Acute Crit Care.

2023 Feb;38(1):134-141. 10.4266/acc.2022.00955.

The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography over manual aspiration for gastric reserve volume estimation in critically ill patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anaesthesia, IGMC, Shimla, India

- 2Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, PGI, Chandigarh, India

- KMID: 2540323

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/acc.2022.00955

Abstract

- Background

Although gastric reserve volume (GRV) is a surrogate marker for gastrointestinal dysfunction and feeding intolerance. There is ambiguity in its estimation in most of the international guidelines due to problems associated with its measurement. Ever since point of care ultrasound has entered into the armamentarium of anesthetists, it has kindled interest for its efficient use for this estimation.

Methods

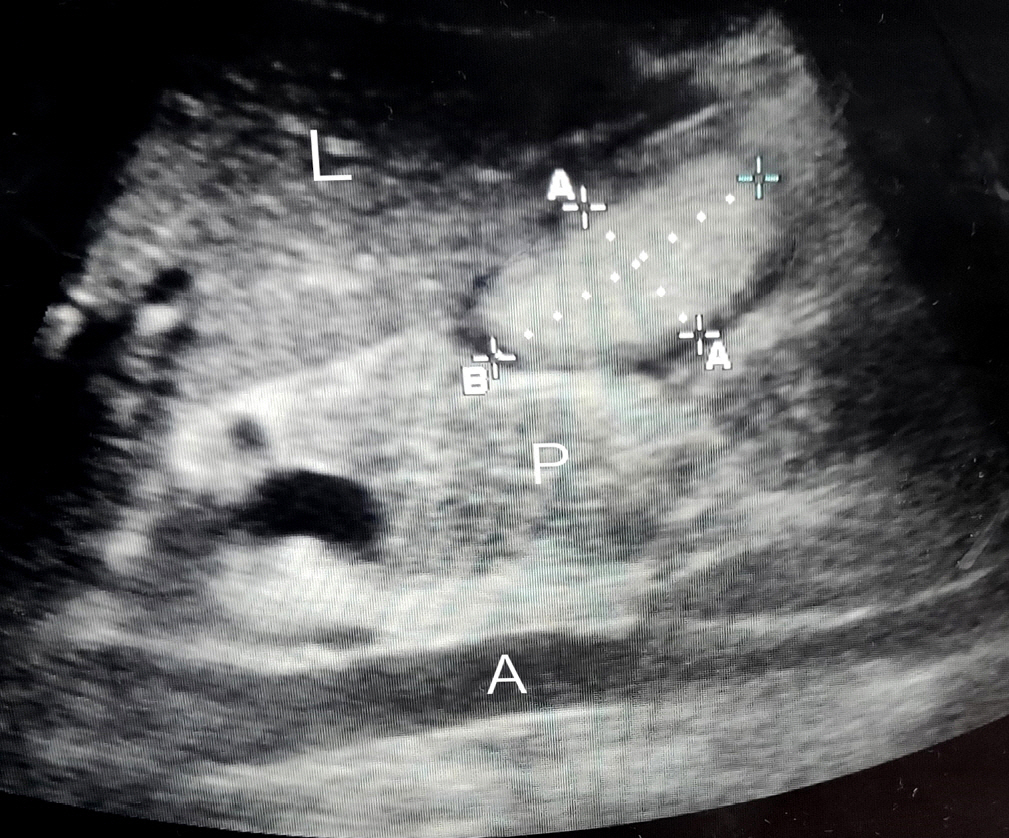

In this prospective observational study we recruited 57 critically ill patients and thus analyzed 586 samples of GRV obtained by both ultrasonographic (USG) and manual aspiration method done simultaneously on these patients.

