J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Feb;38(6):e40. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e40.

Temporal Trends and Characteristics of Adult Patients in Emergency Department Related to Suicide Attempt or Self-Harm in Korea, 2016–2020

- Affiliations

-

- 1Public Health Research Institute, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 2National Emergency Medical Center, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul Metropolitan Government- Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2539489

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e40

Abstract

- Background

The implementation of an effective suicide prevention program requires the identification and monitoring of subpopulations with elevated risks for suicide in consideration of demographic characteristics, to facilitate the development of tailored countermeasures for tackling the risk factors of suicide. We examined the annual trends in emergency department (ED) visits for suicide attempts (SAs) or self-harm and investigated the sex- and age-specific characteristics of individuals who visited the ED for SA and self-harm.

Methods

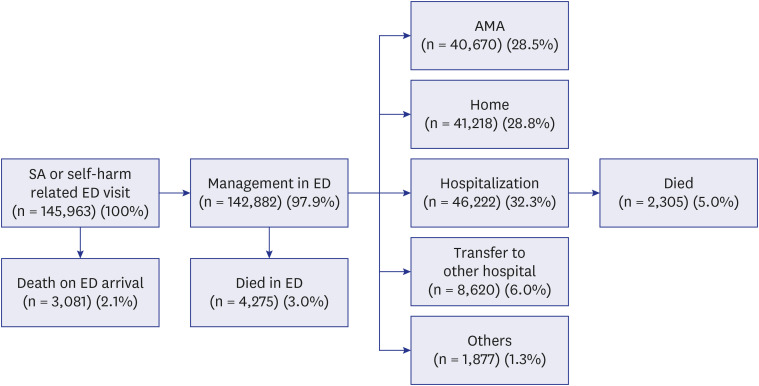

Data on ED visits for SAs or self-harm in Korea from 2016 to 2020 were extracted from the National Emergency Department Information System and assessed. We evaluated the age-standardized incidence rate of ED visits for SAs or self-harm, and hospital mortality among individuals who visited the ED for SAs or self-harm. In addition, the characteristics of the individuals were compared according to sex and age.

Results

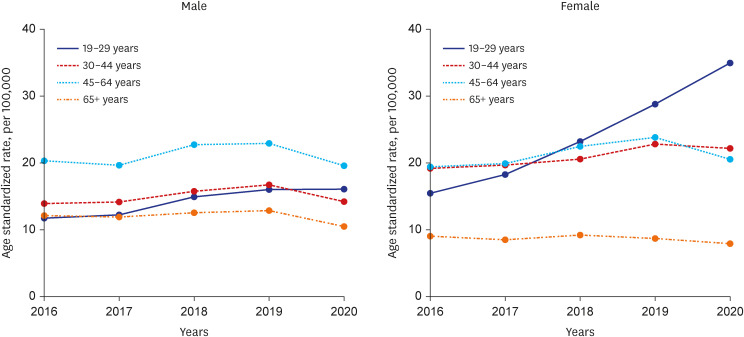

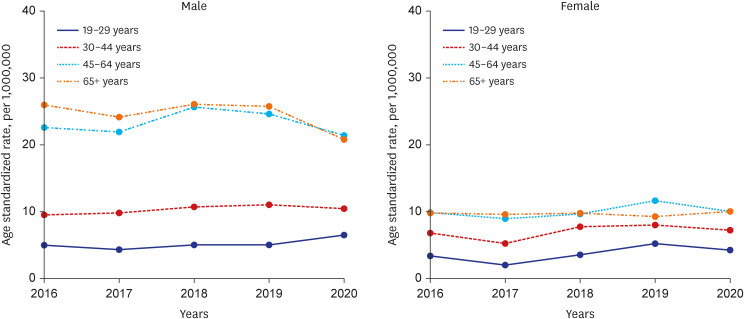

We identified 145,963 ED visits for SAs or self-harm (0.42% of the total ED visits) during the study period. The rate of ED visits increased in the youngest age group (19–29 years old), and was more prominent among women (increased by an annual average of 22.5%), despite the coronavirus disease pandemic. The middle-aged group (45–64 years old) had a higher rate of mortality than other age groups, and the highest proportion of individuals on Medical Aid.

