J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Feb;37(7):e54. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e54.

Clinical Differences Between Stroke and Stroke Mimics in Code Stroke Patients

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Keimyung University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- 2Department of Neurology, Emergency Medical Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2526517

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e54

Abstract

- Background

The code stroke system is designed to identify stroke patients who may benefit from reperfusion therapy. It is essential for emergency physicians to rapidly distinguish true strokes from stroke mimics to activate code stroke. This study aimed to investigate the clinical and neurological characteristics that can be used to differentiate between stroke and stroke mimics in the emergency department (ED).

Methods

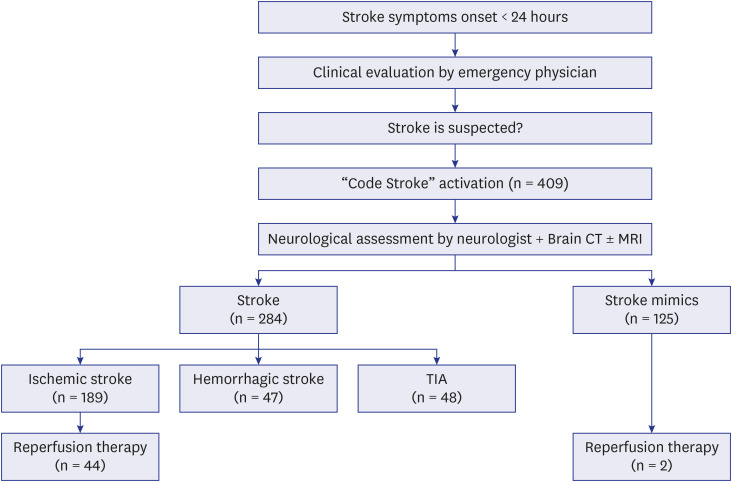

We conducted a retrospective observational study of code stroke patients in the ED from January to December 2019. The baseline characteristics and the clinical and neurological features of stroke mimics were compared with those of strokes.

Results

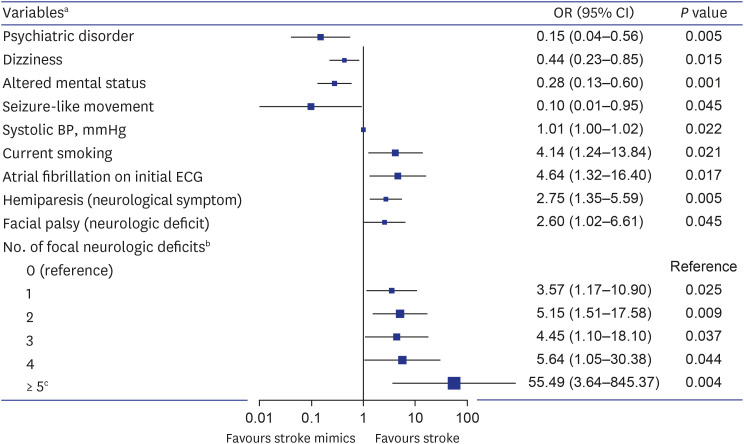

A total of 409 code stroke patients presented to the ED, and 125 (31%) were diagnosed with stroke mimics. The common stroke mimics were seizures (21.7%), drug toxicity (12.0%), metabolic disorders (11.2%), brain tumors (8.8%), and peripheral vertigo (7.2%). The independent predictors of stroke mimics were psychiatric disorders, dizziness, altered mental status, and seizure-like movements, while current smoking, elevated systolic blood pressure, atrial fibrillation on the initial electrocardiogram, hemiparesis as a symptom, and facial palsy as a sign suggested a stroke. In addition, the likelihood of a stroke in code stroke patients tended to increase as the number of accompanying deficits increased from the following set of seven focal neurological deficits: hemiparesis (or upper limb monoparesis), unilateral limb sensory change, facial palsy, dysarthria, aphasia (or neglect), visual field defect, and oculomotor disorder (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Some clinical and neurological characteristics have been identified to help differentiate stroke mimics from true stroke. In particular, the likelihood of stroke tended to increase as the number of accompanying focal neurological deficits increased.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kim JY, Kang K, Kang J, Koo J, Kim DH, Kim BJ, et al. Executive summary of stroke statistics in Korea 2018: a report from the epidemiology research council of the Korean Stroke Society. J Stroke. 2019; 21(1):42–59. PMID: 30558400.

Article2. Hand PJ, Kwan J, Lindley RI, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Distinguishing between stroke and mimic at the bedside: the brain attack study. Stroke. 2006; 37(3):769–775. PMID: 16484610.

Article3. Merino JG, Luby M, Benson RT, Davis LA, Hsia AW, Latour LL, et al. Predictors of acute stroke mimics in 8187 patients referred to a stroke service. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013; 22(8):e397–e403. PMID: 23680681.

