Arch Hand Microsurg.

2022 Dec;27(4):329-335. 10.12790/ahm.22.0052.

Surgical outcomes of split-thickness skin grafts versus free flaps of the lateral thoracic region for incurable chronic venous ulcers

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2536221

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12790/ahm.22.0052

Abstract

- Purpose

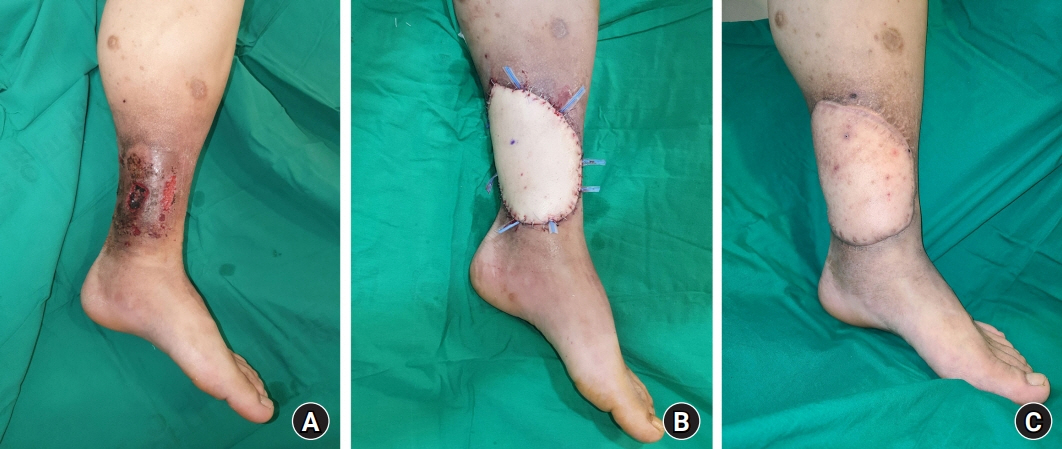

This study conducted a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) and free flaps of the lateral thoracic region performed for coverage after extensive debridement in patients with difficult-to-treat chronic venous ulcers (CVUs) with severe symptoms.

Methods

This retrospective, single-center study included 20 patients (28 cases) with CVUs. Patients who received an STSG or free-flap procedure were included in the study. Data comparing these two groups were analyzed.

Results

The STSG and free-flap groups showed no significant differences in patient demographics. There was no significant difference in wound size before and after debridement between the two groups (before, 52.25±58.03 cm2 vs. 37.69±32.83 cm2, p=0.407; after, 210.92±202.80 cm2 vs. 142.63±84.01 cm2, p=0.291). Wound disruption was not significantly different between the groups (p=0.231). However, a significant difference was found in recurrence between the STSG group (n=7, 58.3%) and the free-flap group (n=1, 6.3%) (p=0.004).

Conclusion

Free-flap surgery may be a good option for difficult-to-treat, recurrent CVU. Because venous ulcers require extensive debridement, a lateral thoracic region free flap, which enables the harvest of large and various forms of flaps, could be the best choice for microsurgery.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Bonkemeyer Millan S, Gan R, Townsend PE. Venous ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2019; 100:298–305.2. Böhler K. [Venous ulcer]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016; 166:287–92. German.3. Gould LJ, Dosi G, Couch K, et al. Modalities to treat venous ulcers: compression, surgery, and bioengineered tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016; 138(3 Suppl):199S–208S.4. Song MS, Baldwin AJ, Wormald JC, Coleman C, Chan JK. Outcomes of free flap reconstruction for chronic venous ulceration in the lower limb: a systematic review. Ann Plast Surg. 2022; 89:331–5.

Article5. Health Quality Ontario. Compression stockings for the prevention of venous leg ulcer recurrence: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2019; 19:1–86.6. Aleksandrowicz H, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W. Venous leg ulcers: advanced therapies and new technologies. Biomedicines. 2021; 9:1569.

Article7. Bitsch M, Saunte DM, Lohmann M, Holstein PE, Jørgensen B, Gottrup F. Standardised method of surgical treatment of chronic leg ulcers. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2005; 39:162–9.

