Ann Surg Treat Res.

2023 Apr;104(4):229-236. 10.4174/astr.2023.104.4.229.

Efficacy of the online Mindful Self-Compassion for Healthcare Communities program for surgical trainees: a prospective pilot study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Education, Ajou University, Suwon, Korea

- 2Department of Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 3College of Buddhist, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2541149

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4174/astr.2023.104.4.229

Abstract

- Purpose

The efficacy of the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) for Healthcare Communities program has not been verified. This study aims to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of the online MSC for Healthcare Communities program on burnout, stress-related health, and resilience among surgical trainees.

Methods

A single-arm pilot study was conducted at a tertiary referral academic hospital in Korea. Surgical trainees were recruited through flyer postings; therefore, a volunteer sample was used. Thus, 15 participants participated, among whom 9 were women and 11 were doctor-residents. The Self-Compassion for Healthcare Communities (SCHC) program was conducted from September to October 2021 via weekly online meetings (1 hour) for 6 weeks. The efficacy of the program was evaluated using validated scales for burnout, stress, anxiety, depression, self-compassion, and resilience before and after the intervention and 1 month later.

Results

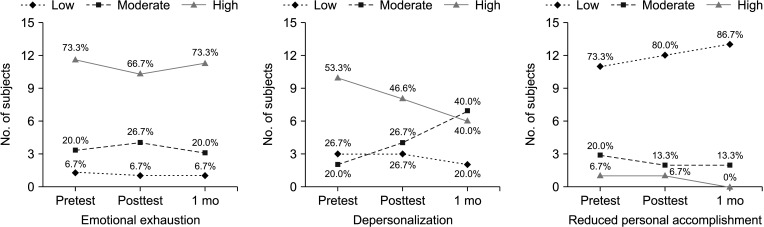

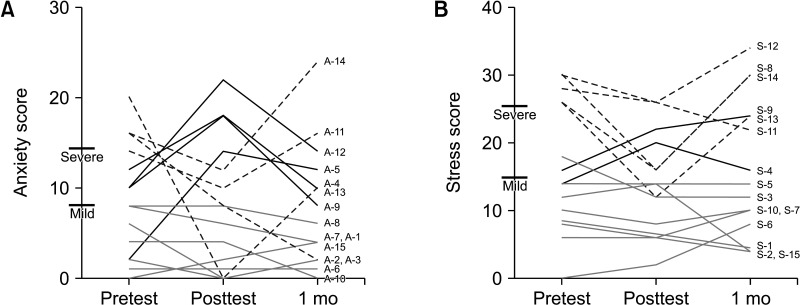

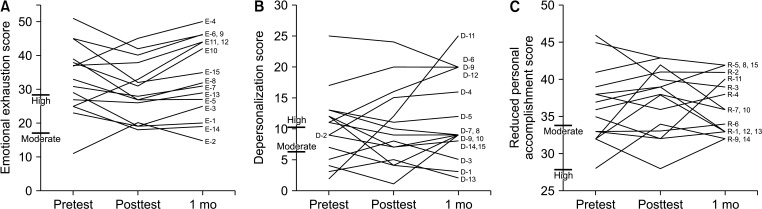

The results showed significantly reduced burnout, anxiety, and stress scores. After the program, high emotional exhaustion and depersonalization rates decreased, and personal accomplishment increased. Eight participants showed reduced anxiety postintervention, and 9 showed reduced stress. Improvements were observed between pre- and postintervention in resilience, life satisfaction, and common humanity. Changes in self-compassion predicted higher gains in resilience and greater reductions in burnout and stress.

