Nutr Res Pract.

2023 Feb;17(1):73-90. 10.4162/nrp.2023.17.1.73.

Ethnic differences in attitudes, beliefs, and patterns of meat consumption among American young women meat eaters

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Family, Nutrition and Exercise Sciences, Queens College, the City University of New York, Flushing, NY 11367-1597, USA

- 2Department of Food and Nutrition, Kyungnam University, Changwon 51767, Korea

- KMID: 2539454

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2023.17.1.73

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Meat eaters face conflicts over meat consumption due to recent increasing demands for reduced-meat diets to promote human and environmental health. Attitudes toward consuming meat have been shown to be culture-specific. Thus, this study was performed to examine cultural differences in attitudes, beliefs, and patterns of meat consumption among meat eaters in a group homogeneous in terms of age and sex but with diverse ethnicities.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

In this cross-sectional study conducted in New York City in 2014, 520 female meat eaters (Whites = 25%; Blacks = 20%; East Asians = 35%; Hispanics = 20%) aged 20–29 completed a questionnaire consisting of a series of questions on meat consumption behaviors, which addressed amounts of consumption, cooking methods, past and future changes in meat consumption, and attitudes and beliefs regarding relationships between health and meat consumption. Logistic and multiple regression analyses were used to assess the effects of variables on meat consumption.

RESULTS

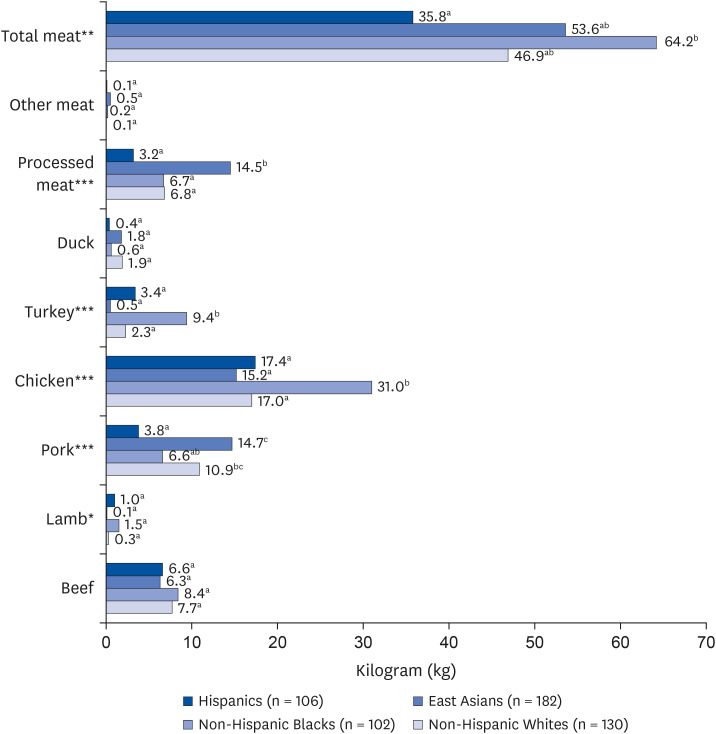

Blacks had the highest annual total meat consumption (64.2 kg), followed by East Asians (53.6 kg), Whites (46.9 kg), and Hispanics (35.8 kg). Blacks ate significantly more chicken than the other ethnic groups (P < 0.001), and East Asians ate significantly more pork and processed meat (P < 0.001). Regardless of ethnicity, grilling/roasting/broiling were the preferred cooking methods, and vegetables were most consumed as a side dish. More than half of the participants expressed an intention to decrease future meat consumption. East Asians more strongly perceived meat as a festive food (P < 0.001) and were less guilty about the slaughtering animals (P = 0.11) than other groups. No differences were found between the ethnic groups regarding negative attitudes to meat consumption.

