Korean J Transplant.

2023 Mar;37(1):11-18. 10.4285/kjt.23.0011.

Characteristics and management of thrombotic microangiopathy in kidney transplantation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Transplantation and Vascular Surgery, Korea University Anam Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2541308

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4285/kjt.23.0011

Abstract

- Thrombotic microangiopathy is not a rare complication of kidney transplantation and is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute kidney injury with extensive thrombosis of the arterioles and capillaries. Various factors can cause thrombotic microangiopathy after kidney transplantation, including surgery, warm and cold ischemia-reperfusion injury, exposure to immunosuppressants, infection, and rejection. Many recent studies on atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome have described genetic abnormalities related to excessive activation of the alternative complement pathway. The affected patients’ genetic backgrounds revealed significant genetic heterogeneity in several genes involved in complement regulation, including the complement factor H, complement factor H-related proteins, complement factor I, complement factor B, complement component 3, and CD46 genes in the alternative complement pathway. Although clinical studies have provided a better understanding of the pathogenesis of diseases, the diverse triggers present in the transplant environment can lead to thrombotic microangiopathy, along with various genetic predispositions, and it is difficult to identify the genetic background in various clinical conditions. Given the poor prognosis of posttransplant thrombotic microangiopathy, further research is necessary to improve the diagnosis and treatment protocols based on risk factors or genetic predisposition, and to develop new therapeutic agents.

