J Korean Med Sci.

2022 May;37(17):e129. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e129.

Mediating Effect of Viral Anxiety and Perceived Benefits of Physical Distancing on Adherence to Distancing Among High School Students Amid COVID-19

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

- 3Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Meram School of Medicine, Necmettin Erbakan University, Konya, Turkey

- KMID: 2529701

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e129

Abstract

- Background

The aim of this study is to explore whether high school students’ adherence to physical distancing was associated with health beliefs, social norms, and psychological factors during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

Overall, 300 high school students participated in this anonymous online survey conducted from October 18–24, 2021. The survey included rating scales such as attitude toward physical distancing during the pandemic, Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 items (SAVE-6), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items, Satisfaction with Life Scale, and Connor Davidson Resilience Scale 2-items.

Results

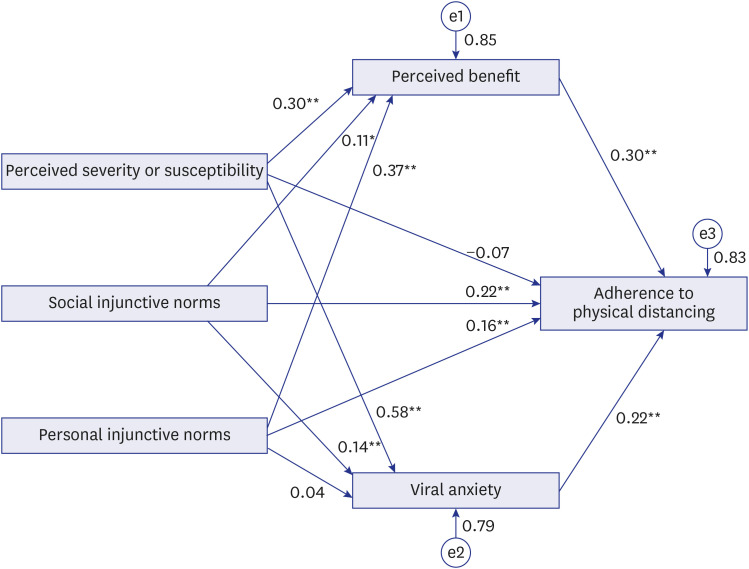

The results revealed that perceived susceptibility or severity (β = −0.13, P = 0.038), perceived benefit (β = 0.32, P < 0.001), descriptive social norms (β = 0.10, P = 0.041), social injunctive norms (β = 0.19, P < 0.001), and SAVE-6 (β = 0.24, P < 0.001) predicted students’ adherence to physical distancing (adjusted R 2 = 0.42, F = 19.2, P < 0.001). Social injunctive norms and personal injunctive norms directly influenced adherence to physical distancing. Viral anxiety, measured by SAVE-6, mediated the association between social injunctive norms and adherence to physical distancing, and perceived benefits mediated the relationship between personal injunctive norms and adherence to physical distancing. The influence of perceived susceptibility or severity on adherence to physical distancing was entirely mediated by perceived benefits or viral anxiety.