Article8. Turczynski R, Tarpila E. Treatment of leg ulcers with split skin grafts: early and late results. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1999; 33:301–5.

Article9. Abisi S, Tan J, Burnand KG. Excision and meshed skin grafting for leg ulcers resistant to compression therapy. Br J Surg. 2007; 94:194–7.

Article10. Kumins NH, Weinzweig N, Schuler JJ. Free tissue transfer provides durable treatment for large nonhealing venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2000; 32:848–54.

Article11. Isenberg JS. Additional follow-up with microvascular transfer in the treatment of chronic venous stasis ulcers. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2001; 17:603–5.

Article12. Pihlaja T, Torro P, Ohtonen P, Romsi P, Pokela M. Ten years of experience with first-visit foam sclerotherapy to initiate venous ulcer healing. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021; 9:954–60.

Article13. Us MH, Ugur M. Has external banding become a historical technique during venous valve repair? Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2021; 67:1676–80.

Article14. Coleridge-Smith PD. Leg ulcer treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2009; 49:804–8.

Article15. Tark KC, Chung S. Histologic change of arteriovenous malformations of the face and scalp after free flap transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 106:87–93.

Article16. Steffe TJ, Caffee HH. Long-term results following free tissue transfer for venous stasis ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 1998; 41:131–9.

Article17. Watson JS, Craig RD, Orton CI. The free latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979; 64:299–305.

Article18. Kozusko SD, Liu X, Riccio CA, et al. Selecting a free flap for soft tissue coverage in lower extremity reconstruction. Injury. 2019; 50 Suppl 5:S32–9.

Article19. Irthum C, Fossat S, Bey E, Duhamel P, Braye F, Mojallal A. [Anterolateral thigh flap for distal lower leg reconstruction]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2017; 62:224–31. French.20. Yamamoto T, Saito T, Ishiura R, Iida T. Quadruple-component superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap: a chimeric SCIP flap for complex ankle reconstruction of an exposed artificial joint after total ankle arthroplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016; 69:1260–5.

Article21. Vranckx JJ, Misselyn D, Fabre G, Verhelle N, Heymans O, Van den hof B. The gracilis free muscle flap is more than just a “graceful” flap for lower-leg reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2004; 20:143–8.

Article22. Guerra AB, Metzinger SE, Lund KM, Cooper MM, Allen RJ, Dupin CL. The thoracodorsal artery perforator flap: clinical experience and anatomic study with emphasis on harvest techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114:32–43.

Article23. Ciudad P, Manrique OJ, Bustos SS, et al. The modified extended fleur-de-lis latissimus dorsi flap for various complex multi-directional large soft and bone tissue reconstruction. Cureus. 2020; 12:e6974.

Article24. Mahajan RK, Srinivasan K, Bhamre A, Singh M, Kumar P, Tambotra A. A retrospective analysis of latissimus dorsi-serratus anterior chimeric flap reconstruction in 47 patients with extensive lower extremity trauma. Indian J Plast Surg. 2018; 51:24–32.

Article25. Tachi M, Toriyabe S, Imai Y, Takeda A, Hirabayashi S, Sekiguchi J. Versatility of chimeric flap based on thoracodorsal vessels incorporating vascularized scapular bone and latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap in reconstructing lower-extremity bone defects due to osteomyelitis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2010; 26:417–24.

Article26. Ren SY, Liu YS, Zhu GJ, et al. Strategies and challenges in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers. World J Clin Cases. 2020; 8:5070–85.

Article27. Robson MC, Cooper DM, Aslam R, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of venous ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2006; 14:649–62.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Tissue transfer techniques in reconstructive urology

- Comparison of local flaps versus skin grafts as reconstruction methods for defects in the medial canthal region

- Neurovascular Free Flap Transfer by Microsurgery

- Tissue Recycling with Split-Thickness Skin Graft Harvested from a Failed Free Flap

- Surgical Treatment of Dermatomal Capillary Malformations in the Adult Face