Kosin Med J.

2022 Jun;37(2):140-145. 10.7180/kmj.22.104.

Incidence of arterial steno-occlusive disease and related factors in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 3Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- KMID: 2532044

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7180/kmj.22.104

Abstract

- Background

Patients who undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery receive regular physical examinations and medications on an outpatient basis. However, these patients are at risk of developing other vascular diseases, such as postoperative arterial steno-occlusive disease (SOD). This study investigated the incidence of SOD and related factors.

Methods

In total, 246 patients who underwent CABG surgery from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2021 were investigated. The incidence and risk factors of vascular disease were analyzed by dividing the included patients into SOD and non-SOD groups. Laboratory tests, medical history, surgical information, and family history were investigated through an electronic chart review.

Results

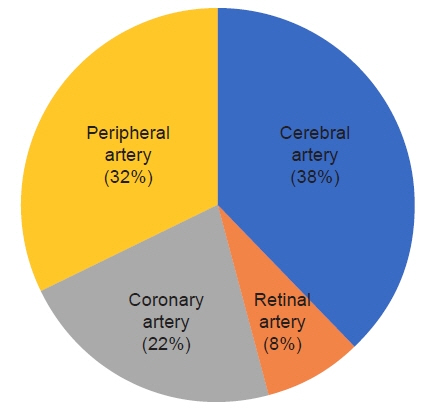

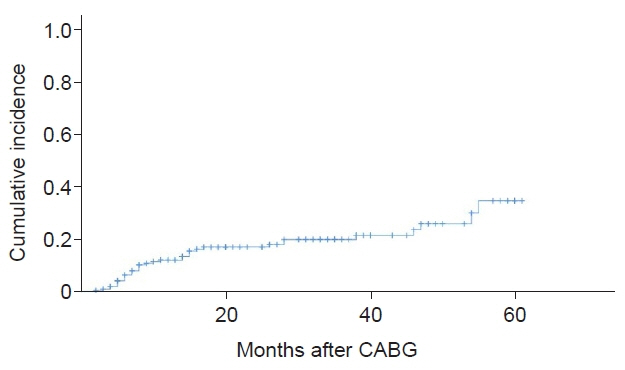

Data from 193 patients who met the criteria were analyzed. SOD occurred in 19.1% of patients, and the cerebral artery (38%) was the most common artery involved, followed by the peripheral artery (32%), the coronary artery (22%), and the retinal artery (8%). Risk factors for the development of SOD included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR; odds ratio [OR]=0.977, p=0.008), cholesterol (OR=1.020, p=0.001), and patients with diabetes complications (OR=5.077, p=0.010). The 3-year cumulative incidence rate was 21.6%, and the risk factors for cumulative occurrence were a low eGFR, elevated cholesterol, and complications of diabetes.

Conclusions

Low eGFR, high cholesterol, and the presence of diabetic complications before CABG surgery may be associated with postoperative vascular disease. In these cases, close monitoring, proper drug administration, and patient warnings may be required.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Why should you not overlook the postoperative evaluation of steno-occlusive arterial disease for coronary artery bypass graft patients?

Jong Hyun Baek, Haeyoung Lee

Kosin Med J. 2022;37(2):93-95. doi: 10.7180/kmj.22.115.

Reference

-

References

1. Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) Investigators. Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with angioplasty in patients with multivessel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:217–25.2. BARI 2D Study Group, Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, Hardison RM, Kelsey SF, et al. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:2503–15.

Article3. King SB 3rd, Lembo NJ, Weintraub WS, Kosinski AS, Barnhart HX, Kutner MH, et al. A randomized trial comparing coronary angioplasty with coronary bypass surgery. Emory Angioplasty versus Surgery Trial (EAST). N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:1044–50.

Article4. Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:961–72.

Article5. Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, Siami FS, Dangas G, Mack M, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:2375–84.

Article6. Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005; 111:3481–8.

Article7. Saadoun D, Vautier M, Cacoub P. Medium- and large-vessel vasculitis. Circulation. 2021; 143:267–82.