CONCLUSIONS

The results show that ethnicities differ in terms of attitudes, beliefs, and patterns of meat consumption. Irrespective of ethnicity, the meat-eating participants almost unanimously demonstrated a willingness to reduce future meat consumption. It is hoped these findings aid the formulation of culturally-tailored interventions that effectively reduce meat consumption.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cordain L, Miller JB, Eaton SB, Mann N. Macronutrient estimations in hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 72:1589–1592. PMID: 11101497.2. Hayden B. Were luxury foods the first domesticates? Ethnoarchaeological perspectives from Southeast Asia. World Archaeol. 2003; 34:458–469.3. Psouni E, Janke A, Garwicz M. Impact of carnivory on human development and evolution revealed by a new unifying model of weaning in mammals. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e32452. PMID: 22536316.4. Becker R, Kals E, Fröhlich P. Meat consumption and commitments on meat policy: combining individual and public health. J Health Psychol. 2004; 9:143–155. PMID: 14683576.5. Ruby MB. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite. 2012; 58:141–150. PMID: 22001025.6. Rust NA, Ridding L, Ward C, Clark B, Kehoe L, Dora M, Whittingham MJ, McGowan P, Chaudhary A, Reynolds CJ, et al. How to transition to reduced-meat diets that benefit people and the planet. Sci Total Environ. 2020; 718:137208. PMID: 32088475.7. Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, Ghissassi FE, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Mattock H, Straif K. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015; 16:1599–1600. PMID: 26514947.8. Loughnan S, Haslam N, Bastian B. The role of meat consumption in the denial of moral status and mind to meat animals. Appetite. 2010; 55:156–159. PMID: 20488214.9. Friel S, Dangour AD, Garnett T, Lock K, Chalabi Z, Roberts I, Butler A, Butler CD, Waage J, McMichael AJ, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: food and agriculture. Lancet. 2009; 374:2016–2025. PMID: 19942280.10. Westhoek H, Lesschen JP, Rood T, Wagner S, De Marco A, Murphy-Bokern D, Leip A, van Grinsven H, Sutton MA, Oenema O. Food choice, health and environment: Effects of cutting Europe’s meat and dairy intake. Glob Environ Change. 2014; 26:196–205.11. OECD/FAO. “Table C.4 - World Meat Projections” in OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030. Paris: OECD Publishing;2021.12. Smil V. Eating meat: evolution, patterns, and consequences. Popul Dev Rev. 2002; 28:599–639.13. Kittler PG, Sucher KP, Nahikian-Nelms M. Food & Culture. 7th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning;2017. p. 4–10.14. Andrews M, Backstrand J, Boyle J, Campinha-Bacote J, Davidhizar RE, Doutrich D, Enchevarria M, Newman GJ, Glittenberg J, Holtz C, et al. Theoretical basis for transcultural care. J Transcult Nurs. 2010; 21(Suppl.):53S–136S.15. Sheikh N, Thomas J. Factors influencing food choice among ethnic minority adolescents. Nutr Food Sci. 1994; 94:29–35.16. Devine CM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA, Connors M. Food choice in three ethnic groups: interactions of ideals, identities, and roles. J Nutr Educ. 1999; 31:86–93.17. Dindyal S, Dindyal S. How personal factors including culture and ethnicity affect the choices and selection of food we make. Internet J Third World Med. 2003; 1:1–4.18. Heine S, Lehman D. Culture, dissomance, and self-affirmation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1997; 23:389–400.19. Kitayama S, Snibbe AC, Markus HR, Suzuki T. Is there any “free” choice? Self and dissonance in two cultures. Psychol Sci. 2004; 15:527–533. PMID: 15270997.20. Tian Q, Hilton D, Becker M. Confronting the meat paradox in different cultural contexts: reactions among Chinese and French participants. Appetite. 2016; 96:187–194. PMID: 26368579.21. Beardsworth A, Bryman A, Keil T, Goode J, Haslam C, Lancashire E. Women, men, and food. The significance of gender for nutritional attitudes and choices. Br Food J. 2002; 104:470–491.22. Prättälä R, Paalanen L, Grinberga D, Helasoja V, Kasmel A, Petkeviciene J. Gender differences in the consumption of meat, fruit and vegetables are similar in Finland and the Baltic countries. Eur J Public Health. 2007; 17:520–525. PMID: 17194710.23. Hayley A, Zinkiewicz L, Hardiman K. Values, attitudes, and frequency of meat consumption. Predicting meat-reduced diet in Australians. Appetite. 2015; 84:98–106. PMID: 25312749.24. Love HJ, Sulikowski D. Of meat and men: sex differences in implicit and explicit attitudes toward meat. Front Psychol. 2018; 9:559. PMID: 29731733.25. United States Census Bureau. 2020 Census Statistics Highlight Local Population Changes and Nation’s Racial and Ethnic Diversity. Release Number CB21-CN.55 [Internet]. Suitland (MD): United States Census Bureau;2021. cited 2021 August 21. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/population-changes-nations-diversity.html.26. Queens College. About QC [Internet]. Flushing (NY): Queens College;2021. cited 2021 September 1. Available from: https://www.qc.cuny.edu/about/Pages/default.aspx.27. Mills S, Brown H, Wrieden W, White M, Adams J. Frequency of eating home cooked meals and potential benefits for diet and health: cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017; 14:109. PMID: 28818089.28. Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986; 124:453–469. PMID: 3740045.29. Piazza J, Ruby MB, Loughnan S, Luong M, Kulik J, Watkins HM, Seigerman M. Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite. 2015; 91:114–128. PMID: 25865663.30. de Boer J, Schösler H, Aiking H. Towards a reduced meat diet: Mindset and motivation of young vegetarians, low, medium and high meat-eaters. Appetite. 