Acute Crit Care.

2022 Aug;37(3):382-390. 10.4266/acc.2022.00220.

Effect of a nutritional support protocol on enteral nutrition and clinical outcomes of critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Nutritional Support Team, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- KMID: 2535302

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4266/acc.2022.00220

Abstract

- Background

Enteral nutrition (EN) supply within 48 hours after intensive care unit (ICU) admission improves clinical outcomes. The “new ICU evaluation & development of nutritional support protocol (NICE-NST)” was introduced in an ICU of tertiary academic hospital. This study showed that early EN through protocolized nutritional support would supply more nutrition to improve clinical outcomes.

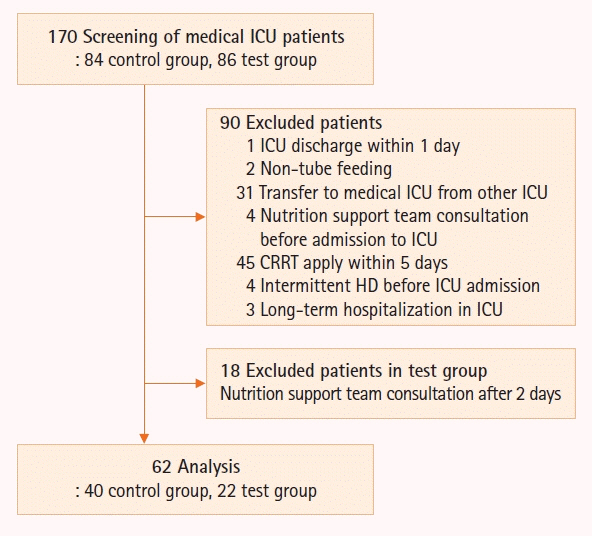

Methods

This study screened 170 patients and 62 patients were finally enrolled; patients who were supplied nutrition without the protocol were classified as the control group (n=40), while those who were supplied according to the protocol were classified as the test group (n=22).

