J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Apr;38(15):e125. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e125.

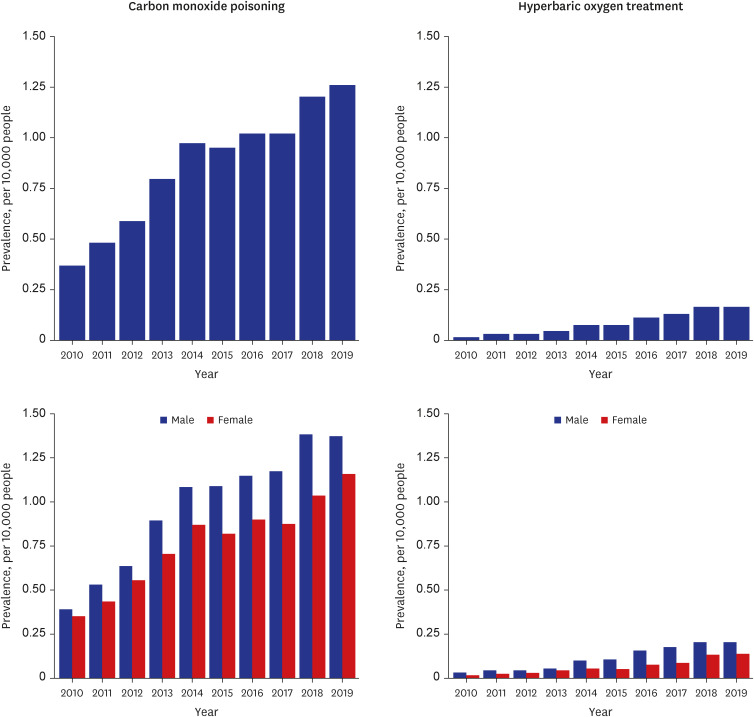

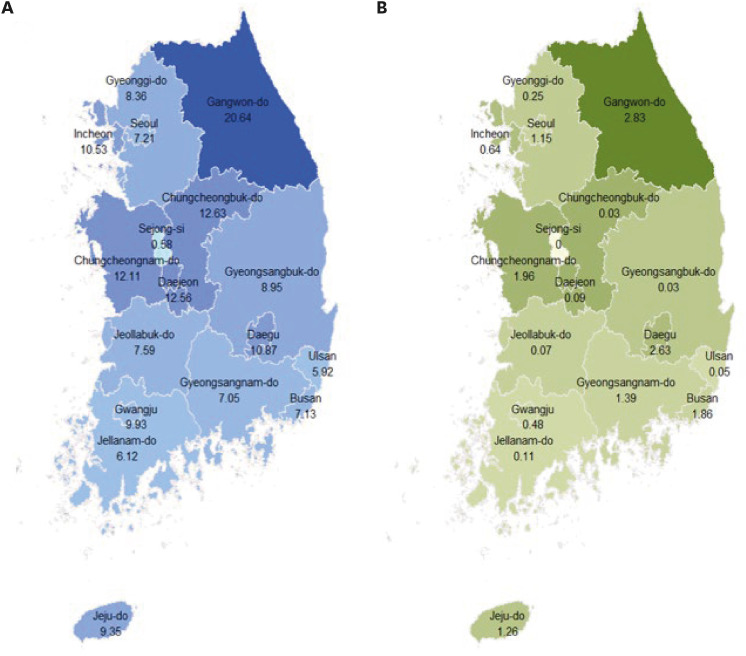

Prevalence of Carbon Monoxide Poisoning and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in Korea: Analysis of National Claims Data in 2010–2019

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Biostatistics Collaboration Unit, Medical Research Center, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Biomedical Statistics Center, Research Institute for Future Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2541560