2017; 113:387–397. PMID: 28300608.31. Bonne K, Verbeke W. Religious values informing halal meat production and the control and delivery of halal credence quality. Agric Human Values. 2008; 25:35–47.32. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics;2020.33. OECD. Meat Consumption (indicator) [Internet]. Paris: OECD;2021. cited 2021 July 23. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/agroutput/meat-consumption.htm.34. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Food Balance Sheets: Bovine Meat – Food Supply Quantity [Internet]. Rome: FAO;2017. cited 2021 July 31. Available from: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/?#data/.35. Adams C. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist Vegetarian Critical Theory. New York (NY): Continuum International Publishing Group;1990.36. Trocchia PJ, Janda S. A cluster analytic approach for consumer segmentation using the vegetarian/meatarian distinction. J Food Prod Mark. 2003; 9:11–23.37. Browarnik B. Attitudes Toward Male Vegetarians: Challenging Gender Norms Through Food Choices. Psychology Honors Papers. New London (CT): Connecticut College;2012.38. Santos ML, Booth DA. Influences on meat avoidance among British students. Appetite. 1996; 27:197–205. PMID: 9015557.39. Hopwood CJ, Piazza J, Chen S, Bleidorn W. Development and validation of the motivations eat meat inventory. Appetite. 2021; 163:105210. PMID: 33774135.40. Stegelin FE. Demand for meats: a comparison of ethnic groups. J Food Distrib Res. 2002; 179–181.41. USDA, Economic Research Service. US Food Commodity Availability by Foods Source, 1994–2008 [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: USDA, Economic Research Service;2016. cited 2021 August 1. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/commodity-consumption-by-population-characteristics/.42. Guenther PM, Jensen HH, Batres-Marquez SP, Chen CF. Sociodemographic, knowledge, and attitudinal factors related to meat consumption in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005; 105:1266–1274. PMID: 16182644.43. Hill K. Are Asian Diets Looking Fattier and Meatier Than Ever Before? [Internet]. New York (NY): South China Morning Post;2019. cited 2021 August 7. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/magazines/style/travel-food/article/3020071/do-asians-crave-fatty-sodium-filled-burgers-and-fried.44. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. Livestock and Poultry: World Market and Trade [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service;2021. cited 2021 August 31. Available from: http://www.fas.usda.gov/data/livestock-and-poultry-world-markets-and-trade.45. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Volume 114: consumption of red meat and processed meat. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. Lyon: IARC Working Group;2015.46. Kim EM, Seo SH, Lee MA, Kwon KH, Jun GH. Preferences and consumption patterns of general consumers of meat dishes. J Korean Soc Food Cult. 2010; 25:251–261.47. Bai YH, Hwang DH. A study on the dining-out preference and behavior of consumers for the chilled meat consumption strategy in Seoul-Kyunggi area. J Korean Soc Food Cult. 1997; 13:169–182.48. Lee K, Cho M. Bulgogi: Cultural History of Korean Meat Grilling. Seoul: Tabibooks;2021. p. 317–322.49. Yoon GS, Woo JW. The perception and the consumption behavior for the meats in Koreans. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 1999; 28:246–256.50. Lea E, Worsley A. Influences on meat consumption in Australia. Appetite. 2001; 36:127–136. PMID: 11237348.51. González N, Marquès M, Nadal M, Domingo JL. Meat consumption: Which are the current global risks? A review of recent (2010–2020) evidences. Food Res Int. 2020; 137:109341. PMID: 33233049.52. Godfray HC, Aveyard P, Garnett T, Hall JW, Key TJ, Lorimer J, Pierrehumbert RT, Scarborough P, Springmann M, Jebb SA. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science. 2018; 361:eaam5324. PMID: 30026199.53. US News. US News Best Diets: How We Rated 39 Eating Plans [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: US News;2021. cited 2021 August 25. Available from: https://health.usnews.com/wellness/food/articles/how-us-news-ranks-best-diets.54. Blank C. Pescetarianism Is a Fast-Growing Trend to Watch [Internet]. Portland (ME): Seafood Source News;2016. cited 2021 September 10. Available from: https://www.seafoodsource.com/news/foodservice-retail/pescetarianism-a-fast-growing-trend-to-watch.55. Diehl M, Coyle N, Labouvie-Vief G. Age and sex differences in strategies of coping and defense across the life span. Psychol Aging. 1996; 11:127–139. PMID: 8726378.56. Labouvie-Vief G, Hakim-Larson J, DeVoe M, Schoeberlein S. Emotions and self-regulation: a life span view. Hum Dev. 1989; 32:279–299.57. Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Woolard J, Graham S, Banich M. Are adolescents less mature than adults?: minors’ access to abortion, the juvenile death penalty, and the alleged APA “flip-flop”. Am Psychol. 2009; 64:583–594. PMID: 19824745.58. Joy M. Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows. An Introduction to Carnism. San Francisco (CA): Red Wheel/Weiser;2010. p. 96.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Attitude of dietitians working for elementary schools on meat products

- Association Between Meat Consumption and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Korean Adults with Metabolic Syndrome

- Intake Trends of Red Meat, Alcohol, and Fruits and Vegetables as Cancer-Related Dietary Factors from 1998 to 2009

- A combination of red and processed meat intake and polygenic risk score influences the incidence of hyperuricemia in middle-aged Korean adults

- The Consumption, Perception, and Sensory Evaluation of Soy M