Conclusion

Explaining the rationale or benefits of physical distancing may be important in increasing adherence to physical distancing among high school students.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Buselli R, Corsi M, Baldanzi S, Chiumiento M, Del Lupo E, Dell’Oste V, et al. Professional quality of life and mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6180.2. Shahrabani S, Benzion U, Yom Din G. Factors affecting nurses’ decision to get the flu vaccine. HEPAC Health Econ Prev Care. 2009; 10(2):227–231.3. Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, Amit S, Lipsitch M, Cohen C, et al. Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385(16):1474–1484. PMID: 34320281.4. Girum T, Lentiro K, Geremew M, Migora B, Shewamare S, Shimbre MS. Optimal strategies for COVID-19 prevention from global evidence achieved through social distancing, stay at home, travel restriction and lockdown: a systematic review. Arch Public Health. 2021; 79(1):150. PMID: 34419145.5. Liu H, Chen C, Cruz-Cano R, Guida JL, Lee M. Public Compliance with social distancing measures and SARS-CoV-2 spread: a quantitative analysis of 5 states. Public Health Rep. 2021; 136(4):475–482. PMID: 33909541.6. Wasserman D, van der Gaag R, Wise J. The term “physical distancing” is recommended rather than “social distancing” during the COVID-19 pandemic for reducing feelings of rejection among people with mental health problems. Eur Psychiatry. 2020; 63(1):e52. PMID: 32475365.7. Weill JA, Stigler M, Deschenes O, Springborn MR. Social distancing responses to COVID-19 emergency declarations strongly differentiated by income. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117(33):19658–19660. PMID: 32727905.8. Soltanian AR, Omidi T, Khazaei S, Bashirian S, Heidarimoghadam R, Jenabi E, et al. Assessment of mask-wearing adherence and social distancing compliance in public places in Hamadan, Iran, during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Health Sci. 2021; 21(3):e00526. PMID: 34698660.9. Zang E, West J, Kim N, Pao C. U.S. regional differences in physical distancing: Evaluating racial and socioeconomic divides during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021; 16(11):e0259665. PMID: 34847174.10. Tong KK, Chen JH, Yu EW, Wu AM. Adherence to COVID-19 precautionary measures: applying the health belief model and generalised social beliefs to a probability community sample. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2020; 12(4):1205–1223. PMID: 33010119.11. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model: Explaining health behavior through expectancies. Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. The Jossey-Bass Health Series. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Jossey-Bass/Wiley;1990. p. 39–62.12. Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007; 26(2):136–145. PMID: 17385964.13. Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ. Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004; 55(1):591–621. PMID: 14744228.14. Rivis A, Sheeran P. Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Curr Psychol. 2003; 22(3):218–233.15. Manstead ASR. The role of moral norm in the attitude–behavior relation. Terry DJ, Hogg MA, editors. Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Context: The Role of Norms and Group Membership. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;1999. p. 11–30.16. Byun S, Slavin RE. Educational responses to the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. Best Evid Chin Edu. 2020; 5(2):665–680.17. Thakur A. Mental health in high school students at the time of COVID-19: a student’s perspective. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020; 59(12):1309–1310. PMID: 32860905.18. Igra V, Irwin CE Jr. Theories of adolescent risk-taking behavior. DiClemente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. Cleveland, OH, USA: Plenum Press;1996. p. 35–51.19. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004; 6(3):e34. PMID: 15471760.20. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;1988.21. Gouin JP, MacNeil S, Switzer A, Carrese-Chacra E, Durif F, Knäuper B. Socio-demographic, social, cognitive, and emotional correlates of adherence to physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Can J Public Health. 2021; 112(1):17–28. PMID: 33464556.22. Chung S, Ahn MH, Lee S, Kang S, Suh S, Shin YW. The Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 Items (SAVE-6) scale: a new instrument for assessing the anxiety response of general population to the viral epidemic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:669606. PMID: 34149565.23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID: 11556941.24. Park SJ, Choi HR, Choi JH, Kim K, Hong JP. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood. 2010; 6(2):119–124.25. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985; 49(1):71–75. PMID: 16367493.26. Jeong HS, Kang I, Namgung E, Im JJ, Jeon Y, Son J, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-2 in firefighters and rescue workers. Compr Psychiatry. 2015; 59:123–128. PMID: 25744698.27. Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press;2006.28. Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates;2001.29. Hounton SH, Carabin H, Henderson NJ. Towards an understanding of barriers to condom use in rural Benin using the Health Belief Model: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2005; 5(1):8. PMID: 15663784.30. Alberts A, Elkind D, Ginsberg S. The personal fable and risk-taking in early adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2007; 36(1):71–76.31. Schultz PW, Nolan JM, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, Griskevicius V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol Sci. 2007; 18(5):429–434. PMID: 17576283.32. Shapiro JP, Baumeister RF, Kessler JW. A three-component model of children’s teasing: Aggression, humor, and ambiguity. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1991; 10(4):459–472.33. Krekel C, Swanke S, De Neve JE, Fancourt D. IZA DP No. 13690. Are Happier People More Compliant? Global Evidence from Three Large-Scale Surveys during COVID-19 Lockdowns. Bonn, Germany: IZA Institute of Labor Economics;2020.34. Stickley A, Matsubayashi T, Sueki H, Ueda M. COVID-19 preventive behaviours among people with anxiety and depressive symptoms: findings from Japan. Public Health. 2020; 189:91–93. PMID: 33189941.35. Wright L, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Predictors of self-reported adherence to COVID-19 guidelines. A longitudinal observational study of 51,600 UK adults. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021; 4:100061. PMID: 33997831.36. Seo YM, Choi WH. COVID-19 prevention behavior and its affecting factors in high school students. Korean J Health Serv Manag. 2020; 14(4):215–225.37. Ryan RG. Age differences in personality: adolescents and young adults. Pers Individ Dif. 2009; 47(4):331–335.38. Kelley AE, Schochet T, Landry CF. Risk taking and novelty seeking in adolescence: introduction to part I. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004; 1021(1):27–32. PMID: 15251871.39. World Health Organization. Pandemic Fatigue: Reinvigorating the Public to Prevent COVID-19: Policy Framework for Supporting Pandemic Prevention and Management: Revised Version November 2020. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe;2020.40. Acquah EO, Wilson ML, Doku DT. Patterns and correlates for bullying among young adolescents in Ghana. Soc Sci. 2014; 3(4):827–840.41. Bastiaensens S, Pabian S, Vandebosch H, Poels K, Van Cleemput K, DeSmet A, et al. From normative influence to social pressure: how relevant others affect whether bystanders join in cyberbullying. Soc Dev. 2016; 25(1):193–211.42. Chung S, Kim HJ, Ahn MH, Yeo S, Lee J, Kim K, et al. Development of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) Scale for assessing work-related stress and anxiety in healthcare workers in response to viral epidemics. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(47):e319. PMID: 34873885.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Influence of Physical Distancing, Sense of Belonging, and Resilience of Nursing Students on Their Viral Anxiety During the COVID-19 Era

- Adherence to Physical Distancing and Health Beliefs About COVID-19 Among Patients With Cancer

- A Comparison of the Perception of and Adherence to the COVID-19 Social Distancing Behavior Guidelines among Health Care Workers, Patients, and General Public

- Influence of Intolerance of Uncertainty on Preoccupation With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Among Frontline Nursing Professionals: Mediating Role of Reassurance-Seeking Behavior and Adherence to Physical Distancing

- Psychosocial changes in Medical Students Before and After COVID-19 Social Distancing