Results

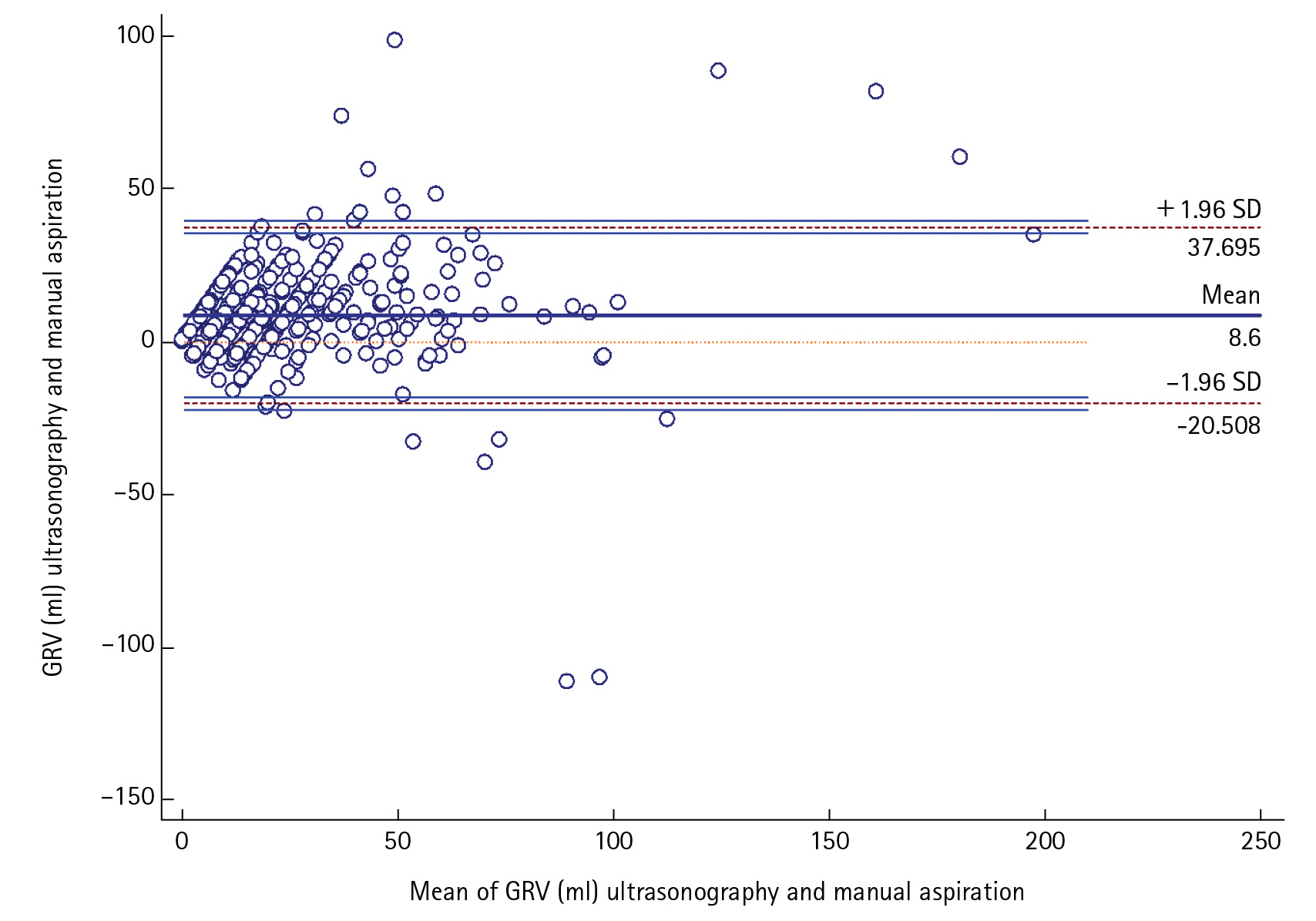

USG-guided GRV was significantly correlated (r=0.788, P<0.0001)and in positive agreement with manual aspiration technique by Bland-Altman plot with mean average of difference of 8.5±14.84 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.389–9.798) The upper and lower limit of agreement were 37.7 and –20.5 which too were within the ±1.96 standard deviation (P<0.0001).The sensitivity and positive predictive value, specificity and negative predictive value, AUC (95% CI) of the USG for finding out the feed intolerance was (66.67%, 98.15%, 0.8) in our study with 96.49% diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusions

Ultrasonographic estimation of GRV was positively, significantly correlated and was in agreement with manual aspiration method. It estimated feed intolerance earlier than manual aspiration technique. With routine use of gastric USG, its use could possibly be extrapolated in clinical situations where feeding status is unclear and there is high risk of aspiration and we hope it will eventually become a standard practice of critical care.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. MacLaren R, Kiser TH, Fish DN, Wischmeyer PE. Erythromycin vs metoclopramide for facilitating gastric emptying and tolerance to intragastric nutrition in critically ill patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008; 32:412–9.2. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016; 40:159–211.3. Gungabissoon U, Hacquoil K, Bains C, Irizarry M, Dukes G, Williamson R, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, clinical consequences, and treatment of enteral feed intolerance during critical illness. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015; 39:441–8.4. Elke G, Felbinger TW, Heyland DK. Gastric residual volume in critically ill patients: a dead marker or still alive? Nutr Clin Pract. 2015; 30:59–71.5. Perlas A, Chan VW, Lupu CM, Mitsakakis N, Hanbidge A. Ultrasound assessment of gastric content and volume. Anesthesiology. 2009; 111:82–9.6. Reignier J, Mercier E, Le Gouge A, Boulain T, Desachy A, Bellec F, et al. Effect of not monitoring residual gastric volume on risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults receiving mechanical ventilation and early enteral feeding: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013; 309:249–56.7. Reignier J, Boisramé-Helms J, Brisard L, Lascarrou JB, Ait Hssain A, Anguel N, et al. Enteral versus parenteral early nutrition in ventilated adults with shock: a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group study (NUTRIREA-2). Lancet. 2018; 391:133–43.8. Beckers EJ, Rehrer NJ, Brouns F, Ten Hoor F, Saris WH. Determination of total gastric volume, gastric secretion and residual meal using the double sampling technique of George. Gut. 1988; 29:1725–9.9. Chang WK, McClave SA, Lee MS, Chao YC. Monitoring bolus nasogastric tube feeding by the Brix value determination and residual volume measurement of gastric contents. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004; 28:105–12.10. Bartlett Ellis RJ, Fuehne J. Examination of accuracy in the assessment of gastric residual volume: a simulated, controlled study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015; 39:434–40.11. Sharma G, Jacob R, Mahankali S, Ravindra MN. Preoperative assessment of gastric contents and volume using bedside ultrasound in adult patients: a prospective, observational, correlation study. Indian J Anaesth. 2018; 62:753–8.12. Hamada SR, Garcon P, Ronot M, Kerever S, Paugam-Burtz C, Mantz J. Ultrasound assessment of gastric volume in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014; 40:965–72.13. Sharma V, Gudivada D, Gueret R, Bailitz J. Ultrasound-assessed gastric antral area correlates with aspirated tube feed volume in enterally fed critically ill patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017; 32:206–11.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Current Survey of the Gastric Residual Volume in Critically Ill Patients Who Are Receiving Enteral Nutrition

- Energy Requirements in Critically Ill Patients

- Assessment of Factors Affecting the Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography in T2 Stage Gastric Cancer

- Clinical Significance of Preoperative Studies in Diagnosis of Thyroid Nodule : FNAC, Ultrasonography, Computed Tomography

- Factors Affecting the Diagnostic Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for the Depth of Invasion in Early Gastric Cancer