Article8. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's disease). N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:864–9.

Article9. Gornik HL, Persu A, Adlam D, Aparicio LS, Azizi M, Boulanger M, et al. First International Consensus on the diagnosis and management of fibromuscular dysplasia. Vasc Med. 2019; 24:164–89.

Article10. Anogeianaki A, Angelucci D, Cianchetti E, D'Alessandro M, Maccauro G, Saggini A, et al. Atherosclerosis: a classic inflammatory disease. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011; 24:817–25.

Article11. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1685–95.

Article12. Wanamaker KM, Moraca RJ, Nitzberg D, Magovern GJ Jr. Contemporary incidence and risk factors for carotid artery disease in patients referred for coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012; 7:78.

Article13. Huang CH, Hsu CP, Lai ST, Weng ZC, Tsao NW, Tsai TH. Operative results of coronary artery bypass grafting in women. Int J Cardiol. 2004; 94:61–6.

Article14. Drohomirecka A, Koltowski L, Kwinecki P, Wronecki K, Cichon R. Risk factors for carotid artery disease in patients scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting. Kardiol Pol. 2010; 68:789–94.15. Venkatachalam S, Gray BH, Mukherjee D, Shishehbor MH. Contemporary management of concomitant carotid and coronary artery disease. Heart. 2011; 97:175–80.

Article16. Resch JA, Baker AB. Etiologic mechanisms in cerebral atherosclerosis: preliminary study of 3,839 cases. Arch Neurol. 1964; 10:617–28.17. Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Zamanillo MC. Race-ethnic differences in stroke risk factors among hospitalized patients with cerebral infarction: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology. 1995; 45:659–63.

Article18. Ingall TJ, Homer D, Baker HL Jr, Kottke BA, O'Fallon WM, Whisnant JP. Predictors of intracranial carotid artery atherosclerosis: duration of cigarette smoking and hypertension are more powerful than serum lipid levels. Arch Neurol. 1991; 48:687–91.

Article19. Rincon F, Sacco RL, Kranwinkel G, Xu Q, Paik MC, Boden-Albala B, et al. Incidence and risk factors of intracranial atherosclerotic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009; 28:65–71.

Article20. Allison MA, Criqui MH, McClelland RL, Scott JM, McDermott MM, Liu K, et al. The effect of novel cardiovascular risk factors on the ethnic-specific odds for peripheral arterial disease in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:1190–7.

Article21. Murabito JM, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Wilson WF. Intermittent claudication: a risk profile from the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1997; 96:44–9.22. Lu Y, Ballew SH, Tanaka H, Szklo M, Heiss G, Coresh J, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure classification and incident peripheral artery disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020; 27:51–9.

Article23. McLean RC, Nazarian SM, Gluckman TJ, Schulman SP, Thiemann DR, Shapiro EP, et al. Relative importance of patient, procedural and anatomic risk factors for early vein graft thrombosis after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2011; 52:877–85.24. Zhang L, Wu JH, Otto JC, Gurley SB, Hauser ER, Shenoy SK, et al. Interleukin-9 mediates chronic kidney disease-dependent vein graft disease: a role for mast cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2017; 113:1551–9.

Article25. Wellenius GA, Mukamal KJ, Winkelmayer WC, Mittleman MA. Renal dysfunction increases the risk of saphenous vein graft occlusion: results from the post-CABG trial. Atherosclerosis. 2007; 193:414–20.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Intractable Coronary Spasm Requiring Percutaneous Coronary Intervention after Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in a Patient with Moyamoya Disease

- Endovascular Management for Chronic Steno-occlusion of Iliac and Femoral Arteries

- The Right Gastroepiploic Artery Graft for Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: A 30-Year Experience

- The accidental renal artery embolism in patient with aortoiliac occlusive disease with unilateral renal atrophy during aortobifemoral bypass graft: A case report

- Why should you not overlook the postoperative evaluation of steno-occlusive arterial disease for coronary artery bypass graft patients?