J Korean Soc Matern Child Health.

2022 Jul;26(3):146-163. 10.21896/jksmch.2022.26.3.146.

Review and Future Perspectives of the Korea Counseling Center for Fertility and Depression Based on User Characteristics: Focusing on Those During Pregnancy and Early After Delivery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Korea Counseling Center for Fertility and Depression, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 2Incheon Regional Counselling Center for Fertility and Depression, Gachon University Gil Hospital, Incheon, Korea

- 3Daegu Regional Counselling Center for Fertility and Depression, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Korea

- 4Jeonnam Regional Counselling Center for Fertility and Depression, Hyundai Women’s & Children’s Hospital, Suncheon, Korea

- 5Gyeonggi-do Regional Counselling Center for Fertility and Depression, Korea Population, Health and Welfare Association Gyeonggi Branch, Suwon, Korea

- 6Gyeongsangbuk-do Regional Counselling Center for Fertility and Depression, Andong Medical Center, Andong, Korea

- KMID: 2532471

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2022.26.3.146

Abstract

- Purpose

This study examined the current status of counseling services provided by the Korea Counseling Center for Fertility and Depression, analyzing the characteristics of peripartum women and baby-rearing mothers and establishing guidelines for providing psychological support, and suggesting measures for improving the system.

Methods

Data on 3,660 peripartum women & their spouses and baby-rearing mothers counseled through the service over the last 4 years were collected and a demographic analysis was conducted. By analyzing the clinical information of 216 peripartum women and 219 baby-rearing mothers who have registered with the Center and received routine counseling services, factors affecting depression were identified. Finally, a paired sample t-test was conducted to verify the effect of counseling services.