Conclusion

It is necessary to plan age- and gender-specific suicide prevention programs that focus on improving the limited public mental health resources for the vulnerable populations.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. The World Bank. Suicide mortality rate (per 100,000 population) - OECD members. Updated 2020. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.SUIC.P5?locations=OE .2. Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, et al. Vital signs: trends in state suicide rates - United States, 1999–2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide - 27 states, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018; 67(22):617–624. PMID: 29879094.

Article3. Hawton K, Bergen H, Cooper J, Turnbull P, Waters K, Ness J, et al. Suicide following self-harm: findings from the Multicentre Study of self-harm in England, 2000–2012. J Affect Disord. 2015; 175:147–151. PMID: 25617686.

Article4. Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, Sivilotti ML, Hutson JR, Mamdani MM, et al. Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015; 72(6):570–575. PMID: 25830811.

Article5. Leon AC, Friedman RA, Sweeney JA, Brown RP, Mann JJ. Statistical issues in the identification of risk factors for suicidal behavior: the application of survival analysis. Psychiatry Res. 1990; 31(1):99–108. PMID: 2315425.

Article6. Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Sociodemographic, psychiatric and somatic risk factors for suicide: a Swedish national cohort study. Psychol Med. 2014; 44(2):279–289. PMID: 23611178.

Article7. Otaka Y, Arakawa R, Narishige R, Okubo Y, Tateno A. Suicide decline and improved psychiatric treatment status: longitudinal survey of suicides and serious suicide attempters in Tokyo. BMC Psychiatry. 2022; 22(1):221. PMID: 35351060.

Article8. Sveticic J, De Leo D. The hypothesis of a continuum in suicidality: a discussion on its validity and practical implications. Ment Illn. 2012; 4(2):e15. PMID: 25478116.

Article9. Kawashima Y, Yonemoto N, Inagaki M, Yamada M. Prevalence of suicide attempters in emergency departments in Japan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014; 163:33–39. PMID: 24836085.

Article10. Betz ME, Wintersteen M, Boudreaux ED, Brown G, Capoccia L, Currier G, et al. Reducing suicide risk: challenges and opportunities in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2016; 68(6):758–765. PMID: 27451339.

Article11. Freeman J, Strauss P, Hamilton S, Pugh C, Browne K, Caren S, et al. They told me “this isn’t a hotel”: young people’s experiences and perceptions of care when presenting to the emergency department with suicide-related behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(3):1377. PMID: 35162409.

Article12. Lewitzka U, Sauer C, Bauer M, Felber W. Are national suicide prevention programs effective? A comparison of 4 verum and 4 control countries over 30 years. BMC Psychiatry. 2019; 19(1):158. PMID: 31122215.

Article13. Sung HK, Paik JH, Lee YJ, Kang S. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on emergency care utilization in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a nationwide population-based study. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(16):e111. PMID: 33904263.

Article14. Lee KS, Lim D, Paik JW, Choi YY, Jeon J, Sung HK. Suicide attempt-related emergency department visits among adolescents: a nationwide population-based study in Korea, 2016–2019. BMC Psychiatry. 2022; 22(1):418. PMID: 35733111.

Article15. Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164(7):1035–1043. PMID: 17606655.

Article16. Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits and patient safety in the United States. Am J Emerg Med. 2020; 38(9):1732–1736. PMID: 32738468.

Article17. Pak YS, Ro YS, Kim SH, Han SH, Ko SK, Kim T, et al. Effects of emergency care-related health policies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea: a quasi-experimental study. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(16):e121. PMID: 33904264.

Article18. Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, Coletta MA, Boehmer TK, Adjemian J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits - United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(23):699–704. PMID: 32525856.

Article19. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(32):1049–1057. PMID: 32790653.

Article20. Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 301:113998. PMID: 34022657.

Article21. O’Connor RC, Wetherall K, Cleare S, McClelland H, Melson AJ, Niedzwiedz CL, et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health & wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatry. 2021; 218(6):326–333. PMID: 33081860.