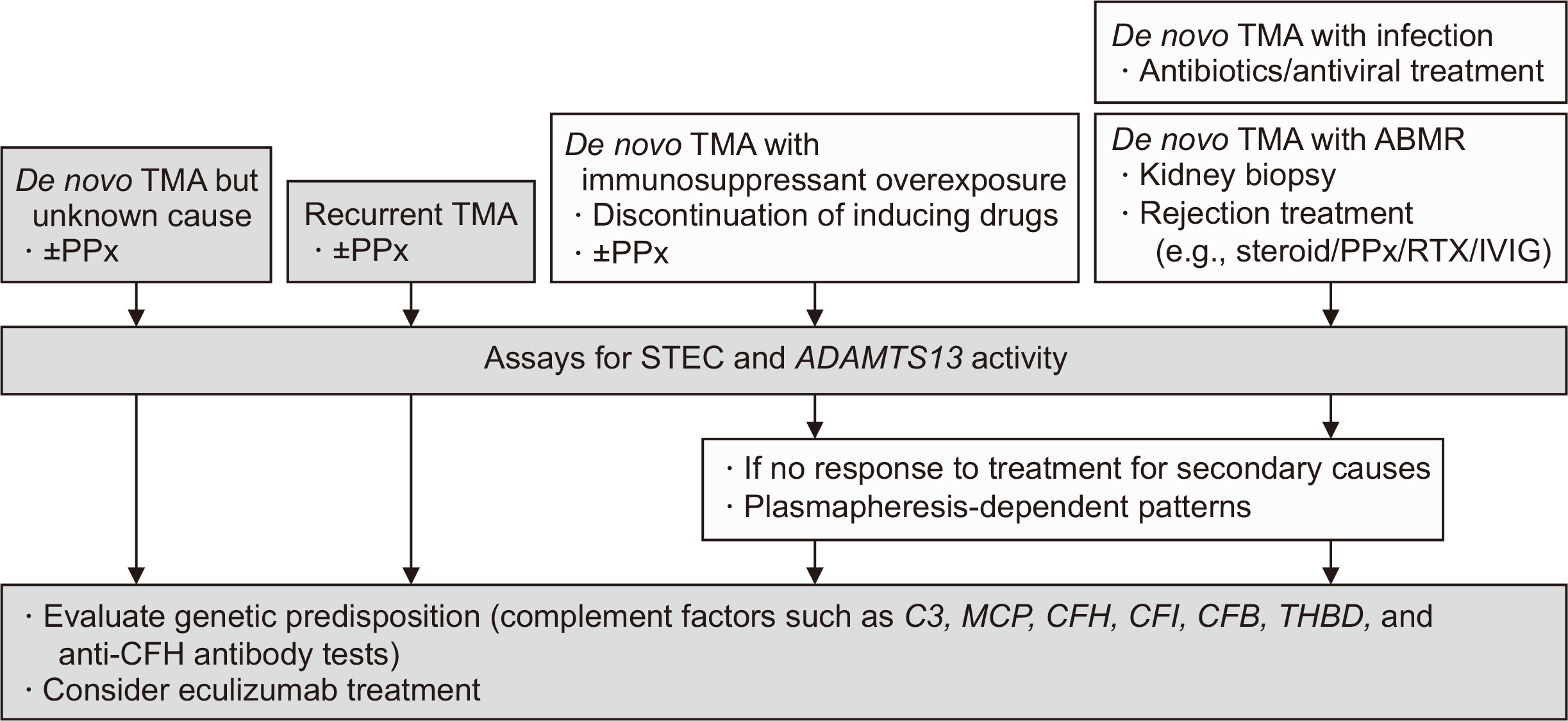

Figure

Reference

-

1. Timmermans SA, Abdul-Hamid MA, Vanderlocht J, Damoiseaux JG, Reutelingsperger CP, van Paassen P, et al. 2017; Patients with hypertension-associated thrombotic microangiopathy may present with complement abnormalities. Kidney Int. 91:1420–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.009. PMID: 28187980.2. Le Quintrec M, Lionet A, Kamar N, Karras A, Barbier S, Buchler M, et al. 2008; Complement mutation-associated de novo thrombotic microangiopathy following kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 8:1694–701. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02297.x. PMID: 18557729.3. Fakhouri F, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. 2021; Thrombotic microangiopathy in aHUS and beyond: clinical clues from complement genetics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 17:543–53. DOI: 10.1038/s41581-021-00424-4. PMID: 33953366.4. Ahlenstiel-Grunow T, Hachmeister S, Bange FC, Wehling C, Kirschfink M, Bergmann C, et al. 2016; Systemic complement activation and complement gene analysis in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli-associated paediatric haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 31:1114–21. DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gfw078. PMID: 27190382.5. Noris M, Caprioli J, Bresin E, Mossali C, Pianetti G, Gamba S, et al. 2010; Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 5:1844–59. DOI: 10.2215/CJN.02210310. PMID: 20595690. PMCID: PMC2974386.6. Schaefer F, Ardissino G, Ariceta G, Fakhouri F, Scully M, Isbel N, et al. 2018; Clinical and genetic predictors of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome phenotype and outcome. Kidney Int. 94:408–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.02.029. PMID: 29907460.7. Lee H, Kang E, Kang HG, Kim YH, Kim JS, Kim HJ, et al. 2020; Consensus regarding diagnosis and management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Korean J Intern Med. 35:25–40. DOI: 10.3904/kjim.2019.388. PMID: 31935318. PMCID: PMC6960041.8. Zarifian A, Meleg-Smith S, O'donovan R, Tesi RJ, Batuman V. 1999; Cyclosporine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in renal allografts. Kidney Int. 55:2457–66. DOI: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00492.x. PMID: 10354295.9. Reynolds JC, Agodoa LY, Yuan CM, Abbott KC. 2003; Thrombotic microangiopathy after renal transplantation in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 42:1058–68. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.07.008. PMID: 14582050.10. Saikumar Doradla LP, Lal H, Kaul A, Bhaduaria D, Jain M, Prasad N, et al. 2020; Clinical profile and outcomes of De novo posttransplant thrombotic microangiopathy. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 31:160–8. DOI: 10.4103/1319-2442.279936. PMID: 32129209.11. Zuber J, Fakhouri F, Roumenina LT, Loirat C, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. French Study Group for aHUS/C3G. 2012; Use of eculizumab for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 8:643–57. DOI: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.214. PMID: 23026949.12. Goodship TH, Cook HT, Fakhouri F, Fervenza FC, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Kavanagh D, et al. 2017; Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: conclusions from a "Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes" (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 91:539–51. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.005. PMID: 27989322.13. Le Quintrec M, Zuber J, Moulin B, Kamar N, Jablonski M, Lionet A, et al. 2013; Complement genes strongly predict recurrence and graft outcome in adult renal transplant recipients with atypical hemolytic and uremic syndrome. Am J Transplant. 13:663–75. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.12077. PMID: 23356914.14. Noris M, Remuzzi G. 2013; Managing and preventing atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome recurrence after kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 22:704–12. DOI: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328365b3fe. PMID: 24076560.15. Avila A, Gavela E, Sancho A. 2021; Thrombotic microangiopathy after kidney transplantation: an underdiagnosed and potentially reversible entity. Front Med (Lausanne). 8:642864. DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2021.642864. PMID: 33898482. PMCID: PMC8063690.16. Legendre CM, Campistol JM, Feldkamp T, Remuzzi G, Kincaid JF, Lommele A, et al. 2017; Outcomes of patients with atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome with native and transplanted kidneys treated with eculizumab: a pooled post hoc analysis. Transpl Int. 30:1275–83. DOI: 10.1111/tri.13022. PMID: 28801959.17. Thurman JM, Ljubanovic D, Edelstein CL, Gilkeson GS, Holers VM. 2003; Lack of a functional alternative complement pathway ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure in mice. J Immunol. 170:1517–23. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1517. PMID: 12538716.18. Naesens M, Li L, Ying L, Sansanwal P, Sigdel TK, Hsieh SC, et al. 2009; Expression of complement components differs between kidney allografts from living and deceased donors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 20:1839–51. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2008111145. PMID: 19443638. PMCID: PMC2723986.19. Petr V, Hruba P, Kollar M, Krejci K, Safranek R, Stepankova S, et al. 2021; Rejection-associated phenotype of de novo thrombotic microangiopathy represents a risk for premature graft loss. Transplant Direct. 7:e779. DOI: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001239. PMID: 34712779. PMCID: PMC8547913.20. Noris M, Remuzzi G. 2009; Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 361:1676–87. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra0902814. PMID: 19846853.21. Burke GW, Ciancio G, Cirocco R, Markou M, Olson L, Contreras N, et al. 1999; Microangiopathy in kidney and simultaneous pancreas/kidney recipients treated with tacrolimus: evidence of endothelin and cytokine involvement. Transplantation. 68:1336–42. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-199911150-00020. PMID: 10573073.22. Brown Z, Neild GH. 1987; Cyclosporine inhibits prostacyclin production by cultured human endothelial cells. Transplant Proc. 19(1 Pt 2):1178–80.23. Garcia-Maldonado M, Kaufman CE, Comp PC. 1991; Decrease in endothelial cell-dependent protein C activation induced by thrombomodulin by treatment with cyclosporine. Transplantation. 51:701–5. DOI: 10.1097/00007890-199103000-00030. PMID: 1848730.24. Renner B, Klawitter J, Goldberg R, McCullough JW, Ferreira VP, Cooper JE, et al. 2013; Cyclosporine induces endothelial cell release of complement-activating microparticles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 24:1849–62. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2012111064. PMID: 24092930. PMCID: PMC3810078.25. Karthikeyan V, Parasuraman R, Shah V, Vera E, Venkat KK. 2003; Outcome of plasma exchange therapy in thrombotic microangiopathy after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 3:1289–94. DOI: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00222.x. PMID: 14510703.26. Koppula S, Yost SE, Sussman A, Bracamonte ER, Kaplan B. 2013; Successful conversion to belatacept after thrombotic microangiopathy in kidney transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 27:591–7. DOI: 10.1111/ctr.12170. PMID: 23923969.

Article27. Ashman N, Chapagain A, Dobbie H, Raftery MJ, Sheaff MT, Yaqoob MM. 2009; Belatacept as maintenance immunosuppression for postrenal transplant de novo drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Transplant. 9:424–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02482.x. PMID: 19120084.28. Yun SH, Lee JH, Oh JS, Kim SM, Sin YH, Kim Y, et al. 2016; Overcome of drug induced thrombotic microangiopathy after kidney transplantation by using belatacept for maintenance immunosuppression. J Korean Soc Transplant. 30:38–43. DOI: 10.4285/jkstn.2016.30.1.38.

Article29. Stegall MD, Chedid MF, Cornell LD. 2012; The role of complement in antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 8:670–8. DOI: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.212. PMID: 23026942.