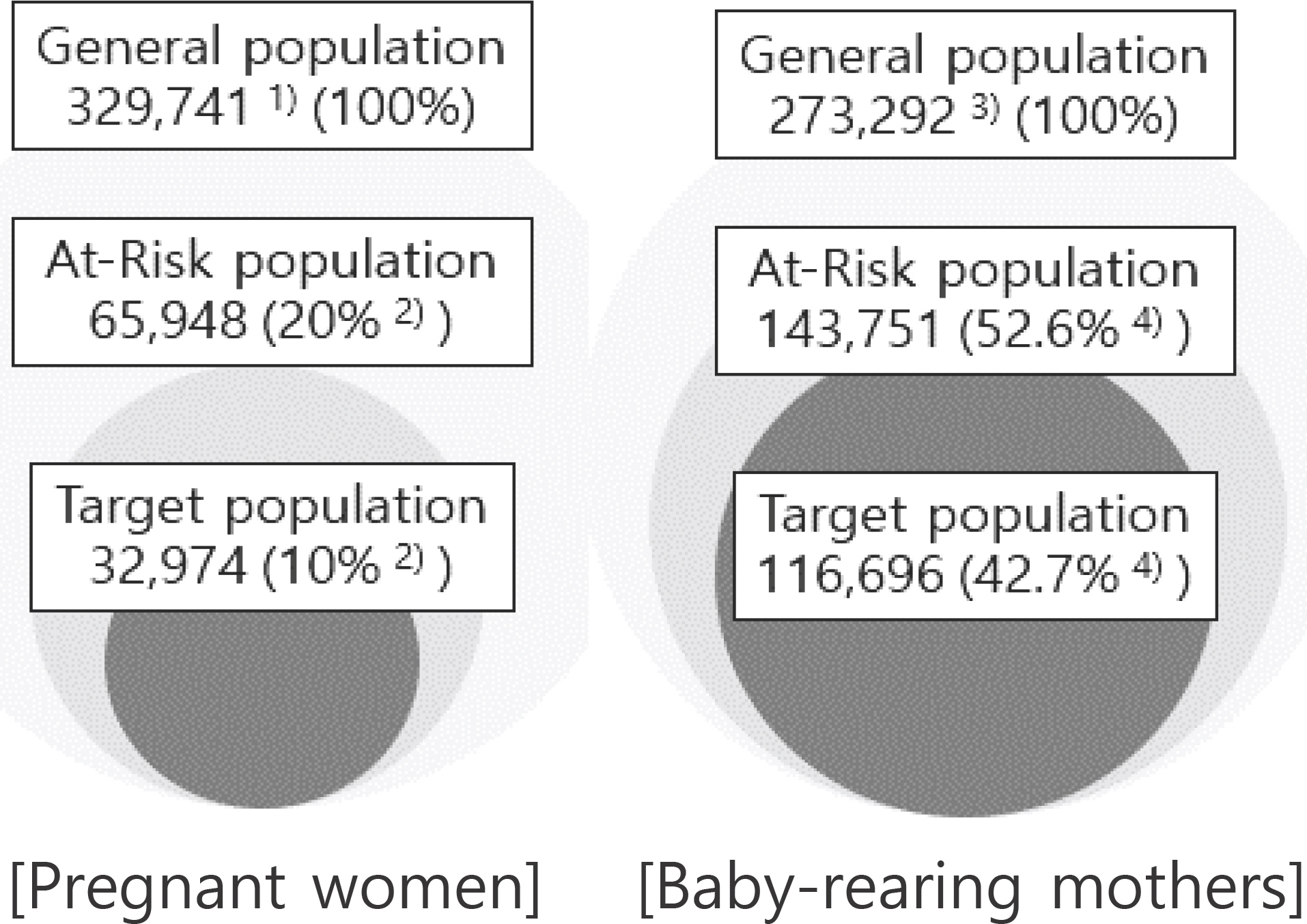

Results

An overall 20.4% of pregnant women & their spouses were screened for high risk for depression, of whom 27.3% received registered counseling services; further, 26.2% of baby-rearing parents were at high-risk group for depression, of whom 25% received registered counseling services. Results of a logistic regression analysis suggested that, for peripartum women, level of education and conflicts with partner and family were the crucial factors predicting moderate or severe depression. For baby-rearing mothers, obstetric history of spontaneous abortion was the crucial predicting factor.

Conclusion

For the early detection and prevention of peripartum depression, screening tests that start from early pregnancy should be routinely administered. Further, continuous management—covering the periods before and after childbirth—should be provided by establishing organic ties between domestic projects.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

Abdollahi F., Abhari FR., Zarghami M. Postpartum depression effect on child health and development. Acta Medica Iranica. 2017. 55:109–14.Alshikh Ahmad H., Alkhatib A., Luo J. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in the Middle East: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021. 21:542.

ArticleAmerican College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: Screening for Perinatal Depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018. 132:e208–12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders,. 5th ed.Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association;2013.Bellieni CV., Buonocore G. Abortion and subsequent mental health: review of the literature. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013. 67:301–10.

ArticleCho HJ., Choi KY., Lee JJ., Lee IS., Park MI., Na JY, et al. A study of predicting postpartum depression and the recovery factor from prepartum depression. Korean J Perinatol. 2004. 115:345–54.Chojenta CL., Lucke JC., Forder PM., Loxton DJ. Maternal health factors as risks for postnatal depression: a prospective longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2016. 19:e0147246.

ArticleChung JH. Prevalence and risk factors of pregnancy compli-cations. Cheongju (Korea): Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency;2017.Cox JL., Holden JM., Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987. 150:782–6.Crain W. Theories of development concepts and applications. 6th ed.Harlow: Pearson;2014. p. 315–30.Cranley MS. Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nurs Res. 1981. 30:281–5.

ArticleGender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. White paper on coexi-stence of men and women Reiwa 3 year edition [Internet]. Tokyo (Japan): Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office;2017. [cited 2022 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/r03/zentai/html/honpen/b2_s07_02.html.Han KE. The relationship of maternal self-esteem and maternal sensitivity with mother-to-infant attachment. Seoul (Korea): Hanyang University;2001.Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Nursing institution delivery performance [Internet]. Wonju (Korea): Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2021. [cited 2021 Dec 8]. Available from: https://www.kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=354&tblId=DT_LEE_54.Horowitz JA., Murphy CA., Gregory KE., Wojcik J. A commu-nity-based screening initiative to identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011. 40:52–61.

ArticleJun D., Johnston V., Kim JM., O'Leary S. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) in the Korean working population. Work. 2018. 59:93–102.

ArticleKei F., Tomomi K., Yoshinori M., Takafumi U., Kenji I., Tomoko K, et al. Current issues within the perinatal mental health care system in Aichi prefecture, Japan: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. 18:1–14.Kim HJ. Postpartum depression of maternities with or without occupation [dissertation]. Seoul (Korea): Ewha Womans University;2007.Kim HO. The regulating effects of parenting variables on the mother's depression and development psychological development of the infant. Korea J Child Care Educ. 2013. 83:1–21.Kim HS., Park HS., Choi A. A review on the postpartum depression management systems in Korea. J Korea Soc Matern Child Heath. 2022. 26:52–60.

ArticleKim J. Relations among maternal employment, depressive symptoms, breastfeeding duration, and body mass index trajectories in early childhood. J Korea Soc Matern Child Heath. 2020. 24:75–84.

ArticleKim J., Chu K., Lee SJ., Lee TH., Chon SJ., Cho SE, et al. Review and future perspectives of the Korea Counseling Center for Fertility and Depression (KCCFD) counseling service based on user characteristics: focusing on infertility. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2020. 24:181–95.

ArticleKim KY. Effects on maternal-infant attachment by the taegyo perspective prenatal class. Seoul (Korea): Yonsei University;2000.Kim MJ., Park JA., Sung OH., Hong SJ., Lee KS. A longitudinal cohort study of postpartum depression: mother's mental health and parent-child relationship. Korean J Infant Mental Health. 2018. 11:53–73.

ArticleKim S., Jung HY., Na KS., Lee SI., Kim SG., Lee AR, et al. A validation study of the Korean Version of Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2014. 53:237–45.