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e125

Abstract

- This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning and the provision of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in South Korea. We used data from the Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment service. In total, 44,361 patients with CO poisoning were identified across 10 years (2010–2019). The prevalence of CO poisoning was found to be 8.64/10,000 people, with a gradual annual increment. The highest prevalence was 11.01/10,000 individuals, among those aged 30–39 years. In 2010, HBOT was claimed from 15 hospitals, and increased to 30 hospitals in 2019. A total of 4,473 patients received HBOT in 10 years and 2,684 (60%) were treated for more than 2 hours. This study suggested that the prevalence of both CO poisoning and HBOT in Korea gradually increased over the past 10 years, and disparities in prevalence were observed by region.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kim JH, Lim AY, Cheong HK. Trends of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning in Korea, 1951-2018. Epidemiol Health. 2020; 42:e2020062. PMID: 32882118.2. Statistics Korea. Korean Statistical Information Service homepage. Updated 2023. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://kosis.kr .3. Kim YJ, Sohn CH, Oh BJ, Lim KS, Kim WY. Carbon monoxide poisoning during camping in Korea. Inhal Toxicol. 2016; 28(14):719–723. PMID: 27919173.4. Choi YR, Cha ES, Chang SS, Khang YH, Lee WJ. Suicide from carbon monoxide poisoning in South Korea: 2006-2012. J Affect Disord. 2014; 167:322–325. PMID: 25016488.5. Choi IS. Carbon monoxide poisoning: systemic manifestations and complications. J Korean Med Sci. 2001; 16(3):253–261. PMID: 11410684.6. Rhee B, Kim HH, Choi S, Min YG. Incidence patterns of nervous system diseases after carbon monoxide poisoning: a retrospective longitudinal study in South Korea from 2012 to 2018. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2021; 8(2):111–119. PMID: 34237816.7. Weaver LK. Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(12):1217–1225. PMID: 19297574.8. Huang CC, Ho CH, Chen YC, Lin HJ, Hsu CC, Wang JJ, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is associated with lower short- and long-term mortality in patients with carbon monoxide poisoning. Chest. 2017; 152(5):943–953. PMID: 28427969.9. Lee SM, Heo T, Kim G, Kim H. Current status and development direction of hyperbaric medicine in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2022; 65(4):232–238.10. Lee S, Lee J, Kim KH, Park J, Shin DW, Kim H, et al. Trends of carbon monoxide poisoning patients in emergency department: NEDIS (National Emergency Department Information System). J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2021; 32(1):27–35.11. Bae S, Lee J, Kim K, Park J, Shin D, Kim H, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of carbon monoxide poisoning: emergency department based injury in-depth surveillance of twenty hospitals. J Korean Soc Clin Toxicol. 2016; 14(2):122–128.12. National Health Insurance Service. National Health Insurance population distribution. Updated 2022. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.nhis.or.kr/nhis/policy/wbhada01700m01.do .13. Hampson NB. U.S. mortality due to carbon monoxide poisoning, 1999-2014. Accidental and intentional deaths. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016; 13(10):1768–1774. PMID: 27466698.14. Roca-Barceló A, Crabbe H, Ghosh R, Freni-Sterrantino A, Fletcher T, Leonardi G, et al. Temporal trends and demographic risk factors for hospital admissions due to carbon monoxide poisoning in England. Prev Med. 2020; 136:106104. PMID: 32353574.15. Unsal Sac R, Taşar MA, Bostancı İ, Şimşek Y, Bilge Dallar Y. Characteristics of children with acute carbon monoxide poisoning in Ankara: a single centre experience. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30(12):1836–1840. PMID: 26713060.16. Jo H, Lee K, Son S, Kang H, Kim S, Roh S. Clinical characteristics of people who attempted suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning in Korea. Mood Emot. 2020; 18(3):100–109.17. Ministry of Health and Welfare (KR). Korea Foundation for Suicide Prevention. White Paper on Suicide Prevention 2022. Seoul: Korea Foundation for Suicide Prevention;2022.18. Lee T, Lee AR, Ahn MH, Jeong SY, Hong JP. Overview of suicide by charcoal burning and prevention strategies. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2014; 53(1):1–7.19. Chang SS, Lin CY, Hsu CY, Chen YY, Yip PS. Assessing the effect of restricting access to barbecue charcoal for suicide prevention in New Taipei City, Taiwan: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021; 282:795–802. PMID: 33601720.20. Ran T, Nurmagambetov T, Sircar K. Economic implications of unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning in the United States and the cost and benefit of CO detectors. Am J Emerg Med. 2018; 36(3):414–419. PMID: 28888530.21. Hampson NB. Cost effectiveness of residential carbon monoxide alarms. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2017; 44(5):393–397. PMID: 29116693.22. Christensen GM, Creswell PD, Theobald J, Meiman JG. Carbon monoxide detector effectiveness in reducing poisoning, Wisconsin 2014-2016. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2020; 58(12):1335–1341. PMID: 32163299.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Carbon Monoxide Poisoning Case in Which Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Was Not Possible Due to Iatrogenic Pneumothorax after Unnecessary Central Catheterization

- Carbon Monoxide Poisoning with Reversible Hemiparesis: Case Reports

- Carbon Monoxide Poisoning in the Unusual Circumstance: Four Cases Report

- Cerebral Infarction Followed by Hemorrhagic Transformation Accompanied by Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

- Pulmonary edema in acute carbon monoxide poisoning