Article30. Wu K, Budde K, Schmidt D, Neumayer HH, Lehner L, Bamoulid J, et al. 2016; The inferior impact of antibody-mediated rejection on the clinical outcome of kidney allografts that develop de novo thrombotic microangiopathy. Clin Transplant. 30:105–17. DOI: 10.1111/ctr.12645. PMID: 26448478.31. Satoskar AA, Pelletier R, Adams P, Nadasdy GM, Brodsky S, Pesavento T, et al. 2010; De novo thrombotic microangiopathy in renal allograft biopsies-role of antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant. 10:1804–11. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03178.x. PMID: 20659088.

Article32. Noris M, Remuzzi G. 2010; Thrombotic microangiopathy after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 10:1517–23. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03156.x. PMID: 20642678.33. Cornell LD, Schinstock CA, Gandhi MJ, Kremers WK, Stegall MD. 2015; Positive crossmatch kidney transplant recipients treated with eculizumab: outcomes beyond 1 year. Am J Transplant. 15:1293–302. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.13168. PMID: 25731800.

Article34. Schinstock CA, Bentall AJ, Smith BH, Cornell LD, Everly M, Gandhi MJ, et al. 2019; Long-term outcomes of eculizumab-treated positive crossmatch recipients: allograft survival, histologic findings, and natural history of the donor-specific antibodies. Am J Transplant. 19:1671–83. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.15175. PMID: 30412654. PMCID: PMC6509017.35. Montgomery RA, Orandi BJ, Racusen L, Jackson AM, Garonzik-Wang JM, Shah T, et al. 2016; Plasma-derived C1 esterase inhibitor for acute antibody-mediated rejection following kidney transplantation: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Am J Transplant. 16:3468–78. DOI: 10.1111/ajt.13871. PMID: 27184779.36. Siedlecki AM, Isbel N, Vande Walle J, James Eggleston J, Cohen DJ. Global aHUS Registry. 2018; Eculizumab use for kidney transplantation in patients with a diagnosis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int Rep. 4:434–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.11.010. PMID: 30899871. PMCID: PMC6409407.37. Zuber J, Le Quintrec M, Krid S, Bertoye C, Gueutin V, Lahoche A, et al. 2012; Eculizumab for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome recurrence in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 12:3337–54. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04252.x. PMID: 22958221.

Article38. Zuber J, Frimat M, Caillard S, Kamar N, Gatault P, Petitprez F, et al. 2019; Use of highly individualized complement blockade has revolutionized clinical outcomes after kidney transplantation and renal epidemiology of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 30:2449–63. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2019040331. PMID: 31575699. PMCID: PMC6900783.

Article39. Wilson C, Torpey N, Jaques B, Strain L, Talbot D, Manas D, et al. 2011; Successful simultaneous liver-kidney transplant in an adult with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with a mutation in complement factor H. Am J Kidney Dis. 58:109–12. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.008. PMID: 21601332.40. Kim S, Park E, Min SI, Yi NJ, Ha J, Ha IS, et al. 2018; Kidney transplantation in patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome due to complement factor H deficiency: impact of liver transplantation. J Korean Med Sci. 33:e4. DOI: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e4. PMID: 29215813. PMCID: PMC5729639.41. Werion A, Rondeau E. 2022; Application of C5 inhibitors in glomerular diseases in 2021. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 41:412–21. DOI: 10.23876/j.krcp.21.248. PMID: 35354244. PMCID: PMC9346396.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Changes in VWF-cleaving Metalloprotease (ADAMTS 13) activity in the thrombotic microangiopathy after kidney tranplantation

- Overcome of Drug Induced Thrombotic Microangiopathy after Kidney Transplantation by Using Belatacept for Maintenance Immunosuppression

- Thrombotic microangiopathy, rare cause of deceased donor acute kidney injury: is a donor biopsy necessary before donation?

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome Presenting as Recurrent Pancreatitis and Renal Thrombotic Microangiopathy

- A Mortality Case Caused by Thrombotic Microangiopathy after Successful Bloodless Living Donor Liver Transplantation