J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Mar;38(10):e75. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e75.

Antibiogram of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Based on Sepsis Onset Location in Korea: A Multicenter Cohort Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 2Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea

- 4Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2540433

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e75

Abstract

- Background

Administration of adequate antibiotics is crucial for better outcomes in sepsis. Because no uniform tool can accurately assess the risk of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, a local antibiogram is necessary. We aimed to describe the antibiogram of MDR bacteria based on locations of sepsis onset in South Korea.

Methods

We performed a prospective observational study of adult patients diagnosed with sepsis according to Sepsis-3 from 19 institutions (13 tertiary referral and 6 universityaffiliated general hospitals) in South Korea. Patients were divided into four groups based on the respective location of sepsis onset: community, nursing home, long-term-care hospital, and hospital. Along with the antibiogram, risk factors of MDR bacteria and drug-bug match of empirical antibiotics were analyzed.

Results

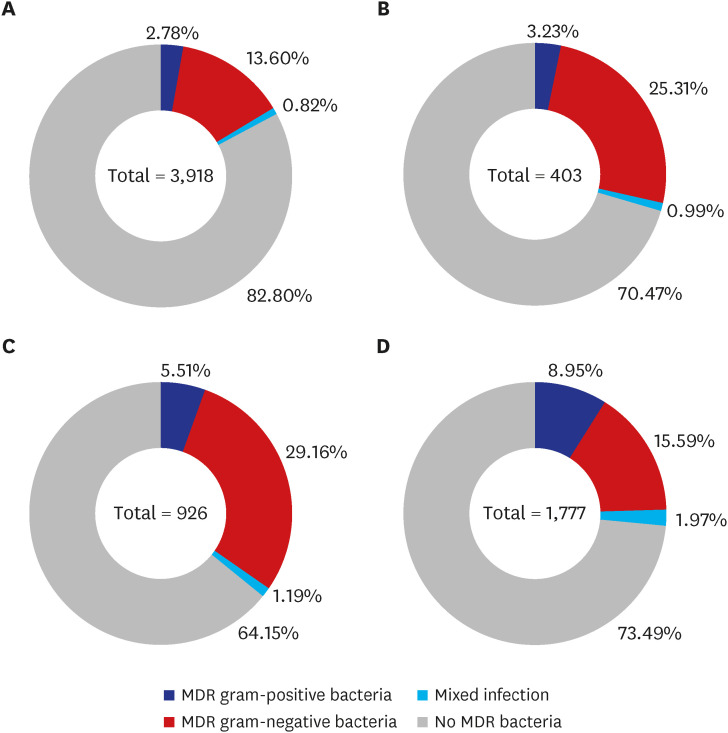

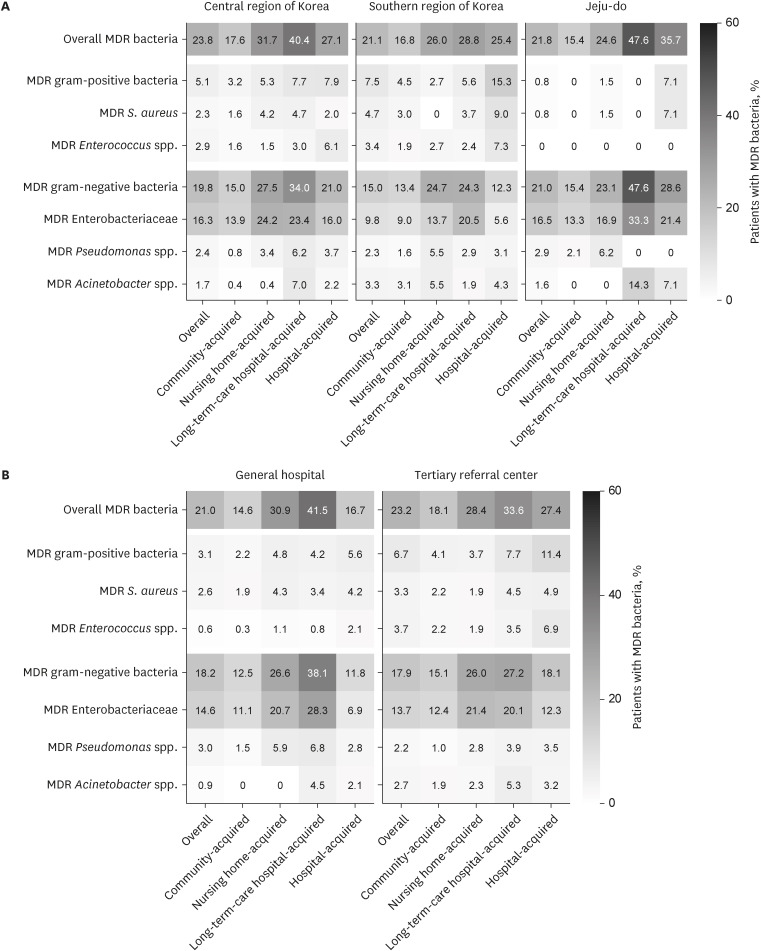

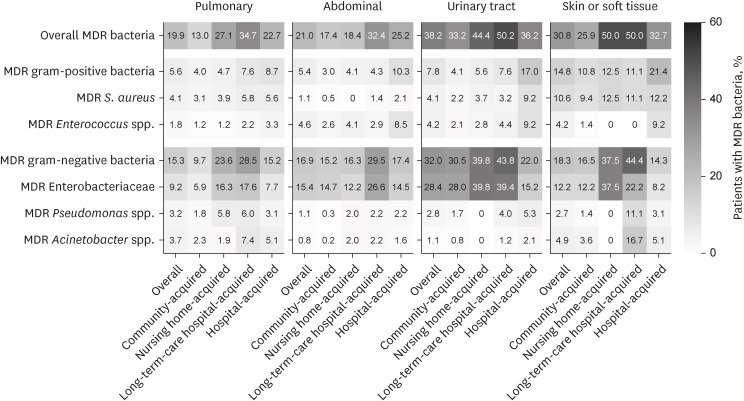

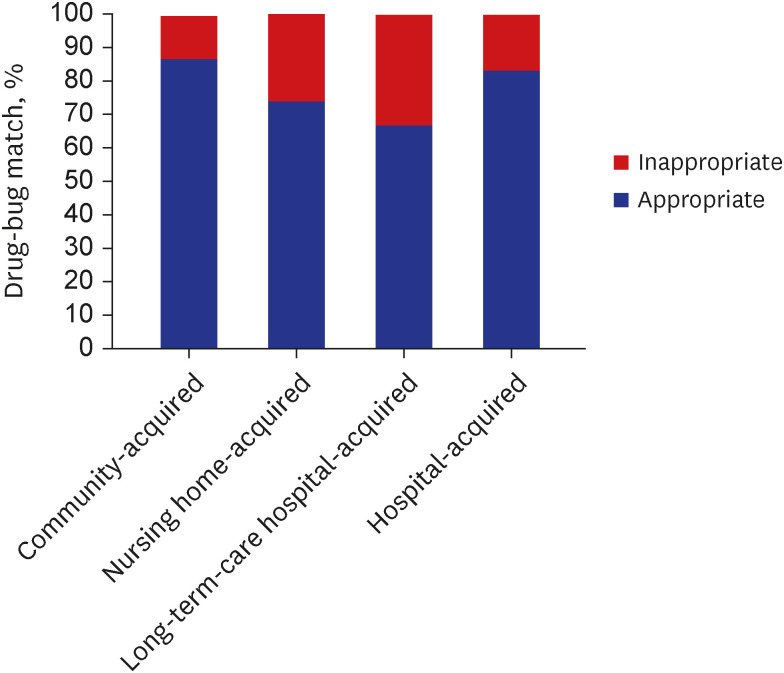

MDR bacteria were detected in 1,596 (22.7%) of 7,024 patients with gram-negative predominance. MDR gram-negative bacteria were more commonly detected in long-termcare hospital- (30.4%) and nursing home-acquired (26.3%) sepsis, whereas MDR grampositive bacteria were more prevalent in hospital-acquired (10.9%) sepsis. Such findings were consistent regardless of the location and tier of hospitals throughout South Korea. Patients with long-term-care hospital-acquired sepsis had the highest risk of MDR pathogen, which was even higher than those with hospital-acquired sepsis (adjusted odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.15–1.75) after adjustment of risk factors. The drug-bug match was lowest in patients with long-term-care hospital-acquired sepsis (66.8%).

