J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Nov;37(45):e324. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e324.

Beta-Lactam Plus Macrolide for Patients Hospitalized With CommunityAcquired Pneumonia: Difference Between Autumn and Spring

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 2Department of Statistics, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University Chilgok Hospital, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 4Department of Medical Informatics, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea

- 5Quality Assessment Department, HIRA (Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service), Wonju, Korea

- KMID: 2536129

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e324

Abstract

- Background

The 2017 Korean guideline on community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) recommended beta-lactam plus macrolide combination therapy for patients hospitalized with severe pneumonia, and beta-lactam monotherapy for mild-to-moderate pneumonia. However, antibiotic treatment regimen for mild-to-moderate CAP has never been evaluated for Korean patients.

Methods

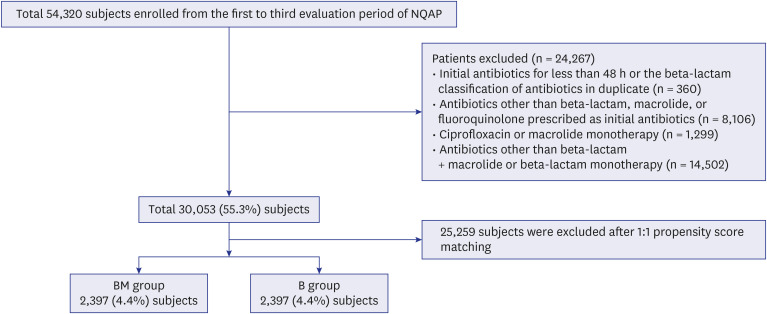

In this retrospective cohort study, study patients were selected from three evaluation periods (October 1 to December 31, 2014; April 1 to June 30, 2016; October 1 to December 31, 2017) of the National Quality Assessment Program for CAP management and the National Health Insurance data on the selected patients was extracted from 1 year before the first patient enrollment and 1 year after the last patient enrollment at each evaluation period for the analysis of risk adjustment and outcomes. The survival rates between beta-lactam plus macrolide (BM) groups and beta-lactam monotherapy (B) were compared using a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis after propensity score matching by age, gender, confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure at age of 65 years or older (CURB-65), and Charlson comorbidity index for risk adjustment. The differences between autumn and spring season were also evaluated.

Results

A total of 30,053 patients were enrolled. Mean age and the male-to-female ratio were 64.7 ± 18.4 and 14,197:15,856, respectively. After matching, 2,397 patients in each group were analyzed. The 30-day survival rates did not differ between the BM and B groups (97.3% vs. 96.5%, P = 0.081). In patients with CURB-65 ≥ 2, the 30-day survival rate was higher in the BM than in the B group (93.7% vs. 91.0%, P = 0.044). Among patients with CURB-65 ≥ 2, the 30-day survival rate was higher in the BM than in the B group (93.3% vs. 88.5%, P = 0.009) during autumn season, which was not observed during spring (94.2% vs. 94.1%, P = 0.986).

