J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Jun;38(25):e194. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e194.

Can We Notice the Suicidal Warning Signs of Adolescents With Different Psychometric Profiles Before Their Death?: Analysis of Teachers’ Reports

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Preventive Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 2Center for School Mental Health, Eulji University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Social Welfare Policy, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea

- 4Institute of Behavioral Sciences in Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea

- 6Suicide and School Mental Health Institute, Hallym University, Anyang, Korea

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Nowon Eulji University Hospital, Eulji University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2544010

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e194

Abstract

- Background

This study aimed to analyze the suicidal warning signs of Korean students with different psychometric profiles based on teacher reports.

Methods

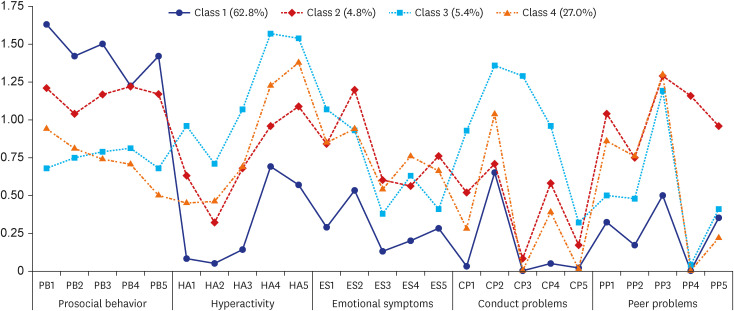

This was a retrospective cohort study based on Korean school teachers’ responses to the Student Suicide Report Form. In total, 546 consecutive cases of student suicide were reported from 2017 to 2020. After missing data were excluded, 528 cases were included. The report consisted of demographic factors, the Korean version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) for teacher reporting, and warning signs of suicide. Frequency analysis, multiple response analysis, the χ2 test, and Latent Class Analysis (LCA) were performed.