Conclusion

Gram-negative MDR bacteria were more common in nursing home- and long-term-care hospital-acquired sepsis, whereas gram-positive MDR bacteria were more common in hospital-acquired settings in South Korea. Patients with long-term-care hospitalacquired sepsis had the highest the risk of MDR bacteria but lowest drug-bug match of initial antibiotics. We suggest that initial antibiotics be carefully selected according to the onset location in each patient.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315(8):801–810. PMID: 26903338.2. Ferrer R, Martin-Loeches I, Phillips G, Osborn TM, Townsend S, Dellinger RP, et al. Empiric antibiotic treatment reduces mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock from the first hour: results from a guideline-based performance improvement program. Crit Care Med. 2014; 42(8):1749–1755. PMID: 24717459.3. Peltan ID, Brown SM, Bledsoe JR, Sorensen J, Samore MH, Allen TL, et al. ED door-to-antibiotic time and long-term mortality in sepsis. Chest. 2019; 155(5):938–946. PMID: 30779916.4. Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021; 47(11):1181–1247. PMID: 34599691.5. Rottier WC, Bamberg YR, Dorigo-Zetsma JW, van der Linden PD, Ammerlaan HS, Bonten MJ. Predictive value of prior colonization and antibiotic use for third-generation cephalosporin-resistant enterobacteriaceae bacteremia in patients with sepsis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60(11):1622–1630. PMID: 25694654.6. Rottier WC, van Werkhoven CH, Bamberg YR, Dorigo-Zetsma JW, van de Garde EM, van Hees BC, et al. Development of diagnostic prediction tools for bacteraemia caused by third-generation cephalosporin-resistant enterobacteria in suspected bacterial infections: a nested case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018; 24(12):1315–1321. PMID: 29581056.7. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Papadimitriou E, Galanakis N, Antonopoulou A, Tsaganos T, Kanellakopoulou K, et al. Multidrug resistance to antimicrobials as a predominant factor influencing patient survival. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006; 27(6):476–481. PMID: 16707252.8. Lodise TP, Miller CD, Graves J, Furuno JP, McGregor JC, Lomaestro B, et al. Clinical prediction tool to identify patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa respiratory tract infections at greatest risk for multidrug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007; 51(2):417–422. PMID: 17158943.9. Gudiol C, Albasanz-Puig A, Laporte-Amargós J, Pallarès N, Mussetti A, Ruiz-Camps I, et al. Clinical predictive model of multidrug resistance in neutropenic cancer patients with bloodstream infection due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020; 64(4):e02494–e02419. PMID: 32015035.10. Raman G, Avendano EE, Chan J, Merchant S, Puzniak L. Risk factors for hospitalized patients with resistant or multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018; 7(1):79. PMID: 29997889.11. Aliyu S, Smaldone A, Larson E. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria among nursing home residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2017; 45(5):512–518. PMID: 28456321.12. Ma HM, Wah JL, Woo J. Should nursing home-acquired pneumonia be treated as nosocomial pneumonia? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012; 13(8):727–731. PMID: 22889729.13. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200(7):e45–e67. PMID: 31573350.14. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(5):e61–111. PMID: 27418577.15. Wang HE, Shah MN, Allman RM, Kilgore M. Emergency department visits by nursing home residents in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011; 59(10):1864–1872. PMID: 22091500.16. Sung-jin CS. Korea has most nursing hospitals in OECD. Updated 2014. Accessed April 17, 2022. https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/646365.html .17. Munoz-Price LS. Long-term acute care hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 49(3):438–443. PMID: 19548836.18. Jeon K, Na SJ, Oh DK, Park S, Choi EY, Kim SC, et al. Characteristics, management and clinical outcomes of patients with sepsis: a multicenter cohort study in Korea. Acute Crit Care. 2019; 34(3):179–191. PMID: 31723927.19. Park S, Jeon K, Oh DK, Choi EY, Seong GM, Heo J, et al. Normothermia in patients with sepsis who present to emergency departments is associated with low compliance with sepsis bundles and increased in-hospital mortality rate. Crit Care Med. 2020; 48(10):1462–1470. PMID: 32931189.20. Kim E, Jeon K, Oh DK, Cho YJ, Hong SB, Lee YJ, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy in pneumonia and non-pneumonia sepsis patients: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Med. 2021; 10(16):3587. PMID: 34441886.21. Lee HY, Lee J, Jung YS, Kwon WY, Oh DK, Park MH, et al. Preexisting clinical frailty is associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2022; 50(5):780–790. PMID: 34612849.22. Yeo HJ, Lee YS, Kim TH, Jang JH, Lee HB, Oh DK, et al. Vasopressor initiation within 1 hour of fluid loading is associated with increased mortality in septic shock patients: analysis of national registry data. Crit Care Med. 2022; 50(4):e351–e360. PMID: 34612848.23. Im Y, Kang D, Ko RE, Lee YJ, Lim SY, Park S, et al. Time-to-antibiotics and clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis and septic shock: a prospective nationwide multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2022; 26(1):19. PMID: 35027073.24. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012; 18(3):268–281. PMID: 21793988.25. Southeast Asia Infectious Disease Clinical Research Network. Causes and outcomes of sepsis in southeast Asia: a multinational multicentre cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017; 5(2):e157–e167. PMID: 28104185.26. Deen J, von Seidlein L, Andersen F, Elle N, White NJ, Lubell Y. Community-acquired bacterial bloodstream infections in developing countries in south and southeast Asia: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012; 12(6):480–487. PMID: 22632186.27. Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, Ranieri VM, Reinhart K, Gerlach H, et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34(2):344–353. PMID: 16424713.28. Vincent JL, Lefrant JY, Kotfis K, Nanchal R, Martin-Loeches I, Wittebole X, et al. Comparison of European ICU patients in 2012 (ICON) versus 2002 (SOAP). Intensive Care Med. 2018; 44(3):337–344. PMID: 29450593.29. Brodská H, Malíčková K, Adámková V, Benáková H, Šťastná MM, Zima T. Significantly higher procalcitonin levels could differentiate Gram-negative sepsis from Gram-positive and fungal sepsis. Clin Exp Med. 2013; 13(3):165–170. PMID: 22644264.30. Abe R, Oda S, Sadahiro T, Nakamura M, Hirayama Y, Tateishi Y, et al. Gram-negative bacteremia induces greater magnitude of inflammatory response than Gram-positive bacteremia. Crit Care. 2010; 14(2):R27. PMID: 20202204.31. Surbatovic M, Popovic N, Vojvodic D, Milosevic I, Acimovic G, Stojicic M, et al. Cytokine profile in severe Gram-positive and Gram-negative abdominal sepsis. Sci Rep. 2015; 5(1):11355. PMID: 26079127.32. Minasyan H. Sepsis: mechanisms of bacterial injury to the patient. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019; 27(1):19. PMID: 30764843.33. De Oliveira DM, Forde BM, Kidd TJ, Harris PN, Schembri MA, Beatson SA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020; 33(3):e00181–e00119. PMID: 32404435.34. Capsoni N, Bellone P, Aliberti S, Sotgiu G, Pavanello D, Visintin B, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of patients coming from the community with sepsis due to multidrug resistant bacteria. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2019; 14(1):23. PMID: 31312449.35. Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE, Maragakis LL. Combination therapy for treatment of infections with gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012; 25(3):450–470. PMID: 22763634.36. Livermore DM. Current epidemiology and growing resistance of gram-negative pathogens. Korean J Intern Med. 2012; 27(2):128–142. PMID: 22707882.37. Yoon YK, Kwon KT, Jeong SJ, Moon C, Kim B, Kiem S, et al. Guidelines on implementing antimicrobial stewardship programs in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2021; 53(3):617–659. PMID: 34623784.38. Choi MJ, Noh JY, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ, Kim MJ, Jang YS, et al. Spread of ceftriaxone non-susceptible pneumococci in South Korea: long-term care facilities as a potential reservoir. PLoS One. 2019; 14(1):e0210520. PMID: 30699137.39. Kahn JM, Benson NM, Appleby D, Carson SS, Iwashyna TJ. Long-term acute care hospital utilization after critical illness. JAMA. 2010; 303(22):2253–2259. PMID: 20530778.40. Yoo JS, Byeon J, Yang J, Yoo JI, Chung GT, Lee YS. High prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from long-term care facilities in Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010; 67(3):261–265. PMID: 20462727.41. Jeong H, Kang S, Cho HJ. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms and risk factors for carriage among patients transferred from long-term care facilities. Infect Chemother. 2020; 52(2):183–193. PMID: 32468740.42. Choi JP, Cho EH, Lee SJ, Lee ST, Koo MS, Song YG. Influx of multidrug resistant, Gram-negative bacteria (MDRGNB) in a public hospital among elderly patients from long-term care facilities: a single-center pilot study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012; 54(2):e19–e22. PMID: 21764147.43. Jacobs Slifka KM, Kabbani S, Stone ND. Prioritizing prevention to combat multidrug resistance in nursing homes: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020; 21(1):5–7. PMID: 31888864.44. McKinnell JA, Singh RD, Miller LG, Kleinman K, Gussin G, He J, et al. The SHIELD orange county project: multidrug-resistant organism prevalence in 21 nursing homes and long-term acute care facilities in Southern California. Clin Infect Dis. 2019; 69(9):1566–1573. PMID: 30753383.45. Garnacho-Montero J, Ortiz-Leyba C, Herrera-Melero I, Aldabó-Pallás T, Cayuela-Dominguez A, Marquez-Vacaro JA, et al. Mortality and morbidity attributable to inadequate empirical antimicrobial therapy in patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis: a matched cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008; 61(2):436–441. PMID: 18056733.46. Vazquez-Guillamet C, Scolari M, Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, Kollef M. Using the number needed to treat to assess appropriate antimicrobial therapy as a determinant of outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2014; 42(11):2342–2349. PMID: 25072764.47. Cheng MP, Stenstrom R, Paquette K, Stabler SN, Akhter M, Davidson AC, et al. Blood culture results before and after antimicrobial administration in patients with severe manifestations of sepsis: a diagnostic study. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 171(8):547–554. PMID: 31525774.48. Phua J, Ngerng W, See K, Tay C, Kiong T, Lim H, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of culture-negative versus culture-positive severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2013; 17(5):R202. PMID: 24028771.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Anti-inflammatory and Anti-bacterial Effects of Aloe vera MAP against Multidrug-resistant Bacteria

- Multidrug-resistant bacteria: a national challenge requiring urgent addressal

- Sentinel Surveillance and Molecular Epidemiology of Multidrug Resistance Bacteria

- Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Positive Bacterial Infections

- Urgent need for novel antibiotics in Republic of Korea to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria