J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Dec;37(48):e334. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e334.

Delayed Presentation of Spontaneous Shockable Rhythm After Death: Another Subtype of Lazarus Phenomenon?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Dankook University Hospital, College of Medicine, Dankook University, Cheonan, Korea

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon, Korea

- KMID: 2536730

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e334

Abstract

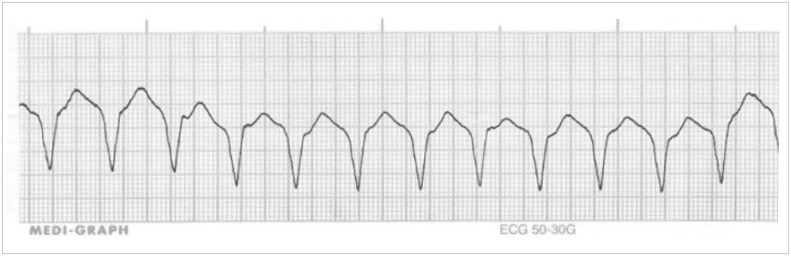

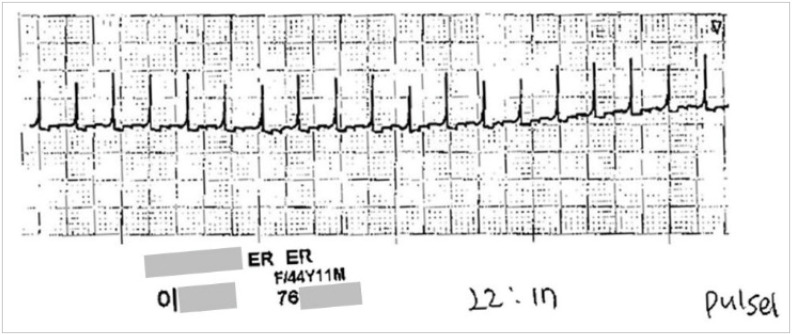

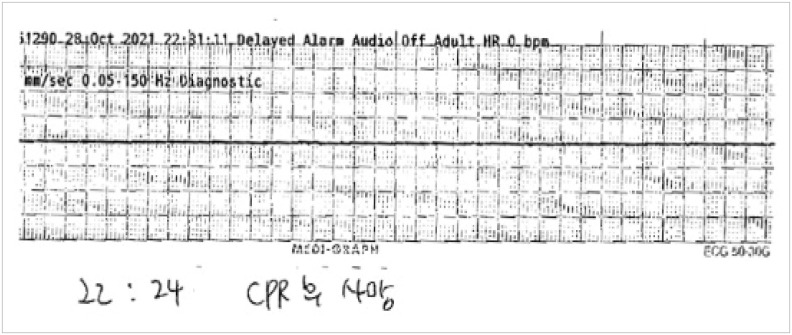

- Lazarus phenomenon was defined as spontaneous circulatory restoration after death. It is important because survival discharge is possible. A 44-year-old woman developed traumatic cardiac arrest. She was declared dead after 30 minutes of resuscitation. Suddenly, pulseless ventricular tachycardia was shown after 6 minutes of death declaration. Resuscitation with epinephrine injection was resumed but was terminated after 7 minutes, and she was declared dead once more. A case where an electrocardiography appears spontaneously should be classified as a subtype of the Lazarus phenomenon. If the transition from asystole to spontaneous shockable rhythm follows a mechanism similar to that of the Lazarus phenomenon, active resuscitation and monitoring for a period of time following death declaration should be considered.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Letellier N, Coulomb F, Lebec C, Brunet JM. Recovery after discontinued cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Lancet. 1982; 1(8279):1019.2. Gamboa E, Bronsther O, Halasz N. The Lazarus phenomenon. Clin Transpl. 1986; 125–127. PMID: 3154376.3. Gordon L, Pasquier M, Brugger H, Paal P. Autoresuscitation (Lazarus phenomenon) after termination of cardiopulmonary resuscitation - a scoping review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2020; 28(1):14. PMID: 32102671.4. Daou O, Winiszewski H, Besch G, Pili-Floury S, Belon F, Guillon B, et al. Initial pH and shockable rhythm are associated with favorable neurological outcome in cardiac arrest patients resuscitated with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Thorac Dis. 2020; 12(3):849–857. PMID: 32274152.5. Escutnaire J, Genin M, Babykina E, Dumont C, Javaudin F, Baert V, et al. Traumatic cardiac arrest is associated with lower survival rate vs. medical cardiac arrest - results from the French national registry. Resuscitation. 2018; 131:48–54. PMID: 30059713.6. Ekmektzoglou KA, Koudouna E, Bassiakou E, Stroumpoulis K, Clouva-Molyvdas P, Troupis G, et al. An intraoperative case of spontaneous restoration of circulation from asystole: a case of lazarus phenomenon. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2012; 2012:380905. PMID: 23326710.7. Mahon T, Kalakoti P, Conrad SA, Samra NS, Edens MA. Lazarus phenomenon in trauma. Trauma Case Rep. 2020; 25:100280. PMID: 31921960.8. Bäcker H, Kyburz A, Bosshard A, Babst R, Beeres FJ. Dead or dying? Pulseless electrical activity during trauma resuscitation. Br J Anaesth. 2017; 118(5):809. PMID: 28510749.9. Maeda H, Fujita MQ, Zhu BL, Yukioka H, Shindo M, Quan L, et al. Death following spontaneous recovery from cardiopulmonary arrest in a hospital mortuary: ‘Lazarus phenomenon’ in a case of alleged medical negligence. Forensic Sci Int. 2002; 127(1-2):82–87. PMID: 12098530.10. Kuisma M, Salo A, Puolakka J, Nurmi J, Kirves H, Väyrynen T, et al. Delayed return of spontaneous circulation (the Lazarus phenomenon) after cessation of out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2017; 118:107–111. PMID: 28750883.11. Sahni V. The Lazarus phenomenon. JRSM Open. 2016; 7(8):2054270416653523. PMID: 27540490.12. Olasveengen TM, Samdal M, Steen PA, Wik L, Sunde K. Progressing from initial non-shockable rhythms to a shockable rhythm is associated with improved outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2009; 80(1):24–29. PMID: 19081664.13. Zhang W, Luo S, Yang D, Zhang Y, Liao J, Gu L, et al. Conversion from nonshockable to shockable rhythms and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes by initial heart rhythm and rhythm conversion time. Cardiol Res Pract. 2020; 2020:3786408. PMID: 32300483.14. Wind J, van Mook WN, Dhanani S, van Heurn EW. Determination of death after circulatory arrest by intensive care physicians: a survey of current practice in the Netherlands. J Crit Care. 2016; 31(1):2–6. PMID: 26431638.15. Dhanani S, Ward R, Hornby L, Barrowman NJ, Hornby K, Shemie SD, et al. Survey of determination of death after cardiac arrest by intensive care physicians. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40(5):1449–1455. PMID: 22430244.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Chronic Brain-Dead Patients Who Exhibit Lazarus Sign

- St. Lazarus and Hansen's disease.

- The Frequency of Defibrillation Related to the Survival Rate and Neurological Outcome in Patients Surviving from Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Targeted temperature management is related to improved clinical outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with non-shockable initial rhythm

- Association between the platelet-to-hemoglobin ratio and survival-to-discharge in comatose patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with an initial shockable rhythm: a retrospective cohort study