Article22. Niedzwiedz CL, Green MJ, Benzeval M, Campbell D, Craig P, Demou E, et al. Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of the UK household longitudinal study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021; 75(3):224–231. PMID: 32978210.

Article23. Ueda M, Nordström R, Matsubayashi T. Suicide and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. J Public Health (Oxf). 2022; 44(3):541–548. PMID: 33855451.

Article24. Goldman-Mellor SJ, Caspi A, Harrington H, Hogan S, Nada-Raja S, Poulton R, et al. Suicide attempt in young people: a signal for long-term health care and social needs. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014; 71(2):119–127. PMID: 24306041.25. Lee J, Bang YS, Min S, Ahn JS, Kim H, Cha YS, et al. Characteristics of adolescents who visit the emergency department following suicide attempts: comparison study between adolescents and adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2019; 19(1):231. PMID: 31349782.

Article26. Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002; 181(3):193–199. PMID: 12204922.27. Christiansen E, Jensen BF. Risk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: a register-based survival analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007; 41(3):257–265. PMID: 17464707.

Article28. Yamasaki A, Sakai R, Shirakawa T. Low income, unemployment, and suicide mortality rates for middle-age persons in Japan. Psychol Rep. 2005; 96(2):337–348. PMID: 15941108.

Article29. Kim J, Yoon SY. Association between socioeconomic attainments and suicidal ideation by age groups in Korea. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018; 64(7):628–636. PMID: 30084278.

Article30. Park SM. Effects of work conditions on suicidal ideation among middle-aged adults in South Korea. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019; 65(2):144–150. PMID: 30776940.

Article31. Hempstead KA, Phillips JA. Rising suicide among adults aged 40–64 years: the role of job and financial circumstances. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 48(5):491–500. PMID: 25736978.32. Kerr WC, Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Caetano R, Giesbrecht N, McFarland BH. Economic recession, alcohol, and suicide rates: comparative effects of poverty, foreclosure, and job loss. Am J Prev Med. 2017; 52(4):469–475. PMID: 27856114.

Article33. Snowdon J, Chen YY, Zhong B, Yamauchi T. A longitudinal comparison of age patterns and rates of suicide in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan and two Western countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018; 31:15–20. PMID: 29306726.

Article34. Lee SU, Park JI, Lee S, Oh IH, Choi JM, Oh CM. Changing trends in suicide rates in South Korea from 1993 to 2016: a descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2018; 8(9):e023144.

Article35. Crane EH. Patients with drug-related emergency department visits involving suicide attempts who left against medical advice. The CBHSQ Report. Rockville, MD, USA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US);2013. p. 1–5.36. El Majzoub I, El Khuri C, Hajjar K, Bou Chebl R, Talih F, Makki M, et al. Characteristics of patients presenting post-suicide attempt to an Academic Medical Center Emergency Department in Lebanon. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018; 17(1):21. PMID: 29849740.

Article37. Kazimi M, Niforatos JD, Yax JA, Raja AS. Discharges against medical advice from U.S. emergency departments. Am J Emerg Med. 2020; 38(1):159–161. PMID: 31208842.

Article38. Brook M, Hilty DM, Liu W, Hu R, Frye MA. Discharge against medical advice from inpatient psychiatric treatment: a literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2006; 57(8):1192–1198. PMID: 16870972.

Article39. Kuo CJ, Tsai SY, Liao YT, Lee WC, Sung XW, Chen CC. Psychiatric discharge against medical advice is a risk factor for suicide but not for other causes of death. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010; 71(6):808–809. PMID: 20573333.

Article40. Kim H, Kim SG, Oh H, Choi S. Case management of suicide attempters seen in emergency rooms: result and factors affecting consent to follow-up. J Korean Soc Emerg Med. 2018; 29(2):160–169.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Comparison of suicide and self-harm characteristics before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea

- Patterns of self-harm/suicide attempters who visited emergency department over the past 10 years and changes in poisoning as a major method (2011–2020)

- Predictors of Psychiatric Outpatient Adherence after an Emergency Room Visit for a Suicide Attempt

- Suicide Related Indicators and Trends in Korea in 2020

- The Clinical Characteristics of Elderly Suicide Attempters Visiting Emergency Room