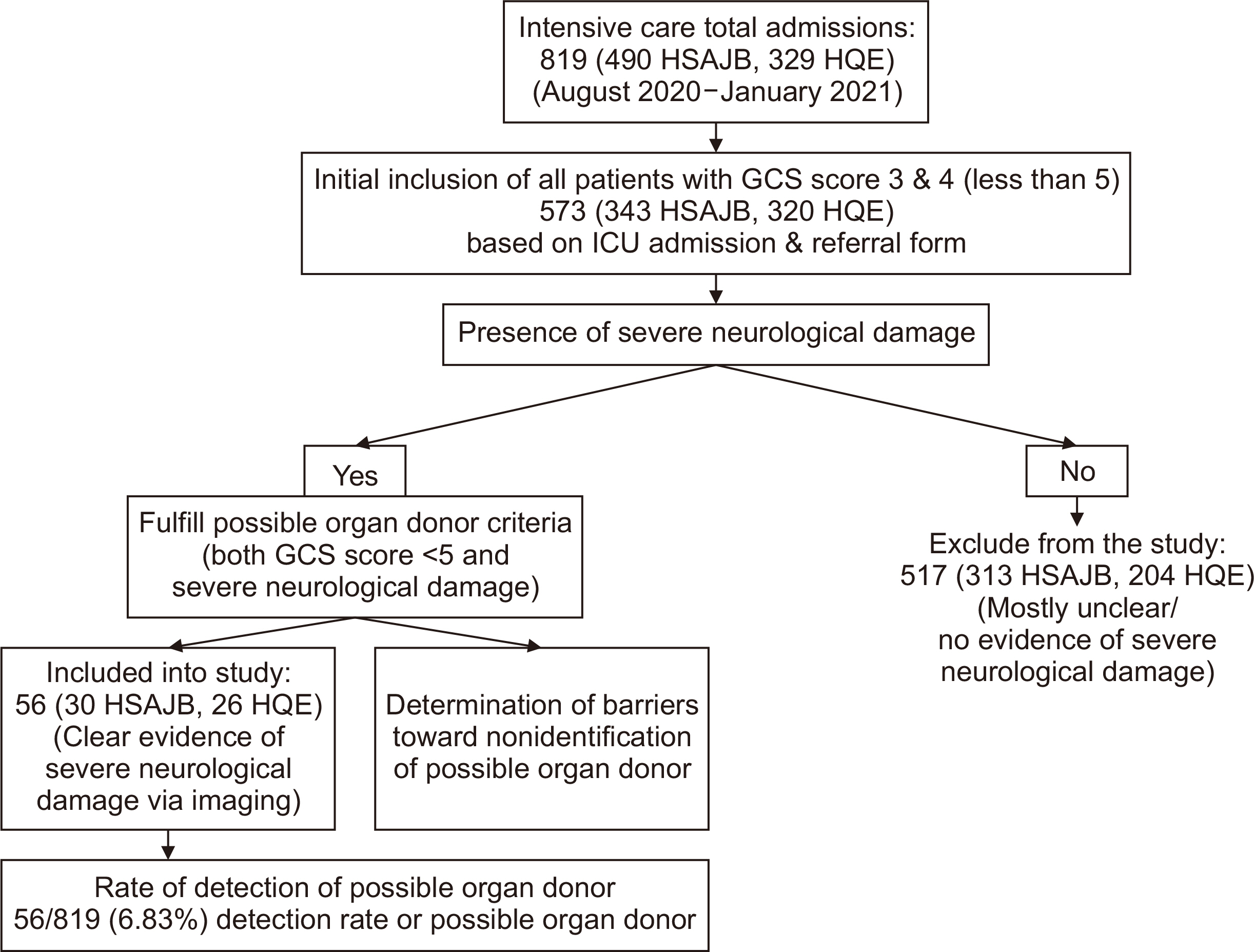

This retrospective observational study used 6 months of data collected from two intensive care units (ICUs). Possible organ donors were defined as patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale score <5 and evidence of severe neurological damage. Barriers that led to the nonidentification of these patients as possible organ donors were also identified.