Conclusion

The SCHC is a feasible and effective program to improve resilience, self-compassion, and life satisfaction and reduce stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout in surgical trainees. This study highlights the need to include specific mental health programs in surgical training to improve trainees’ well-being.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012; 172:1377–1385. PMID: 22911330.2. Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, Awad MM, Turnbull IR. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016; 223:440–451. PMID: 27238875.3. Shin S. The relationship between burnout and the personality characters among interns. Dongguk J Med. 2009; 16:185–192.4. Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016; 222:1230–1239. PMID: 27106639.5. Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL, O’Sullivan PS, Harris HW, Epel ES. Burnout and stress among us surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018; 226:80–90. PMID: 29107117.6. Anderson P. Physicians experience the highest suicide rate of any profession [Internet]. Medscape Medical News;2018. cited 2021 Dec 5. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/896257 .7. Freund Y. The challenge of emergency medicine facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020; 27:155. PMID: 32205709.8. de Wit K, Mercuri M, Wallner C, Clayton N, Archambault P, Ritchie K, et al. Canadian emergency physician psychological distress and burnout during the first 10 weeks of COVID-19: a mixed-methods study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020; 1:1030–1038. PMID: 32905025.9. Sotile WM, Fallon R, Orlando J. Curbing burnout hysteria with self-compassion: a key to physician resilience. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020; 40 Suppl 1:S8–S12. PMID: 32502063.10. Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008; 15:194–200. PMID: 18696313.11. Lebares CC, Hershberger AO, Guvva EV, Desai A, Mitchell J, Shen W, et al. Feasibility of formal mindfulness-based stress-resilience training among surgery interns: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2018; 153:e182734. PMID: 30167655.12. Song Y, Swendiman RA, Shannon AB, Torres-Landa S, Khan FN, Williams NN, et al. Can we coach resilience? An evaluation of professional resilience coaching as a well-being initiative for surgical interns. J Surg Educ. 2020; 77:1481–1489. PMID: 32446771.13. Neff KD, Knox MC, Long P, Gregory K. Caring for others without losing yourself: an adaptation of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Healthcare Communities. J Clin Psychol. 2020; 76:1543–1562. PMID: 32627192.14. Neff KD, Germer C. Self-compassion and psychological well-being. Seppälä EM, Simon-Thomas E, Brown SL, Worline MC, Cameron CD, Doty JR, editors. The Oxford handbook of compassion science. Oxford University Press;2017. p. 371–385.15. Olson K, Kemper KJ. Factors associated with well-being and confidence in providing compassionate care. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2014; 19:292–296. PMID: 24986815.16. Babenko O, Mosewich AD, Lee A, Koppula S. Association of physicians' self-compassion with work engagement, exhaustion, and professional life satisfaction. Med Sci (Basel). 2019; 7:29. PMID: 30759845.17. Bluth K, Lathren C, Silbersack Hickey JV, Zimmerman S, Wretman CJ, Sloane PD. Self-compassion training for certified nurse assistants in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021; 69:1896–1905. PMID: 33837539.18. Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory: manual. 2nd ed. Consulting Psychologists Press;1986.19. Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003; 2:223–250.20. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985; 49:71–75. PMID: 16367493.21. Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005; 44(Pt 2):227–239. PMID: 16004657.22. Shin WY, Kim MG, Kim JH. Developing measures of resilience for Korean adolescents and testing cross, convergent, and discriminant validity. Stud Korean Youth. 2009; 20:105–131.23. Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: the architecture of sustainable change. Rev Gen Psychol. 2005; 9:111–131.24. Golembiewski RT, Munzenrider RF, Stevenson JG. Phases of burnout: developments in concepts and applications. Praeger;1988.25. Shin H, Noh H, Jang Y, Park YM, Lee SM. A longitudinal examination of the relationship between teacher burnout and depression. J Employ Couns. 2013; 50:124–137.26. Gilbert P. Compassion: conceptualizations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge;2005.27. Galaiya R, Kinross J, Arulampalam T. Factors associated with burnout syndrome in surgeons: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2020; 102:401–407. PMID: 32326734.28. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014; 89:443–451. PMID: 24448053.29. Goldhagen BE, Kingsolver K, Stinnett SS, Rosdahl JA. Stress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015; 6:525–532. PMID: 26347361.30. Mistretta EG, Davis MC, Temkit M, Lorenz C, Darby B, Stonnington CM. Resilience training for work-related stress among health care workers: results of a randomized clinical trial comparing in-person and smartphone-delivered interventions. J Occup Environ Med. 2018; 60:559–568. PMID: 29370014.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Impact of Self-Compassion on Enhancing the Professional Quality of Life for Healthcare Workers

- Effect of Mindful Self-Compassion Training on Anxiety, Depression and Emotion Regulation

- The Relationship Between Participating in Online Parenting Communities and Health-Promoting Behaviors for Children Among First-Time Mothers: The Mediating Effect of Parental Efficacy

- Effects of a Compassion Improvement Program for Clinical Nurses on Compassion Competence and Empathic Communication

- Information Sources and Knowledge on Infant Vaccination according to Online Communities