Conclusion

Beta-lactam plus macrolide combination therapy shows potential as an empirical therapy for CAP with CURB-65 ≥ 2, especially in autumn.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lee JH, Kim HJ, Kim YH. Is β-lactam plus macrolide more effective than β-lactam plus fluoroquinolone among patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia?: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(1):77–84. PMID: 27914135.2. Statistics Korea. Causes of Death Statistics in 2019. Daejeon, Korea: Statistics Korea;2020.3. Jang SN, Kim DH. Trends in the health status of older Koreans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010; 58(3):592–598. PMID: 20398125.4. Yoon HK. Changes in the epidemiology and burden of community-acquired pneumonia in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2014; 29(6):735–737. PMID: 25378971.5. Lee JS, Giesler DL, Gellad WF, Fine MJ. Antibiotic therapy for adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review. JAMA. 2016; 315(6):593–602. PMID: 26864413.6. Kim B, Myung R, Lee MJ, Kim J, Pai H. Trend of antibiotic usage for hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia cases in Korea based on the 2010–2015 National Health Insurance data. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(47):e390. PMID: 33289366.7. Lee MS, Oh JY, Kang CI, Kim ES, Park S, Rhee CK, et al. Guideline for antibiotic use in adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Infect Chemother. 2018; 50(2):160–198. PMID: 29968985.8. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200(7):e45–e67. PMID: 31573350.9. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Pneumonia (community-acquired): antimicrobial prescribing (NG138). Updated 2019. Accessed May 8, 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng138 .10. Song JH, Jung KS, Kang MW, Kim DJ, Pai H, Suh GY, et al. Treatment guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in Korea: an evidence-based approach to appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Infect Chemother. 2009; 41(3):133–153.11. Garin N, Genné D, Carballo S, Chuard C, Eich G, Hugli O, et al. β-Lactam monotherapy vs β-lactam-macrolide combination treatment in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174(12):1894–1901. PMID: 25286173.12. Nie W, Li B, Xiu Q. β-Lactam/macrolide dual therapy versus β-lactam monotherapy for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014; 69(6):1441–1446. PMID: 24535276.13. Kim JA, Yoon S, Kim LY, Kim DS. Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) data as a resource for health research: strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(5):718–728. PMID: 28378543.14. Aljunid SM, Srithamrongsawat S, Chen W, Bae SJ, Pwu RF, Ikeda S, et al. Health-care data collecting, sharing, and using in Thailand, China mainland, South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Malaysia. Value Health. 2012; 15(1):Suppl. S132–S138. PMID: 22265060.15. Kim BY. Performance and challenges in implementing the national quality assessment program. HIRA Research. 2021; 1(1):23–30.16. Nazik S, Köktürk N, Baha A, Ekim N. CURB 65 or CURB (S) 65 for community acquired pneumonia? Eur Respir J. 2012; 40(Suppl 56):2494.17. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987; 40(5):373–383. PMID: 3558716.18. Waites KB, Ratliff A, Crabb DM, Xiao L, Qin X, Selvarangan R, et al. Macrolide-resistant mycoplasma pneumoniae in the United States as determined from a national surveillance program. J Clin Microbiol. 2019; 57(11):e00968–e00919. PMID: 31484701.19. Zheng X, Lee S, Selvarangan R, Qin X, Tang YW, Stiles J, et al. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21(8):1470–1472. PMID: 26196107.20. Pereyre S, Goret J, Bébéar C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: current knowledge on macrolide resistance and treatment. Front Microbiol. 2016; 7:974. PMID: 27446015.21. Lee HY, Choi SH, Chang J, Kim MN, Yu J, Sung H. Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae in South Korea: a strong association with M. pneumoniae type 1. Epidemiol Infect. 2019; 147:e309.22. Niederman MS. Macrolide-resistant pneumococcus in community-acquired pneumonia. Is there still a role for macrolide therapy? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 191(11):1216–1217. PMID: 26029831.23. Eliakim-Raz N, Robenshtok E, Shefet D, Gafter-Gvili A, Vidal L, Paul M, et al. Empiric antibiotic coverage of atypical pathogens for community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 2012(9):CD004418. PMID: 22972070.24. Ito A, Ishida T, Tachibana H, Tokumasu H, Yamazaki A, Washio Y. Azithromycin combination therapy for community-acquired pneumonia: propensity score analysis. Sci Rep. 2019; 9(1):18406. PMID: 31804572.25. Kovaleva A, Remmelts HH, Rijkers GT, Hoepelman AI, Biesma DH, Oosterheert JJ. Immunomodulatory effects of macrolides during community-acquired pneumonia: a literature review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012; 67(3):530–540. PMID: 22190609.26. Emmet O’Brien M, Restrepo MI, Martin-Loeches I. Update on the combination effect of macrolide antibiotics in community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Investig. 2015; 53(5):201–209.27. Rodrigo C, Mckeever TM, Woodhead M, Lim WS. British Thoracic Society. Single versus combination antibiotic therapy in adults hospitalised with community acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2013; 68(5):493–495. PMID: 23076390.28. Brown RB, Iannini P, Gross P, Kunkel M. Impact of initial antibiotic choice on clinical outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia: analysis of a hospital claims-made database. Chest. 2003; 123(5):1503–1511. PMID: 12740267.29. Lee E, Kim CH, Lee YJ, Kim HB, Kim BS, Kim HY, et al. Annual and seasonal patterns in etiologies of pediatric community-acquired pneumonia due to respiratory viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae requiring hospitalization in South Korea. BMC Infect Dis. 2020; 20(1):132. PMID: 32050912.30. Wang X, Zhang H, Zhang T, Pan L, Dong K, Yang M, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospital admission in adults with and without cancers: a single-center retrospective study in China. Infect Drug Resist. 2020; 13:1607–1617. PMID: 32606812.31. Lieberman D, Lieberman D, Porath A. Seasonal variation in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1996; 9(12):2630–2634. PMID: 8980980.32. Raeven VM, Spoorenberg SM, Boersma WG, van de Garde EM, Cannegieter SC, Voorn GP, et al. Atypical aetiology in patients hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia is associated with age, gender and season; a data-analysis on four Dutch cohorts. BMC Infect Dis. 2016; 16(1):299. PMID: 27317257.33. Uddin M, Mohammed T, Metersky M, Anzueto A, Alvarez CA, Mortensen EM. Effectiveness of beta-lactam plus doxycycline for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2022; 75(1):118–124. PMID: 34751745.34. Ota K, Iida R, Ota K, Sakaue M, Taniguchi K, Tomioka M, et al. An atypical case of atypical pneumonia. J Gen Fam Med. 2018; 19(4):133–135. PMID: 29998043.35. Lee HW, Cho PY, Moon SU, Na BK, Kang YJ, Sohn Y, et al. Current situation of scrub typhus in South Korea from 2001–2013. Parasit Vectors. 2015; 8(1):238. PMID: 25928653.36. Paris DH, Shelite TR, Day NP, Walker DH. Unresolved problems related to scrub typhus: a seriously neglected life-threatening disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013; 89(2):301–307. PMID: 23926142.37. Sethuraman VK, Balasubramanian K. An unusual clinical presentation of scrub typhus. Cureus. 2019; 11(9):e5568. PMID: 31695987.38. Kashyap S, Solanki A. Pulmonary manifestations of scrub typhus: wisdom may prevail obstacles. J Pulm Respir Med. 2015; 5(251):2.39. Song SW, Kim KT, Ku YM, Park SH, Kim YS, Lee DG, et al. Clinical role of interstitial pneumonia in patients with scrub typhus: a possible marker of disease severity. J Korean Med Sci. 2004; 19(5):668–673. PMID: 15483341.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Community Acquired Pneumonia

- Current perspectives on atypical pneumonia in children

- Comparison of the characteristics of macrolide-sensitive and macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia requiring hospitalization in children

- Is β-Lactam Plus Macrolide More Effective than β-Lactam Plus Fluoroquinolone among Patients with Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia?: a Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Antibiotic Resistance and Treatment Update of Community-Acquired Pneumonia