Results

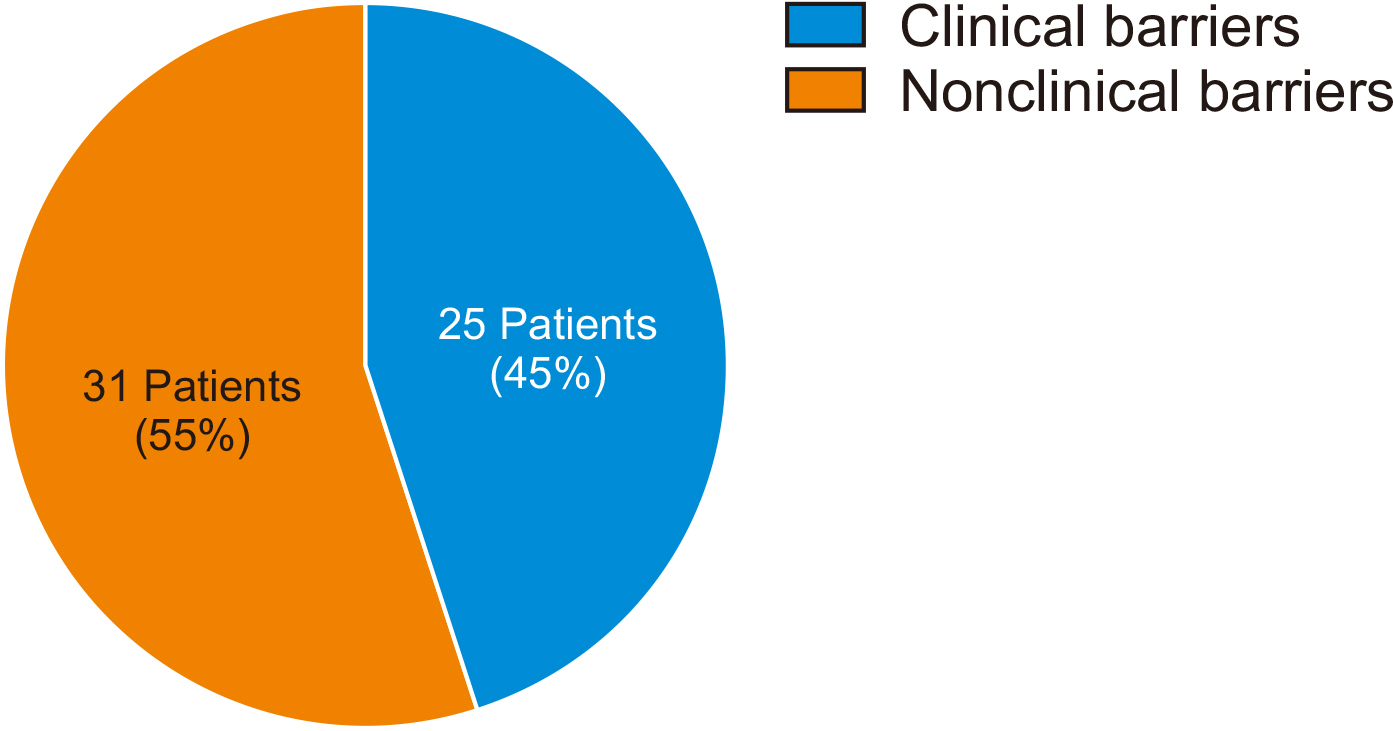

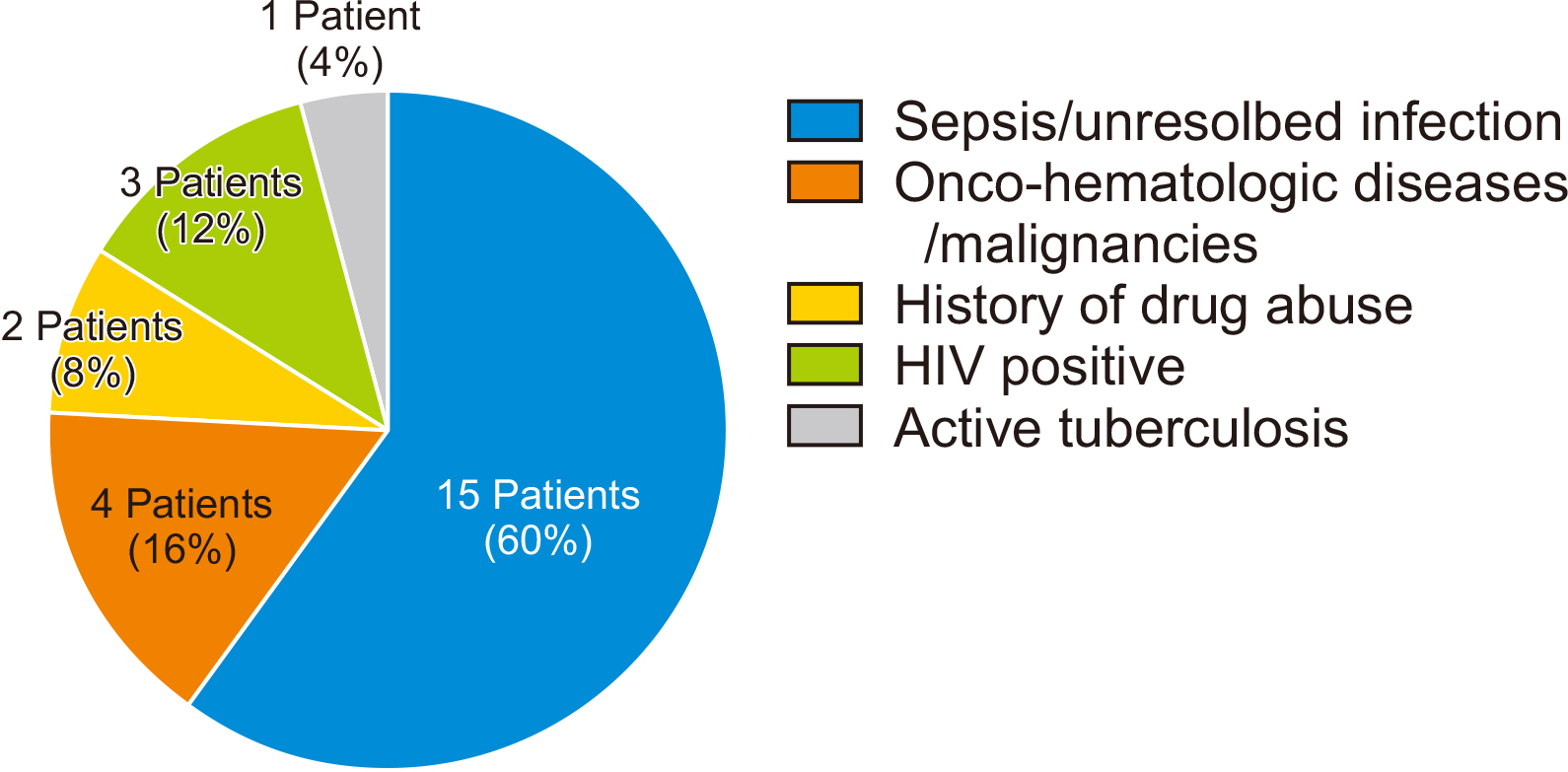

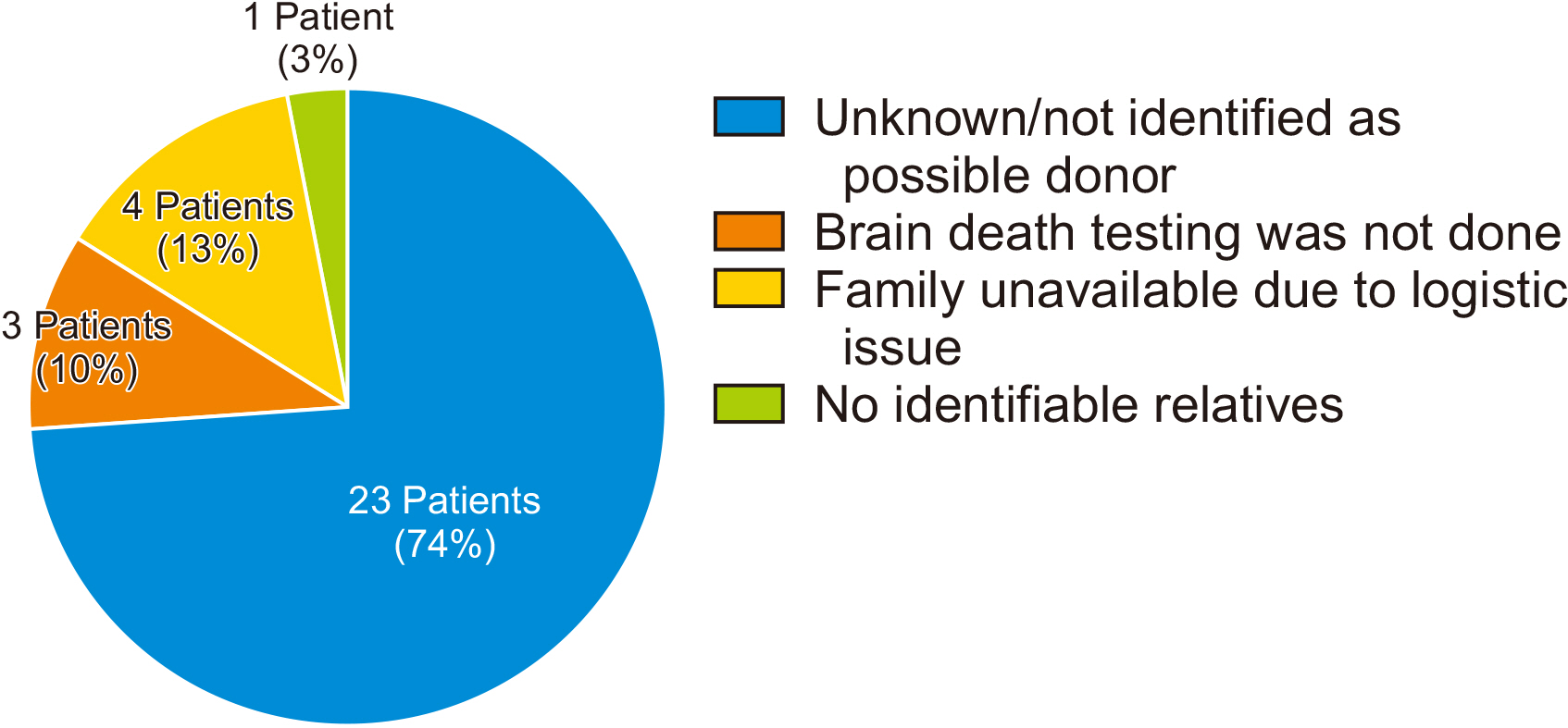

Fifty-six of 819 patients admitted to the ICUs during the study period were detected as possible organ donors, representing a 6.83% possible organ donor detection rate. Nonclinical barriers to the identification of possible organ donors were found to be more significant than clinical barriers (55% vs. 45%, respectively). The most significant nonclinical barrier was an unknown reason, despite patients being medically suitable for deceased organ donation and fulfilling the criteria for possible organ donor classification. Unresolved sepsis was the main clinical barrier.