Article4. Magauran BG Jr, Nitka M. Stroke mimics. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2012; 30(3):795–804. PMID: 22974649.

Article5. Kim MC, Kim SW. Improper use of thrombolytic agents in acute hemiparesis following misdiagnosis of acute ischemic stroke. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2018; 14(1):20–23. PMID: 29774194.

Article6. Kim SJ, Kim DW, Kim HY, Roh HG, Park JJ. Seizure in code stroke: stroke mimic and initial manifestation of stroke. Am J Emerg Med. 2019; 37(10):1871–1875. PMID: 30598373.

Article7. Tsivgoulis G, Zand R, Katsanos AH, Goyal N, Uchino K, Chang J, et al. Safety of intravenous thrombolysis in stroke mimics: prospective 5-year study and comprehensive meta-analysis. Stroke. 2015; 46(5):1281–1287. PMID: 25791717.

Article8. Kim JT, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Reeves MJ, Navalkele DD, Grotta JC, et al. Treatment with tissue plasminogen activator in the golden hour and the shape of the 4.5-hour time-benefit curve in the national United States Get With The Guidelines-Stroke population. Circulation. 2017; 135(2):128–139. PMID: 27815374.

Article9. Vilela P. Acute stroke differential diagnosis: Stroke mimics. Eur J Radiol. 2017; 96:133–144. PMID: 28551302.

Article10. Liberman AL, Prabhakaran S. Stroke chameleons and stroke mimics in the emergency department. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017; 17(2):15. PMID: 28229398.

Article11. Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical mimics: an emergency medicine-focused review of stroke mimics. J Emerg Med. 2017; 52(2):176–183. PMID: 27780653.

Article12. Nguyen PL, Chang JJ. Stroke mimics and acute stroke evaluation: clinical differentiation and complications after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. J Emerg Med. 2015; 49(2):244–252. PMID: 25802155.

Article13. Yahia MM, Bashir SJ. Clinical characteristics of stroke mimics presenting to a stroke center within the therapeutic window of thrombolysis. Brain Neurorehabil. 2018; 11(1):e9.

Article14. Nor AM, Davis J, Sen B, Shipsey D, Louw SJ, Dyker AG, et al. The Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) scale: development and validation of a stroke recognition instrument. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4(11):727–734. PMID: 16239179.

Article15. Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, Christensen S, Tsai JP, Ortega-Gutierrez S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378(8):708–718. PMID: 29364767.

Article16. Ko SB, Park HK, Kim BM, Heo JH, Rha JH, Kwon SU, et al. 2019 update of the Korean clinical practice guidelines of stroke for endovascular recanalization therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Neurointervention. 2019; 14(2):71–81. PMID: 31437873.

Article17. El Husseini N, Goldstein LB. “Code stroke”: hospitalized versus emergency department patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013; 22(4):345–348. PMID: 22206693.

Article18. Chan PH, Lau CP, Tse HF, Chiang CE, Siu CW. CHA2DS2-VASc recalibration with an additional age category (50-64 years) enhances stroke risk stratification in chinese patients with atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2016; 32(12):1381–1387. PMID: 27523274.

Article19. Vroomen PC, Buddingh MK, Luijckx GJ, De Keyser J. The incidence of stroke mimics among stroke department admissions in relation to age group. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008; 17(6):418–422. PMID: 18984438.

Article20. Goyal N, Tsivgoulis G, Male S, Metter EJ, Iftikhar S, Kerro A, et al. FABS: an intuitive tool for screening of stroke mimics in the emergency department. Stroke. 2016; 47(9):2216–2220. PMID: 27491733.21. Bustamante A, López-Cancio E, Pich S, Penalba A, Giralt D, García-Berrocoso T, et al. Blood biomarkers for the early diagnosis of stroke: the stroke-chip study. Stroke. 2017; 48(9):2419–2425. PMID: 28716979.22. Sacco RL, Benjamin EJ, Broderick JP, Dyken M, Easton JD, Feinberg WM, et al. Risk factors. Stroke. 1997; 28(7):1507–1517. PMID: 9227708.

Article23. Hong KS, Bang OY, Kang DW, Yu KH, Bae HJ, Lee JS, et al. Stroke statistics in Korea: part I. Epidemiology and risk factors: a report from the Korean stroke society and clinical research center for stroke. J Stroke. 2013; 15(1):2–20. PMID: 24324935.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pneumococcal meningitis complicated by otomastoiditis and pneumocephalus confounding an acute ischemic stroke diagnosis

- Rate of Stroke Mimics over Telestroke

- Journal of Stroke (JoS) Receives High Impact Factor

- Resurrection of Endovascular Thrombectomy for Posterior Circulation Stroke

- Differences in Effectiveness among Devices for Endovascular Thrombectomy in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke