J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Apr;37(16):e126. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e126.

Changes in Anxiety Level and Personal Protective Equipment Use Among Healthcare Workers Exposed to COVID-19

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang University, Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2529293

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e126

Abstract

- Background

The relationship between changes in anxiety levels and personal protective equipment (PPE) use is yet to be evaluated. The present study assessed this relationship among healthcare workers (HCWs) involved in the care of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

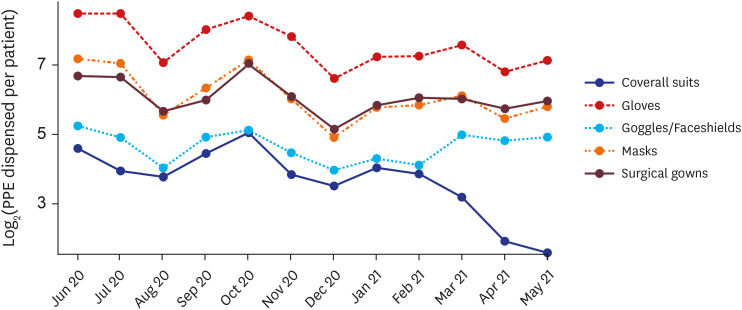

An online survey was conducted in a municipal hospital with 195 nationally designated negative pressure isolation units in Korea. Anxiety level was measured using the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), and changes in anxiety levels were assessed based on the time when COVID-19 vaccine was introduced in March 2021 in Korea. Monthly PPE usage between June 2020 and May 2021 was investigated.

Results

The mean SAS score (33.25 ± 5.97) was within normal range and was lower than those reported in previous studies conducted before COVID-19 vaccination became available. Among the 93 HCWs who participated, 64 (68.8%) answered that their fear of contracting COVID-19 decreased after vaccination. The number of coveralls used per patient decreased from 33.6 to 0. However, a demand for more PPE than necessary was observed in situations where HCWs were exposed to body fluids and secretions (n = 38, 40.9%). Excessive demand for PPE was not related to age, working experience, or SAS score.

Conclusion

Anxiety in HCWs exposed to COVID-19 was lower than it was during the early period of the pandemic, and the period before vaccination was introduced. The number of coveralls used per patient also decreased although an excessive demand for PPE was observed.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Effect of Wearing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for COVID-19 Treatment on Blood Culture Contamination: Implication for Optimal PPE Strategies

Jae Hyeon Park, Taek Soo Kim, Chan Mi Lee, Chang Kyung Kang, Wan Beom Park, Nam Joong Kim, Pyoeng Gyun Choe, Myoung-don Oh

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(23):e180. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e180.

Reference

-

1. Tao K, Tzou PL, Nouhin J, Gupta RK, de Oliveira T, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Rev Genet. 2021; 22(12):757–773. PMID: 34535792.2. World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Updated 2020. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/info .3. Kang E, Lee SY, Kim MS, Jung H, Kim KH, Kim KN, et al. The physiological burden of COVID-19 stigma: evaluation of the mental health of isolated mild condition COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2021; 36(3):1–13.4. Choi I, Kim JH, Kim N, Choi E, Choi J, Suk HW, et al. How COVID-19 affected mental well-being: an 11- week trajectories of daily well-being of Koreans amidst COVID-19 by age, gender and region. PLoS One. 2021; 16(4):e0250252. PMID: 33891642.5. Shreffler J, Petrey J, Huecker M. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: a scoping review. West J Emerg Med. 2020; 21(5):1059–1066. PMID: 32970555.6. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004; 170(5):793–798. PMID: 14993174.7. Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clin Med Res. 2016; 14(1):7–14. PMID: 26847480.8. Mo Y, Deng L, Zhang L, Lang Q, Liao C, Wang N, et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag. 2020; 28(5):1002–1009. PMID: 32255222.9. Park C, Hwang JM, Jo S, Bae SJ, Sakong J. COVID-19 outbreak and its association with healthcare workers’ emotional stress: a cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(41):e372. PMID: 33107230.10. Savoia E, Argentini G, Gori D, Neri E, Piltch-Loeb R, Fantini MP. Factors associated with access and use of PPE during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study of Italian physicians. PLoS One. 2020; 15(10):e0239024. PMID: 33044978.11. Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020; 324(8):782–793. PMID: 32648899.12. Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). IPAC recommendations for use of personal protective equipment for care of individuals with suspect or confirmed COVID-19 (6th revision). Updated 2021. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/ .13. Zhang SX, Liu J, Afshar Jahanshahi A, Nawaser K, Yousefi A, Li J, et al. At the height of the storm: healthcare staff’s health conditions and job satisfaction and their associated predictors during the epidemic peak of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87(1):144–146. PMID: 32387345.14. Delgado D, Wyss Quintana F, Perez G, Sosa Liprandi A, Ponte-Negretti C, Mendoza I, et al. Personal safety during the COVID-19 pandemic: realities and perspectives of healthcare workers in Latin America. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(8):2798.15. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971; 12(6):371–379. PMID: 5172928.16. Lee JH. Development of the Korean form of Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 1996; 13(2):279–294.17. Unoki T, Tamoto M, Ouchi A, Sakuramoto H, Nakayama A, Katayama Y, et al. Personal protective equipment use by healthcare workers in Intensive Care Unit during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: Comparative analysis with the PPE-SAFE survey. Acute Med Surg. 2020; 7(1):e584.18. Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages - the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(18):e41. PMID: 32212516.19. World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages. Updated 2020. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/rational-use-of-personal-protective-equipment-for-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-and-considerations-during-severe-shortages .20. Bohlken J, Schömig F, Lemke MR, Pumberger M, Riedel-Heller SG. COVID-19 pandemic: stress experience of healthcare workers - a short current review. Psychiatr Prax. 2020; 47(4):190–197. PMID: 32340048.21. Centers for Disease control and Prevention. Interim guidance for managing healthcare personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection or exposure to SARS-Cov-2. Updated 2022. Accessed July 31, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html .22. Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Ren AK, Zhou XP. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2020; 38(3):192–195. PMID: 32131151.23. Jijun W, Xian S, Fei C, Yuanjie D, Dechun C, Xingcao J, et al. Investigation on sleep quality of first line nurses in fighting against novel coronavirus pneumonia and its influencing factors. Nurs Res China. 2020; 34(7):558–562.24. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020; 26:e923549. PMID: 32132521.25. Wenhui Z, Er L, Yi Z. Investigation and countermeasures of anxiety of nurses in a designated hospital of novel coronavirus pneumonia in Hangzhou. Health Res. 2020; 40:130–133.26. Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, Xu X, Dou QL, Zhang WW, et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020; 148:e98. PMID: 32430088.27. Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020; 323(21):2133–2134. PMID: 32259193.28. Delaney RK, Locke A, Pershing ML, Geist C, Clouse E, Precourt Debbink M, et al. Experiences of a health system’s faculty, staff, and trainees’ career development, work culture, and childcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(4):e213997. PMID: 33797552.29. Pan R, Zhang L, Pan J. The anxiety status of Chinese medical workers during the epidemic of COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2020; 17(5):475–480.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic

- Personal Protective Equipment for Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Assessment and Management of Dysphagia during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Hospital Infection Control Practice in the COVID-19 Era: An Experience of University Affiliated Hospital

- The experience of infection prevention for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during general anesthesia in an epidemic of COVID-19: including unexpected exposure case - Two cases report -