Conclusions

The significant rate of unreferred possible deceased organ donors found in this study reveals the need to increase awareness and knowledge among clinicians of the proper detection of possible donors at an early stage to avoid the loss of possible deceased organ donors, and thereby increase the deceased organ donation rate in Malaysian hospitals.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Serri K, Marsolais P. 2017; End-of-life issues in cardiac critical care: the option of organ donation. Can J Cardiol. 33:128–34. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.10.017. PMID: 28024551.

Article2. Escudero D, Otero J. 2015; Intensive care medicine and organ donation: exploring the last frontiers? Med Intensiva. 39:373–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.medine.2015.01.001.

Article3. Lewis A, Koukoura A, Tsianos GI, Gargavanis AA, Nielsen AA, Vassiliadis E. 2021; Organ donation in the US and Europe: the supply vs demand imbalance. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 35:100585. DOI: 10.1016/j.trre.2020.100585. PMID: 33071161.

Article4. Matesanz R, Domínguez-Gil B, Coll E, Mahíllo B, Marazuela R. 2017; How Spain reached 40 deceased organ donors per million population. Am J Transplant. 17:1447–54. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.14104. PMID: 28066980.

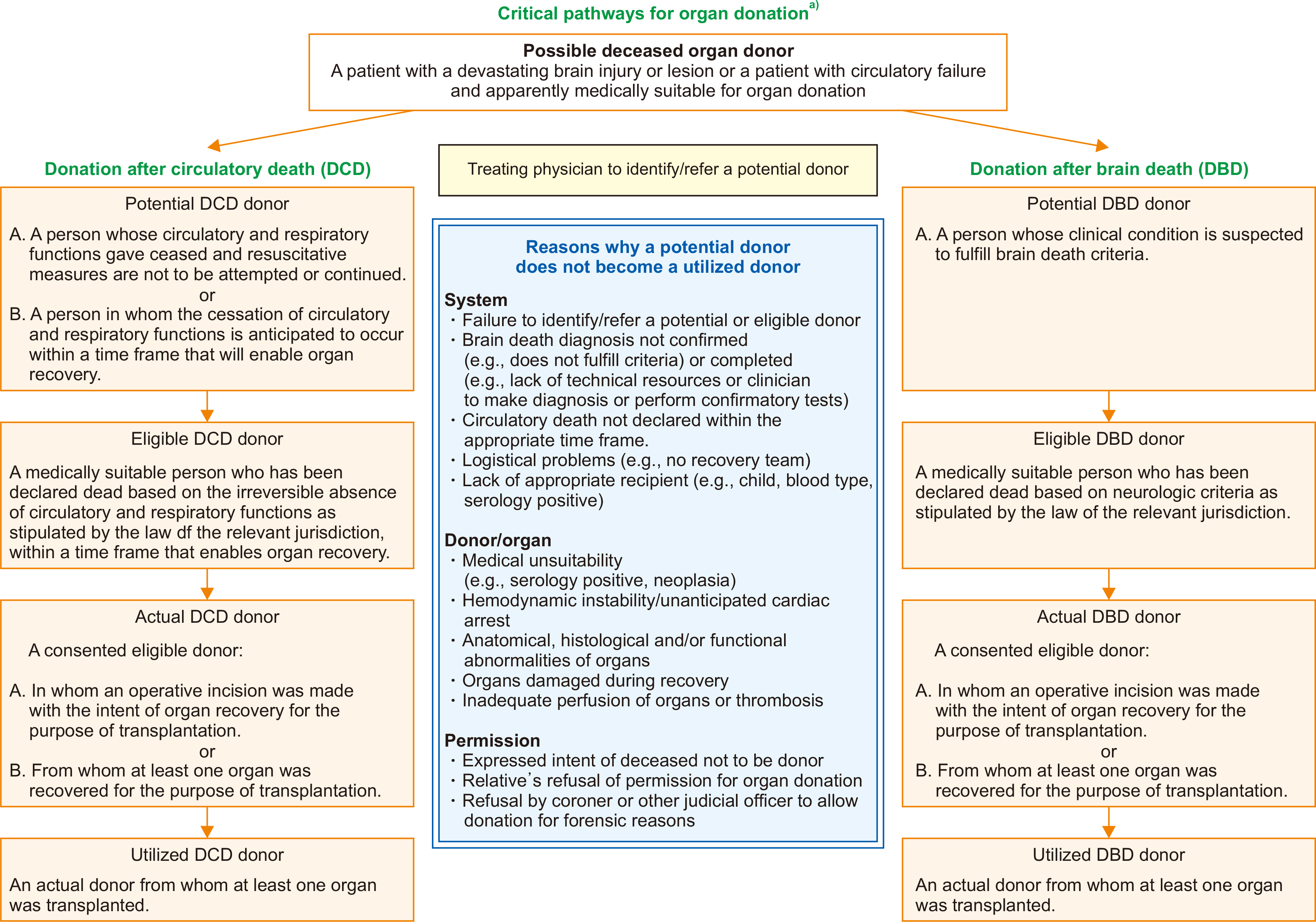

Article5. Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation (GODT). 2019. 2019 Annual data report [Internet]. GODT;Available from: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/. cited 2021 Dec 1.6. Domínguez-Gil B, Delmonico FL, Shaheen FA, Matesanz R, O'Connor K, Minina M, et al. 2011; The critical pathway for deceased donation: reportable uniformity in the approach to deceased donation. Transpl Int. 24:373–8. DOI: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01243.x. PMID: 21392129.

Article7. Thuong M, Ruiz A, Evrard P, Kuiper M, Boffa C, Akhtar MZ, et al. 2016; New classification of donation after circulatory death donors definitions and terminology. Transpl Int. 29:749–59. DOI: 10.1111/tri.12776. PMID: 26991858.

Article8. Westphal GA, Garcia VD, Souza RL, Franke CA, Vieira KD, Birckholz VR, et al. 2016; Guidelines for the assessment and acceptance of potential brain-dead organ donors. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 28:220–55. DOI: 10.5935/0103-507X.20160049. PMID: 27737418. PMCID: PMC5051181.

Article9. National Transplant Resource Center (NTRC). 2020. 2020 Current deceased donation report [Internet]. NTRC;Available from: https://www.dermaorgan.gov.my/. cited 2020 Nov 1.10. Sandiumenge A, Domínguez-Gil B, Pont T, Sánchez Ibáñez J, Chandrasekar A, Bokhorst A, et al. 2021; Critical pathway for deceased tissue donation: a novel adaptative European systematic approach. Transpl Int. 34:865–71. DOI: 10.1111/tri.13841. PMID: 33559299. PMCID: PMC8251811.

Article11. Ling TL, Har LC, Nor MR, Ismail NI, Ismail WN. Malaysian registry of intensive care annual report 2017. Clinical Research Center, Ministry of Health Malaysia;2018.12. International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation (IRODaT). 2021. Worldwide actual deceased organ donors 2020 (PMP) [Internet]. IRODaT;Available from: https://www.irodat.org/?p=database. cited 2023 Feb 25.13. Sørensen P, Kousgaard SJ. 2017; Barriers toward organ donation in a Danish university hospital. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 61:322–7. DOI: 10.1111/aas.12853. PMID: 28070885.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Medical Management of Brain-Dead Organ Donors

- How do physicians and nurses differ in their perceived barriers to effective enteral nutrition in the intensive care unit?

- Inhaled nitric oxide for the brain dead donor with neurogenic pulmonary edema during anesthesia for organ donation: a case report

- Potential Organ Donor Pool for Renal Transplantation in Intensive Care Unit and Emergency Room : Single center study for donor action program

- Organ Donor Management