Results

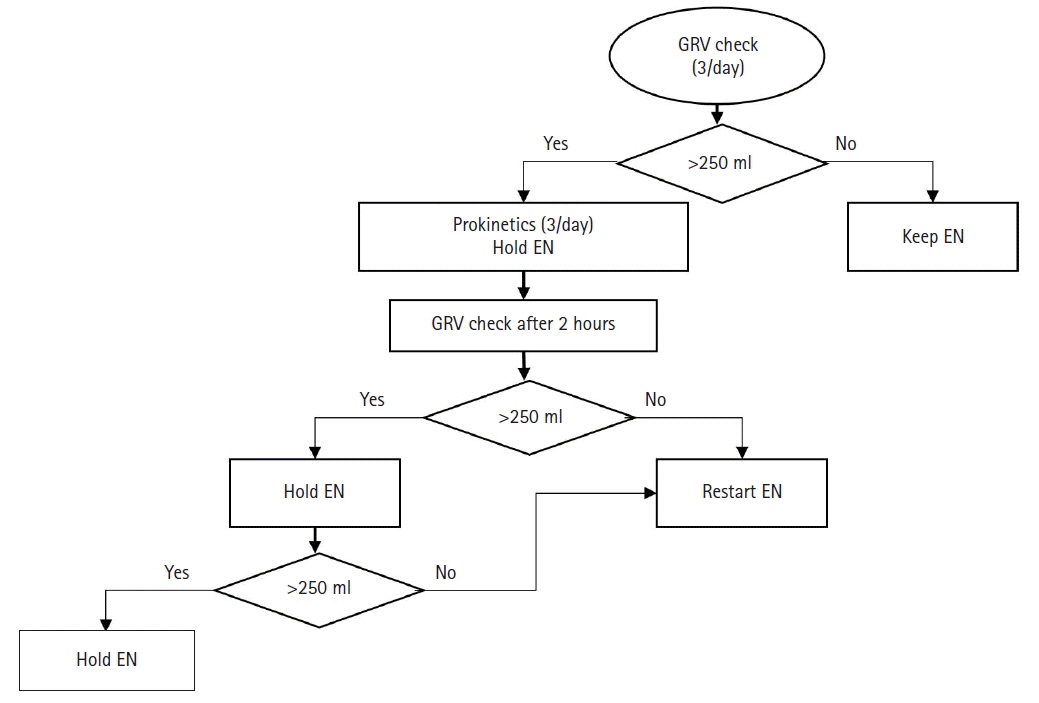

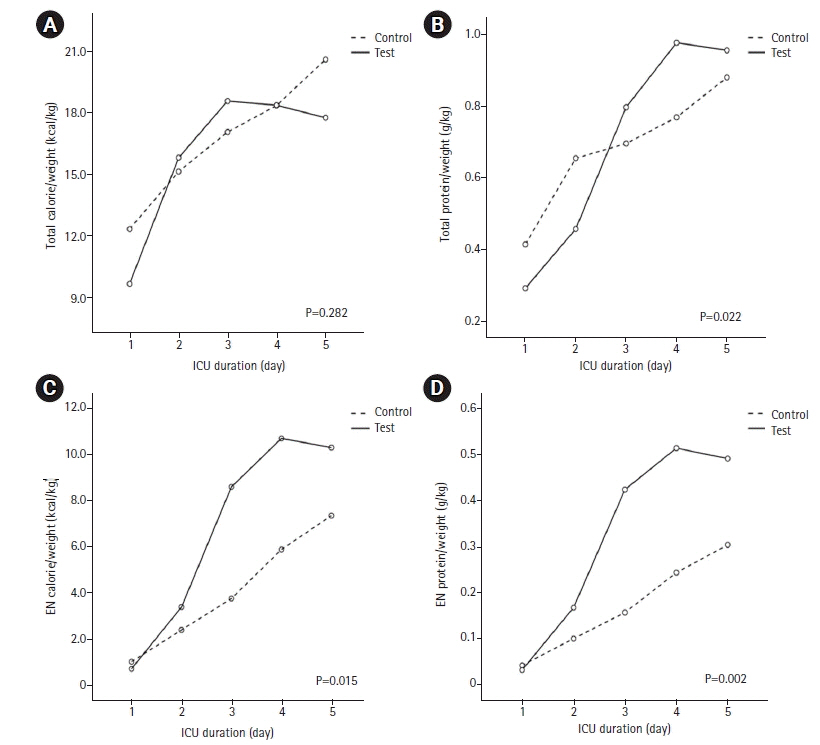

In the test group, EN started significantly earlier (3.7±0.4 days vs. 2.4±0.5 days, P=0.010). EN calorie (4.0±1.0 kcal/kg vs. 6.7±0.9 kcal/kg, P=0.006) and protein (0.17±0.04 g/kg vs. 0.32±0.04 g/kg, P=0.002) supplied were significantly higher in the test group. Although EN was supplied through continuous feeding in the test group, there was no difference in complications such as feeding hold due to excessive gastric residual volume or vomit, and hyper- or hypo-glycemia between the two groups. Hospital mortality was significantly lower in the group that started EN within 1.5 days (42.9% vs. 11.8%, P=0.018). The proportion of patients who started EN within 1.5 days was higher in the test group (40.9% vs. 17.5%, P=0.044).

Conclusions

The NICE-NST may improve EN supply and mortality of critically ill patients without increasing complications.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kreymann KG, Berger MM, Deutz NE, Hiesmayr M, Jolliet P, Kazandjiev G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr. 2006; 25:210–23.

Article2. Dhaliwal R, Cahill N, Lemieux M, Heyland DK. The Canadian critical care nutrition guidelines in 2013: an update on current recommendations and implementation strategies. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014; 29:29–43.

Article3. Preiser JC, van Zanten AR, Berger MM, Biolo G, Casaer MP, Doig GS, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care. 2015; 19:35.

Article4. Taylor BE, McClave SA, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). Crit Care Med. 2016; 44:390–438.

Article5. Arabi YM, Casaer MP, Chapman M, Heyland DK, Ichai C, Marik PE, et al. The intensive care medicine research agenda in nutrition and metabolism. Intensive Care Med. 2017; 43:1239–56.

Article6. Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer MP, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019; 38:48–79.

Article7. Braga M, Gianotti L, Gentilini O, Parisi V, Salis C, Di Carlo V. Early postoperative enteral nutrition improves gut oxygenation and reduces costs compared with total parenteral nutrition. Crit Care Med. 2001; 29:242–8.

Article8. Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Early enteral nutrition in acutely ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2001; 29:2264–70.

Article9. Kudsk KA. Current aspects of mucosal immunology and its influence by nutrition. Am J Surg. 2002; 183:390–8.

Article10. Gramlich L, Kichian K, Pinilla J, Rodych NJ, Dhaliwal R, Heyland DK. Does enteral nutrition compared to parenteral nutrition result in better outcomes in critically ill adult patients?: a systematic review of the literature. Nutrition. 2004; 20:843–8.

Article11. Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Meta-analysis of parenteral nutrition versus enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2004; 328:1407.

Article12. Artinian V, Krayem H, DiGiovine B. Effects of early enteral feeding on the outcome of critically ill mechanically ventilated medical patients. Chest. 2006; 129:960–7.

Article13. Kang W, Kudsk KA. Is there evidence that the gut contributes to mucosal immunity in humans? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007; 31:246–58.

Article14. Doig GS, Heighes PT, Simpson F, Sweetman EA, Davies AR. Early enteral nutrition, provided within 24 h of injury or intensive care unit admission, significantly reduces mortality in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Intensive Care Med. 2009; 35:2018–27.

Article15. Khalid I, Doshi P, DiGiovine B. Early enteral nutrition and outcomes of critically ill patients treated with vasopressors and mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2010; 19:261–8.

Article16. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Steingrub J, Hite RD, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012; 307:795–803.

Article17. Marik PE, Hooper MH. Normocaloric versus hypocaloric feeding on the outcomes of ICU patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016; 42:316–23.

Article18. Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Jiang X, Day AG. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: the development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Crit Care. 2011; 15:R268.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Nutritional Support in Critically Ill Surgical Patients

- The Outcomes of Critically Ill Patients after Following the Recommendations of the Nutritional Support Team

- Nutritional Intake and Timing of Initial Enteral Nutrition in Intensive Care Patients: A Pilot Study

- Nutritional Support in the Critically Ill Patient

- Nutrition Therapy in Critically Ill Patients