Results

Based on the scores of the Korean version of the teacher-reported SDQ, the group was divided into nonsymptomatic (n = 411) and symptomatic (n = 117) groups. Based on the LCA results, four latent hierarchical models were selected. The four classes of deceased students showed significant differences in school type (χ2 = 20.410, P < 0.01), physical illness (χ2 = 7.928, P < 0.05), mental illness (χ2 = 94.332, P < 0.001), trigger events (χ2 = 14.817, P < 0.01), self-harm experience (χ2 = 30.618, P < 0.001), suicide attempts (χ2 = 24.072, P < 0.001), depressive symptoms (χ2 = 59.561, P < 0.001), anxiety (χ2 = 58.165, P < 0.001), impulsivity (χ2 = 62.241, P < 0.001), and social problems (χ2 = 64.952, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Notably, many students who committed suicide did not have any psychiatric pathology. The proportion of the group with a prosocial appearance was also high. Therefore, the actual suicide warning signals were similar regardless of students’ difficulties and prosocial behaviors, so it is necessary to include this information in gatekeeper education.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lee HE, Kim I, Kim MH, Kawachi I. Increased risk of suicide after occupational injury in Korea. Occup Environ Med. 2021; 78(1):43–45. PMID: 32796094.2. Kwak CW, Ickovics JR. Adolescent suicide in South Korea: Risk factors and proposed multi-dimensional solution. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019; 43:150–153. PMID: 31151083.3. Lee D, Jung S, Park S, Lee K, Kweon YS, Lee EJ, et al. Youth suicide in Korea across the educational stages. Crisis. 2020; 41(3):187–195. PMID: 31512944.4. Samuolis J, Harrison AJ, Flanagan K. Evaluation of a peer-led implementation of a suicide prevention gatekeeper training program for college students. Crisis. 2020; 41(5):331–336. PMID: 31859562.5. Fond G, Zendjidjian X, Boucekine M, Brunel L, Llorca PM, Boyer L. The World Health Organization (WHO) dataset for guiding suicide prevention policies: a 3-decade French national survey. J Affect Disord. 2015; 188:232–238. PMID: 26368948.6. Van Orden KA, Joiner TE Jr, Hollar D, Rudd MD, Mandrusiak M, Silverman MM. A test of the effectiveness of a list of suicide warning signs for the public. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006; 36(3):272–287. PMID: 16805655.7. King KA. Developing a comprehensive school suicide prevention program. J Sch Health. 2001; 71(4):132–137. PMID: 11354981.8. Ramchand R, Franklin E, Thornton E, Deland S, Rouse J. Opportunities to intervene? “Warning signs” for suicide in the days before dying. Death Stud. 2017; 41(6):368–375. PMID: 28129088.9. Moskos M, Olson L, Halbern S, Keller T, Gray D. Utah youth suicide study: psychological autopsy. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005; 35(5):536–546. PMID: 16268770.10. Hallym University. An In-depth Analysis of the Causes of Suicide Deaths in Children and Adolescents Based on Reports of Bereaved Families in 2015–2020. Anyang, Korea: Hallym University Suicide and School Mental Health Institute;2020.11. Terpstra S, Beekman A, Abbing J, Jaken S, Steendam M, Gilissen R. Suicide prevention gatekeeper training in the Netherlands improves gatekeepers’ knowledge of suicide prevention and their confidence to discuss suicidality, an observational study. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18(1):637. PMID: 29776415.12. Rodway C, Tham SG, Turnbull P, Kapur N, Appleby L. Suicide in children and young people: can it happen without warning? J Affect Disord. 2020; 275:307–310. PMID: 32734923.13. Lee MS, Jhone JH, Kim JB, Kweon YS, Hong HJ. Characteristics of Korean children and adolescents who die by suicide based on teachers’ reports. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6812. PMID: 35682396.14. Barbot B, Eff H, Weiss SR, McCarthy JB. The role of psychopathology in the relationship between history of maltreatment and suicide attempts among children and adolescent inpatients. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021; 26(2):114–121. PMID: 32424956.15. Berona J, Horwitz AG, Czyz EK, King CA. Psychopathology profiles of acutely suicidal adolescents: associations with post-discharge suicide attempts and rehospitalization. J Affect Disord. 2017; 209:97–104. PMID: 27894037.16. Jung S, Lee D, Park S, Lee K, Kweon YS, Lee EJ, et al. Gender differences in Korean adolescents who died by suicide based on teacher reports. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019; 13(1):12. PMID: 30899325.17. Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997; 38(5):581–586. PMID: 9255702.18. Ahn JS, Jun SK, Han JK, Noh KS, Goodman R. The development of a Korean Version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2003; 42(1):141–147.19. Jeon M, Cho HN, Bhang SY, Hwang JW, Park EJ, Lee YJ. Development and a pilot application process of the Korean psychological autopsy checklist for adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2018; 15(5):490–498.20. Korea Psychological Autopsy Center (KPAC). Warning Sign of Suicide. Seoul, Korea: Korea Psychological Autopsy Center;2020.21. Jeon M, Cho HN, Bhang SY, Hwang JW, Park EJ, Lee YJ. Development and a pilot application process of the Korean psychological autopsy checklist for adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2018; 15(5):490–498.22. Song B, Hu W, Hu W, Yang R, Li D, Guo C, et al. Physical disorders are associated with health risk behaviors in Chinese adolescents: a Latent Class Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(6):2139. PMID: 32210169.23. Kutcher S, Wei Y, Behzadi P. School- and community-based youth suicide prevention interventions: hot idea, hot air, or sham? Can J Psychiatry. 2017; 62(6):381–387. PMID: 27407073.24. Kim EJ, Kim Y, Lee G, Choi JH, Yook V, Shin MH, et al. Comparing warning signs of suicide between suicide decedents with depression and those non-diagnosed psychiatric disorders. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2022; 52(2):178–189. PMID: 33638573.25. Dueñas JM, Fernández M, Morales-Vives F. What is the protective role of perceived social support and religiosity in suicidal ideation in young adults? J Gen Psychol. 2020; 147(4):432–447. PMID: 31782691.26. Fisher D. The literacy educator’s role in suicide prevention. J Adolesc Adult Literacy. 2005; 48(5):364–373.27. Rudd MD, Berman AL, Joiner TE Jr, Nock MK, Silverman MM, Mandrusiak M, et al. Warning signs for suicide: theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006; 36(3):255–262. PMID: 16805653.28. Crawford S, Caltabiano NJ. The school professionals’ role in identification of youth at risk of suicide. Aust J Teach Educ. 2009; 34(2):28–39.29. Brock SE, Lieberman R, Cruz MA, Coad R. Conducting school suicide risk assessment in distance learning environments. Contemp Sch Psychol. 2021; 25(1):3–11. PMID: 33425480.30. Beautrais AL. Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160(6):1093–1099. PMID: 12777267.31. Freuchen A, Kjelsberg E, Lundervold AJ, Grøholt B. Differences between children and adolescents who commit suicide and their peers: a psychological autopsy of suicide victims compared to accident victims and a community sample. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012; 6(1):1. PMID: 22216948.32. Lee MS, Han SH, Kang JY, Kim JB. The effects of household financial difficulties caused by COVID-19 on suicidal tendencies of adolescents: application of propensity score matching analysis. J Korean Soc Sch Community Health Educ. 2021; 22(2):1–14.33. Becker M, Correll CU. Suicidality in childhood and adolescence. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020; 117(15):261–267. PMID: 32449889.34. Berger GE, Della Casa A, Pauli D. Prevention and interventions for suicidal youth considerations for health professionionals in Switzerland. Ther Umsch. 2015; 72(10):619–632. PMID: 26423880.35. Cleary SD. Adolescent victimization and associated suicidal and violent behaviors. Adolescence. 2000; 35(140):671–682. PMID: 11214206.36. Khalsa HM, Salvatore P, Hennen J, Baethge C, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal events and accidents in 216 first-episode bipolar I disorder patients: predictive factors. J Affect Disord. 2008; 106(1-2):179–184. PMID: 17614135.37. Chen CM, Harford TC, Grant BF, Chou SP. Association between aggressive and non-fatal suicidal behaviors among U.S. high school students. J Affect Disord. 2020; 277:649–657. PMID: 32911215.38. Liu J. Need to establish a new adolescent suicide prevention programme in South Korea. Gen Psychiatr. 2020; 33(4):e100200. PMID: 32695959.39. Na KS, Park SC, Kwon SJ, Kim M, Kim HJ, Baik M, et al. Contents of the standardized suicide prevention program for gatekeeper intervention in Korea, version 2.0. Psychiatry Investig. 2020; 17(11):1149–1157.40. Teo AR, Andrea SB, Sakakibara R, Motohara S, Matthieu MM, Fetters MD. Brief gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in an ethnic minority population: a controlled intervention. BMC Psychiatry. 2016; 16(1):211. PMID: 27388600.41. Morton M, Wang S, Tse K, Chung C, Bergmans Y, Ceniti A, et al. Gatekeeper training for friends and family of individuals at risk of suicide: a systematic review. J Community Psychol. 2021; 49(6):1838–1871. PMID: 34125969.42. Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, Stone DM, Gaylor E, Wilkins N, et al. Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students - youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020; 69(1):47–55. PMID: 32817610.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Risk Factors of Suicidal Ideation according to Age Groups among the Adolescents in Korea

- Factors on the Pathway from Trauma to Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents

- Association of Suicidal Ideation With Dental Pain among Korean Adolescents

- The Mediating Role of Depression Severity on the Relationship Between Suicidal Ideation and Self-Injury in Adolescents With Major Depressive Disorder

- Predictors of Suicidal Ideation for Adolescents by Gender