ArticleKim SR., Yun DH. Effects of social support on the mothers'psychological characteristics. Korea J Child Care Educ. 2014. 9:41–62.Kim YK., Won SD., Lim HJ., Choi SH., Lee SM., Shin YC, et al. Validation study of the Korean version of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (K-EPDS). Mood Emot. 2005. 3:42–9.Ko JY., Rockhill KM., Tong VT., Morrow B., Farr SL. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017. 66:153–8.Koh M., Ahn S., Kim J., Park S., Oh J. Pregnant women's antenatal depression and influencing factors. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2019. 25:112–23.

ArticleLee EJ., Lee JY., Lee SJ., Yu SE. Influence of self-esteem and spouse support on prenatal depression in pregnant women. J Korea Soc Matern Child Heath. 2020. 24:212–20.

ArticleLee SY., Lim JY., Hong JP. Policy implications for promoting postpartum mental health. Sejong (Korea): Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2018.Lim HJ. The differences of infant's temperament, mother's psychological characteristic, mother's parenting style as a function of types of employment status of mothers. Korean J Child Care Educ Policy. 2013. 7:190–214.Lovibond PF., Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety in-ventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995. 33:335–43.

ArticleMilgrom J., Ericksen J., Sved-Williams A. Impact of parental psychiatric illness on infant development. Sutter-Dallay AL, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NC, Guedeney A, Riecher-Rössler A, editors. Joint care of parents and infants in perinatal psychiatry. Cham: Springer;2016.

ArticleMinistry of Health and Welfare. 2021 Postpartum care survey results announcement [Internet]. Sejong (Korea): Ministry of Health and Welfare;2022. [cited 2022 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.repository.kihasa.re.kr/handle/201002/40025.Ministry of Health and Welfare. Ministry of Health and Welfare Notice 2020-147 [Internet]. Sejong (Korea). 2020. [cited 2020 Jul 13] Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb0406ls.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=030406.Korea Ministry of Government Legislation, Korean Law Information Center. Enforcement decree of the employment insurance act [Internet]. Sejong (Korea). 2022. [cited 2022 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW//lumLsLinkPop.do?lspttninfSeq=106251&chrClsCd=010202.Muller ME. A questionnaire to measure mother to infant attach. J Nurs Meas. 1994. 2:129–41.National Health Insurance Service. Application for payment of national happiness card medical expenses [Internet]. Wonju (Korea). 2021. [cited 2021 Jan 15] Available from: http://www.nhis.or.kr/nhis/policy/wbhada13900m01.do.Ogbo FA., Eastwood J., Hendry A., Jalaludin B., Agho KE., Barnett B, et al. Determinants of antenatal depression and postnatal depression in Australia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018. 18:49.

ArticlePark JH., Yoo YJ. The effect of family strengths and wives'self-esteem on depression among married women. J Korean Home Manag Assoc. 2000. 18:155–74.Park SJ., Choi HR., Choi JH., Kim KW., Hong JP. Reliability and validity of the Korean Version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood. 2010. 6:119–24.Putnick DL., Sundaram R., Bell EM., Ghassabian A., Goldstein RB., Robinson SL, et al. Trajectories of maternal postpartum depressive symptoms. Pediatrics. 2020. 146:e20200857.

ArticleSaligheh M., Rooney RM., McNamara B., Kane RT. The relationship between postnatal depression, sociodemographic factors, levels of partner support. and levels of physical activity. Front Psychol. 2014. 5:597.

ArticleShim SY. A structural analysis of the relationship among social support, maternal psychological well-being, attachment style, and young children's social-emotional competence and behavior problem. J Child Educ. 2016. 25:21–47.

ArticleSpitzer RL., Kroenke K., Wiliams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999. 282:1737–44.

ArticleStatistics Korea. 2021 Birth Statistics (provisional version) [Internet]. Daejeon (Korea): Statistics Korea;2022. [cited 2022 June 10]. Available from: http://www.kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/2/3/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=416897&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&searchInfo=&sTarget=title&sTxt=.Stuart-Parrigon K., Stuart S. Perinatal depression: an update and overview. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014. 16:468.

ArticleSzpunar MJ., Parry BL. A systematic review of cortisol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin in peripartum women with major depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018. 21:149–61.

ArticleU.S.Department of Health & Human Services. HHS launches new maternal mental health hotline [Internet]. Washington (US): U.S. Department of Health & Human Services;2022. [cited 2022 May 6]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/05/06/hhs-launches-new-maternal-mental-health-hotline.html.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn [Interent]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization;2013. [cited Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506649.Yi HY., Chung MR. The effect of maternal depressive symptoms and parenting efficacy on preschoolers'affective empathy: multi-group analysis by mother's employment status. Korean J Women Psychol. 2018. 23:91–109.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Review and Future Perspectives of the Korea Counseling Center for Fertility and Depression (KCCFD) Counseling Service Based on User Characteristics: Focusing on Infertility

- A case of Adnexal Torsion in Pregnancy

- Fertility preservation for patients with gynecologic malignancies: The Korean Society for Fertility Preservation clinical guidelines

- Reproductive counseling and pregnancy outcomes after radical trachelectomy for early stage cervical cancer

- A Clinical Study on the Postpartum Depression